Albert Kahn (architect)

Albert Kahn (March 21, 1869 – December 8, 1942) was the foremost American industrial architect of his day. He is sometimes called the "architect of Detroit". In 1943, the Franklin Institute awarded him the Frank P. Brown Medal posthumously.[1] Many of Albert Kahn's personal working papers and construction photographs are housed at the University of Michigan's Bentley Historical Library.[2] His personal working library, the Albert Kahn Library Collection, is housed at Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, MI.[3] The Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian house most of the family's correspondence and other materials.[4]

Albert Kahn | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | March 21, 1869 |

| Died | December 8, 1942 (aged 73) Detroit, Michigan, US |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | architect |

| Relatives | Julius Kahn, brother Albert E. Kahn, nephew |

Biography

Kahn was born to a Jewish family[5] on March 21, 1869, in Rhaunen, Kingdom of Prussia. Kahn immigrated with his family to Detroit in 1880, when he was 11.[6] His father Joseph was trained as a rabbi; his mother Rosalie had a talent for the visual arts and music.[6]

As a teenager, Kahn got a job at the architectural firm of Mason and Rice.[6] In 1891, he won a year's scholarship to study abroad in Europe, where he toured Germany, France, Italy, and Belgium with Henry Bacon, another young architecture student. Bacon later designed the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C..[6][7]

In 1895, he founded the architectural firm Albert Kahn Associates.[8] Together with his younger brother Julius, he developed a new style of construction whereby reinforced concrete replaced wood in factory walls, roofs, and supports. This gave better fire protection and allowed large volumes of unobstructed interior. Packard Motor Car Company's factory, designed in 1903, was the first to be built according to this principle.[9]

The success of the Packard plant interested Henry Ford in Kahn's designs. Kahn designed Ford Motor Company's Highland Park plant, begun in 1909, where Ford consolidated production of the Ford Model T and perfected the assembly line.[10][11]

Kahn later designed, in 1917, the massive half-mile-long Ford River Rouge Complex in Dearborn, Michigan. The Rouge developed as the largest manufacturing complex in the United States and, in its time, in the world. Its workforce peaked at 120,000 workers.

Kahn was responsible for many of the buildings and houses built under direction of the Hiram Walker family in Walkerville, Ontario, including Willistead Manor. Kahn's interest in historically styled buildings is also seen in his houses in Detroit's Indian Village, the Cranbrook House, the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House, and The Dearborn Inn, the world's first airport hotel.

Kahn also designed the 28-story Art Deco Fisher Building in Detroit, now a landmark and considered one of the most beautiful elements of the Detroit skyline. In 1928, the Fisher building was honored by the Architectural League of New York as the year's most beautiful commercial structure. Between 1917 and 1929, Kahn designed the headquarters for all three major daily newspapers in Detroit. His work was also part of the architecture event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics.[12]

On May 8, 1929, through an agreement signed with Kahn by President of Amtorg Saul G. Bron, the Soviet government contracted the Albert Kahn firm to design the Stalingrad Tractor Plant, the first tractor plant in the USSR. On January 9, 1930, a second contract with Kahn was signed for his firm to become consulting architects for all industrial construction in the Soviet Union.[13]

Under these contracts, during 1929–1932, Kahn's firm operated from its headquarters in Detroit and the newly established design bureau in Moscow to train and supervise Soviet architects and engineers. The bureau Gosproektstroi was headed by Albert Kahn's younger brother, Moritz Kahn, and 25 Kahn Associates staff were involved in Moscow in this project. They trained more than 4,000 Soviet architects and engineers; and designed 521 plants and factories[6] under the first five-year plan.[13][14]

Kahn also designed many of what are considered the classic buildings at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These include the Burton Memorial Tower, Hill Auditorium, Hatcher Graduate Library, and William L. Clements Library. Kahn said later in life that of all the buildings he designed, he wanted most to be remembered for his work on the William L. Clements Library.

Kahn frequently collaborated with architectural sculptor Corrado Parducci. In all, Parducci worked on about 50 Kahn commissions, including banks, office buildings, newspaper buildings, mausoleums, hospitals, and private residences.

Kahn's firm was able to adapt to the changing needs of World War I and designed numerous army airfield and naval bases for the United States government during the war. By World War II, Kahn's 600-person office was involved in making Detroit industry part of America's Arsenal of Democracy. Among others, the office designed the Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant, and the Willow Run Bomber Plant, Kahn's last building, located in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The Ford Motor Company mass-produced Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers here.[15][16]

In 1937, Albert Kahn Associates was responsible for 19 percent of all architect-designed factories in the U.S.[6] In 1941, Kahn received the eighth highest salary and compensation package in the U.S., $486,936, of which he paid 72% in tax.[17]

Albert Kahn worked on more than 1,000 commissions from Henry Ford[6] and hundreds for other automakers. Kahn designed showrooms for Ford Motor Company in several cities including New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston. He died in Detroit on December 8, 1942.

As of 2006, approximately 60 Kahn buildings were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Not all of Kahn's works have been preserved. Cass Technical High School in Detroit, designed by Malcomson and Higginbotham and built by Albert Kahn's firm in 1922, was demolished in 2011 after vandals had stripped it of most of its fixtures.[18] The Donovan Building, later occupied by Motown Records, was abandoned for decades and deteriorated. The city demolished it as part of its beautification plan before the 2006 Super Bowl XL.

Fifteen Albert Kahn buildings are recognized by official Michigan historical markers:[19]

- Battle Creek Post Office

- The Dearborn Inn

- Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant

- Detroit Free Press Building

- The Detroit News Building

- Detroit Urban League (Albert Kahn House)

- Eastern Liggett School

- Edsel and Eleanor Ford House

- Fisher Building

- Ford Motor Company Lamp Factory

- Grosse Pointe Shores Village Hall

- Highland Park Ford Plant

- Packard Automotive Plant

- Packard Proving Grounds

- Willow Run

He is not related to American architect Louis Kahn of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Kahn-designed buildings

All buildings are located in Detroit, unless otherwise indicated.

- Dexter M. Ferry summer residence, 1890 (remodeling of an early 19th-century stone farmhouse), Unadilla, New York (known as Milfer Farm, held by Ferry heirs today; Kahn also designed the "Honeymoon Cottage" on the estate, one of the earliest prefabricated houses built)

- Hiram Walker offices, 1892, designer for Mason & Rice Windsor, Ontario

- William Livingstone House, 1894 designer for Mason & Rice (demolished, 2007)

- Children's Free Hospital, 1896, Nettleton, Kahn & Trowbridge

- Bethany Memorial Church, 1897, Nettleton, Kahn & Trowbridge

- Bernard Ginsburg House, 1898, Nettleton & Kahn

- Joseph R. McLaughlin, 1899, Nettleton & Kahn

- George Headley, 1900, Nettleton & Kahn

- Edward DeMille Campbell House, 1899, Nettleton & Kahn Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Detroit Racquet Club, 1902 (Kahn designed the building, and the Vinton Company, whose offices were just down Woodbridge Street from the club, was awarded the general contract for erecting the facilities)

- Frederick L. Colby, building permit issued 5/22/1901, finished 1902

- Packard Automotive Plant, 1903 (Kahn's tenth factory built for Packard, but first concrete one)

- Palms Apartments, 1903

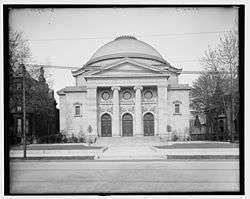

- Temple Beth-El, 1903 (Kahn's home synagogue, now the Bonstelle Theatre of Wayne State University)

- Belle Isle Aquarium and Conservatory, 1904

- Francis C. McMath, building permit issued 8/14/1902 finished 1904

- Brandeis-Millard House, 1904, Gold Coast Historic District, Midtown Omaha, Nebraska

- Arthur Kiefer, building permit issued 5/17/1905, finished 1905

- Charles M. Swift, 1905

- Albert Kahn House, 1906 (his personal residence)

- Burham S. Colburn, building permit issued 8/7/1905, finished 1906

- Gustavus D. Pope, 1906

- Julian C. Madison Building, 1906

- Allen F. Edwards, building permit issued 5/23/1906, finished 1906

- George N. Pierce Plant, 1906, Buffalo, New York

- Willistead Manor, 1906, Windsor, Ontario

- Battle Creek Post Office, 1907, Battle Creek, Michigan (building featuring the concrete construction method used in Kahn's Packard plant)

- Belle Isle Casino, 1907

- Cranbrook House, 1907, Cranbrook Educational Community, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- Service Building for the Packard Motor Car Company, 1907, New York City

- Frederick H. Holt House, 1907[20]

- Highland Park Ford Plant, 1908, Highland Park, Michigan

- Edwin S. George Building, 1908

- Kaufman Footwear Building, 1908, Kitchener, Ontario (renovated into lofts in the early 2000s)

- Mahoning National Bank, 1909, Youngstown, Ohio

- Frederick Stearns Building addition, c. 1910

- Packard Motor Corporation Building, 1910–11, Philadelphia

- Hugh Chalmers, building permit issued 11/6/1909, finished 1911

- Merganthaler Linotype Company Buildings, 1910s-1920s, Brooklyn, New York City

- National Theatre, 1911

- Shaw Walker Company, Five-story expansion, 1912,[21] Muskegon, Michigan

- Bates Mill Building Number 5, 1914, Lewiston, Maine

- Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant, 1914, Cleveland, Ohio (Cleveland Institute of Art since 1981)

- Kales Building, 1914

- Liggett School-Eastern Campus, 1914 (Detroit Waldorf School since 1964)

- Benjamin Siegel, 1913-1914

- Detroit Athletic Club, 1915

- Garden Court Apartments, 1915

- Vinton Building, 1916

- Russell Industrial Center, 1916

- Omaha Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant, 1916, North Omaha, Nebraska

- Ford Motor Company - Assembly Plant, 1916, remodeled in 1924, Oklahoma City, OK

- The Detroit News Building, 1917

- Ford Motor Company New York Headquarters, 1917, New York City

- Ford River Rouge Complex, 1917–28, Dearborn, Michigan

- Multiple buildings and Aircraft Maintenance Hangars (Bldg 777&781), 1917–19, Langley Field, Hampton, Virginia

- Motor Wheel Factory, 1918, Lansing, Michigan (currently being renovated into residential lofts)

- General Motors Building, 1919 (former GM world headquarters and second largest office building in the world at that time)

- Dominion Tire Plant, 1919, Kitchener, Ontario

- Fisher Body Plant 21, 1921

- First Congregational Church addition, 1921

- Phoenix Mill, 1921, Plymouth, Michigan

- First National Building, 1922

- Park Avenue Building, 1922

- Former Detroit Police Headquarters, 1923

- Temple Beth El, 1923 (a new building to replace the 1903 temple, currently occupied by the Bethel Community Transformation Center)

- Walker Power Plant, 1923, Windsor, Ontario

- The Flint Journal Building, 1924, Flint, Michigan

- Olde Building, 1924

- Ford Motor Company Lamp Factory, 1921–25, Flat Rock, Michigan

- Detroit Free Press Building, 1925

- 1001 Covington Apartments, 1925

- Blake Building, 1926, Jackson, Michigan

- Ford Hangar, 1926, Lansing Municipal Airport, Lansing, Illinois

- Packard Motor Car Showroom and Storage Facility, c. 1926, Buffalo, New York

- Packard Proving Grounds, 1926, Shelby Charter Township, Michigan

- Packard Showroom, 1926, New York City

- Consumers Power Company headquarters, 1927, Jackson, Michigan (demolished, 2013)[22]

- S. S. Kresge World Headquarters, 1927

- Edsel and Eleanor Ford House, 1927, Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan

- Fisher Building, 1927

- Muskegon Chronicle Building, 1928, Muskegon, Michigan [23]

- Argonaut Building 1928 (General Motors laboratory, now owned by the College for Creative Studies)

- Brooklyn Printing Plant (New York Times), 1929, Brooklyn, New York City

- Detroit Times Building, 1929 (demolished, 1978)[24]

- Griswold Building, 1929

- Packard Service Building, 1929, New York City

- Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant, 1930, Richmond, California

- New Center Building, 1930 (adjacent to the Fisher Building)

- The Dearborn Inn, 1931, Dearborn, Michigan (world's first airport hotel)

- Former Congregation Shaarey Zedek Building, 1932

- Power Plant, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 1933 [25]

- General Motors Building, 1933, Chicago Century of Progress International Exposition

- Ford Rotunda, 1934, Dearborn, Michigan (designed for the Chicago World's Fair; burned, 1963)

- Chevrolet/Fisher Body plant, Baltimore, Maryland, 1935 (demolished 2006)

- Burroughs Adding Machine Plant, 1938, Plymouth, Michigan

- Dodge Truck Plant, 1938, Warren, Michigan

- Detroit Arsenal Tank Plant, 1941, Warren, Michigan

- Willow Run Bomber Plant, 1941 (used by Ford for bombers during the war, then by Kaiser for cars, then by GM for transmissions)

- Hangars A and B (later renumbered 110 and 111), 1943, NAS Barbers Point, Kapolei, Hawaii

- Upjohn Tower, Kalamazoo, Michigan (designed for the Upjohn Company; demolished after Pfizer buyout, 2005)

- Studebaker Factory, Building 84, 1923, South Bend, Indiana

- Cold Spring Granite Company Main Plant, 1929, Cold Spring, Minnesota (demolished 2008)

- King Edward Public School, 1905, Walkerville Neighbourhood, Windsor, ON. (demolished 1993, original front stone facade saved)

- General Motors Stamping Plant, 1930, Indianapolis, Indiana (demolished 2014)

Buildings at the University of Michigan

Campus structures built during his career (source of this list: Schreiber, Penny. "Albert Kahn's Campus." The Ann Arbor Observer, January, 2002, pp. 27–33):

- Engineering Building (now West Hall), 1904

- Psychopathic Hospital (demolished), 1906

- Hill Auditorium, 1913

- Helen Newberry Residence Hall, 1915

- Natural Science Building, 1915

- Betsy Barbour Residence Hall, 1920

- General Library (now Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library), 1920

- William L. Clements Library, 1923

- Angell Hall, 1924

- Physical Science Building (now Randall Laboratory), 1924

- University Hospital (demolished), 1925

- Couzens Hall, 1925

- East Medical Building (now C. C. Little Building), 1925

- Thomas H. Simpson Memorial Institute, 1927

- Alexander G. Ruthven Museums Building, 1928[26]

- Burton Memorial Tower, 1936

- Neuropsychiatric Institute (demolished), 1938

Greek Organization Buildings:

- Sigma Phi House (1900), 426 North Ingalls Street (demolished)

- Delta Upsilon House (1903), 1331 Hill Street

- Triangle House (1905–06), 1501 Washtenaw Avenue

- Alpha Epsilon Phi House (1912), 1205 Hill Street (formerly Delta Gamma)[27]

- Psi Upsilon House (1924), 1000 Hill Street

See also

- Kahn System, the industrial construction technique developed by Julius Kahn

- Architecture of metropolitan Detroit

- Joseph Nathaniel French

References

- Albert Kahn papers "he also received the Frank P. Brown medal posthumously"

- "Bentley Historical Library Albert Kahn Associates Records 1825-2014".

- "Albert Kahn Research Symposium".

- "Archives of American Art, Albert Kahn Papers".

- "A Golden Age of Jewish Architects" by Abbott Gorin, Jewish Currents, Spring 2015

- Johnson, Donald L. and Donald Langmead (1997). Makers of 20th Century Modern Architecture: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1136640568. Pp. 161-164.

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production, Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1945, pp. 97-100.

- "About Kahn-What". albertkahn.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- Ferry 1970, p. 11.

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production, pp. 107-8, Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis, IN, 1945.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 22, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- "Albert Kahn". Olympedia. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Melnikova-Raich, Sonia (2010). "The Soviet Problem with Two 'Unknowns': How an American Architect and a Soviet Negotiator Jump-Started the Industrialization of Russia, Part I: Albert Kahn". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 36 (2): 59–73. ISSN 0160-1040. JSTOR 41933723.

- "Industry's Architect". Time. June 29, 1942. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

In 1928 the Soviet Government, after combing the U.S. for a man who could furnish the building brains for Russia's industrialization, offered the job to Kahn. Twenty-five Kahn engineers and architects went to Moscow. They had to start from scratch.

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production, pp. 109-10, 120-28, Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis, IN, 1945.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 51-2, 96-8, 148, 200, 227-9, 242, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- "Compensation and the I.R.S.: It's not the 'Good' Old Days". The New York Times. 2010-12-01. (Business Day section). Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- Cass Tech High School (old). Historic Detroit. Retrieved on November 20, 2014.

- "Michigan Historical Markers". Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Benjamin L. Gravel Jr. Frederick H. Holt House (250 East Boston Boulevard). Historic Detroit. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- "Plans at old Shaw Walker site". MLive. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- "Brad Flory column: Good-bye to a landmark once 'the essence of Jackson'". MLive.

- "Chronicle Building now owned by Muskegon Community College". MLive. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- "Detroit Times Building". Buildings of Detroit. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- "New Heating Plant Under Constructio" (PDF). Notre Dame Scholastic magazine: 14. 23 October 1931.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2019-01-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Alpha Epsilon Phi - ΑΕΦ | Greek Life". fsl.umich.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

Further reading

- Bridenstine, James (1989). Edsel and Eleanor Ford House. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2161-5.

- Ferry, W. Hawkins (1970). The Legacy of Albert Kahn. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1889-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fogelman, Randall (2004). Detroit's New Center. Arcadia. ISBN 0-7385-3271-1.

- Lewis, David L. "Ford and Kahn" Michigan History 1980 64(5): 17-28. Ford commissioned architect Albert Kahn to design factories

- Matuz, Roger (2002). Albert Kahn, Builder of Detroit. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2956-6.

- Sobocinski, Melanie Grunow (2005). Detroit and Rome: building on the past. Regents of the University of Michigan. ISBN 0-933691-09-2.

- Melnikova-Raich, Sonia (2010). "The Soviet Problem with Two 'Unknowns': How an American Architect and a Soviet Negotiator Jump-Started the Industrialization of Russia, Part I: Albert Kahn". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 36 (2): 57–80. ISSN 0160-1040. JSTOR 41933723.; Melnikova-Raich, Sonia (2011). "The Soviet Problem with Two 'Unknowns': How an American Architect and a Soviet Negotiator Jump-Started the Industrialization of Russia, Part II: Saul Bron". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 37 (1/2): 5–28. ISSN 0160-1040. JSTOR 23757906. (abstract)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert Kahn. |

- Albert Kahn papers from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Historic Detroit — Albert Kahn

- Albert Kahn papers 1896–2008 Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

- Photos and drawings of The Soviet Diesel Tractor Assembly Plant, Canadian Centre for Architecture

- In Energized Detroit, Savoring an Architectural Legacy — The New York Times, March 26, 2018

- Walkerville

- Albert Kahn Associates

- Edsel and Eleanor Ford House

- Albert Kahn at Find a Grave

- Albert Kahn on LocalWiki