Cult

In modern English, a cult is a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs, or by its common interest in a particular personality, object or goal. This sense of the term is controversial, having divergent definitions both in popular culture and academia, and has also been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study.[1][2]:348–56 It is usually considered pejorative.

An older description of the word cult is a set of religious devotional practices that are conventional within their culture, are related to a particular figure, and are often associated with a particular place. References to the "cult" of a particular Catholic saint, or the imperial cult of ancient Rome, for example, use this sense of the word.

While the literal and original sense of the word remains in use in the English language, a derived sense of "excessive devotion" arose in the 19th century.[lower-roman 1] Beginning in the 1930s, cults became the object of sociological study in the context of the study of religious behaviour.[3] From the 1940s the Christian countercult movement has opposed some sects and new religious movements, and it labelled them as cults for their "un-Christian" unorthodox beliefs. The secular anti-cult movement began in the 1970s and it opposed certain groups, often charging them with mind control and partly motivated in reaction to acts of violence committed by some of their members. Some of the claims and actions of the anti-cult movement have been disputed by scholars and by the news media, leading to further public controversy.

In the sociological classifications of religious movements, a cult is a social group with socially deviant or novel beliefs and practices,[4] although this is often unclear.[5][6][7] Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.[8] Groups which are said to be cults range in size from local groups with a few members to international organizations with millions of members.[9]

Definition

In the English-speaking world, the term cult often carries derogatory connotations.[10] In this sense, it has been considered a subjective term, used as an ad hominem attack against groups with differing doctrines or practices.[6][11] As such, religion scholar Megan Goodwin defined the term cult, when used by the layperson, as often being a shorthand for a "religion I don't like."[12]

In the 1970s, with the rise of secular anti-cult movements, scholars (though not the general public) began abandoning the term cult. According to The Oxford Handbook of Religious Movements, "by the end of the decade, the term 'new religions' would virtually replace 'cult' to describe all of those leftover groups that did not fit easily under the label of church or sect."[13]

Sociologist Amy Ryan (2000) has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign.[14] Ryan notes the sharp differences between definitions offered by cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and those offered by sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. The movements themselves may have different definitions of religion as well.[15] George Chryssides also cites a need to develop better definitions to allow for common ground in the debate. Casino (1999) presents the issue as crucial to international human rights laws. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."[16]

New religious movements

A new religious movement (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations.[17][18] In 1999, Eileen Barker estimated that NRMs, of which some but not all have been labelled as cults, number in the tens of thousands worldwide, most of which originated in Asia or Africa; and that the great majority of which have only a few members, some have thousands and only very few have more than a million.[9] In 2007, religious scholar Elijah Siegler commented that, although no NRM had become the dominant faith in any country, many of the concepts which they had first introduced (often referred to as "New Age" ideas) have become part of worldwide mainstream culture.[18]:51

Scholarly studies

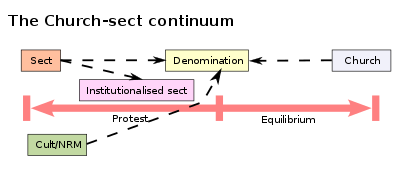

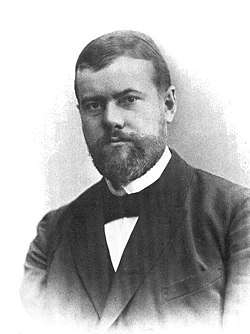

Sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) found that cults based on charismatic leadership often follow the routinization of charisma.[19] The concept of a cult as a sociological classification, however, was introduced in 1932 by American sociologist Howard P. Becker as an expansion of German theologian Ernst Troeltsch's church–sect typology. Troeltsch's aim was to distinguish between three main types of religious behaviour: churchly, sectarian, and mystical.

Becker further bisected Troeltsch's first two categories: church was split into ecclesia and denomination; and sect into sect and cult.[20] Like Troeltsch's "mystical religion," Becker's cult refers to small religious groups that lack in organization and emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs.[21] Later sociological formulations built on such characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as deviant religious groups, "deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture."[2]:349 This is often thought to lead to a high degree of tension between the group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it, a characteristic shared with religious sects.[22] According to this sociological terminology, sects are products of religious schism and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, whereas cults arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.[23]

In the early 1960s, sociologist John Lofland, living with South Korean missionary Young Oon Kim and some of the first American Unification Church members in California, studied their activities in trying to promote their beliefs and win new members.[24] Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members, often family relationships.[25] Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a doctoral thesis entitled "The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book form by Prentice-Hall as Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization and Maintenance of Faith. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.[26][27]

Sociologist Roy Wallis (1945–1990) argued that a cult is characterized by "epistemological individualism," meaning that "the cult has no clear locus of final authority beyond the individual member." Cults, according to Wallis, are generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals, loosely structured, tolerant [and] non-exclusive," making "few demands on members," without possessing a "clear distinction between members and non-members," having "a rapid turnover of membership" and as being transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief systems. Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu."[28]

In 1978, Bruce Campbell noted that cults are associated with beliefs in a divine element in the individual; it is either soul, self, or true self. Cults are inherently ephemeral and loosely organized. There is a major theme in many of the recent works that show the relationship between cults and mysticism. Campbell, describing cults as non-traditional religious groups based on belief in a divine element in the individual, brings two major types of such to attention—mystical and instrumental—dividing cults into either occult or metaphysical assembly. There is also a third type, the service-oriented, as Campbell states that "the kinds of stable forms which evolve in the development of religious organization will bear a significant relationship to the content of the religious experience of the founder or founders."[29]

Dick Anthony, a forensic psychologist known for his criticism of brainwashing theory of conversion,[30][31][32] has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful effects, saying that "[t]here's a large research literature published in mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's measurable."[33]

In their 1996 book Theory of Religion, American sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge propose that the formation of cults can be explained through the rational choice theory.[34] In The Future of Religion they comment that, "in the beginning, all religions are obscure, tiny, deviant cult movements."[35] According to Marc Galanter, Professor of Psychiatry at NYU, typical reasons why people join cults include a search for community and a spiritual quest.[36] Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals join new religious groups, have even questioned the utility of the concept of conversion, suggesting that affiliation is a more useful concept.[37]

J. Gordon Melton stated that, in 1970, "one could count the number of active researchers on new religions on one's hands." However, James R. Lewis writes that the "meteoric growth" in this field of study can be attributed to the cult controversy of the early 1970s, when news stories about the Peoples Temple and Heaven's Gate were being reported. Because of "a wave of nontraditional religiosity" in the late 1960s and early 1970s, academics perceived new religious movements as different phenomena from previous religious innovations.[38]

Anti-cult movements

Christian countercult movement

In the 1940s, the long-held opposition by some established Christian denominations to non-Christian religions and supposedly heretical or counterfeit Christian sects crystallized into a more organized Christian countercult movement in the United States. For those belonging to the movement, all religious groups claiming to be Christian, but deemed outside of Christian orthodoxy, were considered cults.[39] Christian cults are new religious movements which have a Christian background but are considered to be theologically deviant by members of other Christian churches.[40] In his influential book The Kingdom of the Cults (1965), Christian scholar Walter Martin defines Christian cults as groups that follow the personal interpretation of an individual, rather than the understanding of the Bible accepted by Nicene Christianity, providing the examples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Christian Science, Jehovah's Witnesses, and the Unity Church.[41]:18

The Christian countercult movement asserts that Christian sects whose beliefs are partially or wholly not in accordance with the Bible are erroneous. It also states that a religious sect can be considered a cult if its beliefs involve a denial of what they view as any of the essential Christian teachings such as salvation, the Trinity, Jesus himself as a person, the ministry of Jesus, the miracles of Jesus, the crucifixion, the resurrection of Christ, the Second Coming, and the rapture.[42][43][44]

Countercult literature usually expresses doctrinal or theological concerns and a missionary or apologetic purpose.[45] It presents a rebuttal by emphasizing the teachings of the Bible against the beliefs of non-fundamental Christian sects. Christian countercult activist writers also emphasize the need for Christians to evangelize to followers of cults.[46][47][41]:479–93

Secular anti-cult movement

In the early 1970s, a secular opposition movement to groups considered cults had taken shape. The organizations that formed the secular anti-cult movement (ACM) often acted on behalf of relatives of "cult" converts who did not believe their loved ones could have altered their lives so drastically by their own free will. A few psychologists and sociologists working in this field suggested that brainwashing techniques were used to maintain the loyalty of cult members.[48] The belief that cults brainwashed their members became a unifying theme among cult critics and in the more extreme corners of the anti-cult movement techniques like the sometimes forceful "deprogramming" of cult members was practised.[49]

Secular cult opponents belonging to the anti-cult movement usually define a "cult" as a group that tends to manipulate, exploit, and control its members. Specific factors in cult behaviour are said to include manipulative and authoritarian mind control over members, communal and totalistic organization, aggressive proselytizing, systematic programs of indoctrination, and perpetuation in middle-class communities.[50][51][52][53][54][55] In the mass media, and among average citizens, "cult" gained an increasingly negative connotation, becoming associated with things like kidnapping, brainwashing, psychological abuse, sexual abuse and other criminal activity, and mass suicide. While most of these negative qualities usually have real documented precedents in the activities of a very small minority of new religious groups, mass culture often extends them to any religious group viewed as culturally deviant, however peaceful or law abiding it may be.[56][57][58][2]:348–56

While some psychologists were receptive to these theories, sociologists were for the most part sceptical of their ability to explain conversion to NRMs.[59] In the late 1980s, psychologists and sociologists started to abandon theories like brainwashing and mind-control. While scholars may believe that various less dramatic coercive psychological mechanisms could influence group members, they came to see conversion to new religious movements principally as an act of a rational choice.[60][61]

Reactions to the anti-cult movements

Because of the increasingly pejorative use of the words "cult" and "cult leader" since the cult debate of the 1970s, some academics, in addition to groups referred to as cults, argue that these are words to be avoided.[62][2]:348–56 Catherine Wessinger (Loyola University New Orleans) has stated that the word "cult" represents just as much prejudice and antagonism as racial slurs or derogatory words for women and homosexuals.[63] She has argued that it is important for people to become aware of the bigotry conveyed by the word, drawing attention to the way it dehumanizes the group's members and their children.[63] Labelling a group as subhuman, she says, becomes a justification for violence against it.[63] She also says that labelling a group a "cult" makes people feel safe, because the "violence associated with religion is split off from conventional religions, projected onto others, and imagined to involve only aberrant groups."[63] This fails to take into account that child abuse, sexual abuse, financial extortion and warfare have also been committed by believers of mainstream religions, but the pejorative "cult" stereotype makes it easier to avoid confronting this uncomfortable fact.[63]

Subcategories

Destructive cults

Destructive cult generally refers to groups whose members have, through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the general public."[64] Psychologist Michael Langone, executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association, defines a destructive cult as "a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits."[65]

John Gordon Clark cited totalitarian systems of governance and an emphasis on money making as characteristics of a destructive cult.[66] In Cults and the Family, the authors cite Shapiro, who defines a destructive cultism as a sociopathic syndrome, whose distinctive qualities include: "behavioral and personality changes, loss of personal identity, cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders."[67]

In the opinion of Sociology Professor Benjamin Zablocki of Rutgers University, destructive cults are at high risk of becoming abusive to members, stating that such is in part due to members' adulation of charismatic leaders contributing to the leaders becoming corrupted by power.[68] According to Barrett, the most common accusation made against destructive cults is sexual abuse. According to Kranenborg, some groups are risky when they advise their members not to use regular medical care.[69] This may extend to physical and psychological harm.[70]

Writing about Bruderhof communities in the book Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field, Julius H. Rubin said that American religious innovation created an unending diversity of sects. These "new religious movements…gathered new converts and issued challenges to the wider society. Not infrequently, public controversy, contested narratives and litigation result."[1] In his work Cults in Context author Lorne L. Dawson writes that although the Unification Church "has not been shown to be violent or volatile," it has been described as a destructive cult by "anticult crusaders."[71] In 2002, the German government was held by the Federal Constitutional Court to have defamed the Osho movement by referring to it, among other things, as a "destructive cult" with no factual basis.[72][73]

Some researchers have criticized the usage of the term destructive cult, writing that it is used to describe groups which are not necessarily harmful in nature to themselves or others. In his book Understanding New Religious Movements, John A. Saliba writes that the term is overgeneralized. Saliba sees the Peoples Temple as the "paradigm of a destructive cult", where those that use the term are implying that other groups will also commit mass suicide.[74]

Doomsday cults

Doomsday cult is an expression which is used to describe groups that believe in Apocalypticism and Millenarianism, and it can also be used to refer both to groups that predict disaster, and groups that attempt to bring it about.[75] In the 1950s, American social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues observed members of a small UFO religion called the Seekers for several months, and recorded their conversations both prior to and after a failed prophecy from their charismatic leader.[76][77][78] Their work was later published in the book When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World.[79] In the late 1980s, doomsday cults were a major topic of news reports, with some reporters and commentators considering them a serious threat to society.[80] A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter found that people turned to a cataclysmic world view after they had repeatedly failed to find meaning in mainstream movements.[81] People also strive to find meaning in global events such as the turn of the millennium when many predicted it prophetically marked the end of an age and thus the end of the world.[58] An ancient Mayan calendar ended at the year 2012 and many anticipated catastrophic disasters would rock the Earth.[82]

Political cults

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and ideology.[83][84] Groups which some writers have termed "political cults", mostly advocating far-left or far-right agendas, have received some attention from journalists and scholars. In their 2000 book On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left, Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that they characterize as cults.[83][85] In a separate article, Tourish says that in his usage:[86]

The word cult is not a term of abuse, as this paper tries to explain. It is nothing more than a shorthand expression for a particular set of practices that have been observed in a variety of dysfunctional organisations.

The Iron Guard movement of interwar Romania, ruling the nation for a short time,[87] has been referred to as a "macabre political cult,"[88] a cargo cult[89] and a "cult of martyrdom and violence."[90]

Followers of Ayn Rand have been characterized as a cult by economist Murray N. Rothbard during her lifetime, and later by Michael Shermer.[91][92][93] The core group around Rand was called the "Collective," which are now defunct; the chief group disseminating Rand's ideas today is the Ayn Rand Institute. Although the Collective advocated an individualist philosophy, Rothbard claimed they were organized in the manner of a "Leninist" organization.[91]

The LaRouche Movement[94] and Gino Perente's National Labor Federation (NATLFED)[95] are examples of political groups that have been described as "cults," based in the United States, as well as Marlene Dixon's now-defunct Democratic Workers Party. (A critical history of the DWP is given in Bounded Choice by Janja Lalich, a sociologist and former DWP member.)[96]

In Britain, the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), a Trotskyist group led by Gerry Healy and strongly supported by actress Vanessa Redgrave, has been described by others, who have been involved in the Trotskyist movement, as having been a cult or as displaying cult-like characteristics in the 1970s and 1980s.[97] It is also described as such by Wohlforth and Tourish,[98] to whom Bob Pitt, a former member of the WRP, concedes that it had a "cult-like character" though arguing that rather than being typical of the far left, this feature actually made the WRP atypical and "led to its being treated as a pariah within the revolutionary left itself."[99] Lutte Ouvrière (LO; "Workers' Struggle") in France, publicly headed by Arlette Laguiller but revealed in the 1990s to be directed by Robert Barcia, has often been criticized as a cult, for example, by Daniel Cohn-Bendit and his older brother Gabriel Cohn-Bendit, as well as by L'Humanité and Libération.[100]

In his book Les Sectes Politiques: 1965–1995 ("Political cults: 1965–1995"), French writer Cyril Le Tallec considers some religious groups as cults involved in politics, including the League for Catholic Counter-Reformation, the Cultural Office of Cluny, New Acropolis, Sōka Gakkai, the Divine Light Mission, Tradition Family Property (TFP), Longo Maï, the Supermen Club, and the Association for Promotion of the Industrial Arts (Solazaref).[101]

In 1990, Lucy Patrick commented:[102]

Although we live in a democracy, cult behavior manifests itself in our unwillingness to question the judgment of our leaders, our tendency to devalue outsiders and to avoid dissent. We can overcome cult behavior, he says, by recognizing that we have dependency needs that are inappropriate for mature people, by increasing anti-authoritarian education, and by encouraging personal autonomy and the free exchange of ideas.

Polygamist cults

Cults that teach and practice polygamy, marriage between more than two people, most often polygyny, one man having multiple wives, have long been noted, although they are a minority. It has been estimated that there are around 50,000 members of polygamist cults in North America.[103] Often, polygamist cults are viewed negatively by both legal authorities and society, and this view sometimes includes negative perceptions of related mainstream denominations, because of their perceived links to possible domestic violence and child abuse.[104]

In 1890, the president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), Wilford Woodruff, issued a public declaration (the Manifesto) announcing that the LDS Church had ceased performing new plural marriages. Anti-Mormon sentiment waned, as did opposition to statehood for Utah. The Smoot Hearings in 1904, which documented that the LDS Church was still practising polygamy spurred the church to issue a Second Manifesto again claiming that it had ceased performing new plural marriages. By 1910 the LDS Church excommunicated those who entered into or performed new plural marriages.[105] Enforcement of the 1890 Manifesto caused various splinter groups to leave the LDS Church in order to continue the practice of plural marriage.[106] The Church of Jesus Christ Restored is a small sect within the Latter Day Saint movement based in Chatsworth, Ontario, Canada. It has been labelled a polygamous cult by the news media and has been the subject of criminal investigation by local authorities.[107][108][109]

Racist cults

Sociologist and historian Orlando Patterson has described the Ku Klux Klan, which arose in the American South after the Civil War, as a heretical Christian cult, and he has also described its persecution of African Americans and others as a form of human sacrifice.[110] Secret Aryan cults in Germany and Austria in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a strong influence on the rise of Nazism.[111] Modern white power skinhead groups in the United States tend to use the same recruitment techniques as destructive cults.[112]

Terrorist cults

In the book Jihad and Sacred Vengeance: Psychological Undercurrents of History, psychiatrist Peter A. Olsson compares Osama bin Laden to certain cult leaders including Jim Jones, David Koresh, Shoko Asahara, Marshall Applewhite, Luc Jouret and Joseph Di Mambro, and he says that each of these individuals fit at least eight of the nine criteria for people with narcissistic personality disorders.[113] In the book Seeking the Compassionate Life: The Moral Crisis for Psychotherapy and Society authors Goldberg and Crespo also refer to Osama bin Laden as a "destructive cult leader."[114]

At a 2002 meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), anti-cultist Steven Hassan said that Al-Qaida fulfills the characteristics of a destructive cult, adding, in addition:[115]

We need to apply what we know about destructive mind-control cults, and this should be a priority in the War on Terrorism. We need to understand the psychological aspects of how people are recruited and indoctrinated so we can slow down recruitment. We need to help counsel former cult members and possibly use some of them in the war against terrorism.

In an article on Al-Qaida published in The Times, journalist Mary Ann Sieghart wrote that al-Qaida resembles a "classic cult:"[116]

Al-Qaida fits all the official definitions of a cult. It indoctrinates its members; it forms a closed, totalitarian society; it has a self-appointed, messianic and charismatic leader; and it believes that the ends justify the means.

Similar to Al-Qaida, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant adheres to an even more extremist and puritanical ideology, in which the goal is to create a state governed by shari'ah as interpreted by its religious leadership, who then brainwash and command their able-bodied male subjects to go on suicide missions, with such devices as car bombs, against its enemies, including deliberately-selected civilian targets, such as churches and Shi'ite mosques, among others. Subjects view this as a legitimate action; an obligation, even. The ultimate goal of this political-military endeavour is to eventually usher in the Islamic end times and have the chance to participate in their version of the apocalyptic battle, in which all of their enemies (i.e. anyone who is not on their side) would be annihilated.[117] Such endeavour ultimately failed in 2017,[118] though hardcore survivors have largely returned to insurgency terrorism (i.e., Iraqi insurgency, 2017–present). The People's Mujahedin of Iran, a leftist guerrilla movement based in Iraq, has controversially been described as both a political cult and a movement that is abusive towards its own members.[119][120][121][122] Former Mujaheddin member and now-author and academic Dr. Masoud Banisadr stated in a May 2005 speech in Spain:[123]

If you ask me: are all cults a terrorist organisation? My answer is no, as there are many peaceful cults at present around the world and in the history of mankind. But if you ask me are all terrorist organisations some sort of cult, my answer is yes. Even if they start as [an] ordinary modern political party or organisation, to prepare and force their members to act without asking any moral questions and act selflessly for the cause of the group and ignore all the ethical, cultural, moral or religious codes of the society and humanity, those organisations have to change into a cult. Therefore to understand an extremist or a terrorist organisation one has to learn about a cult.

In 2003, the group ordered some of its members to set themselves on fire, two of whom died.[124]

The Shining Path guerrilla movement, active in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, has variously been described as a "cult"[125] and an intense "cult of personality."[126] The Tamil Tigers have also been described as such by the French magazine L'Express.[127]

Governmental policies and actions

The application of the labels "cult" or "sect" to religious movements in government documents signifies the popular and negative use of the term "cult" in English and a functionally similar use of words translated as "sect" in several European languages.[128] Sociologists critical to this negative politicized use of the word "cult" argue that it may adversely impact the religious freedoms of group members.[129] At the height of the counter-cult movement and ritual abuse scare of the 1990s, some governments published lists of cults.[lower-roman 2] While these documents utilize similar terminology they do not necessarily include the same groups nor is their assessment of these groups based on agreed criteria.[128] Other governments and world bodies also report on new religious movements but do not use these terms to describe the groups.[128] Since the 2000s, some governments have again distanced themselves from such classifications of religious movements.[lower-roman 3] While the official response to new religious groups has been mixed across the globe, some governments aligned more with the critics of these groups to the extent of distinguishing between "legitimate" religion and "dangerous," "unwanted" cults in public policy.[48][130]

China

For centuries, governments in China have categorized certain religions as xiéjiào (邪教), sometimes translated as 'evil cults' or 'heterodox teachings.'[131] In imperial China, the classification of a religion as xiejiao did not necessarily mean that a religion's teachings were believed to be false or inauthentic, rather, the label was applied to religious groups that were not authorized by the state, or were believed to challenge the legitimacy of the state.[131] In modern China, the term xiejiao continues to be used to denote teachings that the government disapproves of, and these groups face suppression and punishment by authorities. Fourteen different groups in China have been listed by the ministry of public security as xiejiao.[132] Additionally, in 1999, Chinese authorities denounced the Falun Gong spiritual practice as a heretical teaching, and they launched a campaign to eliminate it. According to Amnesty International, the persecution of Falun Gong includes a multifaceted propaganda campaign,[133] a program of enforced ideological conversion and re-education, as well as a variety of extralegal coercive measures, such as arbitrary arrests, forced labour, and physical torture, sometimes resulting in death.[134]

Russia

In 2008 the Russian Interior Ministry prepared a list of "extremist groups." At the top of the list were Islamic groups outside of "traditional Islam," which is supervised by the Russian government. Next listed were "Pagan cults."[135] In 2009 the Russian Ministry of Justice created a council which it named the "Council of Experts Conducting State Religious Studies Expert Analysis." The new council listed 80 large sects which it considered potentially dangerous to Russian society, and it also mentioned that there were thousands of smaller ones. The large sects which were listed included: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Jehovah's Witnesses, and other sects which were loosely referred to as "neo-Pentecostals."[136]

United States

In the 1970s, the scientific status of the "brainwashing theory" became a central topic in U.S. court cases where the theory was used to try to justify the use of the forceful deprogramming of cult members.[13][129] Meanwhile, sociologists critical of these theories assisted advocates of religious freedom in defending the legitimacy of new religious movements in court.[48][130] In the United States the religious activities of cults are protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which prohibits governmental establishment of religion and protects freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly. However, no members of religious groups or cults are granted any special immunity from criminal prosecution.[137] In 1990, the court case of United States v. Fishman (1990) ended the usage of brainwashing theories by expert witnesses such as Margaret Singer and Richard Ofshe.[138] In the case's ruling, the court cited the Frye standard, which states that the scientific theory which is utilized by expert witnesses must be generally accepted in their respective fields. The court deemed brainwashing to be inadmissible in expert testimonies, using supporting documents which were published by the APA Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Methods of Persuasion and Control, literature from previous court cases in which brainwashing theories were used, and expert testimonies which were delivered by scholars such as Dick Anthony.[138][139]

Western Europe

The governments of France and Belgium have taken policy positions which accept "brainwashing" theories uncritically, while the governments of other European nations, such as those of Sweden and Italy, are cautious with regard to brainwashing and as a result, they have responded more neutrally with regard to new religions.[140] Scholars have suggested that the outrage which followed the mass murder/suicides which were perpetuated by the Solar Temple[48][141] have significantly contributed to European anti-cult positions as well as more latent xenophobic and anti-American attitudes which are widespread on the continent.[142] In the 1980s clergymen and officials of the French government expressed concern that some orders and other groups within the Roman Catholic Church would be adversely affected by anti-cult laws which were then being considered.[143]

References

Notes

- Compare the Oxford English Dictionary note for usage in 1875: "cult:…b. A relatively small group of people having (esp. religious) beliefs or practices regarded by others as strange or sinister, or as exercising excessive control over members.… 1875 Brit. Mail 30 Jan. 13/1 Buffaloism is, it would seem, a cult, a creed, a secret community, the members of which are bound together by strange and weird vows, and listen in hidden conclave to mysterious lore." "cult". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- or "sects" in German-speaking countries, the German term sekten having assumed the same derogatory meaning as English "cult."

-

- Austria: Beginning in 2011, the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor's International Religious Freedom Report no longer distinguishes sects in Austria as a separate group. "International Religious Freedom Report for 2012". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Belgium: The Justice Commission of the Belgian House of Representatives published a report on cults in 1997. A Brussels Appeals Court in 2005 condemned the House of Representatives on the grounds that it had damaged the image of an organization listed.

- France: a parliamentary commission of the National Assembly compiled a list of purported cults in 1995. In 2005, the Prime Minister stated that the concerns addressed in the list "had become less pertinent" and that the government needed to balance its concern with cults with respect for public freedoms and laïcité.

- Germany: The legitimacy of a 1997 Berlin Senate report listing cults (sekten) was defended in a court decision of 2003 (Oberverwaltungsgericht Berlin [OVG 5 B 26.00] 25 September 2003). The list is still maintained by Berlin city authorities: Sekten und Psychogruppen – Leitstelle Berlin.

Citations

- Zablocki, Benjamin David; Robbins, Thomas (2001). Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field. University of Toronto Press. p. 473. ISBN 0-8020-8188-6.

- Richardson, James T. 1993. "Definitions of Cult: From Sociological-Technical to Popular-Negative." Review of Religious Research 34(4):348–56. doi:10.2307/3511972. JSTOR 3511972.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin, and Geoffrey William Bromiley. The Encyclopedia of Christianity 4. p. 897. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Stark & Bainbridge 1996, p. 124

- OED, citing American Journal of Sociology 85 (1980). p. 1377: "Cults…like other deviant social movements, tend to recruit people with a grievance, people who suffer from a some variety of deprivation."

- Shaw, Chuck. 2005. "Sects and Cults." Greenville Technical College. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Olson, Paul J. 2006. "The Public Perception of 'Cults' and 'New Religious Movements'." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45 (1): 97–106

- Stark & Bainbridge 1987

- Barker, Eileen. 1999. "New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance." New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response, edited by B. Wilson and J. Cresswell. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20050-4.

- cf. Brink, T. L. 2008. "Unit 13: Social Psychology." Pp. 293–320 in Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. pp 320: "Cult is a somewhat derogatory term for a new religious movement, especially one with unusual theological doctrine or one that is abusive of its membership."

- Bromley, David Melton, and J. Gordon. 2002. Cults, Religion, and Violence. West Nyack, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ingram, Wayne, host. "Turkey Ritual" (transcript). Ep. 2 in Study Religion (podcast). Birmingham: Dept. of Religious Studies, University of Alabama.

- Lewis 2004

- Ryan, Amy. 2000. New Religions and the Anti-Cult Movement: Online Resource Guide in Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 18 November 2005.

- Wilson, Bryan. 2001. "Why the Bruderhof is not a cult." Retrieved 12 July 2017. p. 2. – via Scribd: Wilson makes the same point, saying that the Bruderhof is not a cult, pointing out that the public imagination is captured by five events that have occurred in religious groups: Jonestown, the Branch Davidians, Solar Temple, Aum Shinrikyo, and Heaven's Gate.

- Casino. Bruce J. 15 March 1999. "Defining Religion in American Law" (lecture). Conference On The Controversy Concerning Sects In French-Speaking Europe. Sponsored by CESNUR and CLIMS. Archived from the original on 10 November 2005.

- Clarke, Peter B. 2006. New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World. New York: Routledge.

- Siegler, Elijah. 2007. New Religious Movements. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-183478-9.

- Weber, Max. [1922] 1947. "The Nature of Charismatic Authority and its Routinization." Ch. 4§10 in Theory of Social and Economic Organization, translated by A. R. Anderson and T. Parsons. Available in its original German.

- Swatos, William H. Jr. (1998). "Church-Sect Theory". In William H. Swatos Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. pp. 90–93. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- Campbell, Colin (1998). "Cult". In William H. Swatos Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. pp. 122–23. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- Stark & Bainbridge 1987, p. 25

- Stark & Bainbridge 1987, p. 124

- The Early Unification Church History Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Galen Pumphrey

- Swatos, William H., ed. "Conversion" and "Unification Church" in Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Hartford, CT: AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012 (Conversion) and 13 January 2012 (Unification Church).

- Ashcraft, W. Michael. 2006. African Diaspora Traditions and Other American Innovations, (Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America 5). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98717-6. p. 180.

- Chryssides, George D. [1999] 2001. Exploring New Religions (Issues in Contemporary Religion). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6. p. 1.

- Wallis, Roy. 1975. "Scientology: Therapeutic Cult to Religious Sect." British Sociological Association 9(1):89–100. doi:10.1177/003803857500900105.

- Campbell, Bruce. 1978. "A Typology of Cults." Sociology Analysis. Santa Barbara.

- Oldenburg, Don. [2003] 2003. "Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate." Defence Brief 269. Toronto: Steven Skurka & Associates. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- Dawson 1998, p. 340

- Robbins, Thomas. 1996. In Gods We Trust: New Patterns of Religious Pluralism in America. Transaction Publishers. p. 537. ISBN 978-0-88738-800-2.

- Sipchen, Bob. 17 November 1988. "Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions." Los Angeles Times.

- Stark & Bainbridge 1996

- Gallagher, Eugene V. 2004. The New Religious Movement Experience in America. Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32807-2. p. xv.

- Galanter, Marc, ed. 1989. Cults and New Religious Movements: A Report of the Committee on Psychiatry and Religion of the American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0-89042-212-5.

- Bader, Chris, and A. Demaris. 1996. "A test of the Stark-Bainbridge theory of affiliation with religious cults and sects." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 35:285–303.

- Lewis 2008

- Cowan 2003

- J. Gordon Melton, Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America (New York/London: Garland, 1986; revised edition, Garland, 1992). p. 5

- Martin, Walter Ralston. [1965] 2003. The Kingdom of the Cults (revised ed.), edited by R. Zacharias. US: Bethany House. ISBN 0-7642-2821-8.

- Martin, Walter Ralston. 1978. The Rise of the Cults (revised ed.). Santa Ana: Vision House. pp. 11–12.

- Abanes, Richard. 1997. Defending the Faith: A Beginner's Guide to Cults and New Religions. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House. p. 33.

- House, H. Wayne, and Gordon Carle. 2003. Doctrine Twisting: How Core Biblical Truths are Distorted. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

- Trompf, Garry W. 1987. "Missiology, Methodology and the Study of New Religious Movements." Religious Traditions 10:95–106.

- Enroth, Ronald, ed. 1990. Evangelising the Cults. Milton Keynes, UK: Word Books.

- Geisler, Norman L., and Ron Rhodes. 1997. When Cultists Ask: A Popular Handbook on Cultic Misinterpretations. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

- Richardson & Introvigne 2001

- Shupe, Anson (1998). "Anti-Cult Movement". In William H. Swatos Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- "[C]ertain manipulative and authoritarian groups which allegedly employ mind control and pose a threat to mental health are universally labeled cults. These groups are usually 1) authoritarian in their leadership; 2) communal and totalistic in their organization; 3) aggressive in their proselytizing; 4) systematic in their programs of indoctrination; 5)relatively new and unfamiliar in the United States; 6)middle class in their clientele" (Robbins and Anthony (1982:283), as qtd. in Richardson 1993:351).

- Melton, J. Gordon (10 December 1999). "Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory". CESNUR: Center for Studies on New Religions. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

In the United States at the end of the 1970s, brainwashing emerged as a popular theoretical construct around which to understand what appeared to be a sudden rise of new and unfamiliar religious movements during the previous decade, especially those associated with the hippie street-people phenomenon.

- Bromley, David G. (1998). "Brainwashing". In William H. Swatos Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- Barker, Eileen. 1989. New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Janja, Lalich; Langone, Michael. "Characteristics Associated with Cultic Groups – Revised". International_Cultic_Studies_Association. International Cultic Studies Association. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- O'Reilly, Charles A., and Jennifer A. Chatman. 1996. "Culture as Social Control: Corporations, Cults and Commitment." Research in Organizational Behavior 18:157–200. ISBN 1-55938-938-9. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Wright, Stewart A. 1997. "Media Coverage of Unconventional Religion: Any 'Good News' for Minority Faiths?" Review of Religious Research 39(2):101–15. doi:10.2307/3512176. JSTOR 3512176.

- van Driel, Barend, and J. Richardson. 1988. "Cult versus sect: Categorization of new religions in American print media." Sociological Analysis 49(2):171–83. doi:10.2307/3711011. JSTOR 3711011.

- Hill, Harvey, John Hickman, and Joel McLendon. 2001. "Cults and Sects and Doomsday Groups, Oh My: Media Treatment of Religion on the Eve of the Millennium." Review of Religious Research 43(1):24–38. doi:10.2307/3512241. JSTOR 3512241.

- Barker, Eileen (1986). "Religious Movements: Cult and Anti-Cult Since Jonestown". Annual Review of Sociology. 12: 329–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001553.

- Ayella, Marybeth (1990). "They Must Be Crazy: Some of the Difficulties in Researching 'Cults'". American Behavioral Scientist. 33 (5): 562–77. doi:10.1177/0002764290033005005.

- Cowan, 2003 ix

- Werbner. Pnina. 2003. Pilgrims of Love: The Anthropology of a Global Sufi Cult. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. xvi: "...the excessive use of "cult" is also potentially misleading. With its pejorative connotations"

- Wessinger, Catherine Lowman (2000). How the Millennium Comes Violently. New York/London: Seven Bridges Press. p. 4. ISBN 1-889119-24-5.

- Robinson, B.A. (25 July 2007). "Doomsday, destructive religious cults". Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Turner, Francis J.; Arnold Shanon Bloch, Ron Shor (1 September 1995). "105: From Consultation to Therapy in Group Work With Parents of Cultists". Differential Diagnosis & Treatment in Social Work (4th ed.). Free Press. p. 1146. ISBN 0-02-874007-6.

- Clark, M.D., John Gordon (4 November 1977). "The Effects of Religious Cults on the Health and Welfare of Their Converts". Congressional Record. United States Congress. 123 (181): Extensions of Remarks 37401–03. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Kaslow, Florence Whiteman; Marvin B. Sussman (1982). Cults and the Family. Haworth Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-917724-55-0.

- Zablocki, Benjamin. 31 May 1997. "A Sociological Theory of Cults" (paper). Annual meeting of the American Family Foundation. Philadelphia. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 March 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kranenborg, Reender. 1996. "Sekten... gevaarlijk of niet? [Cults... dangerous or not?]" (in Dutch). Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland 31. Free University Amsterdam. ISSN 0169-7374. ISBN 90-5383-426-5.

- "The impacts of cults on health" (PDF).

- dawson 1998, p. 349

- Seiwert, Hubert. 2003. "Freedom and Control in the Unified Germany: Governmental Approaches to Alternative Religions Since 1989." Sociology of Religion 64(3):367–75, p. 370.

- BVerfG, Order of the First Senate of 26 June 2002, 1 BvR 670/91, paras. 1-102. paras. 57, 60, 62, 91–94; "Zur Informationstätigkeit der Bundesregierung im religiös-weltanschaulichen Bereich" (in German). Press release 68(2002). Federal Constitutional Court Press Office. 30 July 2002. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- Saliba, John A.; J. Gordon Melton, foreword (2003). Understanding New Religious Movements. Rowman Altamira. p. 144. ISBN 0-7591-0356-9.

- Jenkins, Phillip (2000). Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 216, 222. ISBN 0-19-514596-8.

- Stangor, Charles (2004). Social Groups in Action and Interaction. Psychology Press. pp. 42–43: "When Prophecy Fails". ISBN 1-84169-407-X.

- Newman, Dr. David M. (2006). Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life. Pine Forge Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-4129-2814-1.

- Petty, Richard E.; John T. Cacioppo (1996). Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches. Westview Press. p. 139: "Effect of Disconfirming an Important Belief". ISBN 0-8133-3005-X.

- Festinger, Leon; Riecken, Henry W.; Schachter, Stanley (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 1-59147-727-1.

- Jenkins, Philip. 2000. Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History. Oxford University Press. pp. 215–16.

- Pargament, Kenneth I. (1997). The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. Guilford Press. pp. 150–153, 340, section: "Compelling Coping in a Doomsday Cult". ISBN 1-57230-664-5.

- Restall, Matthew, and Amara Solari. 2011. 2012 and the End of the World: the Western Roots of the Maya Apocalypse. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Tourish, Dennis, and Tim Wohlforth. 2000. On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Lalich, Janja. 2003. "'On the Edge' and 'Tabernacle of Hate'" (review). Cultic Studies Review 2(2). Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Tourish, Dennis. 1998. "Ideological Intransigence, Democratic Centralism and Cultism: A Case Study from the Political Left." Cultic Studies Journal 15:33–67.

- Tourish, Dennis. [1998] 2003. "Introduction to ‘Ideological Intransigence, Democratic Centralism and Cultism’." What Next? 27. ISSN 1479-4322.

- Payne, Stanley G. (1996). A History of Fascism, 1914-1945. Routledge. ISBN 0203501322.

- Romania, Country Study Guide. International Business Publications. 1999. p. 52.

- Strenski, Ivan. 1987. Four Theories of Myth in Twentieth-Century History: Cassirer, Eliade, Lévi-Strauss and Malinowski. Macmillan. p. 99.

- Lawrence Winkler, Bellatrix. 2012. Between the Cartwheels. p. 381.

- Rothbard, Murray. 1972. "The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult." Retrieved 6 June 2020. Revised editions: Liberty magazine (1987), and Center for Libertarian Studies (1990).

- Shermer, Michael. 1993. "The Unlikeliest Cult in History." Skeptic 2(2):74–81.

- Shermer, Michael. [1993] 1997. "The Unlikeliest Cult." In Why People Believe Weird Things. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-3090-1.

- Mintz, John. 14 January 1985. "Ideological Odyssey: From Old Left to Far Right." The Washington Post.

- Solomon, Alisa. 26 November 1996. "Commie Fiends of Brooklyn." The Village Voice.

- Lalich, Janja A. 2004. Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24018-6.

- North, David. 1991. Gerry Healy and His Place in the History of the Fourth International. Mehring Books. ISBN 0-929087-58-5.

- Wohlforth, Tim, and Dennis Tourish. 2000. "Gerry Healy: Guru to a Star." Pp. 156–72 in On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Pitt, Bob. 2000. "'Cults, Sects and the Far Left'" (review). What Next? 17. ISSN 1479-4322.

- "Arlette Laguiller n'aime pas le débat". L'Humanité (in French). 11 April 2002. Archived from the original on 29 June 2005.

- Cyril Le Tallec (2006). Les sectes politiques: 1965–1995 (in French). ISBN 9782296003477. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Patrick, Lucy. 1990. Library Journal 115(21):144. Mag.Coll.: 58A2543.

- Bridgstock, Robert. 2014. The Youngest Bishop in England: Beneath the Surface of Mormonism. See Sharp Press. p. 102.

- Cusack, C. 2015. Laws Relating to Sex, Pregnancy, and Infancy: Issues in Criminal Justice. Springer.

- Embry, Jessie L. 1994. "Polygamy." In Utah History Encyclopedia, edited by A. K. Powell. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874804256. OCLC 30473917.

- "The Primer" Archived 11 January 2005 at the Wayback Machine – Helping Victims of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse in Polygamous Communities. A joint report from the offices of the Attorneys General of Arizona and Utah. (2006)

- Dunn, Scott (3 December 2012). "Polygamy, abuse alleged to be hallmarks of cult". Owen Sound Sun Times. Owen Sound, Ontario. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Campbell, Jennifer (17 November 2012). "Allegations of polygamy, abuse and psychological torture within secretive sect". CTVnews.ca. CTV Television Network. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Gowan, Rob (7 April 2014). "Two brothers, alleged Ontario polygamist cult ring leaders, face 31 sex and assault charges". Toronto Sun. Owen Sound, Ont.: Canoe Sun Media. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Patterson, Orlando. 1998. Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two American Centuries. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 1993. The Occult Roots of Nazism. New York: NYU Press.

- Perry, Barbara. 2012. Hate and Bias Crime: A Reader. Routledge. pp. 330–31.

- Piven, Jerry S. (2002). Jihad and Sacred Vengeance: Psychological Undercurrents of History. iUniverse. pp. 104–14. ISBN 0-595-25104-8.

- Goldberg, Carl; Crespo, Virginia (2004). Seeking the Compassionate Life: The Moral Crisis for Psychotherapy and Society. Praeger/Greenwood. p. 161. ISBN 0-275-98196-7.

- Dittmann, Melissa (10 November 2002). "Cults of hatred: Panelists at a convention session on hatred asked APA to form a task force to investigate mind control among destructive cults". Monitor on Psychology. 33 (10). American Psychological Association. p. 30. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Sieghart, Mary Ann (26 October 2001). "The cult figure we could do without". The Times.

- Barron, Maye. 2017. 18JTR 8(1).

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/21/isis-caliphate-islamic-state-raqqa-iraq-islamist

- Rubin, Elizabeth. 13 July 2003. "The Cult of Rajavi." The New York Times Magazine.

- Vick, Karl. 21 June 2003. "Iran Dissident Group Labeled a Terrorist Cult." The Washington Post.

- Boot, Max. 25 October 2006. "How to Handle Iran." Los Angeles Times.

- "No Exit: Human Rights Abuses Inside the Mojahedin Khalq Camps." Human Rights Watch. 2005. Available as etext.

- Banisadr, Masoud (19–20 May 2005). "Cult and extremism / Terrorism". Combating Terrorism and Protecting Democracy: The Role of Civil Society. Centro de Investigación para la Paz. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- Barker, Eileen (2016). Revisionism and Diversification in New Religious Movements. Routledge. pp. 173–74. ISBN 978-1317063612.

- Stern, Steven J., ed. 1998. Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980–1995. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Palmer, David Scott. 1994. Shining Path of Peru (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Gérard Chaliand. "Interview." L'Express (in French)

- Richardson & Introvigne 2001, pp. 143–68

- Davis, Dena S. 1996. "Joining a Cult: Religious Choice or Psychological Aberration." Journal of Law and Health.

- Edelman, Bryan; Richardson, James T. (2003). "Falun Gong and the Law: Development of Legal Social Control in China". Nova Religio. 6 (2): 312–31. doi:10.1525/nr.2003.6.2.312.

- Penny, Benjamin (2012). The Religion of Falun Gong. University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-226-65501-7.

- Center for Religious Freedom. February 2002. "Report Analyzing Seven Secret Chinese Government Documents." Washington: Freedom House.

- Lum, Thomas (25 May 2006). "CRS Report for Congress: China and Falun Gong" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- "China: The crackdown on Falun Gong and other so-called "heretical organizations"". Amnesty International. 23 March 2000. Archived from the original on 11 July 2003. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- Soldatov, Andreĭ, and I. Borogan. 2010. The new nobility : the restoration of Russia's security state and the enduring legacy of the KGB. New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 65–66.

- Marshall, Paul. 2013. Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians. Thomas Nelson Inc.

- Ogloff, J. R.; Pfeifer, J. E. (1992). "Cults and the law: A discussion of the legality of alleged cult activities". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 10 (1): 117–40. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370100111.

- United States v. Fishman, 743 F. Supp. 713 (N.D. Cal. 1990).

- Introvigne, Massimo (2014). "Advocacy, brainwashing theories, and new religious movements". Religion. 44 (2): 303–319. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2014.888021.

- Richardson & Introvigne 2001, pp. 144–46

- Robbins, Thomas (2002). "Combating 'Cults' and 'Brainwashing' in the United States and Europe: A Comment on Richardson and Introvigne's Report". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 40 (2): 169–76. doi:10.1111/0021-8294.00047.

- Beckford, James A. (1998). "'Cult' Controversies in Three European Countries". Journal of Oriental Studies. 8: 174–84.

- Richardson, James T. (2004). Regulating religion: case studies from around the globe. New York: Kluwer Acad. / Plenum Publ. ISBN 0306478862.

Sources

- Cowan, Douglas E. 2003. Bearing False Witness? An Introduction to the Christian Countercult. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97459-6.

- Dawson, Lorne L. 1998. Cults in Context: Readings in the Study of New Religious Movements. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0478-6.

- Lewis, James R. 2004. The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

- Richardson, James T. 1993. "Definitions of Cult: From Sociological-Technical to Popular-Negative." Review of Religious Research 34(4):348–56. doi:10.2307/3511972. JSTOR 3511972.

- Richardson, James T. and Massimo Introvigne. 2001. "'Brainwashing' Theories in European Parliamentary and Administrative Reports on 'Cults' and 'Sects'." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40(2):143–68. doi:10.1111/0021-8294.00046.

- Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. 1987. The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05731-9.

- — 1996. A Theory of Religion. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 0-8135-2330-3.

Further reading

| Look up cult in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cult |

Books

- Barker, E. (1989) New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction, London, HMSO

- Bromley, David et al.: Cults, Religion, and Violence, 2002, ISBN 0-521-66898-0

- Enroth, Ronald. (1992) Churches that Abuse, Zondervan, ISBN 0-310-53290-6 Full text online

- Esquerre, Arnaud: La manipulation mentale. Sociologie des sectes en France, Fayard, Paris, 2009.

- House, Wayne: Charts of Cults, Sects, and Religious Movements, 2000, ISBN 0-310-38551-2

- Kramer, Joel and Alstad, Diane: The Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power, 1993.

- Lalich, Janja: Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults, 2004, ISBN 0-520-24018-9

- Landau Tobias, Madeleine et al. : Captive Hearts, Captive Minds, 1994, ISBN 0-89793-144-0

- Lewis, James R. Odd Gods: New Religions and the Cult Controversy, Prometheus Books, 2001

- Martin, Walter et al.: The Kingdom of the Cults, 2003, ISBN 0-7642-2821-8

- Melton, Gordon: Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America, 1992 ISBN 0-8153-1140-0

- Oakes, Len: Prophetic Charisma: The Psychology of Revolutionary Religious Personalities, 1997, ISBN 0-8156-0398-3

- Singer, Margaret Thaler: Cults in Our Midst: The Continuing Fight Against Their Hidden Menace, 1992, ISBN 0-7879-6741-6

- Tourish, Dennis: 'On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left, 2000, ISBN 0-7656-0639-9

- Zablocki, Benjamin et al.: Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field, 2001, ISBN 0-8020-8188-6

Articles

- Langone, Michael: Cults: Questions and Answers

- Lifton, Robert Jay: Cult Formation, The Harvard Mental Health Letter, February 1991

- Robbins, T. and D. Anthony, 1982. "Deprogramming, brainwashing and the medicalization of deviant religious groups" Social Problems 29 pp. 283–97.

- Rosedale, Herbert et al.: On Using the Term "Cult"

- Van Hoey, Sara: Cults in Court The Los Angeles Lawyer, February 1991

- Zimbardo, Philip: What messages are behind today's cults?, American Psychological Association Monitor, May 1997

- Aronoff, Jodi; Lynn, Steven Jay; Malinosky, Peter. Are cultic environments psychologically harmful?, Clinical Psychology Review, 2000, Vol. 20 No. 1 pp. 91–111