Flat tax

A flat tax (short for flat-rate tax) is a tax system with a constant marginal rate, usually applied to individual or corporate income. A true flat tax would be a proportional tax, but implementations are often progressive and sometimes regressive depending on deductions and exemptions in the tax base. There are various tax systems that are labeled "flat tax" even though they are significantly different.

Major categories

Flat tax proposals differ in how the subject of the tax is defined.

True flat-rate income tax

A true flat-rate tax is a system of taxation where one tax rate is applied to all personal income with no deductions.

Marginal flat tax

Where deductions are allowed, a 'flat tax' is a progressive tax with the special characteristic that, above the maximum deduction, the marginal rate on all further income is constant. Such a tax is said to be marginally flat above that point. The difference between a true flat tax and a marginally flat tax can be reconciled by recognizing that the latter simply excludes certain types of income from being defined as taxable income; hence, both kinds of tax are flat on taxable income.

Flat tax with limited deductions

Modified flat taxes have been proposed which would allow deductions for a very few items, while still eliminating the vast majority of existing deductions. Charitable deductions and home mortgage interest are the most discussed examples of deductions that would be retained, as these deductions are popular with voters and are often used. Another common theme is a single, large, fixed deduction. This large fixed deduction would compensate for the elimination of various existing deductions and would simplify taxes, having the side-effect that many (mostly low income) households will not have to file tax returns.

Hall–Rabushka flat tax

Designed by economists at the Hoover Institution, Hall–Rabushka is a flat tax on consumption.[1] Principally, Hall–Rabushka accomplishes a consumption tax effect by taxing income and then excluding investment. Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka have consulted extensively in designing the flat tax systems in Eastern Europe.

Negative income tax

The negative income tax (NIT), which Milton Friedman proposed in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, is a type of flat tax. The basic idea is the same as a flat tax with personal deductions, except that when deductions exceed income, the taxable income is allowed to become negative rather than being set to zero. The flat tax rate is then applied to the resulting "negative income," resulting in a "negative income tax" that the government would owe to the household—unlike the usual "positive" income tax, which the household owes the government.

For example, let the flat rate be 20%, and let the deductions be $20,000 per adult and $7,000 per dependent. Under such a system, a family of four making $54,000 a year would owe no tax. A family of four making $74,000 a year would owe tax amounting to 0.20 × (74,000 − 54,000) = $4,000, as would be the case under a flat tax system with deductions. Families of four earning less than $54,000 per year, however, would experience a "negative" amount of tax (that is, the family would receive money from the government instead of paying to the government). For example, if the family earned $34,000 a year, it would receive a check for $4,000. The NIT is intended to replace not just the USA's income tax, but also many benefits low income American households receive, such as food stamps and Medicaid. The NIT is designed to avoid the welfare trap—effective high marginal tax rates arising from the rules reducing benefits as market income rises. An objection to the NIT is that it is welfare without a work requirement. Those who would owe negative tax would be receiving a form of welfare without having to make an effort to obtain employment. Another objection is that the NIT subsidizes industries employing low-cost labor, but this objection can also be made against current systems of benefits for the working poor.

Capped flat tax

A capped flat tax is one in which income is taxed at a flat rate until a specified cap amount is reached. For example, the United States Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax is 6.2% of gross compensation up to a limit (in 2019, up to $132,900 of earnings, for a maximum tax of $8239.80).[2] This cap has the effect of turning a nominally flat tax into a regressive tax.[3]

Requirements for a fully defined schema

In devising a flat tax system, several recurring issues must be enumerated, principally with deductions and the identification of when money is earned.

Defining when income occurs

Since a central tenet of the flat tax is to minimize the compartmentalization of incomes into myriad special or sheltered cases, a vexing problem is deciding when income occurs. This is demonstrated by the taxation of interest income and stock dividends. The shareholders own the company and so the company's profits belong to them. If a company is taxed on its profits, then the funds paid out as dividends have already been taxed. It's a debatable question if they should subsequently be treated as income to the shareholders and thus subject to further tax. A similar issue arises in deciding if interest paid on loans should be deductible from the taxable income since that interest is in-turn taxed as income to the loan provider.[4] There is no universally agreed answer to what is fair. For example, in the United States, dividends are not deductible[5] but mortgage interest is deductible.[6] Thus a Flat Tax proposal is not fully defined until it differentiates new untaxed income from a pass-through of already taxed income.

Policy administration

Taxes, in addition to providing revenue, can be potent instruments of policy. For example, it is common for governments to encourage social policy such as home insulation or low income housing with tax credits rather than constituting a ministry to implement these policies.[7] In a flat tax system with limited deductions such policy administration, mechanisms are curtailed. In addition to social policy, flat taxes can remove tools for adjusting economic policy as well. For example, in the United States, short-term capital gains are taxed at a higher rate than long-term gains as means to promote long-term investment horizons and damp speculative fluctuation.[8] Thus, if one assumes that government should be active in policy decisions such as this, then claims that flat taxes are cheaper/simpler to administer than others are incomplete until they factor in costs for alternative policy administration.

Minimizing deductions

In general, the question of how to eliminate deductions is fundamental to the flat tax design; deductions dramatically affect the effective "flatness" in the tax rate. Perhaps the single biggest necessary deduction is for business expenses. If businesses were not allowed to deduct expenses, businesses with a profit margin below the flat tax rate could never earn any money since the tax on revenues would always exceed the earnings. For example, grocery stores typically earn pennies on every dollar of revenue; they could not pay a tax rate of 25% on revenues unless their markup exceeded 25%. Thus, corporations must be able to deduct operating expenses even if individual citizens cannot. A practical dilemma now arises as to identifying what is an expense for a business.[9] For example, if a peanut butter producer purchases a jar manufacturer, is that an expense (since they have to purchase jars somehow) or a sheltering of their income through investment? Flat tax systems can differ greatly in how they accommodate such gray areas. For example, the "9-9-9" flat tax proposal would allow businesses to deduct purchases but not labor costs.[10] (This effectively taxes labor-intensive industrial revenue at a higher rate.[11]) How deductions are implemented will dramatically change the effective total tax, and thus the flatness of the tax.[4] Thus, a flat tax proposal is not fully defined unless the proposal includes a differentiation between deductible and non-deductible expenses.

Tax effects

Diminishing marginal utility

Flat tax benefits higher income brackets progressively due to decline in marginal value.[12] For example, if a flat tax system has a large per-citizen deductible (such as the "Armey" scheme below), then it is a progressive tax. As a result, the term Flat Tax is actually a shorthand for the more proper marginally flat tax.[4]

Administration and enforcement

One type of flat tax would be imposed on all income once; at the source of the income. Hall and Rabushka (1995) includes a proposed amendment to the U.S. Internal Revenue Code that would implement the variant of the flat tax they advocate.[13] This amendment, only a few pages long, would replace hundreds of pages of statutory language (although most statutory language in taxation statutes is not directed at specifying graduated tax rates).

As it now stands, the U.S. Internal Revenue Code is over several million words long, and contains many loopholes, deductions, and exemptions which, advocates of flat taxes claim, render the collection of taxes and the enforcement of tax law complicated and inefficient.

It is further argued that current tax law slows economic growth by distorting economic incentives, and by allowing, even encouraging, tax avoidance. With a flat tax, there are fewer incentives than in the current system to create tax shelters, and to engage in other forms of tax avoidance.

Flat tax critics contend that a flat tax system could be created with many loopholes, or a progressive tax system without loopholes, and that a progressive tax system could be as simple, or simpler, than a flat tax system. A simple progressive tax would also discourage tax avoidance.

Under a pure flat tax without deductions, every tax period a company would make a single payment to the government covering the taxes on the employees and the taxes on the company profit.[14] For example, suppose that in a given year, a company called ACME earns a profit of 3 million, spends 2 million in wages, and spends 1 million on other expenses that under the tax law is taxable income to recipients, such as the receipt of stock options, bonuses, and certain executive privileges. Given a flat rate of 15%, ACME would then owe the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) (3M + 2M + 1M) × 0.15 = 900,000. This payment would, in one fell swoop, settle the tax liabilities of ACME's employees as well as the corporate taxes owed by ACME. Most employees throughout the economy would never need to interact with the IRS, as all tax owed on wages, interest, dividends, royalties, etc. would be withheld at the source. The main exceptions would be employees with incomes from personal ventures. The Economist claims that such a system would reduce the number of entities required to file returns from about 130 million individuals, households, and businesses, as at present, to a mere 8 million businesses and self-employed.[15]

However, this simplicity depends on the absence of deductions of any kind being allowed (or at least no variability in the deductions of different people). Furthermore, if income of differing types are segregated (e.g., pass-through, long term cap gains, regular income, etc.) then complications ensue. For example, if realized capital gains were subject to the flat tax, the law would require brokers and mutual funds to calculate the realized capital gain on all sales and redemption. If there were a gain, a tax equal to 15% of the amount of the gain would be withheld and sent to the IRS. If there were a loss, the amount would be reported to the IRS. The loss would offset gains, and then the IRS would settle up with taxpayers at the end of the period. Lacking deductions, this scheme cannot be used to implement economic and social policy indirectly by tax credits and thus, as noted above, the simplifications to the government's revenue collection apparatus might be offset by new government ministries required to administer those policies.

Revenues

The Russian Federation is considered a prime case of the success of a flat tax; the real revenues from its Personal Income Tax rose by 25.2% in the first year after the Federation introduced a flat tax, followed by a 24.6% increase in the second year, and a 15.2% increase in the third year.[16]

The Russian example is often used as proof of the validity of this analysis, despite an International Monetary Fund study in 2006 which found that there was no sign "of Laffer-type behavioral responses generating revenue increases from the tax cut elements of these reforms" in Russia or in other countries.[17]

Overall structure

Taxes other than the income tax (for example, taxes on sales and payrolls) tend to be regressive. Hence, making the income tax flat could result in a regressive overall tax structure. Under such a structure, those with lower incomes tend to pay a higher proportion of their income in total taxes than the affluent do. The fraction of household income that is a return to capital (dividends, interest, royalties, profits of unincorporated businesses) is positively correlated with total household income. Hence a flat tax limited to wages would seem to leave the wealthy better off. Modifying the tax base can change the effects. A flat tax could be targeted at income (rather than wages), which could place the tax burden equally on all earners, including those who earn income primarily from returns on investment. Tax systems could utilize a flat sales tax to target all consumption, which can be modified with rebates or exemptions to remove regressive effects (such as the proposed Fair Tax in the U.S.[18]).

Border adjustable

A flat tax system and income taxes overall are not inherently border-adjustable; meaning the tax component embedded into products via taxes imposed on companies (including corporate taxes and payroll taxes) are not removed when exported to a foreign country (see Effect of taxes and subsidies on price). Taxation systems such as a sales tax or value added tax can remove the tax component when goods are exported and apply the tax component on imports. The domestic products could be at a disadvantage to foreign products (at home and abroad) that are border-adjustable, which would impact the global competitiveness of a country. However, it's possible that a flat tax system could be combined with tariffs and credits to act as border adjustments (the proposed Border Tax Equity Act in the U.S. attempts this). Implementing an income tax with a border adjustment tax credit is a violation of the World Trade Organization agreement. Tax exemptions (allowances) on low income wages, a component of most income tax systems could mitigate this issue for high labour content industries like textiles that compete Globally.

In a subsequent section, various proposals for flat tax-like schemes are discussed, these differ mainly on how they approach with the following issues of deductions, defining income, and policy implementation.

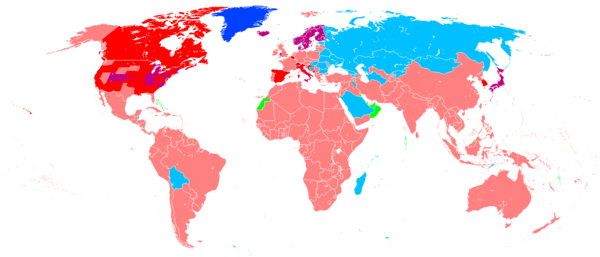

Around the world

Most countries tax personal income at the national level using progressive rates, but some use a flat rate. Most countries that have or had a flat tax on personal income at the national level are former communist countries or islands.

In some countries, subdivisions are allowed to tax personal income in addition to the national government. Many of these subdivisions use a flat rate, even if their national government uses progressive rates. Examples are all counties and municipalities of the Nordic countries, all prefectures and municipalities of Japan, and some subdivisions of Italy and of the United States.

Jurisdictions that have a flat tax on personal income

The table below lists jurisdictions where the personal income tax imposed by all levels of government is a flat rate. It includes independent countries and other autonomous jurisdictions. The tax rate listed is the one that applies to income from work, but does not include mandatory contributions to social security. In some jurisdictions, different rates (also flat) apply to other types of income, such as from investments.

|

Personal income taxed by:

None

One government level, at a flat rate

One government level, at progressive rates

Multiple government levels, at a flat rate

Multiple government levels, at progressive rates

Multiple government levels, some at a flat rate and some at progressive rates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subnational jurisdictions

The table below lists subnational jurisdictions that tax personal income at a flat rate, in addition to the progressive rates used by their national government. The tax rates listed are those that apply to income from work, except as otherwise noted. Where a range of rates is listed, it means that the flat rate varies by location, not progressive rates.

|

|

Jurisdictions without permanent population

Despite not having a permanent population, some jurisdictions tax the local income of temporary workers, using a flat rate.

|

Jurisdictions reputed to have a flat tax

Jurisdictions that had a flat tax

Subnational jurisdictions

See also

Economic Concepts

- Excess burden of taxation (or more broadly deadweight loss)

- Fiscal drag (also known as Bracket creep)

- Taxable income elasticity (also known as Laffer Curve)

Tax Systems

Notes

- Hoover Institution – Books – The Flat Tax Archived 23 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- OASDI and SSI Program Rates & Limits Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, United States Social Security Administration.

- Are Payroll Taxes Regressive Archived 4 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Economist.

- See for example the flat tax resources at idebate.org

- "When Is a Dividend Deductible?". CFO. 18 September 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- "Publication 936 (2014), Home Mortgage Interest Deduction". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- For example the ENERGYSTAR Archived 2 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine tax credit

- As a recent example, transaction costs to damp speculation proposed by James Tobin, winner of the 1972 Nobel prize in economics, were recently (2009) proposed to the G20 by British PM Gordon brown as a way to prevent international currency speculation. Krugman Archived 24 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Corporations | Internal Revenue Service". www.irs.gov. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Herman Cain's 9-9-9 flat tax variation Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- E.D> Kleinbart, An analysis of Herman Cain's 999 plan, Social Science Research Center, 2011 Archived 15 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- The diminishing marginal utility means that the number of units of additional 'happiness' afforded by an extra unit of additional money, decreases as one spends more money. Archived 30 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Hall, Robert; Rabushka, Alvin (2007). "Appendix: A Flat-Tax Law" (PDF). The Flat Tax (2nd ed.). Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817993115. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "The flat-tax revolution". The Economist. 14 April 2005. Archived from the original on 20 December 2005. Retrieved 28 October 2005.

- "The case for flat taxes". The Economist. 14 April 2005. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Three Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, Hoover Institution Public Policy Inquiry, www.russianeconomy.org, 26 April 2004

- "The "Flat Tax(es)": Principles and Evidence" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- Boortz, Neal; Linder, John (2006). The Fair Tax Book (Paperback ed.). Regan Books. ISBN 0-06-087549-6.

- Law on the income tax on individuals Archived 12 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the Republic of Abkhazia. (in Russian)

- Armenia introduces flat income tax – wealthy rejoice, experts concerned, JAMnews, 8 January 2020.

- Guide to investment Archived 3 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Artsakh Investment Fund, 2016.

- Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration Guide 2019–20, Ernst & Young, November 2019.

- "Income and business tax act chapter 55" (PDF). Income Tax Department of Belize. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina tax system Archived 25 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Investment Promotion Agency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 26 January 2016.

- Annual income tax return Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Timor-Leste Ministry of Finance.

- Set percentages for the 2020 income year, Tax Agency of Greenland, 4 December 2019.(in Greenlandic and Danish)

- The Direct Taxes for 2020 (Sark) Ordinance, 2019, Guernsey Legal Resources.

- Iraq Highlights 2020, Deloitte, April 2020.

- Kyrgyzstan highlights 2018 Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte.

- "Law on the income tax on individuals" (in Russian). Committee on Taxes and Duties of the Republic of South Ossetia. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- A Low Flat Tax Has Been Adopted in Pridnestrovie Archived 10 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 17 August 2007.

- Turkmenistan highlights 2019 Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte.

- Local government personal taxation by time, region and tax rate, Statistics Denmark.

- Residents of Danish island cannot vote, DR, 21 November 2017.(in Danish)

- Table of municipal tax, church tax and child deduction 2020, TAKS. (in Faroese)

- List of municipal and church income tax rates in year 2020, Tax Administration of Finland, 27 November 2019. (in Finnish)

- Municipal tax rates, Icelandic Association of Local Authorities. (in Icelandic)

- Regional additional to the personal income tax, Department of Finance of Italy, 2020. (in Italian)

- Municipal additional to the personal income tax, Department of Finance of Italy, 2020. (in Italian)

- Overview of individual tax system, Japan External Trade Organization.

- Other personal tax, Department of Finance of Norway, 27 September 2019. (in Norwegian)

- Jan Mayen and the Norwegian dependencies in Antarctica, Norwegian Tax Administration. (in Norwegian)

- Local tax rates 2020, by municipality, Statistics Sweden, 17 January 2020.

- Tax bases 2001–2020, Canton of Obwalden, 6 January 2020. (in German)

- Ordinary taxes 2012–2020, Canton of Uri, 19 December 2019. (in German)

- Welsh Rates of Income Tax, Welsh Government, 3 March 2020.

- Income Tax in Scotland, Gov.uk.

- Welsh Rates of Income Tax 2020–2021, Welsh Parliament, 3 March 2020.

- Alabama, TimeTrex, January 2020.

- Occupational Tax Return, Avenu, November 2019.

- Occupational tax reporting, City of Tuskegee.

- Individual income tax, Colorado General Assembly.

- Earned income tax regulations, City of Wilmington, February 2011.

- Income Tax Rates, Illinois Department of Revenue.

- How to compute withholding for state and county income tax, Department of Revenue of Indiana, 1 January 2020.

- Local intangibles tax return 2020, Kansas Department of Revenue.

- Individual Income Tax, Kentucky Department of Revenue.

- Rates, Kenton County.

- Tax Administrator, Mercer County.

- Important Documents, Cumberland County.

- City Occupational Tax Rates, Kentucky League of Cities, 21 October 2019.

- Taxes, Kentucky Department of Education, 16 March 2020.

- Occupational Tax Forms, Montgomery County.

- Form W1 instructions, Louisville-Jefferson County Metro Government.

- Tax Rates, Comptroller of Maryland.

- Personal income tax for residents, Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- What are the current tax rate and exemption amounts?, Michigan Department of Treasury.

- What cities impose an income tax?, Michigan Department of Treasury.

- Have you paid your KCMO earnings tax?, Kansas City, Missouri.

- Earnings tax, City of Saint Louis.

- Overview of New Hampshire taxes, Department of Revenue Administration of New Hampshire.

- Tax rate for tax year 2019, North Carolina Department of Revenue.

- Municipal Income Tax Rate Database, The Finder.

- School District Income Tax Rate Database, The Finder.

- Personal income tax, Pennsylvania Department of Revenue.

- EIT / PIT / LST Tax Registers, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, 15 June 2020.

- Due date and tax rates, Department of Revenue of Tennessee.

- Tax rates, Utah State Tax Commission.

- Frequently Asked Questions about BAT Tax, British Antarctic Survey, September 2014.

- Practical guide of the winter sojourner in the French Southern Lands, French Southern and Antarctic Lands, September 2019. (in French)

- Guide to the Income Tax Ordinance, Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, 30 January 2017.

- Anguilla Highlights 2018 Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte.

- Interim Stabilisation Levy Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Inland Revenue Department of Anguilla.

- Social Security Contributions Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Anguilla Social Security Board.

- British Virgin Islands Highlights 2018 Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte.

- Payroll Tax Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Government of the British Virgin Islands.

- Registration and contribution Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, British Virgin Islands Social Security Board.

- National Health Insurance Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, British Virgin Islands National Health Insurance.

- Daniel Mitchell. "Fixing a Broken Tax System with a Flat Tax." Capitalism Magazine, 23 April 2004. Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "GovHK: Tax Rates of Salaries Tax & Personal Assessment". 24 June 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Hong Kong Highlights 2015 Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte.

- Duncan B. Black. "Fund wrong on Hong Kong 'flat tax'." Media Matters, 28 February 2005. Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Alan Reynolds. "Hong Kong's Excellent Taxes." townhall.com, but the column was syndicated. 6 June 2005. Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration Guide 2017-18 Archived 29 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Ernst & Young, September 2017.

- The Flat Tax at Work in Albania: Year One Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 21 January 2009.

- Albania Abandons Its Flat Tax Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 29 December 2013.

- Flat tax roundup December 2012 Archived 17 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 29 December 2012.

- Income Tax (Amendment) Order, 2014, Grenada Inland Revenue Division.

- Income Tax (Amendment) Act 2017 Archived 9 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Parliament of Guyana.

- Iceland Comes in From the Cold With Flat Tax Revolution Archived 28 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Business, 21 March 2007.

- Iceland abandons the flat tax Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 16 March 2010.

- Income tax rates, thresholds and exemptions 2003-2018 Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Tax Administration Jamaica.

- Flat tax reforms Archived 16 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 4liberty.eu, 6 March 2013.

- Janis Grasis and Juris Bojārs, "Necessity of the introduction of the progressive income tax system: A case of Latvia", Economics, Social Sciences and Information Management, March 2015.

- Latvian parliament adopts tax reform Archived 16 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Tax-News, 3 August 2017.

- OECD tax database explanatory annex, OECD, April 2019.

- Alvin Rabushka. "Flat and Flatter Taxes Continue to Spread Around the Globe." 16 January 2007."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Income Tax - Pay As You Earn (PAYE) Archived 15 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Mauritius Revenue Authority, 1 August 2017.

- Income Tax - Pay As You Earn (PAYE) Archived 24 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Mauritius Revenue Authority, 3 August 2018.

- The Flat Tax Spreads to Montenegro Archived 14 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 13 April 2007.

- Montenegro: Crisis tax Archived 6 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, International Tax Review, 25 March 2015.

- Crisis tax also in 2016; the tax rate decreased to 11% Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Cafe del Montenegro, 14 November 2015.

- "The lowest flat corporate and personal income tax rates." Invest Macedonia government web site. Retrieved 6 June 2007. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Macedonia: Changes in the tax legislation Archived 7 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Lexology, 28 December 2018.

- St. Helena Adopts a 25% Flat Tax Archived 13 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Alvin Rabushka, 3 November 2013.

- Income Tax Ordinance Archived 19 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Saint Helena.

- Trinidad & Tobago's recent tax changes and regulations Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Business Group.

- Income Tax Act 1992 Archived 10 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute.

- Income Tax (Amendment) Act 2008 Archived 18 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Tuvalu Legislation.

- The winners and losers if Alberta returns to a flat tax system, Maclean's, 9 May 2018.

References

- Steve Forbes, 2005. Flat Tax Revolution. Washington: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-040-9

- Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka, 1995 (1985). The Flat Tax. Hoover Institution Press.

- Richard Parncutt, 2006–2010. Free enterprise without poverty: Effectively progressive income tax..

- Anthony J. Evans, "Ideas and Interests: The Flat Tax" Open Republic 1(1), 2005

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Taxation |

- The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future: A detailed examination of the theory behind the Laffer curve, and many case studies of tax cuts on government revenue in the United States

- Podcast of Rabushka discussing the flat tax Alvin Rabushka discusses the flat tax with Russ Roberts on EconTalk.

- Podcast of Rabushka discussing the flat tax Alvin Rabushka discusses the flat tax on PoliTalk.

- The Flat Tax: How it Works and Why it is Good for America