Medicaid

Medicaid in the United States is a federal and state program that helps with medical costs for some people with limited income and resources. Medicaid also offers benefits not normally covered by Medicare, including nursing home care and personal care services. The Health Insurance Association of America describes Medicaid as "a government insurance program for persons of all ages whose income and resources are insufficient to pay for health care."[1] Medicaid is the largest source of funding for medical and health-related services for people with low income in the United States, providing free health insurance to 74 million low-income and disabled people (23% of Americans) as of 2017.[2][3][4] It is a means-tested program that is jointly funded by the state and federal governments and managed by the states,[5] with each state currently having broad leeway to determine who is eligible for its implementation of the program. States are not required to participate in the program, although all have since 1982. Medicaid recipients must be U.S. citizens or qualified non-citizens, and may include low-income adults, their children, and people with certain disabilities.[6] Poverty alone does not necessarily qualify someone for Medicaid.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) significantly expanded both eligibility for and federal funding of Medicaid. Under the law as written, all U.S. citizens and qualified non-citizens with income up to 133% of the poverty line, including adults without dependent children, would qualify for coverage in any state that participated in the Medicaid program. However, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius that states do not have to agree to this expansion in order to continue to receive previously established levels of Medicaid funding, and some states have chosen to continue with pre-ACA funding levels and eligibility standards.[7]

Research suggests that Medicaid improves health insurance coverage, access to health care, recipients' financial security, and some health outcomes, as well as economic benefits to states and health providers.[2][8]

Medicaid, Medicare, Tricare, and ChampVA are the four government sponsored medical insurance programs in the United States and the former two are administered by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in Baltimore, Maryland.[9]

Features

Beginning in the 1980s, many states received waivers from the federal government to create Medicaid managed care programs. Under managed care, Medicaid recipients are enrolled in a private health plan, which receives a fixed monthly premium from the state. The health plan is then responsible for providing for all or most of the recipient's healthcare needs. Today, all but a few states use managed care to provide coverage to a significant proportion of Medicaid enrollees. As of 2014, 26 states have contracts with managed care organizations (MCOs) to deliver long-term care for the elderly and individuals with disabilities. The states pay a monthly capitated rate per member to the MCOs that provide comprehensive care and accept the risk of managing total costs.[10] Nationwide, roughly 80% of enrollees are enrolled in managed care plans.[11] Core eligibility groups of poor children and parents are most likely to be enrolled in managed care, while the aged and disabled eligibility groups more often remain in traditional "fee for service" Medicaid.

Because the service level costs vary depending on the care and needs of the enrolled, a cost per person average is only a rough measure of actual cost of care. The annual cost of care will vary state to state depending on state approved Medicaid benefits, as well as the state specific care costs. 2008 average cost per senior was reported as $14,780 (in addition to Medicare), and a state by state listing was provided. In a 2010 national report for all age groups, the per enrolled average cost was calculated to $5,563 and a listing by state and by coverage age is provided.[12]

History

The Social Security Amendments of 1965 created Medicaid by adding Title XIX to the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396 et seq. Under the program, the federal government provides matching funds to states to enable them to provide medical assistance to residents who meet certain eligibility requirements. The objective is to help states provide medical assistance to residents whose incomes and resources are insufficient to meet the costs of necessary medical services. Medicaid serves as the nation's primary source of health insurance coverage for low-income populations.

States are not required to participate. Those that do must comply with federal Medicaid laws under which each participating state administers its own Medicaid program, establishes eligibility standards, determines the scope and types of services it will cover, and sets the rate of payment. Benefits vary from state to state, and because someone qualifies for Medicaid in one state, it does not mean they will qualify in another.[13] The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) monitors the state-run programs and establishes requirements for service delivery, quality, funding, and eligibility standards.

The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program and the Health Insurance Premium Payment Program (HIPP) were created by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA-90). This act helped to add Section 1927 to the Social Security Act of 1935 which became effective on January 1, 1991. This program was formed due to the costs that Medicaid programs were paying for outpatient drugs at their discounted prices.[14]

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (OBRA-93) amended Section 1927 of the Act as it brought changes to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program,[14] as well as requiring states to implement a Medicaid estate recovery program to sue the estate of decedents for long-term-care-related costs paid by Medicaid, and giving states the option of recovering all non-long-term-care costs, including full medical costs.[15] (Estate recovery, when the state recovers all medical costs for people 55 and older, extends to the expanded Medicaid coverage that is part of the ACA.)

Medicaid also offers a Fee for Service (Direct Service) Program to schools throughout the United States for the reimbursement of costs associated with the services delivered to special education students.[16] Federal law mandates that every disabled child in America receive a "free appropriate public education." Decisions by the United States Supreme Court and subsequent changes in federal law make it clear that Medicaid must pay for services provided for all Medicaid-eligible disabled children.

Expansion under the Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, would have revised and expanded Medicaid eligibility starting in 2014. Under the law as written, states that wished to participate in the Medicaid program would be required to allow people with income up to 133% of the poverty line to qualify for coverage, including adults without dependent children. The federal government would pay 100% of the cost of Medicaid eligibility expansion in 2014, 2015, and 2016; 95% in 2017, 94% in 2018, 93% in 2019, and 90% in 2020 and all subsequent years.[17]

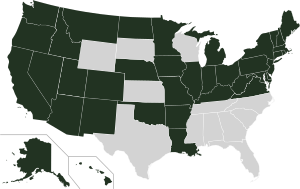

However, the Supreme Court ruled in NFIB v. Sebelius that this provision of the ACA was coercive, and that the federal government must allow states to continue at pre-ACA levels of funding and eligibility if they chose. Several states have opted to reject the expanded Medicaid coverage provided for by the act; over half of the nation's uninsured live in those states. They include Texas, Florida, Kansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi.[18] As of May 24, 2013 a number of states had not made final decisions, and lists of states which have opted out or were considering opting out varied,[19][20] but Alaska,[20] Idaho,[21] South Dakota,[21] Nebraska,[19] Wisconsin,[21] Maine,[21] North Carolina,[21] South Carolina,[21] and Oklahoma[21] seemed to have decided to reject expanded coverage.[21]

Several factors are associated with states' decisions to accept or reject Medicaid expansion in accordance with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Partisan composition of state governments is the most significant factor, with states led primarily by Democrats tending to expand Medicaid and states led primarily by Republicans tending to reject expansion.[22] Other important factors include the generosity of the Medicaid program in a given state prior to 2010, spending on elections by health care providers, and the attitudes people in a given state tend to have about the role of government and the perceived beneficiaries of expansion.[23][24]

The federal government will pay 100% of defined costs for certain newly eligible adult Medicaid beneficiaries in "Medicaid Expansion" states.[25][26] The NFIB v. Sebelius ruling, effective January 1, 2014, allows Non-Expansion states to retain the program as it was before January 2014.

As of January 2014, 20 states confirmed opting out, including Alabama, Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia & Wisconsin. States opting in after 2014 are Indiana & Pennsylvania.[27] On July 17, 2015, Governor Bill Walker sent a letter to the Alaskan state legislature, providing the required 45-day notice of his intention to accept the expansion of Medicaid in Alaska.[28] In November 2018, voters in Nebraska, Utah and Idaho approved ballot measures to expand Medicaid.[29] In June 2020, voters in Oklahoma approved a ballot measure to expand Medicaid as well[30]; voters in Missouri did the same in August 2020[31]. As of August 2020, confirmed opting out states have shrunk to 12 states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Under 2017 American Health Care Act (AHCA) legislation under the House and Senate, both versions of proposed Republican bills had proposed cuts to Medicaid funding on differing timelines. Under both bills, the Congressional Budget Office rated these as Medicaid coverage reductions, with the Senate bill reducing the costs of Medicaid by 26% by the year 2026, in comparison to projections of ACA subsidies. Additionally, CBO estimates predicted the number of uninsured rising under AHCA from 28 million persons to 49 million (under the Senate bill) or to 51 (under the House Bill).[32] The bill was ultimately not passed.

State implementations

States may bundle together the administration of Medicaid with other programs such as the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), so the same organization that handles Medicaid in a state may also manage the additional programs. Separate programs may also exist in some localities that are funded by the states or their political subdivisions to provide health coverage for indigents and minors.

State participation in Medicaid is voluntary; however, all states have participated since 1982 when Arizona formed its Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS) program. In some states Medicaid is subcontracted to private health insurance companies, while other states pay providers (i.e., doctors, clinics and hospitals) directly. There are many services that can fall under Medicaid and some states support more services than other states. The most provided services are intermediate care for mentally handicapped, prescription drugs and nursing facility care for under 21-year-olds. The least provided services include institutional religious (non-medical) health care, respiratory care for ventilator dependent and PACE (inclusive elderly care).[33]

Most states administer Medicaid through their own programs. A few of those programs are listed below:

- Arizona: AHCCCS

- California: Medi-Cal

- Connecticut: HUSKY D

- Maine: MaineCare

- Massachusetts: MassHealth

- New Jersey: NJ FamilyCare

- Oregon: Oregon Health Plan

- Oklahoma: Soonercare

- Tennessee: TennCare

- Washington Apple Health

- Wisconsin: BadgerCare

As of January 2012, Medicaid and/or CHIP funds could be obtained to help pay employer health care premiums in Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, and Georgia.[34]

Differences by state

Medicaid is managed by the states, and each one has varying criteria on how to qualify for the program, what services are covered, and how physicians and care providers are reimbursed through the program. Differences between states are often influenced by the political ideologies of the state and cultural beliefs of the general population.

Medicaid estate recovery regulations also vary by state. (Federal law gives options as to whether non-long-term-care-related expenses, such as normal health-insurance-type medical expenses are to be recovered, as well as on whether the recovery is limited to probate estates or extends beyond.)[15]

Political influences

Several political factors influence the cost and eligibility of tax-funded health care, according to a study conducted by Gideon Lukens,[35] which found salient factors affecting eligibility included "party control, the ideology of state citizens, the prevalence of women in legislatures, the line-item veto, and physician interest group size," and which supported the generalized hypothesis that Democrats favor generous eligibility policies, while Republicans do not. When the Supreme Court allowed states to decide whether to expand Medicaid or not in 2012, northern states, in which Democrat legislators predominated, disproportionately did so, often also extending existing eligibility. Certain states in which there is a Republican-controlled legislature may be forced to expand Medicaid in ways extending beyond increasing existing eligibility in the form of waivers for certain Medicaid requirements so long as they follow certain objectives. In its implementation, this has meant using Medicaid funds to pay for low-income citizens’ health insurance; this private-option was originally carried out in Arkansas but was adopted by other Republican-led states.[36] However, private coverage is more expensive than Medicaid and the states would not have to contribute as much to the cost of private coverage.[37]

Certain groups of people, such as migrants, face more barriers to health care than others due to factors besides policy, which can still be very challenging, such as status, transportation and knowledge of the healthcare system (including eligibility).[38]

Eligibility and coverage

Medicaid eligibility policies are very complicated. In general, a person's Medicaid eligibility is linked to their eligibility for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which provides aid to children whose families have low or no income, and to the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program for the aged, blind and disabled. States are required under federal law to provide all AFDC and SSI recipients with Medicaid coverage. Because eligibility for AFDC and SSI essentially guarantees Medicaid coverage, examining eligibility/coverage differences per state in AFDC and SSI is an accurate way to assess Medicaid differences as well. SSI coverage is largely consistent by state, and requirements on how to qualify or what benefits are provided are standard. However AFDC has differing eligibility standards that depend on:

- The Low-Income Wage Rate: State welfare programs base the level of assistance they provide on some concept of what is minimally necessary.

- Perceived Incentive for Welfare Migration. Not only do social norms within the state affect its determination of AFDC payment levels, but regional norms will affect a state's perception of need as well.

- Racism. Empirical studies have found that specific demographic characteristics of AFDC recipients also affect voters' perceptions of the appropriate AFDC payment level

Reimbursement for care providers

Beyond the variance in eligibility and coverage between states, there is a large variance in the reimbursements Medicaid offers to care providers; the clearest examples of this are common orthopedic procedures. For instance, in 2013, the average difference in reimbursement for 10 common orthopedic procedures in the states of New Jersey and Delaware was $3,047.[39] The discrepancy in the reimbursements Medicaid offers may affect the type of care provided to patients.

Enrollment

According to CMS, the Medicaid program provided health care services to more than 46.0 million people in 2001.[40][5] In 2002, Medicaid enrollees numbered 39.9 million Americans, the largest group being children[41] (18.4 million or 46%). From 2000 to 2012, the proportion of hospital stays for children paid by Medicaid increased by 33%, and the proportion paid by private insurance decreased by 21%.[42] Some 43 million Americans were enrolled in 2004 (19.7 million of them children) at a total cost of $295 billion. In 2008, Medicaid provided health coverage and services to approximately 49 million low-income children, pregnant women, elderly people, and disabled people. In 2009, 62.9 million Americans were enrolled in Medicaid for at least one month, with an average enrollment of 50.1 million.[43] In California, about 23% of the population was enrolled in Medi-Cal for at least 1 month in 2009–10.[44]

Medicaid payments currently assist nearly 60% of all nursing home residents and about 37% of all childbirths in the United States. The federal government pays on average 57% of Medicaid expenses.

Loss of income and medical insurance coverage during the 2008–2009 recession resulted in a substantial increase in Medicaid enrollment in 2009. Nine U.S. states showed an increase in enrollment of 15% or more, resulting in heavy pressure on state budgets.[45]

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported that for 2013, Medicaid recipients were 40% white, 21% black, 25% Hispanic, and 14% other races.[46]

Comparisons with Medicare

Unlike Medicaid, Medicare is a social insurance program funded at the federal level[47] and focuses primarily on the older population. As stated in the CMS website,[5] Medicare is a health insurance program for people age 65 or older, people under age 65 with certain disabilities, and (through the End Stage Renal Disease Program) people of all ages with end-stage renal disease. The Medicare Program provides a Medicare part A which covers hospital bills, Medicare Part B which covers medical insurance coverage, and Medicare Part D which covers prescription drugs.

Medicaid is a program that is not solely funded at the federal level. States provide up to half of the funding for Medicaid. In some states, counties also contribute funds. Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is a means-tested, needs-based social welfare or social protection program rather than a social insurance program. Eligibility is determined largely by income. The main criterion for Medicaid eligibility is limited income and financial resources, a criterion which plays no role in determining Medicare coverage. Medicaid covers a wider range of health care services than Medicare.

Some people are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare and are known as Medicare dual eligible or medi-medi's.[48][49] In 2001, about 6.5 million people were enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. In 2013, approximately 9 million people qualified for Medicare and Medicaid.[50]

Benefits

There are two general types of Medicaid coverage. "Community Medicaid" helps people who have little or no medical insurance. Medicaid nursing home coverage pays all of the costs of nursing homes for those who are eligible except that the recipient pays most of his/her income toward the nursing home costs, usually keeping only $66.00 a month for expenses other than the nursing home.

Some states operate a program known as the Health Insurance Premium Payment Program (HIPP). This program allows a Medicaid recipient to have private health insurance paid for by Medicaid. As of 2008 relatively few states had premium assistance programs and enrollment was relatively low. Interest in this approach remained high, however.[51]

Included in the Social Security program under Medicaid are dental services. They are optional for people older than 21 years but required for people eligible for Medicaid and younger than 21.[52] Minimum services include pain relief, restoration of teeth and maintenance for dental health. Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) is a mandatory Medicaid program for children that focuses on prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions.[52] Oral screenings are not required for EPSDT recipients, and they do not suffice as a direct dental referral. If a condition requiring treatment is discovered during an oral screening, the state is responsible for paying for this service, regardless of whether or not it is covered on that particular Medicaid plan.[53]

Dental

Children enrolled in Medicaid are individually entitled under the law to comprehensive preventive and restorative dental services, but dental care utilization for this population is low. The reasons for low use are many, but a lack of dental providers who participate in Medicaid is a key factor.[54][55] Few dentists participate in Medicaid – less than half of all active private dentists in some areas.[56] Cited reasons for not participating are low reimbursement rates, complex forms and burdensome administrative requirements.[57][58] In Washington state, a program called Access to Baby and Child Dentistry (ABCD) has helped increase access to dental services by providing dentists higher reimbursements for oral health education and preventive and restorative services for children.[59][60] After the passing of the Affordable Care Act, many dental practices began using dental service organizations to provide business management and support, allowing practices to minimize costs and pass the saving on to patients currently without adequate dental care.[61][62]

Eligibility

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that provides health coverage or nursing home coverage to certain categories of low-asset people, including children, pregnant women, parents of eligible children, people with disabilities and elderly needing nursing home care. Medicaid was created to help low-asset people who fall into one of these eligibility categories "pay for some or all of their medical bills."[63]

While Congress and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) set out the general rules under which Medicaid operates, each state runs its own program. Under certain circumstances, an applicant may be denied coverage. As a result, the eligibility rules differ significantly from state to state, although all states must follow the same basic framework.

As of 2013, Medicaid is a program intended for those with low income, but a low income is not the only requirement to enroll in the program. Eligibility is categorical—that is, to enroll one must be a member of a category defined by statute; some of these categories include low-income children below a certain wage, pregnant women, parents of Medicaid-eligible children who meet certain income requirements, low-income disabled people who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and/or Social Security Disability (SSD), and low-income seniors 65 and older. The details of how each category is defined vary from state to state.

PPACA income test standardization

As of 2019, when Medicaid has been expanded under the PPACA, eligibility is determined by an income test using Modified Adjusted Gross Income, with no state-specific variations and a prohibition on asset or resource tests.[64]

Non-PPACA eligibility

While Medicaid expansion available to adults under the PPACA mandates a standard income-based test without asset or resource tests, other eligibility criteria such as assets may apply when eligible outside of the PPACA expansion,[64] including coverage for eligible seniors or disabled.[65] These other requirements include, but are not limited to, assets, age, pregnancy, disability,[66] blindness, income and resources, and one's status as a U.S. citizen or a lawfully admitted immigrant.[7]

As of 2015, asset tests varied; for example, eight states did not have an asset test for a buy-in available to working people with disabilities, and one state had no asset test for the aged/blind/disabled pathway up to 100% of the FPL.[67]

More recently, many states have authorized financial requirements that will make it more difficult for working-poor adults to access coverage. In Wisconsin, nearly a quarter of Medicaid patients were dropped after the state government imposed premiums of 3% of household income.[68] A survey in Minnesota found that more than half of those covered by Medicaid were unable to obtain prescription medications because of co-payments.[68]

The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 requires anyone seeking Medicaid to produce documents to prove that he is a United States citizen or resident alien. An exception is made for Emergency Medicaid where payments are allowed for the pregnant and disabled regardless of immigration status.[69][70] Special rules exist for those living in a nursing home and disabled children living at home.

Supplemental Security Income beneficiaries

Once someone is approved as a beneficiary in the Supplemental Security Income program, they may automatically be eligible for Medicaid coverage (depending on the laws of the state they reside in).[71]

Five year "look-back"

The DRA created a five-year "look-back period." That means that any transfers without fair market value (gifts of any kind) made by the Medicaid applicant during the preceding five years are penalizable.

The penalty is determined by dividing the average monthly cost of nursing home care in the area or State into the amount of assets gifted. Therefore, if a person gifted $60,000 and the average monthly cost of a nursing home was $6,000, one would divide $6000 into $60,000 and come up with 10. 10 represents the number of months the applicant would not be eligible for medicaid.

All transfers made during the five-year look-back period are totaled, and the applicant is penalized based on that amount after having already dropped below the Medicaid asset limit. This means that after dropping below the asset level ($2,000 limit in most states), the Medicaid applicant will be ineligible for a period of time. The penalty period does not begin until the person is eligible for medicaid but for the gift.[72]

Elders who gift or transfer assets can be caught in the situation of having no money but still not being eligible for Medicaid.

Immigration status

Legal permanent residents (LPRs) with a substantial work history (defined as 40 quarters of Social Security covered earnings) or military connection are eligible for the full range of major federal means-tested benefit programs, including Medicaid (Medi-Cal).[73] LPRs entering after August 22, 1996, are barred from Medicaid for five years, after which their coverage becomes a state option, and states have the option to cover LPRs who are children or who are pregnant during the first five years. Noncitizen SSI recipients are eligible for (and required to be covered under) Medicaid. Refugees and asylees are eligible for Medicaid for seven years after arrival; after this term, they may be eligible at state option.

Nonimmigrants and unauthorized aliens are not eligible for most federal benefits, regardless of whether they are means tested, with notable exceptions for emergency services (e.g., Medicaid for emergency medical care), but states have the option to cover nonimmigrant and unauthorized aliens who are pregnant or who are children, and can meet the definition of "lawfully residing" in the United States. Special rules apply to several limited noncitizen categories: certain "cross-border" American Indians, Hmong/Highland Laotians, parolees and conditional entrants, and cases of abuse.

Aliens outside the United States who seek to obtain visas at US consulates overseas, or admission at US ports of entry, are generally denied entry if they are deemed "likely at any time to become a public charge."[74] Aliens within the United States who seek to adjust their status to that of lawful permanent resident (LPR), or who entered the United States without inspection, are also generally subject to exclusion and deportation on public charge grounds. Similarly, LPRs and other aliens who have been admitted to the United States are removable if they become a public charge within five years after the date of their entry due to causes that preexisted their entry.

A 1999 policy letter from immigration officials defined "public charge" and identified which benefits are considered in public charge determinations, and the policy letter underlies current regulations and other guidance on the public charge grounds of inadmissibility and deportability. Collectively, the various sources addressing the meaning of public charge have historically suggested that an alien's receipt of public benefits, per se, is unlikely to result in the alien being deemed to be removable on public charge grounds.

Children and SCHIP

A child may be eligible for Medicaid regardless of the eligibility status of his parents. Thus, a child may be covered by Medicaid based on his individual status even if his parents are not eligible. Similarly, if a child lives with someone other than a parent, he may still be eligible based on its individual status.[75]

One-third of children and over half (59%) of low-income children are insured through Medicaid or SCHIP. The insurance provides them with access to preventive and primary services which are used at a much higher rate than for the uninsured, but still below the utilization of privately insured patients. As of 2014, rate of uninsured children was reduced to 6% (5 million children remain uninsured).[76]

HIV

Medicaid provided the largest portion of federal money spent on health care for people living with HIV/AIDS until the implementation of Medicare Part D when the prescription drug costs for those eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid shifted to Medicare. Unless low income people who are HIV positive meet some other eligibility category, they are not eligible for Medicaid assistance unless they can qualify under the "disabled" category to receive Medicaid assistance — as, for example, if they progress to AIDS (T-cell count drops below 200).[77] The Medicaid eligibility policy contrasts with the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) guidelines which recommend therapy for all patients with T-cell counts of 350 or less, or in certain patients commencing at an even higher T-cell count. Due to the high costs associated with HIV medications, many patients are not able to begin antiretroviral treatment without Medicaid help. More than half of people living with AIDS in the US are estimated to receive Medicaid payments. Two other programs that provide financial assistance to people living with HIV/AIDS are the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and the Supplemental Security Income.

Utilization

During 2003–2012, the share of hospital stays billed to Medicaid increased by 2.5%, or 0.8 million stays.[78]

Medicaid super utilizers (defined as Medicaid patients with four or more admissions in one year) account for more hospital stays (5.9 vs.1.3 stays), longer length of stay (6.1 vs. 4.5 days), and higher hospital costs per stay ($11,766 vs. $9,032).[79] Medicaid super-utilizers were more likely than other Medicaid patients to be male and to be aged 45–64 years.[79] Common conditions among super-utilizers include mood disorders and psychiatric disorders, as well as diabetes; cancer treatment; sickle cell anemia; sepsis; congestive heart failure; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and complications of devices, implants and grafts.[79]

Budget

Unlike Medicare, which is solely a federal program, Medicaid is a joint federal-state program. Each state operates its own Medicaid system, but this system must conform to federal guidelines in order for the state to receive matching funds and grants. American Samoan, Puerto Rico, Guam, and The US Virgin Islands get a block grant instead.[81] The matching rate provided to states is determined using a federal matching formula (called Federal Medical Assistance Percentages), which generates payment rates that vary from state to state, depending on each state's respective per capita income.[82] The wealthiest states only receive a federal match of 50% while poorer states receive a larger match.[83]

Medicaid funding has become a major budgetary issue for many states over the last few years, with states, on average, spending 16.8% of state general funds on the program. If the federal match expenditure is also counted, the program, on average, takes up 22% of each state's budget.[84][85] Some 43 million Americans were enrolled in 2004 (19.7 million of them children) at a total cost of $295 billion.[86] In 2008, Medicaid provided health coverage and services to approximately 49 million low-income children, pregnant women, elderly people, and disabled people. Federal Medicaid outlays were estimated to be $204 billion in 2008.[87] In 2011, there were 7.6 million hospital stays billed to Medicaid, representing 15.6% (approximately $60.2 billion) of total aggregate inpatient hospital costs in the United States.[88] At $8,000, the mean cost per stay billed to Medicaid was $2,000 less than the average cost for all stays.[89]

Medicaid does not pay benefits to individuals directly; Medicaid sends benefit payments to health care providers. In some states Medicaid beneficiaries are required to pay a small fee (co-payment) for medical services.[7] Medicaid is limited by federal law to the coverage of "medically necessary services".[90]

Since Medicaid program was established in 1965, "states have been permitted to recover from the estates of deceased Medicaid recipients who were over age 65 when they received benefits and who had no surviving spouse, minor child, or adult disabled child."[91] In 1993, Congress enacted the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, which required states to attempt to recoup "the expense of long-term care and related costs for deceased Medicaid recipients 55 or older."[91] The Act also allowed states to recover other Medicaid expenses for deceased Medicaid recipients 55 or older, at each state's choice.[91] However, states are prohibited from estate recovery when "there is a surviving spouse, a child under the age of 21 or a child of any age who is blind or disabled" and "the law also carved out other exceptions for adult children who have served as caretakers in the homes of the deceased, property owned jointly by siblings, and income-producing property, such as farms."[91] Each state now maintains a Medicaid Estate Recovery Program, although the sum of money collected significantly varies from state to state, "depending on how the state structures its program and how vigorously it pursues collections."[91]

Medicaid payments currently assist nearly 60% of all nursing home residents and about 37% of all childbirths in the United States. The federal government pays on average 57% of Medicaid expenses.

On November 25, 2008, a new federal rule was passed that allows states to charge premiums and higher co-payments to Medicaid participants.[92] This rule will enable states to take in greater revenues, limiting financial losses associated with the program. Estimates figure that states will save $1.1 billion while the federal government will save nearly $1.4 billion. However, this means that the burden of financial responsibility will be placed on 13 million Medicaid recipients who will face a $1.3 billion increase in co-payments over 5 years.[93] The major concern is that this rule will create a disincentive for low-income people to seek healthcare. It is possible that this will force only the sickest participants to pay the increased premiums and it is unclear what long-term effect this will have on the program.

A 2019 study found that Medicaid expansion in Michigan had net positive fiscal effects for the state.[94]

Effects

After Medicaid was enacted, some states repealed their filial responsibility laws, but most states still require children to pay for the care of their impoverished parents.

A 2019 review by Kaiser Family Foundation of 324 studies on Medicaid expansion concluded that "expansion is linked to gains in coverage; improvements in access, financial security, and some measures of health status/outcomes; and economic benefits for states and providers."[8]

A 2017 survey of the academic research on Medicaid found it improved recipients' health and financial security.[2] A 2017 paper found that Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act "reduced unpaid medical bills sent to collection by $3.4 billion in its first two years, prevented new delinquencies, and improved credit scores. Using data on credit offers and pricing, we document that improvements in households' financial health led to better terms for available credit valued at $520 million per year. We calculate that the financial benefits of Medicaid double when considering these indirect benefits in addition to the direct reduction in out-of-pocket expenditures."[95] Studies have found that Medicaid expansion reduced the poverty rate,[96] and reduced severe food insecurity.[97]

A 2016 paper found that Medicaid has substantial positive long-term effects on the health of recipients: "Early childhood Medicaid eligibility reduces mortality and disability and, for whites, increases extensive margin labor supply, and reduces receipt of disability transfer programs and public health insurance up to 50 years later. Total income does not change because earnings replace disability benefits."[98] The government recoups its investment in Medicaid through savings on benefit payments later in life and greater payment of taxes because recipients of Medicaid are healthier: "The government earns a discounted annual return of between 2% and 7% on the original cost of childhood coverage for these cohorts, most of which comes from lower cash transfer payments."[98]

A 2018 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that upon its introduction, Medicaid reduced infant and child mortality in the 1960s and 1970s.[99] The decline in the mortality rate for nonwhite children was particularly steep.[99] A 2018 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that the infant mortality rate declined in states that had Medicaid expansions (as part of the Affordable Care Act) whereas the rate rose in states that declined Medicaid expansion.[100]

A 2017 study found that Medicaid enrollment increases political participation (measured in terms of voter registration and turnout).[101]

A 2017 study found that Medicaid expansion, by increasing treatment for substance abuse, "led to a sizeable reduction in the rates of robbery, aggravated assault and larceny theft."[102]

A 2018 study found that Medicaid expansions in New York, Arizona, and Maine in the early 2000s caused a 6% decline in the mortality rate:[103]

HIV-related mortality (affected by the recent introduction of antiretrovirals) accounted for 20% of the effect. Mortality changes were closely linked to county-level coverage gains, with one life saved annually for every 239 to 316 adults gaining insurance. The results imply a cost per life saved ranging from $327,000 to $867,000 which compares favorably with most estimates of the value of a statistical life.

A 2019 paper by Stanford University and Wharton economists found that Medicaid expansion "produced a substantial increase in hospital revenue and profitability, with larger gains for government hospitals. On the benefits side, we do not detect significant improvements in patient health, although the expansion led to substantially greater hospital and emergency room use, and a reallocation of care from public to private and better-quality hospitals."[104]

A 2019 New England Journal of Medicine study found that the implementation of work requirements for Medicaid in Arkansas led to an increase in uninsured individuals without any significant impact on employment.[105][106]

A 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that when Hawaii stopped allowing Compact of Free Association (COFA) migrants to be covered by the state's Medicaid program that Medicaid-funded hospitalizations declined by 69% and emergency room visits declined by 42% for this population, but that uninsured ER visits increased and that Medicaid-funded ER visits by infants substantially increased.[107] Another NBER paper found that Medicaid expansion reduced mortality.[108]

Studies have linked Medicaid expansion with increases in employment levels and student status among enrollees.[109][110][111]

A 2020 JAMA study found that Medicare expansion under the ACA was associated with reduced incidence of advanced-stage breast cancer, indicating that Medicaid accessibility led to early detection of breast cancer and higher survival rates.[112]

Oregon Medicaid health experiment and controversy

In 2008 Oregon decided to hold a randomized lottery for the provision of Medicaid insurance in which 10,000 lower-income people eligible for Medicaid were chosen by a randomized system. The lottery enabled studies to accurately measure the impact of health insurance on an individual's health and eliminate potential selection bias in the population enrolling in Medicaid.

A sequence of two high-profile studies by a team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Harvard School of Public Health [113] found that "Medicaid coverage generated no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years", but did "increase use of health care services, raise rates of diabetes detection and management, lower rates of depression, and reduce financial strain."

The study found that in the first year:[114]

- Hospital use increased by 30% for those with insurance, with the length of hospital stays increasing by 30% and the number of procedures increasing by 45% for the population with insurance;

- Medicaid recipients proved more likely to seek preventive care. Women were 60% more likely to have mammograms, and recipients overall were 20% more likely to have their cholesterol checked;

- In terms of self-reported health outcomes, having insurance was associated with an increased probability of reporting one's health as "good," "very good," or "excellent"—overall, about 25% higher than the average;

- Those with insurance were about 10% less likely to report a diagnosis of depression.

- Patients with catastrophic health spending (with costs that were greater than 30% of income) dropped.

- Medicaid patients had cut in half the probability of requiring loans or forgoing other bills to pay for medical costs.[115]

The studies spurred a debate between proponents of expanding Medicaid coverage,[116] and fiscal conservatives challenging the value of this expansive government program.[117]

Privatization and automation of Medicaid in Indiana

Main source: Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor, Ch. 2 [118]

In 2006, Gov. Mitch Daniels signed a contract outsourcing and automating Indiana's welfare program in an effort to reduce fraud, cut spending, and help recipients move off of welfare programs. It was a $1.3 billion contract meant to last ten years, but within 3 years, IBM and Indiana sued each other for breaching the contract. The state claimed that IBM had not improved the welfare system after many complaints from welfare recipients. The court ruled that IBM was responsible for $78 million in damages to the state. IBM claims to have invested significant resources to bettering the welfare system of Indiana.[119] Privatization and automation can have catastrophic consequences when not implemented properly. In this case, due to long automated calls, untrained workers, mismanagement of documents, poor data collection, and a variety of other issues, this contract cost millions in damages and created a great amount of stress for those who relied on welfare programs such as medicaid to survive. The state sought to eliminate personal relationships by automating the system and making sure that no singular person would oversee a specific case. The new automated application system was extremely rigid and any deviation would result in denial of benefits. Many poor and working-class people lost their benefits and had to enter a grueling process to prove their eligibility.[118] This solution was technologically deterministic in that it sought to solve major societal issues simply by automating processes that were deemed ineffective. Eliminating human connection and face to face interaction completely, especially when dealing with a government program, can create far more problems than it solves. The resulting legal battle between the state and a private corporation demonstrates the issue of a submerged state and begs the question of who becomes responsible for government welfare and Medicaid after privatization?

A study printed in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law introduces the issue of a "submerged" state when welfare programs are privatized. The study analyzed medicaid self-reported enrollment numbers under a privatized system that "obscured" the role of the government. It concluded that privatized welfare systems that create new administrative structures decrease the self-reported medicaid enrollment numbers.[120] Many people who rely on welfare programs and are legally eligible for aid could potentially miss out on benefits due to the outsourcing of management. It could be argued that it is crucial that the state remain the primary authority and administrators of welfare programs. Otherwise, as described in chapter two of Automating Inequality, families could be caught in the crossfire and potentially be put in life-threatening situations. There could be systems of privatization that work efficiently, but they require study and careful implementation, otherwise there could be life changing consequences for individuals and families.

See also

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation

- Enhanced Primary Care Case Management Program

- Medicaid estate recovery

- Home and Community-Based Services Waivers

- State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP/CHIP)

- United States National Health Care Act

References

- America's Health Insurance Plans (HIAA), p. 232

- Gottlieb JD, Shepard M (July 2, 2017). "Evidence on the Value of Medicaid". Econofact. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- Terhune, Chad (October 18, 2018). "Private Medicaid Plans Receive Billions In Tax Dollars, With Little Oversight". Health Shots. NPR. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

...Medicaid, the nation's public insurance program that assists 75 million low-income Americans.

- Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017 (Report). United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 1, 2017. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

Estimated United States population as of July 1, 2017 = 325,719,178

- "Medicaid General Info". www.cms.hhs.gov.

- "Coverage for lawfully present immigrants". Healthcare.gov. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- "Eligibility". www.medicaid.gov. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Antonisse, Larisa; Aug 15, Madeline Guth Published; 2019 (August 15, 2019). "The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved September 26, 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "About Medicare". www.medicare.gov. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in Baltimore. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- "States Turn to Managed Care To Constrain Medicaid Long-Term Care Costs". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 9, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- "Managed Care". medicaid.gov. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- "Medicaid pyments per enrollee". KFF.org. June 9, 2017.

- "Annual Statistical Supplement". U.S. Social Security Administration, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- "Medicaid Drug Rebate Program Overview". HHS. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007.

- "Medicaid Estate Recovery". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 2005.

- "Fee for Service (Direct Service) Program". Medicaid.gov. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- HHS Press Office (March 29, 2013). "HHS finalizes rule guaranteeing 100 percent funding for new Medicaid beneficiaries". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

effective January 1, 2014, the federal government will pay 100 percent of defined cost of certain newly eligible adult Medicaid beneficiaries. These payments will be in effect through 2016, phasing down to a permanent 90 percent matching rate by 2020.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (April 2, 2013). "Medicaid program: Increased federal medical assistance percentage changes under the Affordable Care Act of 2010: Final rule". Federal Register. 78 (63): 19917–47. PMID 23556184.(A) 100 percent, for calendar quarters in calendar years (CYs) 2014 through 2016; (B) 95 percent, for calendar quarters in CY 2017; (C) 94 percent, for calendar quarters in CY 2018; (D) 93 percent, for calendar quarters in CY 2019;(E) 90 percent, for calendar quarters in CY 2020 and all subsequent calendar years.

- Pear R (May 24, 2013). "States' Policies on Health Care Exclude Some of the Poorest". The New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

In most cases, [Sandy Praeger, Insurance Commissioner of Kansas] said, adults with incomes from 32 percent to 100 percent of the poverty level ($6,250 to $19,530 for a family of three) "will have no assistance."

- Kliff S (May 5, 2013). "Florida rejects Medicaid expansion, leaves 1 million uninsured". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- "To Date, 20 States & DC Plan to Expand Medicaid Eligibility, 14 Will Not Expand, and the Remainder Are Undecided" (PDF). AvalereHealth.Net. May 2, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

© Avalere Health LLC To Date, 20 States & DC Plan to Expand Medicaid Eligibility, 14 Will Not Expand, and the Remainder Are Undecided

- "Where each state stands on ACA's Medicaid expansion: A roundup of what each state's leadership has said about their Medicaid plans". The Advisory Board Company. May 24, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Barrilleaux, Charles; Rainey, Carlisle (December 11, 2014). "The Politics of Need". State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 14 (4): 437–460. doi:10.1177/1532440014561644.

- Jacobs, Lawrence R.; Callaghan, Timothy (October 2013). "Why States Expand Medicaid: Party, Resources, and History". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 38 (5): 1023–1050. doi:10.1215/03616878-2334889. PMID 23794741.

- Lanford, Daniel; Quadagno, Jill (July 14, 2015). "Implementing ObamaCare". Sociological Perspectives. 59 (3): 619–639. doi:10.1177/0731121415587605.

- "Archive-It - News Releases". www.hhs.gov. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Angeles, January (July 11, 2012). "How Health Reform's Medicaid Expansion Will Impact State Budgets". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- "Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- "Next Steps on Medicaid Expansion Announced" (Press release). Anchorage, AK: State of Alaska. July 16, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- "Where the states stand on Medicaid expansion". www.advisory.com. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- Roubein, Rachel. "Oklahoma voters approve Medicaid expansion as coronavirus cases climb". POLITICO. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Live Results: Missouri Medicaid Expansion Amendment". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- Goldstein A, Snell K (June 26, 2017). "Senate GOP health-care bill appears in deeper trouble following new CBO report". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- Dáil, Paula vW. (2012). Women and Poverty in 21st Century America. NC, USA: McFarland. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7864-4903-3. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013.

- "Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Offer Free Or Low-Cost Health Coverage To Children And Families" (PDF). United States Department of Labor/Employee Benefits Security Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Lukens, G. (September 23, 2014). "State Variation in Health Care Spending and the Politics of State Medicaid Policy". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 39 (6): 1213–1251. doi:10.1215/03616878-2822634. PMID 25248962.

- Rose, Shanna (January 1, 2015). "Opting In, Opting Out: The Politics of State Medicaid Expansion". The Forum. 13 (1). doi:10.1515/for-2015-0011.

- Zaloshnja, Eduard; Miller, Ted R.; Coben, Jeffrey; Steiner, Claudia (June 2012). "How Often Do Catastrophic Injury Victims Become Medicaid Recipients?". Medical Care. 50 (6): 513–519. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a686. JSTOR 23216705. PMID 22270099.

- Mojtabai, Ramin; Feder, Kenneth A.; Kealhofer, Marc; Krawczyk, Noa; Storr, Carla; Tormohlen, Kayla N.; Young, Andrea S.; Olfson, Mark; Crum, Rosa M. (June 2018). "State variations in Medicaid enrollment and utilization of substance use services: Results from a National Longitudinal Study". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 89: 75–86. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.04.002. PMC 5964257. PMID 29706176.

- Lalezari, Ramin M.; Pozen, Alexis; Dy, Christopher J. (February 2018). "State Variation in Medicaid Reimbursements for Orthopaedic Surgery". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 100 (3): 236–242. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00279. PMID 29406345.

- "Overview". www.cms.hhs.gov. November 15, 2016.

- CMS. "A Profile of Medicaid: Chartbook 2000" (PDF). Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- Witt WP, Wiess AJ, Elixhauser A (December 2014). "Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #186. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Office of the Actuary (December 21, 2010). "2010 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid" (PDF). www.cms.gov.

- Medi-Cal Program Enrollment Totals for Fiscal Year 2009–10 Archived June 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, California Department of Health Care Services Research and Analytic Studies Section, June 2011

- Sack K (September 30, 2010). "Recession Drove Millions to Medicaid in '09, Survey Finds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Medicaid Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Medicare.gov – Long-Term Care Archived April 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Dual Eligible". www.cms.gov. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008.

- "Medi-Medi Dual Eligibility - Medicare, Medicaid and You - SeniorQuote". seniorquote.com.

- "State–Federal Program Provides Capitated Payments to Plans Serving Those Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, Leading to Better Access to Care and Less Hospital and Nursing Home Use". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Alker J (2008). "Choosing Premium AssistanceH: What does State experience tell us?" (PDF). The Kaiser Family Foundation.

- "Dental Coverage Overview". Medicaid. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- "Dental Guide" (PDF). HHS. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2011.

- "CDHP.org" (PDF). cdhp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Factors Contributing to Low Use of Dental Services by Low-Income Populations. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office. 2000.

- Gehshan S, Hauck P, and Scales J. Increasing dentists' participation in Medicaid and SCHIP. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures. 2001. Ecom.ncsl.org

- Edelstein B. Barriers to Medicaid Dental Care. Washington, DC: Children's Dental Health Project. 2000. CDHP.org

- Krol D and Wolf JC. Physicians and dentists attitudes toward Medicaid and Medicaid patients: review of the literature. Columbia University. 2009.

- "Comprehensive Statewide Program Combines Training and Higher Reimbursement for Providers With Outreach and Education for Families, Enhancing Access to Dental Care for Low-Income Children". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 27, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- "Medicaid Reimbursement and Training Enable Primary Care Providers to Deliver Preventive Dental Care at Well-Child Visits, Enhancing Access for Low-Income Children". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. July 17, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- "About DSOs". Association of Dental Support Organizations. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- Winegarden, Wayne. "Benefits Created by Dental Service Organizations" (PDF). Pacific Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016.

- "Medicaid Eligibility: Overview," Archived January 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) website

- "Eligibility". www.medicaid.gov. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- "1115 Waiver Element: Asset Tests". Families USA. November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- "Medicare/Medicaid". ID-DD Resources. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Watts, Molly O'Malley; Cornachione, Elizabeth; 2016 (March 1, 2016). "Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities in 2015 - Report". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Making Medicaid Work" (PDF). www.policymattersohio.org.

- "Pregnant Illegal Aliens Overwhelming Emergency Medicaid". Newsmax.com. March 14, 2007. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- "Healthcare for Wisconsin Residents" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ORDP.OPDR. "Medicaid Information". www.ssa.gov. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- 42 U.S.C. 1396p

- RL33809 Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview (Report). Congressional Research Service. December 12, 2016.

- R43220 Public Charge Grounds of Inadmissibility and Deportability: Legal Overview (Report). Congressional Research Service. February 6, 2017.

- "CMS.hhs.gov" (PDF). hhs.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Cornachione, Elizabeth; Rudowitz, Robin; Artiga, Samantha (June 27, 2016). "Children's Health Coverage: The Role of Medicaid and CHIP and Issues for the Future". Kaiser Family Foundation.

- "Medicaid and HIV/AIDS," Kaiser Family Foundation, fact sheet, kff.org

- Wiess AJ, Elixhauser A (October 2014). "Overview of Hospital Utilization, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Jiang HJ, Barrett ML, Sheng M (November 2014). "Characteristics of Hospital Stays for Nonelderly Medicaid Super-Utilizers, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #184. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- The Long-Term Outlook for Health Care Spending. Figure 2. Congressional Budget Office.

- "Puerto Rico's Post-Maria Medicaid Crisis". June 11, 2019.

- SSA.gov, Social Security Act. Title IX, Sec. 1101(a)(8)(B)

- Mitchell, Alison (April 25, 2018). Medicaid's Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- "Microsoft Word – Final Text.doc" (PDF). nasbo.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- "Medicaid and State Budgets: Looking at the Facts", Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, May 2008.

- "Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid". January 6, 2009.

- "Budget of the United States Government, FY 2008", Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- Torio CM, Andrews RM. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. August 2013.

- Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C (December 2013). "Costs for Hospital Stays in the United States, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #168. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Adler PW (December 2011). "Is it lawful to use Medicaid to pay for circumcision?" (PDF). Journal of Law and Medicine. 19 (2): 335–53. PMID 22320007. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- Eugene Kiely, Medicaid Estate Recovery Program, FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania (January 10, 2014).

- search: 42 CFR Parts 447 and 457 Archived March 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Pear, Robert (November 27, 2008). "New Medicaid Rules Allow States to Set Premiums and Higher Co-Payments". The New York Times.

- Levy, Helen; Ayanian, John Z.; Buchmueller, Thomas C.; Grimes, Donald R.; Ehrlich, Gabriel (2020). "Macroeconomic Feedback Effects of Medicaid Expansion: Evidence from Michigan". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 45: 5–48. doi:10.1215/03616878-7893555. PMID 31675091.

- Brevoort, Kenneth; Grodzicki, Daniel; Hackmann, Martin B (November 2017). "Medicaid and Financial Health". NBER Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research: 24002. doi:10.3386/w24002.

- Zewde, Naomi; Wimer, Christopher (January 2019). "Antipoverty Impact Of Medicaid Growing With State Expansions Over Time". Health Affairs. 38 (1): 132–138. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05155. PMID 30615519.

- Himmelstein, Gracie (July 18, 2019). "Effect of the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid Expansions on Food Security, 2010–2016". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (9): e1–e6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305168. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6687269. PMID 31318597.

- Goodman-Bacon, Andrew (December 2016). "The Long-Run Effects of Childhood Insurance Coverage: Medicaid Implementation, Adult Health, and Labor Market Outcomes". NBER Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research: 22899. doi:10.3386/w22899.

- Goodman-Bacon, Andrew (February 2018). "Public Insurance and Mortality: Evidence from Medicaid Implementation" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 126 (1): 216–262. doi:10.1086/695528.

- Bhatt, Chintan B.; Beck-Sagué, Consuelo M. (April 2018). "Medicaid Expansion and Infant Mortality in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (4): 565–7. doi:10.2105/ajph.2017.304218. PMC 5844390. PMID 29346003.

- Clinton, Joshua D.; Sances, Michael W. (November 2, 2017). "The Politics of Policy: The Initial Mass Political Effects of Medicaid Expansion in the States". American Political Science Review. 112 (1): 167–185. doi:10.1017/S0003055417000430.

- Wen, Hefei; Hockenberry, Jason M.; Cummings, Janet R. (October 2017). "The effect of Medicaid expansion on crime reduction: Evidence from HIFA-waiver expansions". Journal of Public Economics. 154: 67–94. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.09.001.

- Sommers, Benjamin D. (July 2017). "State Medicaid Expansions and Mortality, Revisited: A Cost-Benefit Analysis" (PDF). American Journal of Health Economics. 3 (3): 392–421. doi:10.1162/ajhe_a_00080.

- Duggan, Mark; Gupta, Atul; Jackson, Emilie (2019). "The Impact of the Affordable Care Act: Evidence from California's Hospital Sector". NBER Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research: 25488. doi:10.3386/w25488.

- Galewitz, Phil (June 19, 2019). "Arkansas' Medicaid work requirement left people uninsured without boosting employment". latimes.com. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- Sommers, Benjamin D.; Goldman, Anna L.; Blendon, Robert J.; Orav, E. John; Epstein, Arnold M. (June 19, 2019). "Medicaid Work Requirements — Results from the First Year in Arkansas". New England Journal of Medicine. 0 (11): 1073–1082. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1901772. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31216419.

- Halliday, Timothy J; Akee, Randall Q; Sentell, Tetine; Inada, Megan; Miyamura, Jill (2019). "The Impact of Medicaid on Medical Utilization in a Vulnerable Population: Evidence from COFA Migrants". doi:10.3386/w26030. hdl:10419/215175. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Miller, Sarah; Altekruse, Sean; Johnson, Norman; Wherry, Laura R (2019). "Medicaid and Mortality: New Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data". doi:10.3386/w26081. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tipirneni, Renuka; Ayanian, John Z.; Patel, Minal R.; Kieffer, Edith C.; Kirch, Matthias A.; Bryant, Corey; Kullgren, Jeffrey T.; Clark, Sarah J.; Lee, Sunghee; Solway, Erica; Chang, Tammy (January 3, 2020). "Association of Medicaid Expansion With Enrollee Employment and Student Status in Michigan". JAMA Network Open. 3 (1): e1920316. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20316. PMID 32003820.

- Hall, Jean P.; Shartzer, Adele; Kurth, Noelle K.; Thomas, Kathleen C. (July 19, 2018). "Medicaid Expansion as an Employment Incentive Program for People With Disabilities". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (9): 1235–1237. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304536. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 6085052. PMID 30024794.

- Hall, Jean P.; Shartzer, Adele; Kurth, Noelle K.; Thomas, Kathleen C. (December 20, 2016). "Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Workforce Participation for People With Disabilities". American Journal of Public Health. 107 (2): 262–264. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303543. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5227925. PMID 27997244.

- Blanc, Justin M. Le; Heller, Danielle R.; Friedrich, Ann; Lannin, Donald R.; Park, Tristen S. (July 1, 2020). "Association of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act With Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis". JAMA Surgery. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1495.

- Baicker, Katherine; Taubman, Sarah L.; Allen, Heidi L.; Bernstein, Mira; Gruber, Jonathan H.; Newhouse, Joseph P.; Schneider, Eric C.; Wright, Bill J.; Zaslavsky, Alan M. (May 2, 2013). "The Oregon Experiment — Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes". New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (18): 1713–1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 3701298. PMID 23635051.

- Olver, Christopher (July 11, 2011). "Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year". journalistsresource.org.

- "More study needed". The Economist. May 6, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- Fung, Brian (June 26, 2012). "What Actually Happens When You Expand Medicaid, as Obamacare Does?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- Roy, Avik. "Oregon Study: Medicaid 'Had No Significant Effect' On Health Outcomes vs. Being Uninsured". Forbes. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- Eubanks, Virginia, Automating Inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor, Tantor Media, ISBN 9781977384423, OCLC 1043038943

- "Judge: IBM owes Indiana $78M for failed welfare automation". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Tallevi, Ashley (April 1, 2018). "Out of Sight, Out of Mind? Measuring the Relationship between Privatization and Medicaid Self-Reporting". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 43 (2): 137–183. doi:10.1215/03616878-4303489. ISSN 0361-6878. PMID 29630705.

Further reading

- House Ways and Means Committee, 2004 Green Book – Overview of the Medicaid Program, United States House of Representatives, 2004.

External links

- CMS official web site

- Health Assistance Partnership

- Trends in Medicaid, October 2006. Staff Paper of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Medicaid

- "Medicaid Research" and "Medicaid Primer" from Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

- Kaiser Family Foundation – Substantial resources on Medicaid including federal eligibility requirements, benefits, financing and administration.

- "The Role of Medicaid in State Economies: A Look at the Research," Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2013

- State-level data on health care spending, utilization, and insurance coverage, including details extensive Medicaid information.

- History of Medicaid in an interactive timeline of key developments.

- Coverage By State – Information on state health coverage, including Medicaid, by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation & AcademyHealth.

- Medicaid information from Families USA

- Medicaid Reform – The Basics from The Century Foundation

- National Association of State Medicaid Directors Organization representing the chief executives of state Medicaid programs.

- Ranking of state Medicaid programs by eligibility, scope of services, quality of service and reimbursement from Public Citizen. 2007.

- Center for Health Care Strategies, CHCS Extensive library of tools, briefs, and reports developed to help state agencies, health plans and policymakers improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of Medicaid.