Collage

Collage (/kəˈlɑːʒ/, from the French: coller, "to glue" or "to stick together";[1]) is a technique of art creation, primarily used in the visual arts, but in music too, by which art results from an assemblage of different forms, thus creating a new whole. (Compare with pastiche, which is a "pasting" together.)

A collage may sometimes include magazine and newspaper clippings, ribbons, paint, bits of colored or handmade papers, portions of other artwork or texts, photographs and other found objects, glued to a piece of paper or canvas. The origins of collage can be traced back hundreds of years, but this technique made a dramatic reappearance in the early 20th century as an art form of novelty.

The term Papier collé was coined by both Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in the beginning of the 20th century when collage became a distinctive part of modern art.[2]

History

Early precedents

Techniques of collage were first used at the time of the invention of paper in China, around 200 BC. The use of collage, however, wasn't used by many people until the 10th century in Japan, when calligraphers began to apply glued paper, using texts on surfaces, when writing their poems.[3] The technique of collage appeared in medieval Europe during the 13th century. Gold leaf panels started to be applied in Gothic cathedrals around the 15th and 16th centuries. Gemstones and other precious metals were applied to religious images, icons, and also, to coats of arms.[3] An 18th-century example of collage art can be found in the work of Mary Delany. In the 19th century, collage methods also were used among hobbyists for memorabilia (e.g. applied to photo albums) and books (e.g. Hans Christian Andersen, Carl Spitzweg).[3] Many institutions have attributed the beginnings of the practice of collage to Picasso and Braque in 1912, however, early Victorian photocollage suggest collage techniques were practiced in the early 1860s.[4] Many institutions recognize these works as memorabilia for hobbyists, though they functioned as a facilitator of Victorian aristocratic collective portraiture, proof of female erudition, and presented a new mode of artistic representation that questioned the way in which photography is truthful. In 2009, curator Elizabeth Siegel organized the exhibition: Playing with Pictures [5] at the Art Institute Chicago to acknowledge collage works by Alexandra of Denmark and Mary Georgina Filmer among others. The exhibition later traveled to The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Art Gallery of Ontario.

Collage and modernism

Despite the pre-twentieth-century use of collage-like application techniques, some art authorities argue that collage, properly speaking, did not emerge until after 1900, in conjunction with the early stages of modernism.

For example, the Tate Gallery's online art glossary states that collage "was first used as an artists' technique in the twentieth century.".[6] According to the Guggenheim Museum's online art glossary, collage is an artistic concept associated with the beginnings of modernism, and entails much more than the idea of gluing something onto something else. The glued-on patches which Braque and Picasso added to their canvases offered a new perspective on painting when the patches "collided with the surface plane of the painting."[7] In this perspective, collage was part of a methodical reexamination of the relation between painting and sculpture, and these new works "gave each medium some of the characteristics of the other," according to the Guggenheim essay. Furthermore, these chopped-up bits of newspaper introduced fragments of externally referenced meaning into the collision: "References to current events, such as the war in the Balkans, and to popular culture enriched the content of their art." This juxtaposition of signifiers, "at once serious and tongue-in-cheek," was fundamental to the inspiration behind collage: "Emphasizing concept and process over end product, collage has brought the incongruous into meaningful congress with the ordinary."[7]

Collage in painting

%2C_cut_and_pasted_colored_paper%2C_gouache_and_charcoal_on_paperboard%2C_43.5_x_33_cm%2C_Scottish_National_Gallery_of_Modern_Art%2C_Edinburgh.jpg)

Collage in the modernist sense began with Cubist painters Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. According to some sources, Picasso was the first to use the collage technique in oil paintings. According to the Guggenheim Museum's online article about collage, Braque took up the concept of collage itself before Picasso, applying it to charcoal drawings. Picasso adopted collage immediately after (and could be the first to use collage in paintings, as opposed to drawings):

"It was Braque who purchased a roll of simulated oak-grain wallpaper and began cutting out pieces of the paper and attaching them to his charcoal drawings. Picasso immediately began to make his own experiments in the new medium."[7]

In 1912 for his Still Life with Chair Caning (Nature-morte à la chaise cannée),[8] Picasso pasted a patch of oilcloth with a chair-cane design onto the canvas of the piece.

Surrealist artists have made extensive use of collage. Cubomania is a collage made by cutting an image into squares which are then reassembled automatically or at random. Collages produced using a similar, or perhaps identical, method are called etrécissements by Marcel Mariën from a method first explored by Mariën. Surrealist games such as parallel collage use collective techniques of collage making.

The Sidney Janis Gallery held an early Pop Art exhibit called the New Realist Exhibition in November 1962, which included works by the American artists Tom Wesselmann, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, George Segal, and Andy Warhol; and Europeans such as Arman, Baj, Christo, Yves Klein, Festa, Rotella, Jean Tinguely, and Schifano. It followed the Nouveau Réalisme exhibition at the Galerie Rive Droite in Paris, and marked the international debut of the artists who soon gave rise to what came to be called Pop Art in Britain and The United States and Nouveau Réalisme on the European continent. Many of these artists used collage techniques in their work. Wesselmann took part in the New Realist show with some reservations,[9] exhibiting two 1962 works: Still life #17 and Still life #22.

Another technique is that of canvas collage, which is the application, typically with glue, of separately painted canvas patches to the surface of a painting's main canvas. Well known for use of this technique is British artist John Walker in his paintings of the late 1970s, but canvas collage was already an integral part of the mixed media works of such American artists as Conrad Marca-Relli and Jane Frank by the early 1960s. The intensely self-critical Lee Krasner also frequently destroyed her own paintings by cutting them into pieces, only to create new works of art by reassembling the pieces into collages.

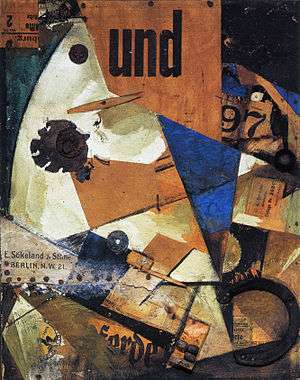

Collage with wood

The wood collage is a type that emerged somewhat later than paper collage. Kurt Schwitters began experimenting with wood collages in the 1920s after already having given up painting for paper collages.[10] The principle of wood collage is clearly established at least as early as his 'Merz Picture with Candle', dating from the mid to late 1920s.

In a sense, wood collage made its debut indirectly at the same time as paper collage, since according to the Guggenheim online, Georges Braque initiated use of paper collage by cutting out pieces of simulated oak-grain wallpaper and attaching them to his own charcoal drawings.[7] Thus, the idea of gluing wood to a picture was implicit from the start, since the paper used was a commercial product manufactured to look like wood.

It was during a fifteen-year period of intense experimentation beginning in the mid-1940s that Louise Nevelson evolved her sculptural wood collages, assembled from found scraps, including parts of furniture, pieces of wooden crates or barrels, and architectural remnants like stair railings or moldings. Generally rectangular, very large, and painted black, they resemble gigantic paintings. Concerning Nevelson's Sky Cathedral (1958), the Museum of Modern Art catalogue states, "As a rectangular plane to be viewed from the front, Sky Cathedral has the pictorial quality of a painting..."[11][12] Yet such pieces also present themselves as massive walls or monoliths, which can sometimes be viewed from either side, or even looked through.

Much wood collage art is considerably smaller in scale, framed and hung as a painting would be. It usually features pieces of wood, wood shavings, or scraps, assembled on a canvas (if there is painting involved), or on a wooden board. Such framed, picture-like, wood-relief collages offer the artist an opportunity to explore the qualities of depth, natural color, and textural variety inherent in the material, while drawing on and taking advantage of the language, conventions, and historical resonances that arise from the tradition of creating pictures to hang on walls. The technique of wood collage is also sometimes combined with painting and other media in a single work of art.

Frequently, what is called "wood collage art" uses only natural wood - such as driftwood, or parts of found and unaltered logs, branches, sticks, or bark. This raises the question of whether such artwork is collage (in the original sense) at all (see Collage and modernism). This is because the early, paper collages were generally made from bits of text or pictures - things originally made by people, and functioning or signifying in some cultural context. The collage brings these still-recognizable "signifiers" (or fragments of signifiers) together, in a kind of semiotic collision. A truncated wooden chair or staircase newel used in a Nevelson work can also be considered a potential element of collage in the same sense: it had some original, culturally determined context. Unaltered, natural wood, such as one might find on a forest floor, arguably has no such context; therefore, the characteristic contextual disruptions associated with the collage idea, as it originated with Braque and Picasso, cannot really take place. (Driftwood is of course sometimes ambiguous: while a piece of driftwood may once have been a piece of worked wood - for example, part of a ship - it may be so weathered by salt and sea that its past functional identity is nearly or completely obscured.)

Decoupage

Decoupage is a type of collage usually defined as a craft. It is the process of placing a picture into an object for decoration. Decoupage can involve adding multiple copies of the same image, cut and layered to add apparent depth. The picture is often coated with varnish or some other sealant for protection.

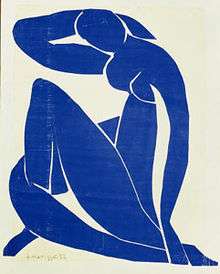

In the early part of the 20th century, decoupage, like many other art methods, began experimenting with a less realistic and more abstract style. 20th-century artists who produced decoupage works include Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. The most famous decoupage work is Matisse's Blue Nude II.

There are many varieties on the traditional technique involving purpose made 'glue' requiring fewer layers (often 5 or 20, depending on the amount of paper involved). Cutouts are also applied under glass or raised to give a three-dimensional appearance according to the desire of the decouper. Currently decoupage is a popular handicraft.

The craft became known as découpage in France (from the verb découper, 'to cut out') as it attained great popularity during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many advanced techniques were developed during this time, and items could take up to a year to complete due to the many coats and sandings applied. Some famous or aristocratic practitioners included Marie Antoinette, Madame de Pompadour, and Beau Brummell. In fact the majority of decoupage enthusiasts attribute the beginning of decoupage to 17th century Venice. However it was known before this time in Asia.

The most likely origin of decoupage is thought to be East Siberian funerary art. Nomadic tribes would use cut out felts to decorate the tombs of their deceased. From Siberia, the practice came to China, and by the 12th century, cut out paper was being used to decorate lanterns, windows, boxes and other objects. In the 17th century, Italy, especially in Venice, was at the forefront of trade with the Far East and it is generally thought that it is through these trade links that the cut out paper decorations made their way into Europe.

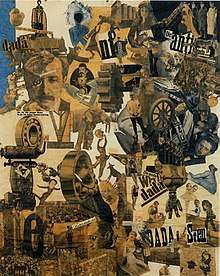

Photomontage

Collage made from photographs, or parts of photographs, is called photomontage. Photomontage is the process (and result) of making a composite photograph by cutting and joining a number of other photographs. The composite picture was sometimes photographed so that the final image is converted back into a seamless photographic print. The same method is accomplished today using image-editing software. The technique is referred to by professionals as compositing.

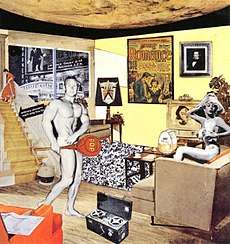

Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? was created in 1956 for the catalogue of the This Is Tomorrow exhibition in London, England in which it was reproduced in black and white. In addition, the piece was used in posters for the exhibit.[13] Richard Hamilton has subsequently created several works in which he reworked the subject and composition of the pop art collage, including a 1992 version featuring a female bodybuilder. Many artists have created derivative works of Hamilton's collage. P. C. Helm made a year 2000 interpretation.[14]

Other methods for combining pictures are also called photomontage, such as Victorian "combination printing", the printing from more than one negative on a single piece of printing paper (e.g. O. G. Rejlander, 1857), front-projection and computer montage techniques. Much as a collage is composed of multiple facets, artists also combine montage techniques. Romare Bearden’s (1912–1988) series of black and white "photomontage projections" is an example. His method began with compositions of paper, paint, and photographs put on boards 8½ × 11 inches. Bearden fixed the imagery with an emulsion that he then applied with handroller. Subsequently, he enlarged the collages photographically.

The 19th century tradition of physically joining multiple images into a composite and photographing the results prevailed in press photography and offset lithography until the widespread use of digital image editing. Contemporary photo editors in magazines now create "paste-ups" digitally.

Creating a photomontage has, for the most part, become easier with the advent of computer software such as Adobe Photoshop, Pixel image editor, and GIMP. These programs make the changes digitally, allowing for faster workflow and more precise results. They also mitigate mistakes by allowing the artist to "undo" errors. Yet some artists are pushing the boundaries of digital image editing to create extremely time-intensive compositions that rival the demands of the traditional arts. The current trend is to create pictures that combine painting, theatre, illustration and graphics in a seamless photographic whole.

Digital collage

Digital collage is the technique of using computer tools in collage creation to encourage chance associations of disparate visual elements and the subsequent transformation of the visual results through the use of electronic media. It is commonly used in the creation of digital art using programs such as Photoshop.

Three-dimensional collage

A 3D collage is the art of putting altogether three-dimensional objects such as rocks, beads, buttons, coins, or even soil to form a new whole or a new object. Examples can include houses, bead circles, etc.

Mosaic

It is the art of putting together or assembling of small pieces of paper, tiles, marble, stones, etc. They are often found in cathedrals, churches, temples as a spiritual significance of interior design. Small pieces, normally roughly quadratic, of stone or glass of different colors, known as tesserae, (diminutive tessellae), are used to create a pattern or picture.

eCollage

The term "eCollage" (electronic Collage) can be used for a collage created by using computer tools.

Collage artists

- Johannes Baader

- Johannes Theodor Baargeld

- Jeannie Baker

- Nick Bantock

- Hannelore Baron

- Romare Bearden

- Peter Blake

- Guy Bleus

- Umberto Boccioni

- Rita Boley Bolaffio

- Henry Botkin

- Pauline Boty

- Mark Bradford

- Georges Braque

- Alberto Burri

- Claude Cahun

- Reginald Case

- Peter Clarke

- Jess Collins

- Greg Colson

- Felipe Jesus Consalvos

- Joseph Cornell

- Amadeo de Souza Cardoso

- Eric Carle

- Jim Dine

- Burhan Doğançay

- Magie Dominic

- Arthur G. Dove

- Jean Dubuffet

- Marcel Duchamp

- Lois Ehlert

- Max Ernst

- Nick Gentry

- Terry Gilliam

- Juan Gris

- Olena Golub.

- George Grosz

- Raymond Hains

- Kenneth Halliwell

- Richard Hamilton

- Raoul Hausmann

- Damien Hirst

- Hannah Höch

- David Hockney

- Istvan Horkay

- Ray Johnson

- Peter Kennard

- Jiří Kolář

- Lee Krasner

- Barbara Kruger

- François Lanzi

- John K. Lawson

- Kazimir Malevich

- Conrad Marca-Relli

- Eugene J. Martin

- Henri Matisse

- John McHale

- Robert Motherwell

- Vik Muniz

- Wangechi Mutu

- Joseph Nechvatal

- Louise Nevelson

- Robert Nickle

- Eduardo Paolozzi

- Sergei Parajanov

- Claude Pélieu

- Francis Picabia

- Pablo Picasso

- Carl Plate

- David Plunkert

- Guillem Ramos-Poquí

- David Ratcliff

- Robert Rauschenberg

- Man Ray

- Gordon Rice

- Larry Rivers

- James Rosenquist

- Martha Rosler

- Mimmo Rotella

- Anne Ryan

- Kurt Schwitters

- Winston Smith

- Gino Severini

- John Stezaker

- Daniel Spoerri

- Francois Szalay - Colos

- Roderick Slater

- Nancy Spero

- Linder Sterling

- Sergei Sviatchenko

- Ivan Tabakovic

- Jonathan Talbot

- Lenore Tawney

- Cecil Touchon

- Scott Treleaven

- Fatimah Tuggar

- Jacques Villeglé

- Kara Walker

- Tom Wesselmann

Gallery

Pablo Picasso, Compotier avec fruits, violon et verre, 1912

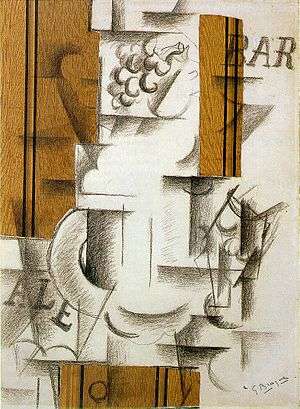

Pablo Picasso, Compotier avec fruits, violon et verre, 1912 Georges Braque, Fruitdish and Glass, 1912, papier collé and charcoal on paper

Georges Braque, Fruitdish and Glass, 1912, papier collé and charcoal on paper Jean Metzinger, Au Vélodrome, 1912, oil, sand and collage on canvas, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

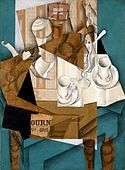

Jean Metzinger, Au Vélodrome, 1912, oil, sand and collage on canvas, Peggy Guggenheim Collection Juan Gris, Le Petit Déjeuner, 1914, gouache, oil, crayon on cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

Juan Gris, Le Petit Déjeuner, 1914, gouache, oil, crayon on cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas, Museum of Modern Art

In other contexts

In architecture

Though Le Corbusier and other architects used techniques that are akin to collage, collage as a theoretical concept only became widely discussed after the publication of Collage City (1978) by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter.

Rowe and Koetter were not, however, championing collage in the pictorial sense, much less seeking the types of disruptions of meaning that occur with collage. Instead, they were looking to challenge the uniformity of Modernism and saw collage with its non-linear notion of history as a means to reinvigorate design practice. Not only does historical urban fabric have its place, but in studying it, designers were, so it was hoped, able to get a sense of how better to operate. Rowe was a member of the so-called Texas Rangers, a group of architects who taught at the University of Texas for a while. Another member of that group was Bernhard Hoesli, a Swiss architect who went on to become an important educator at the ETH-Zurirch. Whereas for Rowe, collage was more a metaphor than an actual practice, Hoesli actively made collages as part of his design process. He was close to Robert Slutzky, a New York-based artist, and frequently introduced the question of collage and disruption in his studio work.

In music

The concept of collage has crossed the boundaries of visual arts. In music, with the advances on recording technology, avant-garde artists started experimenting with cutting and pasting since the middle of the twentieth century.

In the 1960s, George Martin created collages of recordings while producing the records of The Beatles. In 1967 pop artist Peter Blake made the collage for the cover of the Beatles seminal album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. In the 1970s and 1980s, the likes of Christian Marclay and the group Negativland reappropriated old audio in new ways. By the 1990s and 2000s, with the popularity of the sampler, it became apparent that "musical collages" had become the norm for popular music, especially in rap, hip-hop and electronic music.[15] In 1996, DJ Shadow released the groundbreaking album, Endtroducing....., made entirely of preexisting recorded material mixed together in audible collage. In the same year, New York City based artist, writer, and musician, Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky's work pushed the work of sampling into a museum and gallery context as an art practice that combined DJ culture's obsession with archival materials as sound sources on his album Songs of a Dead Dreamer and in his books Rhythm Science (2004) and Sound Unbound (2008) (MIT Press). In his books, "mash-up" and collage based mixes of authors, artists, and musicians such as Antonin Artaud, James Joyce, William S. Burroughs, and Raymond Scott were featured as part of a what he called "literature of sound." In 2000, The Avalanches released Since I Left You, a musical collage consisting of approximately 3,500 musical sources (i.e., samples).[16]

In illustration

Collage is commonly used as a technique in Children's picture book illustration. Eric Carle is a prominent example, using vividly colored hand-textured papers cut to shape and layered together, sometimes embellished with crayon or other marks. See image at The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

In artist's books

Collage is sometimes used alone or in combination with other techniques in artists' books, especially in one-off unique books rather than as reproduced images in published books.[17]

In literature

Collage novels are books with images selected from other publications and collaged together following a theme or narrative.

The bible of discordianism, the Principia Discordia, is described by its author as a literary collage. A collage in literary terms may also refer to a layering of ideas or images.

In fashion design

Collage is utilized in fashion design in the sketching process, as part of mixed media illustrations, where drawings together with diverse materials such as paper, photographs, yarns or fabric bring ideas into designs.

In film

Collage film is traditionally defined as, “A film that juxtaposes fictional scenes with footage taken from disparate sources, such as newsreels.” Combining different types of footage can have various implications depending on the director’s approach. Collage film can also refer to the physical collaging of materials onto filmstrips. Canadian Film maker, Arthur Lipsett, was especially renown for his collage films, many of which were made from the cutting room floors of the National Film Board studios.

In post-production

The use of CGI, or computer-generated imagery, can be considered a form of collage, especially when animated graphics are layered over traditional film footage. At certain moments during Amélie (Jean-Pierre Juenet, 2001), the mise en scène takes on a highly fantasized style, including fictitious elements like swirling tunnels of color and light. David O. Russel’s I Heart Huckabees (2004) incorporates CGI effects to visually demonstrate philosophical theories explained by the existential detectives (played by Lily Tomlin and Dustin Hoffman). In this case, the effects serve to enhance clarity, while adding a surreal aspect to an otherwise realistic film.

Legal issues

When collage uses existing works, the result is what some copyright scholars call a derivative work. The collage thus has a copyright separate from any copyrights pertaining to the original incorporated works.

Due to redefined and reinterpreted copyright laws, and increased financial interests, some forms of collage art are significantly restricted. For example, in the area of sound collage (such as hip hop music), some court rulings effectively have eliminated the de minimis doctrine as a defense to copyright infringement, thus shifting collage practice away from non-permissive uses relying on fair use or de minimis protections, and toward licensing.[18] Examples of musical collage art that have run afoul of modern copyright are The Grey Album and Negativland's U2.

The copyright status of visual works is less troubled, although still ambiguous. For instance, some visual collage artists have argued that the first-sale doctrine protects their work. The first-sale doctrine prevents copyright holders from controlling consumptive uses after the "first sale" of their work, although the Ninth Circuit has held that the first-sale doctrine does not apply to derivative works.[19] The de minimis doctrine and the fair use exception also provide important defenses against claimed copyright infringement.[20] The Second Circuit in October, 2006, held that artist Jeff Koons was not liable for copyright infringement because his incorporation of a photograph into a collage painting was fair use.[21]

See also

References

Bibliography

- Adamowicz, Elza (1998). Surrealist Collage in Text and Image: Dissecting the Exquisite Corpse. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59204-6.

- Ruddick Bloom, Susan (2006). Digital Collage and Painting: Using Photoshop and Painter to Create Fine Art. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80705-7.

- Museum Factory by Istvan Horkay

- History of Collage Excerpts from Nita Leland and Virginia Lee and from George F. Brommer

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bullfinch Guide to Art. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-8212-2137-X.

- Rowe, Colin; Koetter, Fred (1978). Collage City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262180863.

- Mark Jarzombek, "Bernhard Hoesli Collages/Civitas", Bernhard Hoesli: Collages, exh. cat., Christina Betanzos Pint, editor (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, September 2001), 3-11.

- Taylor, Brandon. Urban walls: a generation of collage in Europe & America: Burhan Dogançay with François Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Robert Rauschenberg, Mimmo Rotella, Jacques Villeglé, Wolf Vostell. ISBN 9781555952884; OCLC 191318119 (New York: Hudson Hills Press; [Lanham, MD]: Distributed in the United States by National Book Network, 2008)

- Excavations (Ontological Museum Acquisitions) by Richard Misiano-Genovese

Notes

- Enslen, Denise. "Origin of the term "collage"". Archived from the original on 2012-04-12.

- Collage, essay by Clement Greenberg Retrieved July 20, 2010

- Leland, Nita; Virginia Lee Williams (September 1994). "One". Creative Collage Techniques. North Light Books. p. 7. ISBN 0-89134-563-9.

- http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/exhibitions/VictPhotoColl/overview

- Art Institute of Chicago, Playing with Pictures

- "Introduction to collage". Tate Gallery website

- "Guggenheimcollection.org". Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Nature-morte à la chaise cannée Archived 2005-03-05 at the Wayback Machine - Musée National Picasso Paris

- (cf. S. Stealingworth, 1980, p. 31)

- Kurt-schwitters.org

- "Louise Nevelson, Sky Cathedral 1958". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- "Sky Cathedral", MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 222

- "This is tomorrow" Archived 2010-01-15 at the Wayback Machine, thisistomorrow2.com (scroll to "image 027TT-1956.jpg"). Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Just what is it" Archived 2008-11-21 at the Wayback Machine, pchelm.com. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Guy Garcia (June 1991). "Play It Again, Sampler". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Mark Pytlik (November 2006). "The Avalanches". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 2012-02-06. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- https://wp.vcu.edu/librarystories/2016/11/03/humphrey-gives-back-by-documenting-book-arts-and-richmond-arts-on-wikipedia/

- See Bridgeport Music, 6th Cir.

- Mirage Editions, Inc. v. Albuquerque A.R.T. Co., 856 F.2d 1341 (9th Cir. 1989)

- See the Fair Use Network for further explanations.

- Blanch v. Koons, -- F.3d --, 2006 WL 3040666 (2d Cir. Oct. 26, 2006)

External links

| Look up collage in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Collage. |

- Collageart.org, An Extensive Website devoted to the Art of Collage

- Clement Greenberg on Collage

- Exhibition of traditional and digital collage by many artists - curated by Jonathan Talbot in 2001

- Cecil Touchon's International Museum of Collage, Assemblage and Construction

- Kolaj Magazine, a print magazine about contemporary collage.

- Artist deborah harris on the process of collage

- 5 Polish Collage Artists that Knew How to Put the Pieces Together