Eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three celestial objects is known as a syzygy.[1] Apart from syzygy, the term eclipse is also used when a spacecraft reaches a position where it can observe two celestial bodies so aligned. An eclipse is the result of either an occultation (completely hidden) or a transit (partially hidden).

The term eclipse is most often used to describe either a solar eclipse, when the Moon's shadow crosses the Earth's surface, or a lunar eclipse, when the Moon moves into the Earth's shadow. However, it can also refer to such events beyond the Earth–Moon system: for example, a planet moving into the shadow cast by one of its moons, a moon passing into the shadow cast by its host planet, or a moon passing into the shadow of another moon. A binary star system can also produce eclipses if the plane of the orbit of its constituent stars intersects the observer's position.

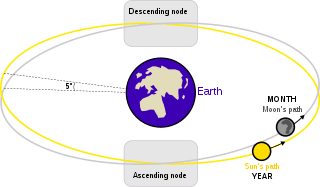

For the special cases of solar and lunar eclipses, these only happen during an "eclipse season", the two times of each year when the plane of the Earth's orbit around the Sun crosses with the plane of the Moon's orbit around the Earth. The type of solar eclipse that happens during each season (whether total, annular, hybrid, or partial) depends on apparent sizes of the Sun and Moon. If the orbit of the Earth around the Sun, and the Moon's orbit around the Earth were both in the same plane with each other, then eclipses would happen each and every month. There would be a lunar eclipse at every full moon, and a solar eclipse at every new moon. And if both orbits were perfectly circular, then each solar eclipse would be the same type every month. It is because of the non-planar and non-circular differences that eclipses are not a common event. Lunar eclipses can be viewed from the entire nightside half of the Earth. But solar eclipses, particularly total eclipses occurring at any one particular point on the Earth's surface, are very rare events that can be many decades apart.

Etymology

The term is derived from the ancient Greek noun ἔκλειψις (ékleipsis), which means "the abandonment", "the downfall", or "the darkening of a heavenly body", which is derived from the verb ἐκλείπω (ekleípō) which means "to abandon", "to darken", or "to cease to exist,"[2] a combination of prefix ἐκ- (ek-), from preposition ἐκ (ek), "out," and of verb λείπω (leípō), "to be absent".[3][4]

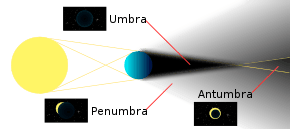

Umbra, penumbra and antumbra

For any two objects in space, a line can be extended from the first through the second. The latter object will block some amount of light being emitted by the former, creating a region of shadow around the axis of the line. Typically these objects are moving with respect to each other and their surroundings, so the resulting shadow will sweep through a region of space, only passing through any particular location in the region for a fixed interval of time. As viewed from such a location, this shadowing event is known as an eclipse.[5]

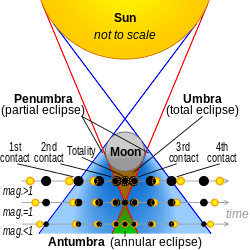

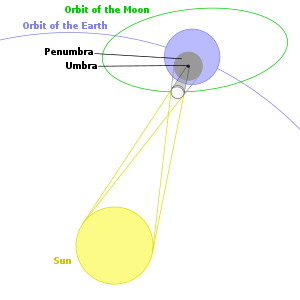

Typically the cross-section of the objects involved in an astronomical eclipse are roughly disk shaped.[5] The region of an object's shadow during an eclipse is divided into three parts:[6]

- The umbra, within which the object completely covers the light source. For the Sun, this light source is the photosphere.

- The antumbra, extending beyond the tip of the umbra, within which the object is completely in front of the light source but too small to completely cover it.

- The penumbra, within which the object is only partially in front of the light source.

A total eclipse occurs when the observer is within the umbra, an annular eclipse when the observer is within the antumbra, and a partial eclipse when the observer is within the penumbra. During a lunar eclipse only the umbra and penumbra are applicable, because the antumbra of the Sun-Earth system lies far beyond the Moon. Analagously, Earth's apparent diameter from the viewpoint of the Moon is nearly four times that of the Sun and thus cannot produce an annular eclipse. The same terms may be used analogously in describing other eclipses, e.g., the antumbra of Deimos crossing Mars, or Phobos entering Mars's penumbra.

The first contact occurs when the eclipsing object's disc first starts to impinge on the light source; second contact is when the disc moves completely within the light source; third contact when it starts to move out of the light; and fourth or last contact when it finally leaves the light source's disc entirely.

For spherical bodies, when the occulting object is smaller than the star, the length (L) of the umbra's cone-shaped shadow is given by:

where Rs is the radius of the star, Ro is the occulting object's radius, and r is the distance from the star to the occulting object. For Earth, on average L is equal to 1.384×106 km, which is much larger than the Moon's semimajor axis of 3.844×105 km. Hence the umbral cone of the Earth can completely envelop the Moon during a lunar eclipse.[7] If the occulting object has an atmosphere, however, some of the luminosity of the star can be refracted into the volume of the umbra. This occurs, for example, during an eclipse of the Moon by the Earth—producing a faint, ruddy illumination of the Moon even at totality.

On Earth, the shadow cast during an eclipse moves very approximately at 1 km per sec. This depends on the location of the shadow on the Earth and the angle in which it is moving.[8]

Eclipse cycles

An eclipse cycle takes place when eclipses in a series are separated by a certain interval of time. This happens when the orbital motions of the bodies form repeating harmonic patterns. A particular instance is the saros, which results in a repetition of a solar or lunar eclipse every 6,585.3 days, or a little over 18 years. Because this is not a whole number of days, successive eclipses will be visible from different parts of the world.[9]

Earth–Moon system

An eclipse involving the Sun, Earth, and Moon can occur only when they are nearly in a straight line, allowing one to be hidden behind another, viewed from the third. Because the orbital plane of the Moon is tilted with respect to the orbital plane of the Earth (the ecliptic), eclipses can occur only when the Moon is close to the intersection of these two planes (the nodes). The Sun, Earth and nodes are aligned twice a year (during an eclipse season), and eclipses can occur during a period of about two months around these times. There can be from four to seven eclipses in a calendar year, which repeat according to various eclipse cycles, such as a saros.

Between 1901 and 2100 there are the maximum of seven eclipses in:[10]

- four (penumbral) lunar and three solar eclipses: 1908, 2038.

- four solar and three lunar eclipses: 1918, 1973, 2094.

- five solar and two lunar eclipses: 1934.

Excluding penumbral lunar eclipses, there are a maximum of seven eclipses in:[11]

- 1591, 1656, 1787, 1805, 1918, 1935, 1982, and 2094.

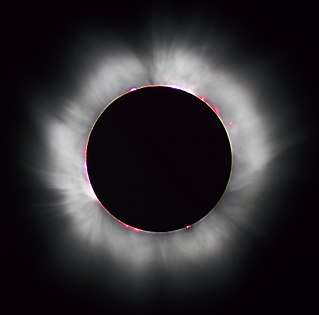

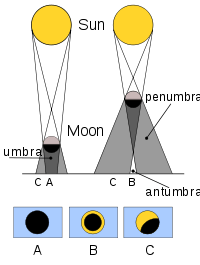

Solar eclipse

As observed from the Earth, a solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes in front of the Sun. The type of solar eclipse event depends on the distance of the Moon from the Earth during the event. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Earth intersects the umbra portion of the Moon's shadow. When the umbra does not reach the surface of the Earth, the Sun is only partially occulted, resulting in an annular eclipse. Partial solar eclipses occur when the viewer is inside the penumbra.[12]

The eclipse magnitude is the fraction of the Sun's diameter that is covered by the Moon. For a total eclipse, this value is always greater than or equal to one. In both annular and total eclipses, the eclipse magnitude is the ratio of the angular sizes of the Moon to the Sun.[13]

Solar eclipses are relatively brief events that can only be viewed in totality along a relatively narrow track. Under the most favorable circumstances, a total solar eclipse can last for 7 minutes, 31 seconds, and can be viewed along a track that is up to 250 km wide. However, the region where a partial eclipse can be observed is much larger. The Moon's umbra will advance eastward at a rate of 1,700 km/h, until it no longer intersects the Earth's surface.

During a solar eclipse, the Moon can sometimes perfectly cover the Sun because its apparent size is nearly the same as the Sun's when viewed from the Earth. A total solar eclipse is in fact an occultation while an annular solar eclipse is a transit.

When observed at points in space other than from the Earth's surface, the Sun can be eclipsed by bodies other than the Moon. Two examples include when the crew of Apollo 12 observed the Earth to eclipse the Sun in 1969 and when the Cassini probe observed Saturn to eclipse the Sun in 2006.

Lunar eclipse

Lunar eclipses occur when the Moon passes through the Earth's shadow. This happens only during a full moon, when the Moon is on the far side of the Earth from the Sun. Unlike a solar eclipse, an eclipse of the Moon can be observed from nearly an entire hemisphere. For this reason it is much more common to observe a lunar eclipse from a given location. A lunar eclipse lasts longer, taking several hours to complete, with totality itself usually averaging anywhere from about 30 minutes to over an hour.[14]

There are three types of lunar eclipses: penumbral, when the Moon crosses only the Earth's penumbra; partial, when the Moon crosses partially into the Earth's umbra; and total, when the Moon crosses entirely into the Earth's umbra. Total lunar eclipses pass through all three phases. Even during a total lunar eclipse, however, the Moon is not completely dark. Sunlight refracted through the Earth's atmosphere enters the umbra and provides a faint illumination. Much as in a sunset, the atmosphere tends to more strongly scatter light with shorter wavelengths, so the illumination of the Moon by refracted light has a red hue,[15] thus the phrase 'Blood Moon' is often found in descriptions of such lunar events as far back as eclipses are recorded.[16]

Historical record

Records of solar eclipses have been kept since ancient times. Eclipse dates can be used for chronological dating of historical records. A Syrian clay tablet, in the Ugaritic language, records a solar eclipse which occurred on March 5, 1223 B.C.,[17] while Paul Griffin argues that a stone in Ireland records an eclipse on November 30, 3340 B.C.[18] Positing classical-era astronomers' use of Babylonian eclipse records mostly from the 13th century BC provides a feasible and mathematically consistent[19] explanation for the Greek finding all three lunar mean motions (synodic, anomalistic, draconitic) to a precision of about one part in a million or better. Chinese historical records of solar eclipses date back over 3,000 years and have been used to measure changes in the Earth's rate of spin.[20]

By the 1600s, European astronomers were publishing books with diagrams explaining how lunar and solar eclipses occurred.[21][22] In order to disseminate this information to a broader audience and decrease fear of the consequences of eclipses, booksellers printed broadsides explaining the event either using the science or via astrology.[23]

Other planets and dwarf planets

Gas giants

The gas giant planets have many moons and thus frequently display eclipses. The most striking involve Jupiter, which has four large moons and a low axial tilt, making eclipses more frequent as these bodies pass through the shadow of the larger planet. Transits occur with equal frequency. It is common to see the larger moons casting circular shadows upon Jupiter's cloudtops.

The eclipses of the Galilean moons by Jupiter became accurately predictable once their orbital elements were known. During the 1670s, it was discovered that these events were occurring about 17 minutes later than expected when Jupiter was on the far side of the Sun. Ole Rømer deduced that the delay was caused by the time needed for light to travel from Jupiter to the Earth. This was used to produce the first estimate of the speed of light.[24]

On the other three gas giants (Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) eclipses only occur at certain periods during the planet's orbit, due to their higher inclination between the orbits of the moon and the orbital plane of the planet. The moon Titan, for example, has an orbital plane tilted about 1.6° to Saturn's equatorial plane. But Saturn has an axial tilt of nearly 27°. The orbital plane of Titan only crosses the line of sight to the Sun at two points along Saturn's orbit. As the orbital period of Saturn is 29.7 years, an eclipse is only possible about every 15 years.

The timing of the Jovian satellite eclipses was also used to calculate an observer's longitude upon the Earth. By knowing the expected time when an eclipse would be observed at a standard longitude (such as Greenwich), the time difference could be computed by accurately observing the local time of the eclipse. The time difference gives the longitude of the observer because every hour of difference corresponded to 15° around the Earth's equator. This technique was used, for example, by Giovanni D. Cassini in 1679 to re-map France.[25]

Mars

On Mars, only partial solar eclipses (transits) are possible, because neither of its moons is large enough, at their respective orbital radii, to cover the Sun's disc as seen from the surface of the planet. Eclipses of the moons by Mars are not only possible, but commonplace, with hundreds occurring each Earth year. There are also rare occasions when Deimos is eclipsed by Phobos.[26] Martian eclipses have been photographed from both the surface of Mars and from orbit.

Pluto

Pluto, with its proportionately largest moon Charon, is also the site of many eclipses. A series of such mutual eclipses occurred between 1985 and 1990.[27] These daily events led to the first accurate measurements of the physical parameters of both objects.[28]

Mercury and Venus

Eclipses are impossible on Mercury and Venus, which have no moons. However, both have been observed to transit across the face of the Sun. There are on average 13 transits of Mercury each century. Transits of Venus occur in pairs separated by an interval of eight years, but each pair of events happen less than once a century.[29] According to NASA, the next pair of transits will occur on December 10, 2117 and December 8, 2125. Transits on Mercury are much more common.[30]

Eclipsing binaries

A binary star system consists of two stars that orbit around their common centre of mass. The movements of both stars lie on a common orbital plane in space. When this plane is very closely aligned with the location of an observer, the stars can be seen to pass in front of each other. The result is a type of extrinsic variable star system called an eclipsing binary.

The maximum luminosity of an eclipsing binary system is equal to the sum of the luminosity contributions from the individual stars. When one star passes in front of the other, the luminosity of the system is seen to decrease. The luminosity returns to normal once the two stars are no longer in alignment.[31]

The first eclipsing binary star system to be discovered was Algol, a star system in the constellation Perseus. Normally this star system has a visual magnitude of 2.1. However, every 2.867 days the magnitude decreases to 3.4 for more than nine hours. This is caused by the passage of the dimmer member of the pair in front of the brighter star.[32] The concept that an eclipsing body caused these luminosity variations was introduced by John Goodricke in 1783.[33]

Types

Sun - Moon - Earth: Solar eclipse | annular eclipse | hybrid eclipse | partial eclipse

Sun - Earth - Moon: Lunar eclipse | penumbral eclipse | partial lunar eclipse | central lunar eclipse

Sun - Phobos - Mars: Transit of Phobos from Mars | Solar eclipses on Mars

Sun - Deimos - Mars: Transit of Deimos from Mars | Solar eclipses on Mars

Other types: Solar eclipses on Jupiter | Solar eclipses on Saturn | Solar eclipses on Uranus | Solar eclipses on Neptune | Solar eclipses on Pluto

References

- Staff (March 31, 1981). "Science Watch: A Really Big Syzygy". The New York Times (Press release). Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- "in.gr". Archived from the original on 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- "LingvoSoft". lingvozone.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- Westfall, John; Sheehan, William (2014), Celestial Shadows: Eclipses, Transits, and Occultations, Astrophysics and Space Science Library, 410, Springer, pp. 1–5, ISBN 978-1493915354.

- Espenak, Fred (September 21, 2007). "Glossary of Solar Eclipse Terms". NASA. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- Green, Robin M. (1985). Spherical Astronomy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31779-5.

- "Speed of eclipse shadow? - Sciforums". sciforums.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Espenak, Fred (July 12, 2007). "Eclipses and the Saros". NASA. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- Smith, Ian Cameron. "Eclipse Statistics". moonblink.info. Archived from the original on 2014-05-27.

- Gent, R.H. van. "A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles". staff.science.uu.nl. Archived from the original on 2011-09-05.

- Hipschman, R. (2015-10-29). "Solar Eclipse: Why Eclipses Happen". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- Zombeck, Martin V. (2006). Handbook of Space Astronomy and Astrophysics (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-521-78242-5.

- Staff (January 6, 2006). "Solar and Lunar Eclipses". NOAA. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Phillips, Tony (February 13, 2008). "Total Lunar Eclipse". NASA. Archived from the original on March 1, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- Ancient Timekeepers, "Archived copy". 2011-09-16. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-10-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- de Jong, T.; van Soldt, W. H. (1989). "The earliest known solar eclipse record redated". Nature. 338 (6212): 238–240. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..238D. doi:10.1038/338238a0.

- Griffin, Paul (2002). "Confirmation of World's Oldest Solar Eclipse Recorded in Stone". The Digital Universe. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- See DIO 16 Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine p.2 (2009). Though those Greek and perhaps Babylonian astronomers who determined the three previously unsolved lunar motions were spread over more than four centuries (263 BC to 160 AD), the math-indicated early eclipse records are all from a much smaller span Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine: the 13th century BC. The anciently attested Greek technique: use of eclipse cycles, automatically providing integral ratios, which is how all ancient astronomers' lunar motions were expressed. Long-eclipse-cycle-based reconstructions precisely produce all of the 24 digits appearing in the three attested ancient motions just cited: 6247 synod = 6695 anom (System A), 5458 synod = 5923 drac (Hipparchos), 3277 synod = 3512 anom (Planetary Hypotheses). By contrast, the System B motion, 251 synod = 269 anom (Aristarchos?), could have been determined without recourse to remote eclipse data, simply by using a few eclipse-pairs 4267 months apart.

- "Solar Eclipses in History and Mythology". Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Archived from the original on 2007-04-08. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Girault, Simon (1592). Globe dv monde contenant un bref traite du ciel & de la terra. Langres, France. p. Fol. 8V.

- Hevelius, Johannes (1652). Observatio Eclipseos Solaris Gedani. Danzig, Poland.

- Stephanson, Bruce; Bolt, Marvin; Friedman, Anna Felicity (2000). The Universe Unveiled: Instruments and Images through History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0521791434.

- "Roemer's Hypothesis". MathPages. Archived from the original on 2011-02-24. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Cassini, Giovanni D. (1694). "Monsieur Cassini His New and Exact Tables for the Eclipses of the First Satellite of Jupiter, Reduced to the Julian Stile, and Meridian of London". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 18 (207–214): 237–256. Bibcode:1694RSPT...18..237C. doi:10.1098/rstl.1694.0048. JSTOR 102468.

- Davidson, Norman (1985). Astronomy and the Imagination: A New Approach to Man's Experience of the Stars. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7102-0371-7.

- Buie, M. W.; Polk, K. S. (1988). "Polarization of the Pluto-Charon System During a Satellite Eclipse". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 20: 806. Bibcode:1988BAAS...20..806B.

- Tholen, D. J.; Buie, M. W.; Binzel, R. P.; Frueh, M. L. (1987). "Improved Orbital and Physical Parameters for the Pluto-Charon System". Science. 237 (4814): 512–514. Bibcode:1987Sci...237..512T. doi:10.1126/science.237.4814.512. PMID 17730324.

- Espenak, Fred (May 29, 2007). "Planetary Transits Across the Sun". NASA. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "When will the next transits of Mercury and Venus occur during a total solar eclipse? | Total Solar Eclipse 2017". eclipse2017.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- Bruton, Dan. "Eclipsing binary stars". Midnightkite Solutions. Archived from the original on 2007-04-14. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- Price, Aaron (January 1999). "Variable Star Of The Month: Beta Persei (Algol)". AAVSO. Archived from the original on 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- Goodricke, John; Englefield, H. C. (1785). "Observations of a New Variable Star". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 153–164. Bibcode:1785RSPT...75..153G. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eclipse. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Eclipse |

| Look up eclipse in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Eclipse (astronomy) at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Phobos Eclipsing Mars Observed by Curiosity Rover on YouTube

- A Catalogue of Eclipse Cycles

- Search 5,000 years of eclipses

- NASA eclipse home page

- International Astronomical Union's Working Group on Solar Eclipses

- Interactive eclipse maps site

- Classroom demonstration of how an eclipse occurs

- Image galleries

.jpg)