1889 Apia cyclone

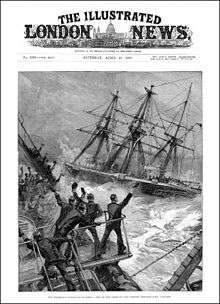

The 1889 Apia cyclone was a tropical cyclone in the South Pacific Ocean, which swept across Apia, Samoa on March 15, 1889, during the Samoan crisis. The effect on shipping in the harbour was devastating, largely because of what has been described as 'an error of judgement that will forever remain a paradox in human psychology'.[1]

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

Apia, Samoa in March 1889, after the cyclone | |

| Formed | before March 13, 1889 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | after March 17, 1889 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 120 km/h (75 mph) |

| Fatalities | 147+ |

| Areas affected | Samoa |

| Part of the Pre-1939 South Pacific cyclone seasons | |

The growing storm

Events ashore had led to upheaval in the Pacific nations and colonies. Both the United States and Imperial Germany saw this as a potential opportunity to expand their holdings in the Pacific through gunboat diplomacy. In order to be ready should such an opportunity arise, both nations had dispatched squadrons to the town to investigate the situation and act accordingly. A British ship was also present, ostensibly to observe the actions of the other nations during the Samoan upheavals.

During the days preceding the cyclone of March 15, increasing signs were visible of the impending disaster. March was cyclone season in this area, and Apia had been hit by a cyclone just three years previously, which the captains of the ships heard about from local people, especially as the weather began to change and the atmospheric pressure began to fall. The captains were experienced Pacific seamen, as were many members of their crews, and they all saw the approaching signs of impending disaster, just as they knew that the only chance they had of riding out the 100 mph (160 km/h) winds was to take to the open sea.

Apia is an exposed harbour, unprotected by high ground or an enclosing reef. The northern part of the harbour is open to the Pacific, and thus wind and waves can sweep through the area and drive any shipping which remained in the bay onto the reefs at the Southern end, or toss them right up the beach. However, even though the officers of the various navies were well aware of the necessary procedures in the face of such a threat, none made a move. This has been attributed to jingoism or national pride; none of the men in the harbour were willing to admit in front of the other nations' navies, that they were afraid of the elements, and so refused to take precautions,[2] and refused to allow the merchant ships which accompanied them to move either, leaving thirteen ships, some larger vessels, at anchor close to one another in Apia harbour.

The cyclone

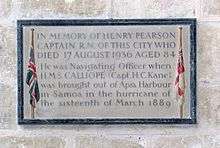

When the cyclone struck the result was catastrophic. The local people had taken themselves to safety well before the storm struck, but the ships in the bay only began to evacuate at the very last minute, and thus were crowding towards the entrance to the bay when the hurricane hit. Only HMS Calliope escaped, making less than one knot against the oncoming wind and sea; she dragged herself to the open sea, despite being less than six feet from a reef at one point. Once out at sea she was easily able to ride out the ensuing winds. Her survival is attributed to her size (2,227 tons) and her more powerful and modern engines, built only five years before, as compared to the ten or twenty years for many of the other ships.

As for the other ships, chaos reigned in the harbour. USS Trenton was tossed against the beach in the afternoon, dragged back into the sea and wrecked on a reef at 10 p.m. that evening, although the majority of her crew survived unhurt and were able to participate in the ensuing rescue operation. USS Vandalia was smashed into the same reef in the early afternoon, and her surviving crew spent a miserable day and night clinging to her rigging before being rescued, by which time 43 of her complement had drowned. USS Nipsic was thrown high on the beach with eight of her crew missing or dead and her internal systems totally wrecked. She would however later be refloated and eventually reconstructed in Hawaii.

The German ships fared much worse: SMS Olga came off best, thrown high onto the beach where she was wrecked but many of her crew survived, escaping onto higher ground. SMS Adler and SMS Eber were less fortunate, because they were caught at the harbour mouth by the initial blow and were bodily picked up and smashed together. Eber sank in deep water, while Adler came to rest on her side, on the reef.[3] In total, 96 men from their crews drowned in the storm, and both ships were totally destroyed. All six of the merchant ships remaining in the harbour were wrecked, and the death toll was well over 200 sailors from several nationalities.[4]

The incident is often cited as a clear example of the dangers of putting national pride before necessity, especially in the face of natural disaster.[5] The incident did not blunt the Pacific ambitions of any of the imperial powers involved in the disaster. However, the Germans and British continued to make territorial gains amongst the Samoan islands and New Guinea, whilst the United States focused on the Philippines and Micronesia, although more care was taken to respect the weather phenomena of the Pacific from this point on.

Ships

| USS Trenton | United States | Wrecked. One dead |

| USS Nipsic | United States | Beached and repaired, 8 dead |

| USS Vandalia | United States | Wrecked, 43 dead |

| HMS Calliope | British | Survived the storm |

| SMS Olga | German | Beached and repaired |

| SMS Eber | German | Wrecked and sunk, 73 dead |

| SMS Adler | German | Wrecked and sunk, 20 dead [6] |

Notes

Some unreferenced and early sources claim that the Olga was a Russian ship, and that the Nipsic was Japanese. This is not true, and is probably caused by those names sounding "ethnic" to an uninformed observer.

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote an account of this disaster, differing from this article in A footnote to history.[7]

References

- Regan, Geoffrey, Naval Blunders

- Regan, Geoffrey (2001). Geoffrey Regan's Book of Naval Blunders. André Deutsch. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-233-99978-7.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-07-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Six War Vessels Sunk; Wrecked in a Hurricane at Samoa" (PDF). The New York Times. 30 March 1889.

- "R.L Stevenson on Samoa" (contemporary book review). The New York Times. 14 August 1892. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- SMS Adler (1883) German Wikipedia article

- Project Gutenberg online text of A Footnote to History, Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa

Further reading

- Andre Trudeau, Noah. "'An Appalling Calamity'-In the teeth of the Great Samoan Typhoon of 1889, a standoff between the German and US navies suddenly didn't matter." Naval History Magazine 25.2 (2011): 54-59.

- Regan, Geoffrey (2001), Naval Blunders, London: Andre Deutch, ISBN 0-233-99978-7.

- Thornton, J. M. (1978), Men-of-War, 1770-1970, Watford: Model and Allied Publications, ISBN 0-85242-610-0.

External links