Santa Croce, Florence

The Basilica di Santa Croce (Basilica of the Holy Cross) is the principal Franciscan church in Florence, Italy, and a minor basilica of the Roman Catholic Church. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 meters south-east of the Duomo. The site, when first chosen, was in marshland outside the city walls. It is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, the poet Foscolo, the philosopher Gentile and the composer Rossini, thus it is known also as the Temple of the Italian Glories (Tempio dell'Itale Glorie).

| Basilica di Santa Croce | |

|---|---|

| Basilica of the Holy Cross | |

_-_Facade.jpg) Façade of Santa Croce, September 2013 | |

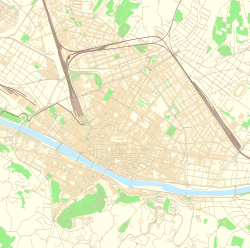

Basilica di Santa Croce Location in Florence | |

| 43°46′6.3″N 11°15′45.8″E | |

| Location | Florence, Tuscany |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Status | Minor basilica |

| Consecrated | 1443 |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic, Renaissance, Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1294-1295 |

| Completed | 1385 |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Florence |

Building

The Basilica is the largest Franciscan church in the world. Its most notable features are its sixteen chapels, many of them decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils,[lower-alpha 1] and its tombs and cenotaphs. Legend says that Santa Croce was founded by St Francis himself. The construction of the current church, to replace an older building, was begun on 12 May 1294,[2] possibly by Arnolfo di Cambio, and paid for by some of the city's wealthiest families. It was consecrated in 1442 by Pope Eugene IV. The building's design reflects the austere approach of the Franciscans. The floorplan is an Egyptian or Tau cross (a symbol of St Francis), 115 metres in length with a nave and two aisles separated by lines of octagonal columns. To the south of the church was a convent, some of whose buildings remain.

The Primo Chiostro, the main cloister, houses the Cappella dei Pazzi, built as the chapter house, completed in the 1470s. Filippo Brunelleschi (who had designed and executed the dome of the Duomo) was involved in its design which has remained rigorously simple and unadorned.

In 1560, the choir screen was removed as part of changes arising from the Counter-Reformation and the interior rebuilt by Giorgio Vasari. As a result, there was damage to the church's decoration and most of the altars previously located on the screen were lost. At the behest of Cosimo I, Vasari plastered over Giotto's frescoes and placed some new altars.[3]

The bell tower was built in 1842, replacing an earlier one damaged by lightning. The neo-Gothic marble façade dates from 1857-1863. The Jewish architect Niccolo Matas from Ancona, designed the church's façade, working a prominent Star of David into the composition. Matas had wanted to be buried with his peers but because he was Jewish, he was buried under the threshold and honored with an inscription.

In 1866, the complex became public property, as a part of government suppression of most religious houses, following the wars that gained Italian independence and unity.[4][5]

The Museo dell'Opera di Santa Croce is housed mainly in the refectory, also off the cloister. A monument to Florence Nightingale stands in the cloister, in the city in which she was born and after which she was named. Brunelleschi also built the inner cloister, completed in 1453.

In 1940, during the safe hiding of various works during World War II, Ugo Procacci noticed the Badia Polyptych being carried out of the church. He reasoned that this had been removed from the Badia Fiorentina during the Napoleonic occupation and accidentally re-installed in Santa Croce.[6] Between 1958 and 1961, Leonetto Tintori removed layers of whitewash and overpaint from Giotto's Peruzzi Chapel scenes to reveal his original work.[1]

In 1966, the Arno River flooded much of Florence, including Santa Croce. The water entered the church bringing mud, pollution and heating oil. The damage to buildings and art treasures was severe, taking several decades to repair.

Today the former dormitory of the Franciscan friars houses the Scuola del Cuoio (Leather School).[7] Visitors can watch as artisans craft purses, wallets, and other leather goods which are sold in the adjacent shop.

Renovations

The basilica has been undergoing a multi-year restoration program with assistance from Italy’s civil protection agency. [8] On 20 October 2017, the property was closed to visitors due to falling masonry which caused the death of a tourist from Spain.[9][10] The basilica was closed temporarily during a survey of the stability of the church.[11][12] The Italian Ministry of Culture said that "there will be an investigation by magistrates to understand how this dramatic fact happened and whether there are responsibilities over maintenance."

Art

Artists whose work is present in the church include:

- Benedetto da Maiano (pulpit; doors to Cappella dei Pazzi, with his brother Giuliano)

- Antonio Canova (Alfieri's monument)

- Cimabue (Crucifixion, badly damaged by the 1966 flood and now in the refectory)

- Andrea della Robbia (altarpiece in Cappella Medici)

- Luca della Robbia (decoration of Cappella dei Pazzi)

- Desiderio da Settignano (Marsuppini's tomb; frieze in Cappella dei Pazzi)

- Donatello (relief of the Annunciation on the south wall; crucifix in the lefthand Cappella Bardi; St Louis of Toulouse in the refectory, originally made for the Orsanmichele)

- Agnolo Gaddi (frescoes in Castellani Chapel and chancel; stained glass in chancel)

- Taddeo Gaddi (frescoes in the Baroncelli Chapel; Crucifixion in the sacristy; Last Supper in the refectory, considered his best work)

- Giotto (frescoes in Cappella Peruzzi and righthand Cappella Bardi; possibly Coronation of the Virgin, altarpiece in the Baroncelli Chapel, also attributed to Taddeo Gaddi)

- Giovanni da Milano (frescoes in Cappella Rinuccini) with Scenes of the Life of the Virgin and the Magdalen

- Maso di Banco (frescoes in Cappella Bardi di Vernio) depicting Scenes from the life of St.Sylvester (1335–1338).

- Henry Moore (statue of a warrior in the Primo Chiostro)

- Andrea Orcagna (frescoes largely disappeared during Vasari's remodelling, but some fragments remain in the refectory)

- Antonio Rossellino (relief of the Madonna del Latte (1478) in the south aisle)

- Bernardo Rossellino (Bruni's tomb)

- Santi di Tito (Supper at Emmaus and Resurrection, altarpieces in the north aisle)

- Giorgio Vasari (Michelangelo's tomb) with sculpture by Valerio Cioli, Iovanni Bandini, and Battista Lorenzi. Way to Calvary painted by Vasari.[13]

- Domenico Veneziano (SS John and Francis in the refectory)

Once present in the church's Medici Chapel, but now split between the Florentine Galleries and the Bagatti Valsecchi Museum in Milan, is a polyptych by Lorenzo di Niccolò, whilst the Novitiate Altarpiece by Filippo Lippi and a predella by Pesellino was painted for the church's Novitiate Chapel.

The Bardi Chapel features Giotto's Death of St. Francis, a work which was restored heavily in the 19th century; these restorations were later removed to study the areas which are definitively Giotto's, leaving portions of the painting missing.[14]

Funerary monuments

The Basilica became popular with Florentines as a place of worship and patronage and it became customary for greatly honoured Florentines to be buried or commemorated there. Some were in chapels "owned" by wealthy families such as the Bardi and Peruzzi. As time progressed, space was also granted to notable Italians from elsewhere. For 500 years monuments were erected in the church including those to:

- Leon Battista Alberti (15th-century architect and artistic theorist)

- Giovan Vincenzo Alberti (Florentine senator and minister to first two Lorraine Grand-Dukes)

- Vittorio Alfieri (18th-century poet and dramatist)

- Eugenio Barsanti (co-inventor of the internal combustion engine)

- Lorenzo Bartolini (19th-century sculptor)

- Julie Clary, wife of Joseph Bonaparte, and their daughter Charlotte Napoléone Bonaparte

- Leonardo Da Vinci (commemorative plaque, buried in Château d'Amboise in France)

- Leonardo Bruni (15th-century chancellor of the Republic, scholar and historian)

- Dante (buried in Ravenna)

- Ugo Foscolo (19th-century poet)

- Galileo Galilei

- Giovanni Gentile (20th-century philosopher)

- Lorenzo Ghiberti (artist and bronze-smith)

- Giovanni Lami

- Niccolò Machiavelli by Innocenzo Spinazzi

- Carlo Marsuppini (15th-century chancellor of the Republic of Florence)

- Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Raffaello Morghen (19th-century engraver)

- Giovanni Battista Niccolini poet

- Gioachino Rossini by Giuseppe Cassioli

- Louise of Stolberg-Gedern (wife of Charles Edward Stuart, 'Bonnie Prince Charlie')

- Guglielmo Marconi (buried in his birthplace at Sasso Marconi, near Bologna)

- Enrico Fermi (nuclear physicist, memorial only - Fermi is buried in Chicago, Illinois)

Cloister Monuments

Michelangelo's tomb

Michelangelo's tomb_(14782103635).jpg) Machiavelli's tomb

Machiavelli's tomb Galileo's tomb

Galileo's tomb

In literature

- A Room with a View (1908), E.M. Forster, chapter 2

- Romola (1863), George Eliot

References

Footnotes

Citations

- Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 139. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- Chiarini, Gloria (2007). "Basilica of Santa Croce". Florence Art Guide. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- Cuminetti, Vittorio; Bonechi, Giampaolo, eds. (1969). Florence: Glory of the Art. Bonechi Editore. p. 39.

- Besse, J M (1911). "Suppression of Monasteries in Continental Europe: C. Italy". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- "Santa Croce: Overview". Opera of Santa Croce. Archived from the original on 28 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. pp. 107–8. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- http://www.leatherschool.com Archived 2006-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Associated Press (October 20, 2017). "Tourist killed by falling masonry at famous Florence church". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Agency (October 19, 2017). "Florence tourist death: Falling masonry kills Spanish visitor to Basilica di Santa Croce". The Independent. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Downs, Ray (October 19, 2017). "Tourist killed by falling stone at famous Italian church". UPI. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Associated Press (October 29, 2017). "Tourist killed by falling masonry in famous Florence church". The Guardian. Milan. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Gasperetti, Maco (October 20, 2017). "Collapse at Santa Croce in Florence despite safety measures". Corriere.it. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Borsook, Eve (1991). Vincent Cronin (ed.). The Companion Guide to Florence, 5th Edition. HarperCollins; New York. pp. 100–104.

- De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. pp. 572–73. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

External links

![]()

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Croce (Florence). |

- Official website (in Italian)

- Museums of Florence | Church and Museum of Santa Croce

- BBC video about Giotto frescoes in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence