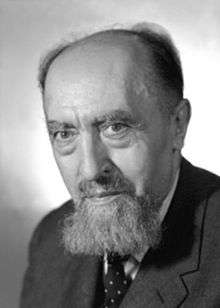

Alessandro Casati

Alessandro Casati (5 March 1881 – 4 June 1955) was an Italian academic, commentator and politician. He served as a senator between 1923 and 1924 and again between 1948 and 1953. He also held ministerial office, most recently as Minister of War for slightly more than twelve months during 1944/45, serving under "Presidente del Consiglio" ("Prime Minister...") Bonomi.[1][2][3][4]

Alessandro Casati | |

|---|---|

Count Alessandro Casati | |

| Born | 5 March 1881 |

| Died | 4 June 1955 |

| Alma mater | Collegio Alessandro Manzoni, Merate, Lombardy, Italy |

| Occupation | commentator-journalist politician |

| Political party | ANPI PLI |

| Spouse(s) | Leopolda Incisa della Rocchetta (1873 – 1960) |

| Children | Alfonso Casati (1918 – 1944) |

| Parent(s) | Gian Alfonso Casati (1854 – 1890) Luisa Negroni Prati Morosini (1857 – 1927) |

Biography

Provenance and early years

Count Alessandro Casati was born in Milan,[5] the younger son of Gian Alfonso Casati (1854 – 1890) by his marriage to Luisa Negroni Prati Morosini (1857 – 1927).[2] The Casatis came from the Milanese nobility: they could trace their ancestry back more than eight hundred years. Family was important. In the judgment of one commentator, family ancestry influenced Count Alessandro more deeply than mere dynastic awareness. The recollections of friends along with his own letters and writings attest to a constant habit of invoking people and practices from the past in order to correct present disjunctures, usually without any very obvious awareness of solutions that might emerge through a process of continuity.[1] Public service ran in the blood: Gabrio Casati and Camillo Casati were uncles.[3]

Philosophy

Sources describe him variously as a "religious liberal" or as a "liberal modernist". His upbringing was privileged and heavily influenced by the nineteenth century liberalism that in Italy had grown out of eighteenth century enlightenment ideals.[1] He was a student at the "Alessandro Manzoni College" ("Collegio Alessandro Manzoni") in Merate.[6] An influence from his adolescence that recurs most frequently in Casati's writings is the wily pragmatic economist-politician Stefano Jacini. But Alessandro Casati also lived through the social ructions and the neo-conservatism that grew out the rapid industrialisation during the closing decades of the nineteenth century. Through the prisms of these influences and experiences he emerged as a voice for social and political stabilisation and moderation, first through the Giolitti years, and later under Fascism.[1]

Commentator and networker

He was also, as a young man, an enthusiastic child of Modernism, both in terms of his religion and more broadly. This was apparent from his contributions to Il Rinnovamento (loosely "Renewal"), a short-lived Milan-based literary and cultural bi-monthly magazine which he co-founded with Tommaso Gallarati Scotti and Antonio Aiace Alfieri, and which was launched in January 1907.[3] It was a magazine produced by and for angry youth: Scotti described Rinnovamento as "not simply a reaction against religious conservatism ... [but] also a reaction against the neo-paganism, the neo-aestheticism, the positivism and the scepticism that were corrupting the Italian soul".[1] During these early years of the twentieth century Casati was also a significant contributor to Leonardo, a literary magazine (which was described as a monthly publication and appeared slightly irregularly between 1903 and 1907) and La Voce, a more influential magazine produced (also rather irregularly) in Florence between 1908 and 1916.[3] Casati's contributions to these publications brought him to the wider attention of Italy's intellectual class, including several literary celebrities of the day. A particular case in point was the philosopher-politician Benedetto Croce. Context for Casati's view of the world was provided by his religious belief. Croce, in contrast, had robustly and permanently rejected religion during his teenage years. Despite such fundamental difference, Casati and Croce became life-long friends:[7] abundant evidence for their mutual respect and affection survives in their sometimes combative correspondence that runs for more than forty years.[2] After Il Rinnovamento folded in 1909 Alessandro Casati was involved in discussions about launching a new literary-political publication, but he was never by nature a polemicist, increasingly demonstrating a certain constrained detachment with regard the surging intellectual currents of the times: such discussions - at least as far as Casati was concerned - came to nothing. One source refers to his evident wish, at this time, to retreat into an inscrutable process of ethical and intellectual "self-discipline".[1][lower-alpha 1]

War

Alessandro Casati was not among those who professed themselves surprised by the outbreak of war at the end of July 1914, and he regarded Italy's military intervention in April 1915 as an inevitable if deplorable development.[1] He participated in the fighting, ending the war with the rank of "Tenente colonnello" ("Lieutenant colonel"), having received the Bronze and Silver Medals of Military Valor ("...medagliere di bronzo e d'argento al valor militare"). He fought at the Battle of Asiago, led the successful attack by the 127th infantry regiment of the Florence Brigade at Monte Kobilek and was badly wounded at Bainsizza, following which he needed an operation. He also fought with his "Alpini" forces against the Austrians in the so-called "White War" in and around the Tonale Pass in the mountains north of Bergamo and Brescia.[2] There are also a number of reports, albeit not formally confirmed, that during 1917 Alessandro Casati became a close associate of his fellow Lombard, General Capello, commander of the Second Army, providing critical advice and practical support, notably in respect of using innovative propaganda techniques to sustain troop morale, both before and after the important Battle of Caporetto.[1] Capello was considered unusual in senior military circles because of the way he liked to surround himself with "intellectuals", and the "catholic liberal" Alessandro Casati was prominent among these.[8]

Public service

Casati's record during the war had in any event raised his profile with the Italian political establishment and in the immediate aftermath of it he was entrusted with several important political-diplomatic assignments.[1] In September 1923 he accepted an invitation from the Education Minister, Giovanni Gentile, to take on the vice presidency of the country's "Higher Education Council" ("Consiglio superiore della Pubblica Istruzione"), a body charged with ensuring the efficacy and consistency of Gentile's schools reforms.[2][1] Already in March 1923 he had accepted nomination as a member of the senate.[5][9] The senate was (and is) the upper house of Italy's bicameral parliament. One of twenty-two nominees accepted on that occasion, he was proposed for senate membership by his old friend, the senator Benedetto Croce.[2]

Casati joined the government as part of the cabinet re-shuffle of 1 July 1924, taking over from Giovanni Gentile at the Education Ministry. Politically he was, at this stage, a still slightly semi-detached member the group around the former "Presidente del Consiglio" ("Prime Minister..."), Antonio Salandra.[1] The murder, in a Lancia Lambda on 10 June 1924, of the anti-fascist politician Giacomo Matteotti was widely blamed on Fascist thugs: it triggered a widespread political and public backlash against the increasingly autocratic Mussolini government.[10] As the political temperature rose, on 3 January 1925 Benito Mussolini delivered a speech to the lower house of parliament "Camera dei deputati" accepting "moral" but "not material" responsibility for the Matteotti murder.[11] He assured the parliament that within the next 48 hours the situation would be clarified. That indeed proved to be the case: Interior Minister Luigi Federzoni sent out a precise instruction to the prefects (regional administrators) which had the effect of drastically restricting press freedom and closing down political opposition parties across the country. If it had not been clear before, it was now impossible to avoid the reality that Italy was well advanced along the path to one-party dictatorship.[12] 3 January 1925, the date of that Mussolini speech to a recalcitrant parliament, was also the day on which Alessandro Casati resigned from the Mussolini government.[2][4] In the immediate term this appeared to mean joining Francesco Ruffini and Luigi Albertini in political opposition to the government from within the senate,[2] but in reality it was Albertini whose example he now followed, , withdrawing from both the political stage and from public life more broadly.[1][3]

Scholarship

Correspondence with his friend Benedetto Croce indicates that Casati had difficulty adjusting to the reduction in the size of his social circle that followed his withdrawal from public life.[1][13] The years that followed were to be his most productive in terms of his writing, however.[1] His 1931 essay and subsequent work on the memoires of Giuseppe Gorani and the Seven Years' War date from this period.[3][14] He also devoted himself to preparing a three volume historical work on contemporary Italian history.[3] This was never published, however. The papers he had gathered and the drafts he had prepared for it were destroyed in February 1943 when most of his "palazzo" in Milan, including the rich and extensive Casati family library which he had inherited and then greatly extended,[2] were destroyed by British bombing.[1][15] (Casati nevertheless continued to receive friends in the two rooms that survived in the rubble.) Later he relocated to a new home at Arcore, a short distance to the northeast of the city centre.[2]

1943

The first half of 1943 the saw an unfolding collapse of the Fascist regime. During this period Alessandro teamed up with others to prepare for a re-emergence of the "Partito Liberale Italiano" (PLI / "Liberal Party..."...) which by this time had been outlawed for twenty years.[1] Nevertheless, Mussolini's Grand Council colleagues only actually removed their leader him from power on 25 July 1943: Alessandro Casati's political activity during the first half of that year took place under conditions of considerable secrecy. However, a letter dated 10 April 1943 survives which he addressed from Rome to Benedetto Croce, inviting Croce to join the "new", still "underground", Liberal Party.[1] (Croce became "party president" later in 1943 or early in 1944.) By September 1943 Casati had become the PLI representative on the "Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN / ""National Liberation Committee").[3]

As Fighting drew closer to Rome, in November 1943 Casati was one of several leading politically active anti-fascists who took refuge in the pontifical seminary at San Giovanni in Laterano. Others included the socialist Pietro Nenni, the Christian Democrat Alcide De Gasperi, the former radical Meuccio Ruini and the democratic socialist Ivanoe Bonomi.[lower-alpha 2] These were some of the founder members of the emerging National Liberation Committee (CLN) which became the political face of Italian resistance would oversee the transition from Fascism to multi-party democracy after the liberation of Rome from (by this point) German military control in June 1944.[1]

Alfonso

Alfonso Casati (1918 – 1944) was the much loved only son of Alessandro and Leopolda Casati. Alfonso volunteered for service in the Liberation Corps in May 1944. He was assigned to the Special Battalion of the First Grenadiers. In command of the "Bafile" battalion he took part in the fighting for control over Belvedere Ostrense and Corinaldo (near Ancona) which were being held by the Germans as strongholds along the "Heinrich line". While protecting the retreat of Polish and Italian units serving with his platoon, Alfonso Casati was shot dead by a German mortar at Corinaldo on 6 August 1944.[1][16] He became a posthumous recipient of the Medaglia di bronzo al valor militare.[16]

Postwar

The short-lived Badoglio coalition government fell following the liberation of Rome. A new multi-party coalition under the leadership of Ivanoe Bonomi took over on 18 June 1944, formally appointed by the crown prince, and with the approval of the British military commander on the ground (if not, at this stage, of the British and American governments). The Bonomi cabinet was, in effect, the CLI as government. Alessandro Casati served under Bonomi between 18 June 1944 and 21 June 1945 as Minister of War.[17] He used this as an opportunity to help build up the strength of the Corpo Italiano di Liberazione (Liberation corps) and implement various military reforms of a technical nature. These included the (re-)establishment of the "Legnano" and "Cremona" battalions which, along with the "Arma dei Carabinieri", helped allied forces break through the German defensive "Gothic line" in northern central Italy.[1]

After he was succeeded at the ministry by his friend Stefano Jacini in June 1945, Alessandro Casati became president of the "Consiglio supremo di difesa" ("Supreme Defence Council").[1][18] There were a number of other public service and government appointments during Casati's final decade.[19] of which one of the more significant was his appointment as a member of the Italian delegation to UNESCO. In May/June 1950 he presided over the UNESCO General Conference, held on that occasion in Florence.[2][20]

A new constitution, signed off at the end of 1947, meant a new senate, instituted on 1 January 1948 (although the new republican senate continued to meet in the Palazzo Madama, just as the old senate had under the monarchy). Alessandro Casati was nominated to membership of the (greatly enlarged) republican senate on 1 April 1948, formally on the basis that he had been a member of the old senate.[19] He was elected president of the Liberal Party group of senators on 8 May 1948, retaining this position till 24 June 1953.[19]

He was elected to the ruling council of the Italian Institute for the Study of History ("Istituto italiano per gli studi storici") and to the presidency of the National Council of Public Instruction ("Consiglio nazionale della pubblica istruzione").[1][21] He became a member of the Dante Alighieri Society between 1953 and 1955,[22] and of the Italian Press Association ("Federazione Nazionale Stampa Italiana").[3] Between 1951 and 1954 he was, in addition, a member of the Italian Association of Librarians, and between 1952 and 1955 he resumed his membership of the Lombardy History Society, with which he had already been closely involved during the first two decades of the twentieth century.[3] He was also president of the commission charged with the publication of Cavour's correspondence and related diplomatic documents.[1]

Final months

During his final months, which were marred by serious illness, Alessandro Casati retreated to his villa at Arcore, ordering his affairs and entrusting some surviving inherited ancestral papers from his Teresa Casati and Federico Confalonieri to the Risorgimento Museum in Milan.[1]

He died on 4 June 1955. Senior senators paid tribute to his scholarship, his generosity and modesty complemented by powerful persuasiveness in argument, his shrewd judgment, his courage as a soldier and politician, and his over-riding patriotism.[2]

His physical remains are buried, alongside those of his wife and of the son who predeceased them both, in the family masoleum at the Muggiò municipal cemetery, near to the family home of his later years at Arcore.[23]

Awards and honours

Notes

- "... la sua volontà ripiegare in un imperscrutabile processo di autodisciplina etico-intellettuale."[1]

- Many Italian national politicians would subsequently switch between political parties. Casati did not, however.

References

- Piero Craveri. "Casati, Alessandro". Enciclopedia on line. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana (Enciclopedia Treccani), Roma. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Casati, Alessandro". Senato della Repubblica. Senato della Repubblica. 7 June 1955. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Fondo Alessandro Casati". Biblioteca Comunale Centrale di Milano, Sezione Manoscritti. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Alessandro Casati, Nato a Milano il 5 marzo 1881, deceduto ad Arcore (oggi Monza) il 4 giugno 1955, storico e uomo politico liberale". Donne e uomini della Resistenza. Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia (ANPI). 25 July 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Walter Maturi (1948). "Casati, Alessandro, conte". Enciclopedia Italiana - II Appendice. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana (Enciclopedia Treccani), Roma. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Federico Mazzei (2013). "Dal modernismo a Croce: il liberalismo «religioso» di Alessandro Casati" (PDF). Cattolici e liberali dall’antifascismo alla seconda guerra mondiale (1925-1943). Università degli Studi di Bologna (Alma Mater Studiorum). pp. 139–155. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Giovanni D’Alessandro (15 July 2012). "Quando il filosofo Benedetto Croce era di casa ad Arcore". Foto dei primi anni ’20 svela l’amicizia col marchese Casati Uno studio personale nell’attuale dimora di Berlusconi. Il Centro SpA, Pescara. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Gian Luigi Gatti. "Il Servizio P. Propaganda, Assistenza, Vigilanza" (PDF). L'Italia e la Grande Guerra: 1918, Il vittoria e il sacrificio (essay collection). Ministero della Difesa, Roma. pp. 197–202. ISBN 978-8-89818-539-9. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Decreto 1 marzo 1923". Gazzetta ufficiale. 3 March 1923. p. 1481.

- Silvia Morosi; Paolo Rastelli (10 June 2017). "Giacomo Matteotti, morte di un antifascista". Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Benito Mussolini. "Il discorso di Mussolini sul delitto Matteotti". Storia XXI secolo. Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia della Provincia di Roma. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Velia Iacovino (3 January 2015). "3 gennaio 1925: è l'inizio della dittatura fascista". Futuro Quotidiano, Roma. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Benedetto Croce (1969). Epistolario: Lettere ad Alessandro Casati, 1907-1952. Istituto italiano per gli studi storici.

- Giuseppe Gorani; a cura di Alessandro Casati. Memorie di Giovinezza e di guerra (1740 - 1763). Mondadori. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Mauro Colombo (6 May 2003). "I bombardamenti aerei su Milano durante la II guerra mondiale". Storia di Milano. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Alfonso Casati, Nato a Milano il 13 luglio 1918, caduto a Corinaldo (Ancona) il 6 agosto 1944, studente in Lettere, Medaglia d'oro al valor militare alla memoria". Donne e uomini della Resistenza. Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia (ANPI). 25 July 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Casati, Alessandro". Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana (Enciclopedia Treccani), Roma. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Aldo a. Mola. "I Ministri della Difesa. 1945-1955 .... Un cometa di Ministri della Guerra nel vortice tra guerra e trattato di pace." (PDF). Italia 1945-1955 la ricostruzione del Paese. Ministero della Difesa (Ufficio Storico dello SMD). pp. 45–57. ISBN 978-88-98185-09-2. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Alessandro Casati: ...Incarichi e uffici ricoperti nella Legislatura". Scheda di attività. Senato della Repubblica. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Maria Paola Azzario Chiesa (2000). L'Italie pour l'Unesco. 50 années de la Commission italienne. Armando Editore. p. 19. ISBN 978-88-8358-099-4.

- "Casati Alessandro". sistema archivistico nazionale. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Dante Aligheri, Società Nazionale". Enciclopedia Italiana - III Appendice. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana (Enciclopedia Treccani), Roma. 1961. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Turismo: Cosa vedere in città". Pro Loco città di Muggio. Amministrazione comunale, Città di Muggio. Retrieved 6 November 2019.