Charon (moon)

Charon (/ˈkɛərən/ or /ˈʃærən/), also known as (134340) Pluto I, is the largest of the five known natural satellites of the dwarf planet Pluto. It has a mean radius of 606 km (377 mi). Charon is the sixth-largest trans-Neptunian object after Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Gonggong.[17] It was discovered in 1978 at the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., using photographic plates taken at the United States Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station (NOFS).

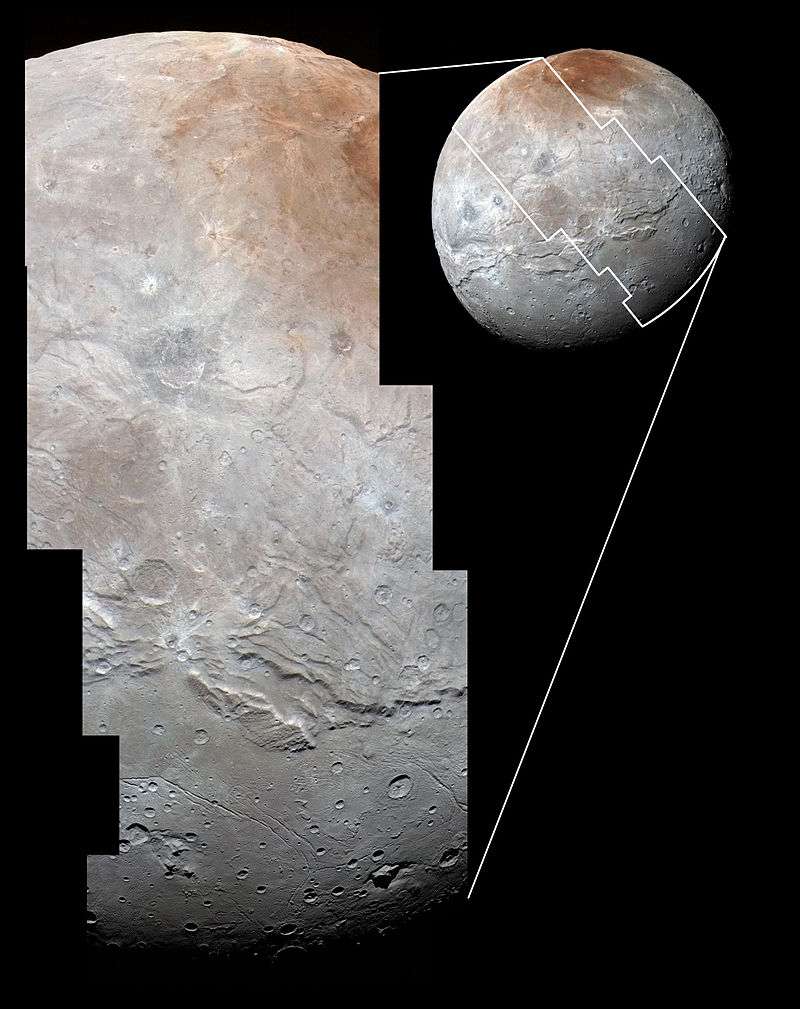

Charon in true color, imaged by New Horizons | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | James W. Christy |

| Discovery date | 22 June 1978 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Pluto I[1] |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɛərən/[2] or /ˈʃærən/[3] [note 1] |

Named after | Discoverer's wife, Charlene, and Χάρων Kharōn |

| S/1978 P 1 | |

| Adjectives | Charonian /kəˈroʊniən, ʃə-/[4][5] Charontian, -ean /kəˈrɒntiən/[6][7] Charonean /kærəˈniːən/[8] |

| Orbital characteristics [9] | |

| Epoch 2452600.5 (2002 Nov 22) | |

| Periapsis | 19,587 km |

| Apoapsis | 19,595 km |

| 19591.4 km (planetocentric)[10] 17181.0 km (barycentric) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0002[10] |

| 6.3872304±0.0000011 d (6 d, 9 h, 17 m, 36.7 ± 0.1 s) | |

Average orbital speed | 0.21 km/s[note 2] |

| Inclination | 0.080° (to Pluto's equator)[10] 119.591°±0.014° (to Pluto's orbit) 112.783°±0.014° (to the ecliptic) |

| 223.046°±0.014° (to vernal equinox) | |

| Satellite of | Pluto |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 606.0±0.5 km[11][12] (0.095 Earths, 0.51 Plutos) |

| Flattening | <0.5% [13] |

| 4.6×106 km2 (0.0090 Earths) | |

| Volume | (9.32±0.14)×108 km3 (0.00086 Earths) |

| Mass | (1.586±0.015)×1021 kg[11][12] (2.66×10−4 Earths) (12.2% of Pluto) |

Mean density | 1.702±0.017 g/cm3[12] |

| 0.288 m/s2 | |

| 0.59 km/s 0.37 mi/s | |

| synchronous | |

| Albedo | 0.2 to 0.5 at a solar phase angle of 15° |

| Temperature | −220 °C (53 K) |

| 16.8[14] | |

| 1[15] | |

| 55 milli-arcsec[16] | |

With half the diameter and one eighth the mass of Pluto, Charon is a very large moon in comparison to its parent body. Its gravitational influence is such that the barycenter of the Plutonian system lies outside Pluto.

The reddish-brown cap of the north pole of Charon is composed of tholins, organic macromolecules that may be essential ingredients of life. These tholins were produced from methane, nitrogen and related gases released from the atmosphere of Pluto and transferred over 19,000 km (12,000 mi) to the orbiting moon.[18]

The New Horizons spacecraft is the only probe that has visited the Pluto system. It approached Charon to within 27,000 km (17,000 mi) in 2015.

Discovery

Charon was discovered by United States Naval Observatory astronomer James Christy, using the 1.55-meter (61 in) telescope at United States Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station (NOFS).[19] On June 22, 1978, he had been examining highly magnified images of Pluto on photographic plates taken with the telescope two months prior. Christy noticed that a slight elongation appeared periodically. The bulge was confirmed on plates dating back to April 29, 1965.[20] The International Astronomical Union formally announced Christy's discovery to the world on July 7, 1978.[21]

Subsequent observations of Pluto determined that the bulge was due to a smaller accompanying body. The periodicity of the bulge corresponded to Pluto's rotation period, which was previously known from Pluto's light curve. This indicated a synchronous orbit, which strongly suggested that the bulge effect was real and not spurious. This resulted in reassessments of Pluto's size, mass, and other physical characteristics because the calculated mass and albedo of the Pluto–Charon system had previously been attributed to Pluto alone.

Doubts about Charon's existence were erased when it and Pluto entered a five-year period of mutual eclipses and transits between 1985 and 1990. This occurs when the Pluto–Charon orbital plane is edge-on as seen from Earth, which only happens at two intervals in Pluto's 248-year orbital period. It was fortuitous that one of these intervals happened to occur soon after Charon's discovery.

Name

Author Edmond Hamilton referred to three moons of Pluto in his 1940 science fiction novel Calling Captain Future, naming them Charon, Styx, and Cerberus.[23]

After its discovery, Charon was originally known by the temporary designation S/1978 P 1, according to the then recently instituted convention. On June 24, 1978, Christy first suggested the name Charon as a scientific-sounding version of his wife Charlene's nickname, "Char".[22][24] Although colleagues at the Naval Observatory proposed Persephone, Christy stuck with Charon after discovering that it coincidentally refers to a Greek mythological figure:[22] Charon (/ˈkɛərən/;[2] Greek Χάρων) is the ferryman of the dead, closely associated in myth with the god Hades or Plouton (Greek: Πλούτων, Ploútōn), whom the Romans identified with their god Pluto. The IAU officially adopted the name in late 1985 and it was announced on January 3, 1986.[25]

There is minor debate over the preferred pronunciation of the name. The practice of following the classical pronunciation established for the mythological ferryman Charon, with a "k" sound, is used by major English-language dictionaries, such as the Merriam-Webster and Oxford English dictionaries.[26][27] These indicate only the "k" pronunciation of "Charon" when referring specifically to Pluto's moon. Speakers of languages other than English, and many English-speaking astronomers as well, follow this pronunciation.[28]

However, Christy himself pronounced the initial ch as a "sh" sound (IPA /ʃ/), after his wife Charlene. Because of this, as an acknowledgement of Christy and sometimes as an in-joke or shibboleth, the initial "sh" pronunciation is common among astronomers when speaking English,[note 3][28][29][30] and this is the prescribed pronunciation at NASA and of the New Horizons team.[3][note 4]

Formation

Simulation work published in 2005 by Robin Canup suggested that Charon could have been formed by a collision around 4.5 billion years ago, much like Earth and the Moon. In this model, a large Kuiper belt object struck Pluto at high velocity, destroying itself and blasting off much of Pluto's outer mantle, and Charon coalesced from the debris.[31] However, such an impact should result in an icier Charon and rockier Pluto than scientists have found. It is now thought that Pluto and Charon might have been two bodies that collided before going into orbit about each other. The collision would have been violent enough to boil off volatile ices like methane (CH

4) but not violent enough to have destroyed either body. The very similar density of Pluto and Charon implies that the parent bodies were not fully differentiated when the impact occurred.[11]

Orbit

Charon and Pluto orbit each other every 6.387 days. The two objects are gravitationally locked to one another, so each keeps the same face towards the other. This is a case of mutual tidal locking, as compared to that of the Earth and the Moon, where the Moon always shows the same face to Earth, but not vice versa. The average distance between Charon and Pluto is 19,570 kilometres (12,160 mi). The discovery of Charon allowed astronomers to calculate accurately the mass of the Plutonian system, and mutual occultations revealed their sizes. However, neither indicated the two bodies' individual masses, which could only be estimated, until the discovery of Pluto's outer moons in late 2005. Details in the orbits of the outer moons revealed that Charon has approximately 12% of the mass of Pluto.[9]

Physical characteristics

Charon's diameter is 1,212 kilometres (753 mi), just over half that of Pluto.[11][12] Larger than the dwarf planet Ceres, it is the twelfth largest natural satellite in the Solar System. Charon's slow rotation means that there should be little flattening or tidal distortion, if Charon is sufficiently massive to be in hydrostatic equilibrium. Any deviation from a perfect sphere is too small to have been detected by observations by the New Horizons mission. This is in contrast to Iapetus, a Saturnian moon similar in size to Charon but with a pronounced oblateness dating to early in its history. The lack of such oblateness in Charon could mean that it is currently in hydrostatic equilibrium, or simply that its orbit approached its current one early in its history, when it was still warm.[13]

Based on mass updates from observations made by New Horizons[12] the mass ratio of Charon to Pluto is 0.1218:1. This is much larger than the Moon to the Earth: 0.0123:1. Because of the high mass ratio, the barycenter is outside of the radius of Pluto, and the Pluto-Charon system has been referred to as a dwarf double planet. With four smaller satellites in orbit about the two larger worlds, the Pluto-Charon system has been considered in studies of the orbital stability of circumbinary planets.[32]

Interior

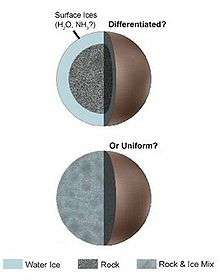

Charon's volume and mass allow calculation of its density, 1.702±0.017 g/cm3,[12] from which it can be determined that Charon is slightly less dense than Pluto and suggesting a composition of 55% rock to 45% ice (± 5%), whereas Pluto is about 70% rock. The difference is considerably lower than that of most suspected collisional satellites. Before New Horizons' flyby, there were two conflicting theories about Charon's internal structure: some scientists thought Charon to be a differentiated body like Pluto, with a rocky core and an icy mantle, whereas others thought it would be uniform throughout.[33] Evidence in support of the former position was found in 2007, when observations by the Gemini Observatory of patches of ammonia hydrates and water crystals on the surface of Charon suggested the presence of active cryogeysers. The fact that the ice was still in crystalline form suggested it had been deposited recently, because solar radiation would have degraded it to an amorphous state after roughly thirty thousand years.[34]

Surface

Unlike Pluto's surface, which is composed of nitrogen and methane ices, Charon's surface appears to be dominated by the less volatile water ice. In 2007, observations by the Gemini Observatory of patches of ammonia hydrates and water crystals on the surface of Charon suggested the presence of active cryogeysers and cryovolcanoes.[34][35]

Photometric mapping of Charon's surface shows a latitudinal trend in albedo, with a bright equatorial band and darker poles. The north polar region is dominated by a very large dark area informally dubbed "Mordor" by the New Horizons team.[36][37][38] The favored explanation for this phenomenon is that they are formed by condensation of gases that escaped from Pluto's atmosphere. In winter, the temperature is −258 °C, and these gases, which include nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane, condense into their solid forms; when these ices are subjected to solar radiation, they chemically react to form various reddish tholins. Later, when the area is again heated by the Sun as Charon's seasons change, the temperature at the pole rises to −213 °C, resulting in the volatiles sublimating and escaping Charon, leaving only the tholins behind. Over millions of years, the residual tholin builds up thick layers, obscuring the icy crust.[39] In addition to Mordor, New Horizons found evidence of extensive past geology that suggests that Charon is probably differentiated;[37] in particular, the southern hemisphere has fewer craters than the northern and is considerably less rugged, suggesting that a massive resurfacing event—perhaps prompted by the partial or complete freezing of an internal ocean—occurred at some point in the past and removed many of the earlier craters.[40]

In 2018, the International Astronomical Union named one crater on Charon, as Revati who is a character in the Hindu epic Mahabharata.[41][42]

Charon has a series of extensive grabens or canyons, such as Serenity Chasma, which extend as an equatorial belt for at least 1,000 km (620 mi). Argo Chasma potentially reaches as deep as 9 km (6 mi), with steep cliffs that may rival Verona Rupes on Miranda for the title of tallest cliff in the solar system.[43]

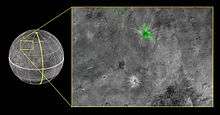

Mountain in a moat

In a released photo by New Horizons, an unusual surface feature has captivated and baffled the scientist team of the mission. The image reveals a mountain rising out of a depression. It's "a large mountain sitting in a moat", said Jeff Moore, of NASA's Ames Research Center, in a statement. "This is a feature that has geologists stunned and stumped", he added. New Horizons captured the photo from a distance of 79,000 km (49,000 mi).[44][45]

Observation and exploration

Since the first blurred images of the moon (1), images showing Pluto and Charon resolved into separate disks were taken for the first time by the Hubble Space Telescope in the 1990s (2). The telescope was responsible for the best, yet low quality images of the moon. In 1994, the clearest picture of the Pluto-Charon system showed two distinct and well defined circles (3). The image was taken by Hubble's Faint Object Camera (FOC) when the system was 4.4 billion kilometers (2.6 billion miles) away from Earth[46] Later, the development of adaptive optics made it possible to resolve Pluto and Charon into separate disks using ground-based telescopes.[24]

In June 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft captured consecutive images of the Pluto–Charon system as it approached it. The images were put together in an animation. It was the best image of Charon to that date (4). In July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft made its closest approach to the Pluto system. It is the only spacecraft to date to have visited and studied Charon. Charon's discoverer James Christy and the children of Clyde Tombaugh were guests at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory during the New Horizons closest approach.

Classification

The center of mass (barycenter) of the Pluto–Charon system lies outside either body. Because neither object truly orbits the other, and Charon has 12.2% the mass of Pluto, it has been argued that Charon should be considered to be part of a binary system with Pluto. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) states that Charon is considered to be just a satellite of Pluto, but the idea that Charon might be classified a dwarf planet in its own right may be considered at a later date.[47]

In a draft proposal for the 2006 redefinition of the term, the IAU proposed that a planet be defined as a body that orbits the Sun that is large enough for gravitational forces to render the object (nearly) spherical. Under this proposal, Charon would have been classified as a planet, because the draft explicitly defined a planetary satellite as one in which the barycenter lies within the major body. In the final definition, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet, but the formal definition of a planetary satellite was not decided upon. Charon is not in the list of dwarf planets currently recognized by the IAU.[47] Had the draft proposal been accepted, even the Moon would be classified as a planet in billions of years when the tidal acceleration that is gradually moving the Moon away from Earth takes it far enough away that the center of mass of the system no longer lies within Earth.[48]

The other moons of Pluto–Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx–orbit the same barycenter but they are not large enough to be spherical and they are simply considered to be satellites of Pluto (or of Pluto–Charon).[49]

Gallery

Global map of Charon in enhanced color

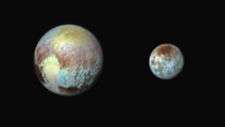

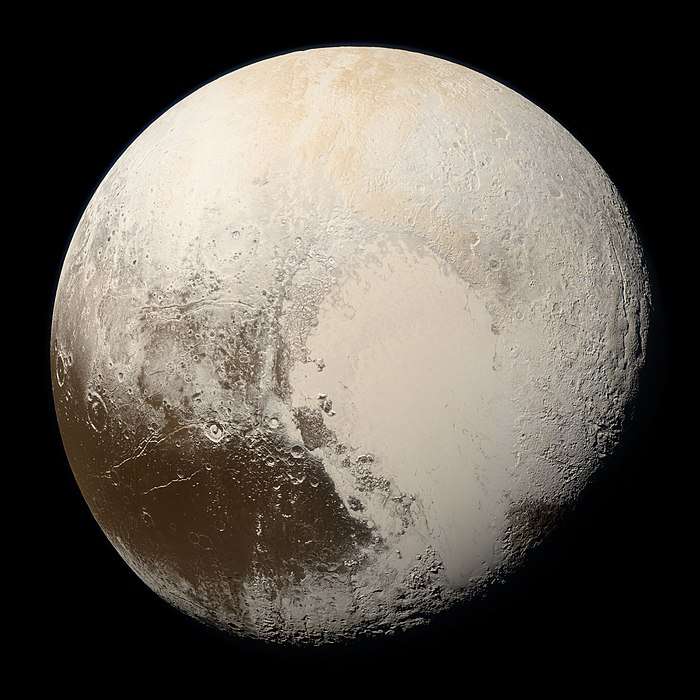

Global map of Charon in enhanced color Identically processed enhanced color views of Pluto and Charon

Identically processed enhanced color views of Pluto and Charon High resolution enhanced color mosaic of Charon

High resolution enhanced color mosaic of Charon Pluto and Charon, to scale. Viewed by New Horizons on approach.

Pluto and Charon, to scale. Viewed by New Horizons on approach. Pluto and Charon as viewed by New Horizons

Pluto and Charon as viewed by New Horizons

(color; July 11, 2015). Pluto and Charon as viewed by New Horizons

Pluto and Charon as viewed by New Horizons

(false-color; July 13, 2015). Charon – night-side as viewed by New Horizons

Charon – night-side as viewed by New Horizons

(July 17, 2015).

Videos

See also

Notes

- The former is the anglicized pronunciation of the Greek: Χάρων, the latter is the discoverer's pronunciation.

- Calculated on the basis of other parameters.

- Astronomer Mike Brown can be heard pronouncing it [ˈʃɛɹᵻn] in ordinary conversation on the KCET interview ["Julia Sweeney and Michael E. Brown". Hammer Conversations: KCET podcast. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-01.] at 42min 48sec. Being a long-time resident of California, he does not distinguish the /ær/ vowel of the name Sharon and the /ɛər/ vowel of the classical pronunciation of Charon.

- Hal Weaver, who led the team that discovered Nix and Hydra, also pronounces it [ˈʃɛɹ

ɪn] (/ˈʃærən/ with a generic American accent) on the Discovery Science Channel documentary Passport to Pluto, premiered 2006-01-15.

References

- Jennifer Blue (2009-11-09). "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature". IAU Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- "Charon". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Pronounced "Sharon" /ˈʃærən/ per "NASA New Horizons: The PI's Perspective—Two for the Price of One". Retrieved 2008-10-03. and per "New Horizons Team Names Science Ops Center After Charon's Discoverer". Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- C.T. Russell (2009) New Horizons: Reconnaissance of the Pluto–Charon System and the Kuiper Belt, p. 96

- Kathryn Bosher (2012) Theater outside Athens: Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy, pp 100, 104–105

- Bowman et al. (1979) Studies in Honor of Gerald E. Wade, p. 125–126

- William Herbert (1838) Attila, King of the Huns, p.48

- Explicitly from the adjective Charōnēus. Tatiana Kontou (2009) Spiritualism and Women's Writing: From the Fin de Siècle to the Neo-Victorian, p. 60 ff

- Buie, Marc W.; Grundy, William M.; Young, Eliot F.; Young, Leslie A.; Stern, S. Alan (5 Jun 2006). "Orbits and Photometry of Pluto's Satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 290–298. arXiv:astro-ph/0512491. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..290B. doi:10.1086/504422.

- "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters — Satellites of Pluto". Solar System Dynamics. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- Stern, S.A.; Bagenal, F.; Ennico, K.; Gladstone, G.R.; Grundy, W.M.; McKinnon, W.B.; Moore, J.M.; Olkin, C.B.; Spencer, J.R. (16 Oct 2015). "The Pluto system: Initial results from its exploration by New Horizons". Science. 350 (6258): aad1815. arXiv:1510.07704. Bibcode:2015Sci...350.1815S. doi:10.1126/science.aad1815. PMID 26472913.

- Stern, S.A.; Grundy, W.; McKinnon, W.B.; Weaver, H.A.; Young, L.A. (15 Dec 2017). "The Pluto System After New Horizons". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 56: 357–392. arXiv:1712.05669. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-051935.

- Nimmo, F.; Umurhan, O.; Lisse, C.M.; Bierson, C.J.; Lauer, T.R.; Buie, M.W.; Throop, H.B.; Kammer, J.A.; Roberts, J.H.; McKinnon, W.B.; Zangari, A.M.; Moore, J.M.; Stern, S.A.; Young, L.A.; Weaver, H.A.; Olkin, C.B.; Ennico, K.; and the New Horizons GGI team (1 May 2017). "Mean radius and shape of Pluto and Charon from New Horizons images". Icarus. 287: 12–29. arXiv:1603.00821. Bibcode:2017Icar..287...12N. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.06.027.

- "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. April 15, 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- David Jewitt (June 2008). "The 1000 km Scale KBOs". Institute for Astronomy (UH). Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- "Measuring the Size of a Small, Frost World" (Press release). European Southern Observatory. 2006-01-04. Archived from the original on 2006-01-18. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/astro/tnos.html#LAR

- Bromwich, Jonah Engel; St. Fleur, Nicholas (14 September 2016). "Why Pluto's Moon Charon Wears a Red Cap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- "Charon Discovery Image". Solar System Exploration. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 16 December 2003. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Dick, Steven J. (2013). "The Pluto Affair". Discovery and Classification in Astronomy: Controversy and Consensus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-1-107-03361-0.

- "IAUC 3241: 1978 P 1; 1978 (532) 1; 1977n". Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. July 7, 1978. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Shilling, Govert (June 2008). "A Bump in the Night". Sky & Telescope. pp. 26–27. Prior to this, Christy had considered naming the moon Oz.

- Codex Regius (2016). Pluto & Charon. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1534960749.

- Williams, Matt (14 Jul 2015). "Charon: Pluto's Largest Moon". Universe Today. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- "IAUC 4157: CH Cyg; R Aqr; Sats OF SATURN AND PLUTO". Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. January 3, 1986. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "Charon". Dictionary.com.

- "Charon". Oxford English Dictionary.

- Pronounced "KAIR en" or "SHAHR en" per "Pluto Facts". Nine Planets. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- Pronounced 'with a soft "sh" ' per "Welcome to the solar system, Nix and Hydra!". The Planetary Society Weblog. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- US Naval Observatory spokesman Jeff Chester, when interviewed on the NPR commentary "Letters: Radiology Dangers, AIDS, Charon". Morning Edition. 2006-01-19. Retrieved 2008-10-03. (at 2min 49sec), says Christy pronounced it [ˈʃɛɹɒn] rather than classical [ˈkɛɹɒn]. In normal conversation, the second vowel is reduced to a schwa: /ˈkɛərən/ in RP (ref: OED).

- Canup, Robin (January 28, 2005). "A Giant Impact Origin of Pluto–Charon". Science. 307 (5709): 546–50. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..546C. doi:10.1126/science.1106818. PMID 15681378.

- Sutherland, A.P.; Kratter, K.M. (29 May 2019). "Instabilities in Multi-Planet Circumbinary Systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 487 (3): 3288–3304. arXiv:1905.12638. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.487.3288S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz1503.

- "Charon". Planetsedu.com. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- "Charon: An ice machine in the ultimate deep freeze". Gemini Observatory. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- Cook; Desch, Steven J.; Roush, Ted L.; Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Geballe, T. R. (2007). "Near-Infrared Spectroscopy of Charon: Possible Evidence for Cryovolcanism on Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astrophysical Journal. 663 (2): 1406–1419. Bibcode:2007ApJ...663.1406C. doi:10.1086/518222.

- "The New Horizons team refers to a dark patch on Pluto's moon as 'Mordor'". The Week. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- "New Horizons Photos Show Pluto's Ice Mountains and Charon's Huge Crater". NBC News. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- Corum, Jonathan (15 July 2015). "New Horizons Reveals Ice Mountains on Pluto". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- Howett, Carley (11 September 2015). "New Horizons probes the mystery of Charon's red pole". Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- Beatty, Kelly (2 October 2015). "Charon: Cracked, Cratered, and Colorful". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/naming-crater-pluto-s-largest-moon-revati-astronomers-honour-india-79705

- "Hindus welcome naming crater on Pluto's largest moon Charon after Revati - News Patrolling". Dailyhunt.

- Keeter, Bill (2016-06-23). "A 'Super Grand Canyon' on Pluto's Moon Charon". NASA. Retrieved 2017-08-03.

- "Pluto's Big Moon Charon Has a Bizarre Mountain in a Moat (Photo)". Space.com. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- "Mysterious Mountain Revealed in First Close-up of Pluto's Moon Charon". Universe Today. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- "Pluto and Charon". Hubble Space Telescope. 16 May 1994. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- "Pluto and the Developing Landscape of Our Solar System". IAU. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Robert Roy Britt (2006-08-18). "Earth's moon could become a planet". CNN Science & Space. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- Stern, Alan; Weaver, Hal; Mutchler, Max; Steffl, Andrew; Merline, Bill; Buie, Marc; Spencer, John; Young, Eliot; Young, Leslie (2005-05-15). "Background Information Regarding Our Two Newly Discovered Satellites of Pluto". Planetary Science Directorate. Southwest Research Institute, Boulder Office. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charon (moon). |

- Charon Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Christy, J. W; Harrington, R. S (1978). "The satellite of Pluto". Astronomical Journal. 83: 1005. Bibcode:1978AJ.....83.1005C. doi:10.1086/112284. S2CID 120501620.

- Hubble reveals new map of Pluto, BBC News, September 12, 2005

- Person, M. J; Elliot, J. L; Gulbis, A. A. S; Pasachoff, J. M; Babcock, B. A; Souza, S. P; Gangestad, J (2006). "Charon's radius and density from the combined data sets of the 2005 July 11 occultation". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (4): 1575–1580. arXiv:astro-ph/0602082. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.1575P. doi:10.1086/507330.

- Cryovolcanism on Charon and other Kuiper Belt Objects

- New Horizons Camera Spots Pluto’s Largest Moon – July 10, 2013

- New Horizons in the PHSF clean room at KSC, Nov 4, 2005

- 40th anniversary NASA video describing the discovery and naming of Charon (22 June 2018)

- NASA CGI video of Charon flyover (14 July 2017)

- CGI video simulation of rotating Charon by Seán Doran (see album for more)

- Google Charon 3D, interactive map of the moon

- "2016 Lunar & Planetary Science Conference by National Institute of Aerospace".

- Interactive 3D gravity simulation of Pluto and Charon in addition to Pluto's four other moons Styx, Kerberos, Hydra and Nix

_(cropped).jpg)