Martyr

A martyr (Greek: μάρτυς, mártys, "witness"; stem μάρτυρ-, mártyr-) is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, refusing to renounce, or refusing to advocate a religious belief or cause as demanded by an external party. In the martyrdom narrative of the remembering community, this refusal to comply with the presented demands results in the punishment or execution of an actor by an alleged oppressor. Accordingly, the status of the 'martyr' can be considered a posthumous title as a reward for those who are considered worthy of the concept of martyrdom by the living, regardless of any attempts by the deceased to control how they will be remembered in advance.[1] Insofar, the martyr is a relational figure of a society's boundary work that is produced by collective memory.[2] Originally applied only to those who suffered for their religious beliefs, the term has come to be used in connection with people killed for a political cause.

Most martyrs are considered holy or are respected by their followers, becoming symbols of exceptional leadership and heroism in the face of difficult circumstances. Martyrs play significant roles in religions. Similarly, martyrs have had notable effects in secular life, including such figures as Socrates, among other political and cultural examples.

Meaning

In its original meaning, the word martyr, meaning witness, was used in the secular sphere as well as in the New Testament of the Bible.[3] The process of bearing witness was not intended to lead to the death of the witness, although it is known from ancient writers (e.g. Josephus) and from the New Testament that witnesses often died for their testimonies.

During the early Christian centuries, the term acquired the extended meaning of believers who are called to witness for their religious belief, and on account of this witness, endure suffering or death. The term, in this later sense, entered the English language as a loanword. The death of a martyr or the value attributed to it is called martyrdom.

The early Christians who first began to use the term martyr in its new sense saw Jesus as the first and greatest martyr, on account of his crucifixion.[4][5][6] The early Christians appear to have seen Jesus as the archetypal martyr.[7]

The word martyr is used in English to describe a wide variety of people. However, the following table presents a general outline of common features present in stereotypical martyrdoms.

| 1. | A hero | A person of some renown who is devoted to a cause believed to be admirable. |

| 2. | Opposition | People who oppose that cause. |

| 3. | Foreseeable risk | The hero foresees action by opponents to harm him or her, because of his or her commitment to the cause. |

| 4. | Courage and Commitment | The hero continues, despite knowing the risk, out of commitment to the cause. |

| 5. | Death | The opponents kill the hero because of his or her commitment to the cause. |

| 6. | Audience response | The hero's death is commemorated. People may label the hero explicitly as a martyr. Other people may in turn be inspired to pursue the same cause. |

Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í Faith, martyrs are those who sacrifice their lives serving humanity in the name of God.[9] However, Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, discouraged the literal meaning of sacrificing one's life. Instead, he explained that martyrdom is devoting oneself to service to humanity.[9]

Chinese culture

Martyrdom was extensively promoted by the Tongmenghui and the Kuomintang party in modern China. Revolutionaries who died fighting against the Qing dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution and throughout the Republic of China period, furthering the cause of the revolution, were recognized as martyrs.

Christianity

In Christianity, a martyr, in accordance with the meaning of the original Greek martys in the New Testament, is one who brings a testimony, usually written or verbal. In particular, the testimony is that of the Christian Gospel, or more generally, the Word of God. A Christian witness is a biblical witness whether or not death follows.[10] However, over time many Christian testimonies were rejected, and the witnesses put to death, and the word martyr developed its present sense.

The concept of Jesus as a martyr has recently received greater attention. Analyses of the Gospel passion narratives have led many scholars to conclude that they are martyrdom accounts in terms of genre and style.[11][12][13] Several scholars have also concluded that Paul the Apostle understood Jesus' death as a martyrdom.[14][15][16][17][18][19] In light of such conclusions, some have argued that the Christians of the first few centuries would have interpreted the crucifixion of Jesus as a martyrdom.[7][20]

In the context of church history, from the time of the persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire, it developed that a martyr was one who was killed for maintaining a religious belief, knowing that this will almost certainly result in imminent death (though without intentionally seeking death). This definition of martyr is not specifically restricted to the Christian faith. Though Christianity recognizes certain Old Testament Jewish figures, like Abel and the Maccabees, as holy, and the New Testament mentions the imprisonment and beheading of John the Baptist, Jesus's possible cousin and his prophet and forerunner, the first Christian witness, after the establishment of the Christian faith (at Pentecost), to be killed for his testimony was Saint Stephen (whose name means "crown"), and those who suffer martyrdom are said to have been "crowned". From the time of Constantine, Christianity was decriminalized, and then, under Theodosius I, became the state religion, which greatly diminished persecution (although not for non-Nicene Christians). As some wondered how then they could most closely follow Christ there was a development of desert spirituality, desert monks, self-mortification, ascetics, (Paul the Hermit, St. Anthony), following Christ by separation from the world. This was a kind of white martyrdom, dying to oneself every day, as opposed to a red martyrdom, the giving of one's life in a violent death.[21]

In Christianity, death in sectarian persecution can be viewed as martyrdom. For example, the Spanish Inquisition began in 1481. There were martyrs recognized on both sides of the schism between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England after 1534. Two hundred and eighty-eight Christians were martyred for their faith by public burning between 1553 and 1558 by the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I in England leading to the reversion to the Church of England under Queen Elizabeth I in 1559. "From hundreds to thousands" of Waldensians were martyred in the Massacre of Mérindol in 1545. Three hundred Roman Catholics were said to be martyred by the Church authorities in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Even more modern day accounts of martyrdom for Christ exist, depicted in books such as Jesus Freaks, though the numbers are disputed. There are claims that the numbers of Christians killed for their faith annually are greatly exaggerated,[22] but the fact of ongoing Christian martyrdoms remains undisputed.[23][24][25][26]

Hinduism

Despite the promotion of ahimsa (non-violence) within Sanatana Dharma, and there being no concept of martyrdom,[27] there is the belief of righteous duty (dharma), where violence is used as a last resort to resolution after all other means have failed. Examples of this are found in the Mahabharata. Upon completion of their exile, the Pandavas were refused the return of their portion of the kingdom by their cousin Duruyodhana; and following which all means of peace talks by Krishna, Vidura and Sanjaya failed. During the great war which commenced, even Arjuna was brought down with doubts, e.g., attachment, sorrow, fear. This is where Krishna instructs Arjuna how to carry out his duty as a righteous warrior and fight.

Islam

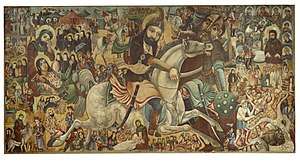

Shahid originates from the Quranic Arabic word meaning "witness" and is also used to denote a martyr. Shahid occurs frequently in the Quran in the generic sense "witness", but only once in the sense "martyr, one who dies for his faith"; this latter sense acquires wider use in the hadiths. Islam views a martyr as a man or woman who dies while conducting jihad, whether on or off the battlefield (see greater jihad and lesser jihad).[28] The concept of the martyr in Islam had been made prominent during the Islamic revolution (1978/79) in Iran and the subsequent Iran-Iraq war, so that the cult of the martyr had a lasting impact on the course of revolution and war.[29]

Judaism

Martyrdom in Judaism is one of the main examples of Kiddush Hashem, meaning "sanctification of God's name" through public dedication to Jewish practice. Religious martyrdom is considered one of the more significant contributions of Hellenistic Judaism to Western Civilization. 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees recount numerous martyrdoms suffered by Jews resisting Hellenizing (adoption of Greek ideas or customs of a Hellenistic civilization) by their Seleucid overlords, being executed for such crimes as observing the Sabbath, circumcising their boys or refusing to eat pork or meat sacrificed to foreign gods. According to W. H. C. Frend, "Judaism was itself a religion of martyrdom" and it was this "Jewish psychology of martyrdom" that inspired Christian martyrdom.

Sikhism

Martyrdom (called shahadat in Punjabi) is a fundamental concept in Sikhism and represents an important institution of the faith. The Sikh Gurus and the Sikhs that followed them are some of the greatest examples of martyrs who fought [30] against Mughal tyranny and oppression, upholding the fundamentals of Sikhism, where their lives were taken during non-violent protesting or in battles. Sikhs believe in Ibaadat se Shahadat (from love to martyrdom). Some famous Sikh martyrs include:[31]

- Guru Arjan, the fifth leader of Sikhism. Guru ji was brutally tortured for almost 5 days before he attained shaheedi, or martyrdom.

- Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth guru of Sikhism, martyred on 11 November 1675. He is also known as Dharam Di Chadar (i.e. "the shield of Religion"), suggesting that to save Hinduism, the guru gave his life.

- Bhai Dayala is one of the Sikhs who was martyred at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 due to his refusal to accept Islam.

- Bhai Mati Das is considered by some one of the greatest martyrs in Sikh history, martyred at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 to save Hindu Brahmins.

- Bhai Sati Das is also considered by some one of the greatest martyrs in Sikh history, martyred along with Guru Teg Bahadur at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 to save kashmiri pandits.

- Sahibzada Ajit Singh, Sahibzada Jujhar Singh, Sahibzada Zorawar Singh and Sahibzada Fateh Singh – the four sons of Guru Gobind Singh, the 10th Sikh guru.[32]

Notable martyrs

- 399 BCE – Socrates, much of what is known about the life of Socrates has been drawn from the writings of Plato, which more often than not focus on the events surrounding the death of Socrates. Plato's writings discuss how the state charges Socrates with corrupting the youth. Socrates reached martyrdom when he chose death over escape, as in so doing he chose to die for what he believed in.[33] This is significant in the extent to which it affected his followers and the legacy of his ideas.

- c. 34 CE – Saint Stephen, considered to be the first Christian martyr.

- c. 2nd century CE – Ten Martyrs of Judaism.

- c. 288 – Saint Sebastian, the subject of many works of art.

- c. 304 – Saint Agnes of Rome, beheaded for refusing to forsake her devotion to Christ, for Roman paganism.

- c. 680 – Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammed.

- 1415 – Jan Hus, Christian reformer burned at the stake for heresy

- 1535 – Thomas More, beheaded for refusing to acknowledge Henry VIII as Supreme Head of the Church of England.

- 1606 – Guru Arjan Dev, the fifth leader of Sikhism.

- 1675 – Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Guru of Sikhism, referred to as "Hind di Chadar" or "Shield of India" martyred in defense of religious freedom of Hindus.

- 1941 – Maximilian Kolbe, OFM, a Roman Catholic priest, who was martyred in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz, August 1941.

Political martyrs

A political martyr is someone who suffers persecution or death for advocating, renouncing, refusing to renounce, or refusing to advocate a political belief or cause. Notable political martyrs include:

- 1793 – Jean-Paul Marat, a French Jacobin assassinated by Charlotte Corday.

- 1793 – Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer executed during the French Revolution for assassinating Jean-Paul Marat.

- 1835 - King Hintsa, a Xhosa monarch who was killed and mutilated by the British fleeing captivity during Frontier wars in what is known as the Hintsa War.

- 1865 – Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States. Assassinated by a Confederate sympathizer after the end of the American Civil War.

- 1919 – Rosa Luxemburg, a German Marxist revolutionary executed along with Karl Liebknecht for their roles in the Spartacist uprising.

- 1929 – Nurkhon Yuldashkhojayeva, an Uzbek dancer murdered in an honor killing for dancing without veil; depicted as a martyr of Hujum in the play "Nurkhon" by Kamil Yashin after her death.

- 1930 – Horst Wessel killed by Albrecht Höhler (a Communist Party member). Became Nazi martyr, due to promotion by Joseph Goebbels.

- 1943 – Hans and Sophie Scholl, killed during the Holocaust for distributing leaflets opposing Nazism.

- 1948 – Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian nationalist leader referred as the 'Father of the Nation' by Indians, assassinated by Hindu fanatic Nathuram Godse for trying to spread communal harmony.

- 1956 – Imre Nagy, a Hungarian communist politician. Executed for his leadership role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

- 1961 – Patrice Lumumba, born in 1925, assassinated in Mwadingusha in Katanga, Prime minister at the time in 61. He is considered the symbol of the independence of Congo.

- 1963 – Medgar Evers, assassinated in 1963 for his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement in his home state Mississippi.

- 1965 – Malcolm X, assassinated in 1965 on account of his leadership in Black nationalism.

- 1966 – Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian Islamist and a key figure in the founding of modern political Islam in the 1950s. Hung in 1966 for plotting the assassination of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

- 1967 – Che Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary. Executed for trying to foment revolution in Bolivia.

- 1968 – Martin Luther King Jr., assassinated in 1968 for his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement.

- 1977 – Steve Biko, a South African activist killed in Police Custody for his anti-Apartheid activism.

- 1978 – Harvey Milk, the first openly gay city council member of a major US city (San Francisco), murdered by fellow city council member Dan White who had previously expressed prejudiced views against homosexuals.

- 1980 – Óscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, murdered after calling on Salvadoran soldiers to disobey commands to kill civilians.

- 1981 – Bobby Sands, an Irish Republican who died during a hunger strike while imprisoned.

- 1987 – Thomas Sankara, a Burkinabé Marxist revolutionary, deposed and assassinated for his efforts to transform the Republic of Upper Volta (which he renamed Burkina Faso) into a socialist state.

- 1989 – Safdar Hashmi, an Indian Marxist revolutionary playwright and actor, killed while performing a street play in support of workers' rights.

- 1993 - Thembisile Chris Hani, South Africa Apartheid Activist, ANC military wing Mkhonto weSizwe commander was assassinated by Janusz Walus outside his home.

- 1995 – Ken Saro-Wiwa, Nigerian activist killed for speaking against the destruction of indigenous Ogoni land.

- 1995 – Iqbal Masih, a Pakistani child killed at age 12 for advocating against child labor.

Revolutionary martyr

The term "revolutionary martyr" usually relates to those dying in revolutionary struggle.[34][35] During the 20th century, the concept was developed in particular in the culture and propaganda of communist or socialist revolutions, although it was and is also used in relation to nationalist revolutions.

- In the culture of North Korea, martyrdom is a consistent theme in the ongoing revolutionary struggle, as depicted in literary works such as Sea of Blood. There is also a Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery in the country.

- In Vietnam, those who died in the independence struggle are often honoured as martyrs, or liệt sĩ in Vietnamese. Nguyễn Thái Học and schoolgirl Võ Thị Sáu are two examples.[36]

- In India, the term "revolutionary martyr" is often used when referring to the world history of socialist struggle. Guru Radha Kishan was a notable Indian independence activist and communist politician known to have used this phrasing.

See also

References

- Gölz, Olmo "Martyrdom and the Struggle for Power. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Martyrdom in the Modern Middle East.", Behemoth 12, no. 1 (2019): 2–13, 5.

- Gölz, Olmo "The Imaginary Field of the Heroic: On the Contention between Heroes, Martyrs, Victims and Villains in Collective Memory." In helden.heroes.héros, Special Issue 5: Analyzing Processes of Heroization. Theories, Methods, Histories. Ed. by N Falkenhayner, S Meurer and T Schlechtriemen (2019): 27–38, 27.

- See e.g. Alison A. Trites, The New Testament Concept of Witness, ISBN 0-521-60934-8 and ISBN 978-0-521-60934-0.

- Frances M. Young, The Use of Sacrificial Ideas in Greek Christian Writers from the New Testament to John Chrysostom (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2004), pp. 107.

- Eusebius wrote of the early Christians: "They were so eager to imitate Christ ... they gladly yielded the title of martyr to Christ, the true Martyr and Firstborn from the dead." Eusebius, Church History 5.1.2.

- Scholars believe that Revelation was written during the period when the word for witness was gaining its meaning of martyr. Revelation describes several Christian reh with the term martyr (Rev 17:6, 12:11, 2:10-13), and describes Jesus in the same way ("Jesus Christ, the faithful witness/martyr" in Rev 1:5, and see also Rev 3:14).

- A. J. Wallace and R. D. Rusk, Moral Transformation: The Original Christian Paradigm of Salvation (New Zealand: Bridgehead, 2011), pp. 217-229.

- From A. J. Wallace and R. D. Rusk, Moral Transformation: The Original Christian Paradigm of Salvation (New Zealand: Bridgehead, 2011), pp. 218.

- Winters, Jonah (1997-09-19). "Conclusion". Dying for God: Martyrdom in the Shi'i and Babi Religions. M.A. Thesis. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- See Davis, R."Martyr, or Witness?" Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, New Matthew Bible Project

- J. W. van Henten, "Jewish Martyrdom and Jesus' Death" in Jörg Frey & Jens Schröter (eds.), Deutungen des Todes Jesu im Neuen Testament (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005) pp. 157 – 168.

- Donald W. Riddle, "The Martyr Motif in the Gospel According to Mark." The Journal of Religion, IV.4 (1924), pp. 397 – 410.

- M. E. Vines, M. E. Vines, "The 'Trial Scene' Chronotype in Mark and the Jewish Novel", in G. van Oyen and T. Shepherd (eds.), The Trial and Death of Jesus: Essays on the Passion Narrative in Mark (Leuven: Peeters, 2006), pp. 189 – 203.

- Stephen Finlan, The Background and Content of Paul's Cultic Atonement Metaphors (Atlanta, GA: SBL, 2004), pp. 193 – 210

- Sam K. Williams, Death as Saving Event: The Background and Origin of a Concept (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press for Harvard Theological Review, 1975), pp. 38 – 41.

- David Seeley, The Noble Death (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1990), pp. 83 – 112.

- Stanley Stowers, A Rereading of Romans: Justice, Jews, and Gentiles (Ann Arbor: Yale University Press, 1997), p. 212f.

- Jarvis J. Williams, Maccabean Martyr Traditions in Paul's Theology of Atonement (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2010)

- S. A. Cummins, Paul and the Crucified Christ in Antioch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- Stephen J. Patterson, Beyond the Passion: Rethinking the Death and Life of Jesus (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2004).

- Arena, Saints, directed by Paul Tickell, 2006

- Alexander, Ruth (2013-11-12). "Are there really 100,000 new Christian martyrs every year?". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- "IS 'beheads Christian hostages' in Nigeria". BBC News. 2019-12-27. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- Chiaramonte, Perry (2016-04-21). "Martyr killed by bulldozer becomes symbol of growing persecution of Christians in China". Fox News. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- "Christian evangelist murdered in southeast Turkey". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- "Christianity's Modern-Day Martyrs: Victims of Radical Islam". ABC News. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- Stephen Knapp (2006) The Power of the Dharma: An Introduction to Hinduism and Vedic Culture

- A. Ezzati (1986). The Concept Of Martyrdom In Islam. Tehran University.

- Gölz, "Martyrdom and Masculinity in Warring Iran. The Karbala Paradigm, the Heroic, and the Personal Dimensions of War.", Behemoth 12, no. 1 (2019): 35–51, 35.

- "The Concept of Martyrdom and Sikhism" (PDF). globalsikhstudies.net.

- Sandeep Singh Bajwa (2000-02-11). "Biographies of Great Sikh Martyrs". Sikh-history.com. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- "Sacrifice and Martyrdom - Gateway to Sikhism". Allaboutsikhs.com. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- Reeve, C.D.C. (2012). A Plato Reader: Eight Essential Dialogues. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company Inc. pp. 47–59. ISBN 978-1-60384-811-4.

- The French Revolution Page 95 Linda Frey, Marsha Frey - 2004 "He was immortalized by the painter David in the famous painting of the death scene that became the icon of the revolution and an emblem of revolutionary propaganda. The revolutionary martyr was commemorated not only in painting and in ..."

- Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican ... - Page 250 John Mason Hart - 1987 "They popularized Ricardo Flores Magon as a revolutionary martyr who was harassed by the American and Mexican ..."

- Vietnam At War Mark Philip Bradley - 2009 "As the concept of 'sacrifice' (hi sinh) came to embody the state's narrative of sacred war (chien tranh than thanh), the ultimate sacrifice was considered to be death in battle as a 'revolutionary martyr' (liet si)."

Bibliography

- "Martyrs", Catholic Encyclopedia

- Foster, Claude R. Jr. (1995). Paul Schneider, the Buchenwald apostle: a Christian martyr in Nazi Germany: A Sourcebook on the German Church Struggle. Westchester, PA: SSI Bookstore, West Chester University. ISBN 978-1-887732-01-7

Further reading

- Bélanger, Jocelyn J., et al. "The Psychology of Martyrdom: Making the Ultimate Sacrifice in the Name of a Cause." Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 107.3 (2014): 494-515. Print.

- Kateb, George. "Morality and Self-Sacrifice, Martyrdom and Self-Denial." Social Research 75.2 (2008): 353-94. Print.

- Olivola, Christopher Y. and Eldar Shafir. "The Martyrdom Effect: When Pain and Effort Increase Prosocial Contributions." Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26, no. 1 (2013): 91-105.

- PBS. "Plato and the Legacy of Socrates." PBS. https://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/background/41a.html (accessed October 21, 2014).

- Reeve, C. D. C.. A Plato Reader: Eight Essential Dialogues. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 2012. Print.

External links

| Look up martyr in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Martyrdom |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martyrs. |

- Fox's Book of Martyrs – 16th century classic book, accounts of martyrdoms

- "Martyrdom from the perspective of sociology". Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion.