Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (UK: /mætˈsiːni/,[4] US: /mɑːtˈ-, mɑːdˈziːni/,[5][6] Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe matˈtsiːni]; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, activist for the unification of Italy, and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the independent and unified Italy[7] in place of the several separate states, many dominated by foreign powers, that existed until the 19th century. He also helped define the modern European movement for popular democracy in a republican state.[8]

Giuseppe Mazzini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Triumvir of the Roman Republic | |

| In office 5 February 1849 – 3 July 1849 | |

| Preceded by | Aurelio Saliceti |

| Succeeded by | Aurelio Saliceti |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 June 1807 Genoa, Gênes, French Empire |

| Died | 10 March 1872 (aged 66) Pisa, Italy |

| Political party | Young Italy (1831–48) Action Party (1848–67) |

| Alma mater | University of Genoa |

| Profession |

|

Philosophy career | |

| Era | 19th-century |

| School | Romanticism Providentialism |

Main interests | History, theology, politics |

Notable ideas | Pan-Europeanism, irridentism, popular democracy, class collaboration |

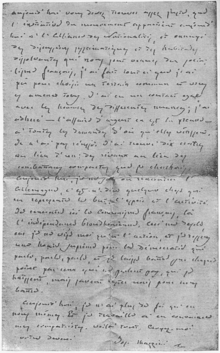

| Signature | |

Mazzini's thoughts had a very considerable influence on the Italian and European republican movements, in the Constitution of Italy, about Europeanism, and, more nuanced, on many politicians of a later period: among them, men like U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, but also post-colonial leaders such as Gandhi, Savarkar, Golda Meir, David Ben-Gurion, Kwame Nkrumah, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sun Yat-sen.[9]

Biography

Early years

Mazzini was born in Genoa, then part of the Ligurian Republic, under the rule of the French Empire. His father, Giacomo Mazzini, originally from Chiavari, was a university professor who had adhered to Jacobin ideology; his mother, Maria Drago, was renowned for her beauty and religious (Jansenist) fervour. From a very early age, Mazzini showed good learning qualities (as well as a precocious interest in politics and literature). He was admitted to university at 14, graduating in law in 1826, and initially practiced as a "poor man's lawyer". Mazzini also hoped to become a historical novelist or a dramatist, and in the same year wrote his first essay, Dell'amor patrio di Dante ("On Dante's Patriotic Love"), published in 1827. In 1828–29 he collaborated with a Genoese newspaper, L'Indicatore Genovese, which was however soon closed by the Piedmontese authorities. He then became one of the leading authors of L'Indicatore Livornese, published at Livorno by F. D. Guerrazzi, until this paper was closed down by the authorities, too.

In 1827 Mazzini travelled to Tuscany, where he became a member of the Carbonari, a secret association with political purposes. On 31 October of that year he was arrested at Genoa and interned at Savona. In early 1831, he was released from prison, but confined to a small hamlet. He chose exile instead, moving to Geneva in Switzerland.

Failed insurrections

In 1831 Mazzini went to Marseille, where he became a popular figure among the Italian exiles. He was a frequent visitor to the apartment of Giuditta Bellerio Sidoli, a beautiful Modenese widow who became his lover.[10] In August 1832 Giuditta Sidoli gave birth to a boy, almost certainly Mazzini's son, whom she named Joseph Démosthène Adolpe Aristide after members of the family of Démosthène Ollivier, with whom Mazzini was staying. The Olliviers took care of the child in June 1833 when Giuditta and Mazzini left for Switzerland. The child died in February 1835.[11]

Mazzini organized a new political society called Young Italy. Young Italy was a secret society formed to promote Italian unification: "One, free, independent, republican nation."[12] Mazzini believed that a popular uprising would create a unified Italy, and would touch off a European-wide revolutionary movement.[10] The group's motto was God and the People,[13] and its basic principle was the unification of the several states and kingdoms of the peninsula into a single republic as the only true foundation of Italian liberty. The new nation had to be: "One, Independent, Free Republic".

Mazzini's political activism met some success in Tuscany, Abruzzi, Sicily, Piedmont, and his native Liguria, especially among several military officers. Young Italy counted about 60,000 adherents in 1833, with branches in Genoa and other cities. In that year Mazzini first attempted insurrection, which would spread from Chambéry (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), Alessandria, Turin, and Genoa. However, the Savoy government discovered the plot before it could begin and many revolutionaries (including Vincenzo Gioberti) were arrested. The repression was ruthless: 12 participants were executed, while Mazzini's best friend and director of the Genoese section of the Giovine Italia, Jacopo Ruffini, killed himself. Mazzini was tried in absentia and sentenced to death.

Despite this setback (whose victims later created numerous doubts and psychological strife in Mazzini), he organized another uprising for the following year. A group of Italian exiles were to enter Piedmont from Switzerland and spread the revolution there, while Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had recently joined Young Italy, was to do the same from Genoa. However, the Piedmontese troops easily crushed the new attempt.

In the spring of 1834, while at Bern, Mazzini and a dozen refugees from Italy, Poland, and Germany founded a new association with the grandiose name of Young Europe. Its basic, and equally grandiose idea, was that, as the French Revolution of 1789 had enlarged the concept of individual liberty, another revolution would now be needed for national liberty; and his vision went further because he hoped that in the no doubt distant future free nations might combine to form a loosely federal Europe with some kind of federal assembly to regulate their common interests. [...] His intention was nothing less than to overturn the European settlement agreed in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, which had reestablished an oppressive hegemony of a few great powers and blocked the emergence of smaller nations. [...] Mazzini hoped, but without much confidence, that his vision of a league or society of independent nations would be realized in his own lifetime. In practice Young Europe lacked the money and popular support for more than a short-term existence. Nevertheless he always remained faithful to the ideal of a united continent for which the creation of individual nations would be an indispensable preliminary.[14]

On 28 May 1834 Mazzini was arrested at Solothurn, and exiled from Switzerland. He moved to Paris, where he was again imprisoned on 5 July. He was released only after promising he would move to England. Mazzini, together with a few Italian friends, moved in January 1837 to live in London in very poor economic conditions.

Exile in London

_-_Giuseppe_Mazzini.jpg)

On 30 April 1840 Mazzini reformed the Giovine Italia in London, and on 10 November of the same year he began issuing the Apostolato popolare ("Apostleship of the People").

A succession of failed attempts at promoting further uprisings in Sicily, Abruzzi, Tuscany, and Lombardy-Venetia discouraged Mazzini for a long period, which dragged on until 1840. He was also abandoned by Sidoli, who had returned to Italy to rejoin her children. The help of his mother pushed Mazzini to create several organizations aimed at the unification or liberation of other nations, in the wake of Giovine Italia:[15] "Young Germany", "Young Poland", and "Young Switzerland", which were under the aegis of "Young Europe" (Giovine Europa). He also created an Italian school for poor people active from 10 November 1841 at 5 Greville Street, London.[16] From London he also wrote an endless series of letters to his agents in Europe and South America, and made friends with Thomas Carlyle and his wife Jane. The "Young Europe" movement also inspired a group of young Turkish army cadets and students who, later in history, named themselves the "Young Turks".

In 1843 he organized another riot in Bologna, which attracted the attention of two young officers of the Austrian Navy, Attilio and Emilio Bandiera. With Mazzini's support, they landed near Cosenza (Kingdom of Naples), but were arrested and executed. Mazzini accused the British government of having passed information about the expeditions to the Neapolitans, and question was raised in the British Parliament. When it was admitted[17] that his private letters had indeed been opened, and its contents revealed by the Foreign Office[18] to the Austrian[19] and Neapolitan governments, Mazzini gained popularity and support among the British liberals, who were outraged by such a blatant intrusion of the government into his private correspondence.[16]

In 1847 he moved again to London, where he wrote a long "open letter" to Pope Pius IX, whose apparently liberal reforms had gained him a momentary status as possible paladin of the unification of Italy. The Pope, however, did not reply. He also founded the People's International League. By 8 March 1848 Mazzini was in Paris, where he launched a new political association, the Associazione Nazionale Italiana.

The 1848–49 revolts

On 7 April 1848 Mazzini reached Milan, whose population had rebelled against the Austrian garrison and established a provisional government. The First Italian War of Independence, started by the Piedmontese king Charles Albert to exploit the favourable circumstances in Milan, turned into a total failure. Mazzini, who had never been popular in the city because he wanted Lombardy to become a republic instead of joining Piedmont, abandoned Milan. He joined Garibaldi's irregular force at Bergamo, moving to Switzerland with him.

On 9 February 1849 a republic was declared in Rome, with Pius IX already having been forced to flee to Gaeta the preceding November. On the same day the Republic was declared, Mazzini reached the city. He was appointed, together with Carlo Armellini and Aurelio Saffi, as a member of the "triumvirate" of the new republic on 29 March, becoming soon the true leader of the government and showing good administrative capabilities in social reforms. However, the French troops called by the Pope made clear that the resistance of the Republican troops, led by Garibaldi, was in vain. On 12 July 1849, Mazzini set out for Marseille, from where he moved again to Switzerland.

Late activities

Mazzini spent all of 1850 hiding from the Swiss police. In July he founded the association Amici di Italia (Friends of Italy) in London, to attract consensus towards the Italian liberation cause. Two failed riots in Mantua (1852) and Milan (1853) were a crippling blow for the Mazzinian organization, whose prestige never recovered. He later opposed the alliance signed by Savoy with Austria for the Crimean War. Also in vain was the expedition of Felice Orsini in Carrara of 1853–54.

In 1856 he returned to Genoa to organize a series of uprisings: the only serious attempt was that of Carlo Pisacane in Calabria, which again met a dismaying end. Mazzini managed to escape the police, but was condemned to death by default. From this moment on, Mazzini was more of a spectator than a protagonist of the Italian Risorgimento, whose reins were now strongly in the hands of the Savoyard monarch Victor Emmanuel II and his skilled prime minister, Camillo Benso, Conte di Cavour. The latter defined him as "Chief of the assassins".

In 1858 he founded another journal in London, Pensiero e azione ("Thought and Action"). Also there, on 21 February 1859, together with 151 republicans he signed a manifesto against the alliance between Piedmont and the Emperor of France which resulted in the Second War of Italian Independence and the conquest of Lombardy. On 2 May 1860 he tried to reach Garibaldi, who was going to launch his famous Expedition of the Thousand[20] in southern Italy. In the same year he released Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties of Man"), a synthesis of his moral, political and social thoughts. In mid-September he was in Naples, then under Garibaldi's dictatorship, but was invited by the local vice-dictator Giorgio Pallavicino to move away.

The new Kingdom of Italy was created in 1861 under the Savoy monarchy. In 1862, Mazzini joined Garibaldi in his failed attempt to free Rome. In 1866, Italy joined the Austro-Prussian War and gained Venetia. At this time Mazzini frequently spoke out against how the unification of his country was being achieved, and in 1867 he refused a seat in the Italian Chamber of Deputies. In 1870, he tried to start a rebellion in Sicily, and was arrested and imprisoned in Gaeta. He was freed in October, in the amnesty declared after the Kingdom finally took Rome, and returned to London in mid-December.

Giuseppe Mazzini died of pleurisy at the house known now as Domus Mazziniana in Pisa in 1872, at the age of 66. His body was embalmed by Paolo Gorini. His funeral was held in Genoa, with 100,000 people taking part in it.

Ideology

Mazzini, an Italian nationalist, was a fervent advocate of republicanism and envisioned a united, free and independent Italy. Unlike his contemporary Garibaldi, who was also a republican, Mazzini refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the House of Savoy until after the capture of Rome.

Mazzini was vigorously opposed to Marxism and Communism, and in 1871 he condemned the socialist revolt in France that led to the creation of the short-lived Paris Commune.[21] This later caused Karl Marx to refer to Mazzini as a "reactionary" and an "old ass".[22][23] Mazzini rejected the Marxist doctrines of class struggle and materialism, and stressed the need for class collaboration[21][24]

Mazzini also rejected the classical liberal principles of the Enlightenment based on the doctrine of individualism, which he criticized as "presupposing either metaphysical materialism or political atheism."[25]

Influenced by his Jansenist upbringing, Mazzini's thought is characterized by a strong religious fervor and deep sense of spirituality. Mazzini described himself as a Christian and emphasized the necessity of faith and a relationship with God, while vehemently denouncing rationalism and atheism. His motto was Dio e Popolo ("God and People"). He regarded patriotism as a duty, and love for the Fatherland as a divine mission, saying that the Fatherland was "the home wherein God has placed us, among brothers and sisters linked to us by the family ties of a common religion, history, and language."[26]

In his 1835 publication Fede e avvenire ("Faith and the Future"), he wrote: "We must rise again as a religious party. The religious element is universal and immortal ... The initiators of a new world, we are bound to lay the foundations of a moral unity, a Humanitarian Catholicism."[27] However, Mazzini's relationship with the Catholic Church and the Papacy was not always a kind one. While he initially supported Pope Pius IX upon his election, writing an open letter to him in 1847, he later published a scathing attack against the pope in his Sull'Enciclica di Papa Pio IX ("On the Encyclical of Pope Pius IX") in 1849.

Although some of his religious views were at odds with the Catholic Church and the Papacy, and his writings often were tinged with anti-clericalism, at the same time Mazzini criticized Protestantism, stating that it is "divided and subdivided into a thousand sects, all founded on the rights of individual conscience, all eager to make war on one another, and perpetuating that anarchy of beliefs which is the sole true cause of the social and political disturbances that torment the peoples of Europe."[28]

Mazzini formulated a concept known as thought and action, in which thought and action must be joined together, and every thought must be followed by action, therefore rejecting intellectualism and the notion of divorcing theory from practice.[29] He likewise rejected the concept of the "rights of man" which had developed during the Age of Enlightenment, arguing instead that individual rights were a duty to be won through hard work, sacrifice and virtue, rather than "rights" which were intrinsically owed to man. He outlined his thought in his Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties of Man"), published in 1860.

Women's rights

In Doveri dell'uomo ("Duties of Man", 1860) Mazzini called for recognition of women's rights. After his many encounters with political philosophers in England, France and across Europe, he had decided that the principle of equality between men and women was fundamental to building a truly democratic Italian nation. He called for the end of women's social and judicial subordination to men. His vigorous position heightened attention to gender among European thinkers who were already considering democracy and nationalism. Mazzini helped intellectuals see women's rights not merely a peripheral topic but as a fundamental goal necessary for the regeneration of old nations and the rebirth of new ones.[30] Mazzini admired Jessie White Mario who was described by Giuseppe Garibaldi as the "Bravest Woman of Modern Time". Jessie joined Garibaldi's Redshirts for the 1859-1860 campaign. As a correspondent for the Daily News she witnessed almost every fight that had brought on the unification of Italy.[31]

Mazzini and Marx

Karl Marx, in an interview by R. Landor from 1871, said that Mazzini's ideas represented "nothing better than the old idea of a middle-class republic." Marx believed, especially after the Revolutions of 1848, that Mazzini's point of view had become reactionary, and the proletariat had nothing to do with it.[22] In another interview, Marx described Mazzini as "that everlasting old ass".[23]

Mazzini, in turn, described Marx as "a destructive spirit whose heart was filled with hatred rather than love of mankind" and declared that "Despite the communist egalitarianism which [Marx] preaches he is the absolute ruler of his party, admittedly he does everything himself but he is also the only one to give orders and he tolerates no opposition."[32]

Legacy

Mazzini's socio-political thought has been referred to as Mazzinianism, and his worldview as the Mazzinian Conception, terms which were later utilized by Benito Mussolini and Fascists such as Giovanni Gentile to describe their political ideology and spiritual conception of life.[25][29][33][34]

Metternich described Mazzini as "the most influential revolutionary in Europe."[35]

Carl Schurz, in Volume I of his 'Reminiscences' (New York: McClure's Publ. Co., 1907, see Chapters XIII and XIV), gives a biographical sketch of Mazzini and recalls two meetings he had had with him when they were both in London in 1851.

While the book 10,000 Famous Freemasons by William R. Denslow lists Mazzini as a Mason, and even a Past Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy, articles on the Grand Orient of Italy's own website question whether he was ever a regular Mason and do not list him as a Past Grand Master.[36]

Often viewed in the Italy of the time as a god-like figure, Mazzini was nonetheless denounced by many of his compatriots as a traitor. Contemporary historians tended to believe that he ceased to contribute anything productive or useful after 1849, but modern ones take a more favorable opinion of him. The antifascist Mazzini Society, founded in the United States in 1939 by Italian political refugees, took his name; they, like him, served Italy from exile.

In London, Mazzini resided at 155 North Gower Street, near Euston Square, which is now marked with a commemorative blue plaque.[37] (155 is next door to 157 North Gower Street, which doubles as 221b Baker Street in the BBC adaptation of Sherlock.). A plaque on Laystall Street in Clerkenwell, London's Little Italy during the 1850s, also pays tribute to Giuseppe Mazzini.[38]

A bust of Mazzini is in New York's Central Park between 67th and 68th streets just west of the West Drive.

The 1973–1974 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honor.

See also

Works

- Warfare against the Man (1825)

- On Nationality (1852)

- The Duties of Man and Other Essays (1860). J.M. Dent & Sons, London, 1907 ISBN 1596052198

- A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations Recchia, Stefano, and Urbinati, Nadia, editors. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Articles

- "Is it Revolt or a Revolution?" in Tait's Edinburgh Magazine, June 1840, pp. 385–390

Footnotes

- Romani, Roberto (2018). Sensibilities of the Risorgimento: Reason and Passions in Political Thought. BRILL. pp. 147–157.

- Finn, Margot C. (2003). After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848-1874. Cambridge University Press. p. 200.

- Finn, Margot C. (2003). After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848-1874. Cambridge University Press. pp. 170–176.

- "Mazzini, Giuseppe". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Mazzini". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Mazzini". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- The Italian Unification

- (2013) Delphi Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne

- Giuseppe Mazzini's International Political Thought

- Hunt, Lynn; Martin, Thomas R.; and Rosenwein, Barbara H. Peoples and Cultures, Volume C ("Since 1740"): The Making of the West. Boston: Bedford/Saint Martin's, 2008.

- Sarti, Roland (1 January 1997). Mazzini: A Life for the Religion of Politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-275-95080-4. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "The Oath of Young Italy". www.mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Though an adherent of the group, Mazzini was not Christian.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1994). Mazzini. Yale University Press. pp. 11–12.

- Which was also reformed in 1840 in Paris, thank to the help of Giuseppe Lamberti.

- Verdecchia, Enrico. Londra dei cospiratori. L'esilio londinese dei padri del Risorgimento, Marco Tropea Editore, 2010

- By the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, 2nd Baronet.

- Directly in the person of the Foreign Secretary, George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen.

- In the person of Baron Philipp von Neumann.

- Which, apparently, was to follow a plan previously devised by Mazzini himself.

- Stefano Recchia, Nadia Urbinati (2009) A Cosmopolitanism of Nations; Princeton University Press.; p. 6

- Interview with Karl Marx, head of L'Internationale by R. Landor, New York World, 18 July 1871, reprinted Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, 12 August 1871 – World History Archives: The retrospective history of the world's working class

- Pearce R, Stiles A: The Unification of Italy, Third Edition, Hodder Murray, 2006.

- Joan Campbell (1992, 1998) European Labor Unions; Greenwood Press; p. 253

- M. E. Moss (2004) Mussolini's Fascist Philosopher: Giovanni Gentile Reconsidered; New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.; p. 59-60

- E. A. V., Joseph Mazzini (1875) A Memoir by E. A. V. With Two Essays by Mazzini; Henry S. King & Co.; p. 2

- G. Mazzini, Fede e avvenire, Cambridge University Press, 1921 p.51

- Mazzini, Joseph. The Duties of Man. London; Chapman & Hall, 193, Piccadilly. Pp. 52.

- Paul Schumaker (2010) The Political Theory Reader; Wiley-Blackwell; p. 58

- Federica Falchi, "Democrazia e questione femminile nel pensiero di Giuseppe Mazzini" ['Democracy and the rights of women in the thinking of Giuseppe Mazzini'] Modern Italy (2012) 17#1 pp 15–30.

- Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 13 Apr 1906, Fri, Page 13 https://www.newspapers.com/clip/25083191/bravest_woman_of_modern_times_jessie/

- as quoted in Fritz J. Raddatz (1975, 1978) Marx: A Political Biography; Boston: Little, Brown; p. 66

- Maurizio Viroli (2012) As If God Existed: Religion and Liberty in the History of Italy; p. 177-178

- Origins and Doctrine of Fascism Giovanni Gentile (1932) Origins and Doctrine of Fascism; p. 5-6

- David Gress (1998) From Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its Opponents; Free Press

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Giuseppe Mazzini – London Remembers". londonremembers.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "In search of London's Little Italy – Londonist". londonist.com. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

Further reading

- Bayly, C. A., and Eugenio F. Biagini, eds. "Giuseppe Mazzini and the Globalisation of Democratic Nationalism 1830–1920 (2009)

- Claeys, Gregory. "Mazzini, Kossuth, and British Radicalism, 1848–1854," Journal of British Studies, vol. 28, o. 3 (July 1989), pp. 225–261. In JSTOR.

- Dal Lago, Enrico. ""We Cherished the Same Hostility to Every Form of Tyranny": Transatlantic Parallels and Contacts between William Lloyd Garrison and Giuseppe Mazzini, 1846–1872." American Nineteenth Century History 13.3 (2012): 293–319.

- Dal Lago, Enrico. William Lloyd Garrison and Giuseppe Mazzini: Abolition, Democracy, and Radical Reform. (Louisiana State University Press, 2013).

- Falchi, Federica. "Democracy and the rights of women in the thinking of Giuseppe Mazzini." Modern Italy 17#1 (2012): 15–30.

- Finelli, Michele. "Mazzini in Italian historical memory." Journal of Modern Italian Studies (2008) 13#4 pp 486–491.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1996). Mazzini. Yale University Press., a standard scholarly biography.

- Ridolfi, Maurizio. "Visions of republicanism in the writings of Giuseppe Mazzini," Journal of Modern Italian Studies (2008) 13#4 pp 468–479.

- Sarti, Roland. "Giuseppe Mazzini and his opponents" in John A. Davis, ed. Italy in the Nineteenth Century: 1796–1900 (2000) pp 74–107 online

- Sarti, Roland. Mazzini: A Life for the Religion of Politics (1997) 249pp

- Urbinati, Nadia. "Mazzini and the making of the republican ideology." Journal of Modern Italian Studies 17.2 (2012): 183–204.

- Wight, Martin; Wight, Gabriele, and Porter, Brian (Eds.) Four Seminal Thinkers in International Theory: Machiavelli, Grotius, Kant, and Mazzini Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005

Primary sources

- Mazzini, Giuseppe. A cosmopolitanism of nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's writings on democracy, nation building, and international relations (Princeton University Press, 2009).

Other languages

- Chabod, Federico (1967). L'idea di nazione. Bari: Laterza.

- Omodeo, Adolfo (1955). L'età del Risorgimento italiano. Naples: ESI.

- Omodeo, Adolfo (1934). "Introduzione a G. Mazzini". Scritti scelti. Milan: Mondadori.

- Giuseppe Leone e Roberto Zambonini, "Mozart e Mazzini – Paesaggi poetico-musicali tra flauti magici e voci "segrete", Malgrate, Palazzo Agudio, 25 agosto 2007, ore 21.

Partial text of this article

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mazzini, Giuseppe. |

- "JOSEPH MAZZINI (Obituary Notice, Tuesday, March 12, 1872)". Eminent Persons: Biographies reprinted from The Times. I (1870-1875). London: Macmillan and Co. 1892. pp. 83–91. Retrieved 26 February 2019 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- Works by Giuseppe Mazzini at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Giuseppe Mazzini at Internet Archive

- Biography at cronologia.it (in Italian)

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

.jpg)