Easington Colliery

Easington Colliery is a town in County Durham, England, known for a history of coal mining. It is situated to the north of Horden, and a short distance to the east of Easington Village. The town suffered a significant mining accident on 29 May 1951, when an explosion in the mine resulted in the deaths of 83 men (including 2 rescue workers).

| Easington Colliery | |

|---|---|

Byron Street | |

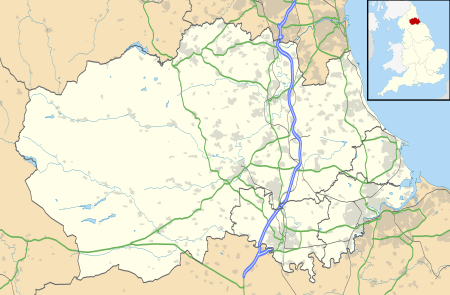

Easington Colliery Location within County Durham | |

| Population | 5,022 |

| OS grid reference | NZ432437 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Peterlee |

| Postcode district | SR8 |

| Police | Durham |

| Fire | County Durham and Darlington |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

Easington had a population of 4,959 in 2001,[1] and 5,022 at the 2011 Census.[2]

History

Easington Colliery began when the pit was sunk in 1899, near the coast; indeed the pylon for the aerial flight that carried tubs of colliery waste from the mine stood just inside the North Sea.[3] Thousands of workers came to the area from all parts of Britain and with the new community came new shops, pubs, clubs, and many rows of terraced "colliery houses" for the mine workers and their families.

On 7 May 1993, the mine was closed, with the loss of 1,400 jobs, causing a decline in the local economy. The pit shaft headgear was demolished the following year.

The town's former infant and junior schools were built in 1911. They are adjacent to Seaside Line but lie derelict. A development company bought the buildings in 2003 and applied for planning permission to build 39 residential units, but a public inquiry gave a ruling that protected the buildings from demolition. They have since been listed.[4]

It was decided in 2009 to create a new unitary authority — Durham County Council — to cover the whole of the county, and most of Easington's staff moved into new offices in Seaham.[5] Easington District Council's office building, which had been the department's home for over eighty years, was demolished in April 2013. The fixtures and fittings, including oak desks, from the council chamber were placed in storage at Beamish Museum.

Victoria Cross

The youngest soldier to be awarded a Victoria Cross during World War II was Dennis Donnini from Easington. His father, an Italian named Alfred Donnini, had married an Englishwoman named Catherine Brown, and ran an ice cream shop in Easington. Dennis was born on 17 November 1925. He attended Corby Grammar School, Sunderland (later known as St Aidan's Catholic Academy).[6]

In an action on 18 January 1945, Fusilier Donnini (then aged 19) was wounded twice yet still led an assault on the enemy before being killed. His gallantry had enabled his comrades to overcome twice their own number of the enemy. He is buried at the Commonwealth Cemetery in Sittard, The Netherlands.[6]

1951 Colliery explosion

Although the shafts for the colliery had started to be sunk in 1899, the first coals were not drawn until 1910 due to passing through water-bearing strata. Two main pits were sunk: the North Shaft (downcast)[lower-alpha 1] and the South Shaft (upcast).[lower-alpha 2] Both of these reached down to the Hutton seam, at 1,430 feet (440 m) and 1,500 feet (460 m) respectively.[7] The seams worked were Five Quarter, Seven Quarter, Main Coal, Low Main and the Hutton at the bottom.[8] Underground the colliery was split into a number of distinct areas or districts. The explosion occurred in the West or "Duckbill" district (named after the duckbill excavators used in the district), which lies to the northwest of the shafts and to the north of the village. The village is built over the seams, and to safeguard it from subsidence there is a reserved area under it.

Significantly, one district extends for four miles under the North Sea; ventilation was therefore not simple: enough air was needed to ventilate the extremities of the eastern workings, whilst that for the closer faces did not need such a powerful supply. Too much air in the closer workings would starve the distant ones. Supplementary fans and traps needed to be employed.[9] The Duckbill district was being developed and it appears that the effect of this on the ventilation was overlooked, as admitted by the Assistant Agent (Mr H E Morgan) in cross-examination.[10]

The colliery in 1951

From the pit bottoms the main roadways extended 380 yards (350 m) to the north, where the West Level branched off and ran for 640 yards (590 m) west to the junction with the Straight North Headings, which head north via drifts into the Five Quarter seam. The West Level continued into a training area. Around 300 yards (270 m) along the Straight North Headings was a further junction where the First West Roads headed west. Some distance further on the second and third roads branched off.

Along the First West roads were a number of headings both north and south. The seat of the explosion was at the far end, down the 3rd south heading.[8][11]

At the end of the 3rd south heading a cross passage was driven and "long wall" excavation commenced on the retreating wall principle. The cutting machine travels from one end of the long wall to the other, and then back. The cuts are made towards the roads, thus the face retreats from the where it started back towards the start of the headings. Behind the cut is a void (known as "goaf") into which spoil was placed and normally the roof is allowed to collapse upon this spoil as props are withdrawn. In the case of the 3rd south workings this collapse did not occur properly and a void developed above the spoil.[12]

Firedamp and coal dust

The area above the goaf was inadequately ventilated and acted as a reservoir for firedamp. The origin of the firedamp is debatable: either the fractured roof allowed a sudden outburst from the seams above, or else the firedamp was gradually emitted from the waste into the void. Roberts discusses these possibilities in the report and comes down in favour of the latter.[13]

All collieries are susceptible to the build up of coal dust, not just at the face but along the roadways and conveyors. Coal dust when dispersed in air forms an explosive mixture. Mines therefore adopt three principal means of combating this risk: removal of the dust, spraying with water and diluting the coal dust with stone dust. All three were practised at Easington, but not in a satisfactory manner.[14]

Firedamp detection

Firedamp detection was by means of a flame safety lamp. Flame safety lamps need to be monitored to be effective, and in consequence the regulations [lower-alpha 3] require certain men to have lamps with them. The men are not permitted to also have electric lamps with them, to ensure that they are aware of changes in the flame. However written permission from the mine manager may be obtained to allow electric lamps, and this was routinely given.[15] Since the lamps were not needed for illumination, they become just an additional burden to carry and were sometimes left behind. When the explosion occurred both safety lamps had been left behind at the intake and so were not at the face. Roberts is unsure whether the lamps would have detected the firedamp in time.[15]

Explosion

The coal cutter consists of a rotating part with a number of teeth or picks. When these picks hit a pocket of hard rock such as pyrites or quartz they can generate a finely divided powder which is heated by friction. Blunt picks are more likely to produce this grinding and heating than sharp ones. Sparking from the cutters in the Duckbill district had been observed before, but as nothing had followed from the sparking it was ignored.[16]

At Easington in 1951 blunt picks hit a patch of pyrites and generated sparks. This time the firedamp leaking from the void above the goaf was ignited. The resulting explosion travelled down the south headings to the west roads. Such an explosion in a confined space causes a blast of air which can raise up any dust lying around. Here coal dust was raised and the resulting coal dust explosion now travelled along the west roads, down the straight north headings and into the main coal where it reached as far as the training area.[17] Two falls occurred: one in the main coal shortly before the drifts leading to the straight north roads, the other in the Duckbill district shortly before the 3rd south heading.

Men

At that time Durham mines worked three production shifts and a maintenance shift. The fore-shift was from 03:30 to 11:07, the back-shift from 09:45 to 17:22 and night-shift from 16:00 to 23:37. The maintenance and repair shift was the stone-shift from 22:00 to 05:37. Shift timings related to going underground through to returning to the shaft top, therefore at 04:35 both the stone-shift and the fore-shift were underground at the faces.[7] 38 men from the stone-shift and 43 from the fore-shift were killed, all but one instantly. The man who survived died of his injuries just a few hours later. As a result of the total loss of life in the vicinity there were no eye-witness accounts of the explosion or its immediate aftermath.[18]

At the time of the explosion Frank Leadbitter was just outside the shaft-bottom stables and led some men through the dust cloud towards the disaster.[lower-alpha 4] He was joined by William Cook (a fore-overman) who telephoned the colliery manager and arranged for the evacuation of the men. Cook and D. Smith (a head wagon-way man) went along the main coal west haulage road to try to get to the duckbill district. The men continued even after hearing and feeling what they believed was another explosion; a fact marked out for special praise by the Chief Inspector of Mines.[19]

The air in the pit was foul with afterdamp. As the rescuers started to move into the affected area, the canaries carried were overcome almost at once.[19] The afterdamp led to the deaths of a further two men, bringing the total deaths to 83. John Young Wallace (26) was part of a group travelling along the west materials road when he sat down, fell unconscious and died. All the group were using self-contained breathing apparatus with nose clips and mouthpieces. Wallace's set was tested and found to be satisfactory. Post mortem examination revealed emphysema and it was thought that breathlessness caused him to open his mouth and allow atmospheric air to leak in. The air at that point was thought to contain about 3% carbon monoxide.[lower-alpha 5][20] Three days later another rescuer, H Burdess, collapsed in a similar way and died. The post-mortem revealed bullus emphysema. One bulla (blister) on the left lung had ruptured, leading to pain, a partial collapse of the lung and consequent difficulty breathing. The symptoms were though to have led to the man gasping for breath and thereby drawing in a lethal dose of carbon monoxide.[21]

Memorial

A memorial comprising a large carved triangular rock painted white. It bears a tablet of stone removed from the scene of the disaster, and a metal plaque with an inscription. The memorial was inaugurated on 22 March 1952. On the same occasion, Easington Colliery's youngest miner, a boy of 16, planted the first of 83 trees, to line the walkway. Each tree symbolises a life lost in the disaster.

Easington Colliery Brass Band

Easington Colliery Band was founded in 1915. Players with band experience were encouraged by the management to come from the West of Durham to work at the colliery and play in the band. The band was supported financially and run by the joint board of unions, until the start of World War II. The band played for community activities, such as dances, concerts, and competitions. For the duration of the war the Easington Colliery Youth Band became the National Fire Service Band, which was eventually 'demobbed' in 1945 to become the Easington Public Band.

In 1956 the Public Band and the Colliery Band amalgamated to become the Easington Colliery Band as it is today. April 1993 witnessed the end of an era when Easington Colliery finally closed. The band is now self-supporting and relies on funding from concerts held throughout the year. The band is still based in Easington Colliery in the old colliery pay office opposite the Memorial Gardens, which is on the site of the old colliery. The building is the last remaining evidence of the pit.

In popular culture

Easington Colliery doubled as the fictitious Everington in the 2000 film Billy Elliot. About 400 locals were used as extras.[22] Billy Elliot the Musical (2005) is set in Easington and the town is named in song lyrics.

Singer-songwriter Jez Lowe was born and brought up in Easington. His song, "Last of the Widows", was written in 1991 to mark the fortieth anniversary of the pit disaster. Many of his other songs are inspired by life in County Durham and Easington in particular.

Poet, Songwriter and Durham miner Jock Purdon penned and sang the lament "Easington Explosion" regarding the 1951 disaster.

In 1971, members of rock band The Who shot the cover photograph for their album Who's Next at a concrete piling protruding from a spoil tip in the area. This cover was named by the VH1 network as one of the Greatest Album Covers.[23]

In 2008, the town was featured in an episode of Channel 4's The Secret Millionaire,[24] where advertising mogul Carl Hopkins donated over £30,000 to the community.

Peter Lee Hammond was an ex-miner at Easington pit and a singer-songwriter. Every year Easington held a carnival and in 1989 Peter was asked by the Easington Carnival Committee to write and sing a song about the community, mining history and the pit disaster of 1951. The (A) side song was called 'Living in a Mining town' which included Peter singing with his band 'Just Us', and the (B) side was an instrumental version of the song and included Thornley & Wheatley Hill Colliery Brass Bands and local school children from Easington Junior school & Shotton Primary school singing harmony. The (B) side was conducted and brass arrangement by Gorden Kitto. Local renowned poet and Colliery resident Mary Bell also helped organise the singles release. The song became a big hit with the locals and it was decided to make it into a single with the proceeds going to a handicapped school in Easington. As the newspapers and radio got involved then quite a few celebrities gave their support and got involved in giving donations and funding the song, including HRH Prince Charles. The then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Neil Kinnock M.P. and Sir Paul McCartney, and the song was mixed at Abbey Road recording studios. Peter was quoted as saying in a radio interview

"Having one of my songs done at Abbey Road Studios was great What a fantastic place it is and Paul & Lynda helping was a dream, and to have the local school kids and brass bands on the B side shows how strong the mining community is in this area and it gave the community a sense of pride when the single came out, I was very proud & honoured to have been asked to do this for the place where I was born and raised."

A copy of the song was requested by Her Majesty the Queen to be sent to her at Buckingham Palace and a copy of the song was made part of the living history memorabilia exhibition at the Yardy Gallery museum in Sunderland Tyne & Wear. The song was played on many radio stations and was a major success in the area. Peter went on to win many awards for his other songs & recording albums abroad and is still writing to this day.

Gallery

Avon Street

Avon Street Tower Street, which was one of the streets featured in Billy Elliot

Tower Street, which was one of the streets featured in Billy Elliot Bridge under the Durham Coastal Railway

Bridge under the Durham Coastal Railway Seaside Lane, the main shopping area in Easington Colliery

Seaside Lane, the main shopping area in Easington Colliery Memorial Avenue, where, following the mining disaster in 1951, 83 trees were planted, one for each man who was killed.

Memorial Avenue, where, following the mining disaster in 1951, 83 trees were planted, one for each man who was killed.

References

Footnotes

- A downcast shaft is one where air passes down the shaft. At this date ventilation was by induced (sucked through) rather than forced (blown through). The downcast pit was therefore used for the conveyance of men and materials.

- The upcast pit carries air up. Early practice was to use a furnace below ground to induce a draft throughout the mine.

- Coal Mines General Regulations (Firedamp Detectors), 1939

- The report consistently uses the terms inbye meaning towards the faces, away from the shafts and outbye meaning away from the coal and towards the pit bottom.

- 30,000 ppm. Compare to undiluted car exhaust at 7,000 ppm. A fatal concentration is around 667 ppm

Citations

- Office for National Statistics 2004.

- "Parish population 2011". Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "1953 Aerial Flight" - Easington Colliery Memory Book

- The Northern Echo 2012.

- Sunderland Echo 2013.

- ECCI.

- Roberts 1952, p. 4.

- Roberts 1952, p. 5.

- Roberts 1952, p. 7.

- Roberts 1952, p. 30.

- Roberts 1952, Plans.

- Roberts 1952, pp. 16 & 26.

- Roberts 1952, p. 17.

- Roberts 1952, pp. 33-34.

- Roberts 1952, p. 32.

- Roberts 1952, pp. 30-31.

- Roberts 1952, p. 19.

- Roberts 1952, p. 8.

- Roberts 1952, p. 9.

- Roberts 1952, p. 39.

- Roberts 1952, p. 40.

- "Feature: Billy Elliot". BBC Tyne. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- VH1.com.

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/wear/content/articles/2008/08/26/secret_millionaire_feature.shtml

Bibliography

- "History". Easington Colliery Club & Institute Ltd. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- The Northern Echo (16 April 2012). "Firefighters tackle fire at derelict Easington Primary School". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 2 May 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office for National Statistics (28 April 2004). "Census 2001 : Parish Headcounts : Easington". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, H C W (September 1952), Report on the causes of, and circumstances attending, the explosion which occurred at Easington Colliery, County Durham, on the 29th May, 1951., Cmd 8646, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, hdl:1842/5365

- Sunderland Echo (26 April 2013). "Bulldozers move in on historic offices". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 15 June 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Greatest Album Covers". VH1.com. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Easington Colliery. |