Harry Champion

William Henry Crump (17 April 1865 – 14 January 1942), better known by the stage name Harry Champion, was an English music hall composer, singer and comedian, whose onstage persona appealed chiefly to the working class communities of East London. His best-known recordings include "Boiled Beef and Carrots" (1909), "I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1910), "Any Old Iron" (1911) and "A Little Bit of Cucumber" (1915).

Champion was born in Bethnal Green, East London. He made his stage debut at the age of 17 at the Royal Victoria Music Hall in Old Ford Road, Bethnal Green, in July 1882. He initially appeared as Will Conray and went on to appear in small music halls in the East End of London. In 1887 he changed his stage name to Harry Champion and started to perform in other parts of London where he built up a wide repertoire of songs. His trademark style was singing at a fast tempo and often about the joys of food.

After more than 4 decades on the stage, Champion took early retirement after the death of his wife in 1928, but returned two years later to appear on radio, gaining a new, much younger audience as a result. During the great depression of the 1930s, music hall entertainment had made a brief comeback, and Champion, like other performers of the genre, returned to performing. By the early 1940s he was in ill health, and died just a month after being admitted to a nursing home in 1942.

Biography

Early years, as Will Conray

Champion was born William Henry Crump on 17 April 1865 at 4 Turk Street, Bethnal Green, London, the son of Henry Crump, a master cabinet maker, and his wife, Matilda Crump, née Watson. [n 1] He had one brother and one sister. Few details are known about Champion's early life, as he was notoriously secretive.[1] When he was 15, he became an apprentice to a boot clicker and soon developed an interest in music hall entertainment.[2]

Champion made his debut at the Royal Victoria Music Hall in Old Ford Road, Bethnal Green, in July 1882, as "Will Conray, comic". He appeared in minor music halls of London's East End, where he was described as a "comic, character vocalist, character comic and dancer". In 1883 he developed a blackface act in which he sang plantation songs. Local success led him to venture into other parts of the capital in the early part of 1886.[2]

Later in 1886, Champion introduced a new act entitled From Light to Dark, in which he appeared alternately in black and whiteface. The following year he changed his stage name from Will Conray to Harry Champion.[2] When asked about the origin of the name, Champion stated:

Somebody gave it to me. It was all through a dislike the manager of the Marylebone took to me. I went on tour for a bit. When I came back, he told my agent he'd have nothing to do with me. "Right", said the agent, "but you might give a new man his chance." "Who is he?" asked the manager, and then and there my agent baptised me "Harry Champion" and came and told me afterwards.[3]

As Harry Champion

In 1889, Champion gave up the blackface part of his act. He bought the performing rights to the song "I'm Selling up the 'Appy 'Ome" which brought him newfound fame. The song is noted for being one of the first songs associated with his name. His popularity widened, and he made his West End theatre debut at the Tivoli in September 1890. Encores of his now famous song, "I'm Selling up the 'Appy 'Ome", were often accompanied with a hornpipe dance, which Champion performed. Champion followed this up with "When the Old Dun Cow Caught Fire", which he introduced into his act in 1893.[2]

By the mid-1890s, he had many songs in his repertory, and he was in demand from audiences. The Entr'Acte wrote, "Champion is a comic singer who is endowed with genuine humour, which is revealed in his several songs, of which the audience never seems to get enough".[4] His earliest known recording success was in 1896 with "In the World Turned Upside Down", followed by "Down Fell the Pony in a Fit" in 1897.[5] In 1898 Champion ceased his style of alternating songs and patter and instead adopted a quick fire delivery in order for him to perform as many songs as he could during his act. He retained this style of delivery for the remainder of his career,[2] remarking, "At one time I used to sing songs with plenty of patter but I changed the style for a new idea of my own, and started "quick singing". I think I am the only comedian who sings songs all in a lump, as you may say".[6]

Champion's popularity was at its highest from 1910 to 1915.[7] It was within this period that he introduced four of his best-known songs. "Boiled Beef and Carrots" was first published in 1909 and was composed by Charles Collins and Fred Murray. The song depicts the joys of the well known Cockney dish of the same name which was eaten frequently in London's East End community at the turn of the 20th century. "I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" was written for Champion by Fred Murray and R. P. Weston in 1910. The song is a playful reworking of the life and times of Henry VIII, in this case not the monarch, but the eighth husband of the "widow next door. She'd been married seven times before." "Any Old Iron" was written for Champion by Charles Collins, E.A. Sheppard and Fred Terry in 1911.[2] The song is about a man who inherits an old watch and chain. Champion later recorded it on the EMI label on 29 October 1935 and was accompanied by the London Palladium Orchestra. The song has often been covered by fellow artistes including Stanley Holloway and Peter Sellers.[8] "A Little Bit of Cucumber" was written by the composer T. W. Conner and was first performed by Champion in 1915. The song is about a working-class man who enjoys eating cucumbers. He later compares them to other types of food, before eventually deciding that it is cucumber he prefers. Champion later took part in the first Royal Variety Performance at The Palace Theatre in 1912.[2]

Other records of note included "What a Mouth" (1906),[9] "Everybody Knows Me in Me Old Brown Hat" and "Beaver" both from (1922).[10]

First World War and music hall decline

The titles of many of Champion's songs, supplied mainly by professional writers, centred around various types of food, consumed, chiefly by the working class community of East London.[11] Food became an essential part of his repertory,[12] so much so that during the First World War, a plate of boiled beef and carrots was known as "an 'arry Champion".[2] Champion also sang about cucumbers, pickled onions, piccalilli, saveloys, trotters, cold pork and baked sheep's heart, all basic elements in a Cockney's diet.[11]

With the outbreak of the First World War, traditional music hall entertainment declined in comparison with the new genre, variety. In 1915 Champion recorded "Grow some Taters", which was adopted by the British government's wartime publicity organisation to encourage the home growing of vegetables.[2] However, by 1918 Champion, like a lot of performers from the music hall era, found their careers on the decline[2] and he was forced into retirement in 1920.[2]

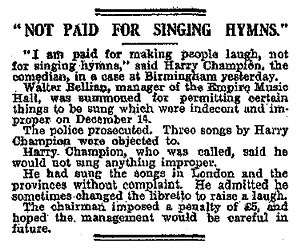

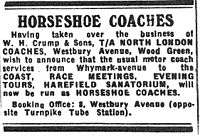

North London Coaches

Champion's main business interest away from the stage included the ownership of a successful business hiring out horse drawn Broughams to fellow performers. This evolved into a coach business in the late 1920s which became known as Horseshoe Coaches (WH Crump and sons). The business was later sold and renamed North London Coaches. Upon the outbreak of World War II, the fleet of vehicles was commandeered for the War Effort by the British government.[13]

1930s revival

During the great depression of the 1930s, music hall entertainment made a comeback and Champion like other performers of the music hall genre, returned to performing and enjoyed popularity throughout the 1930s.[2] Troupes of veterans were much in demand in the 1930s and Lew Lake's Variety, 1906–1931—Stars who Never Failed to Shine went on tour throughout the country early in the decade with Champion as a leading member.[2] Critics hailed Champion as a success stating "He almost brought the house down with three of his typical ditties".[14]

In 1932, Champion appeared at the royal variety performance with other representatives of old style music hall, including Vesta Victoria, Fred Russell and Marie Kendall.[15] That same year he returned to the London Palladium, where he sang "Any Old Iron" and had some success. Further royal variety performance appearances took place again at the Palladium in 1935[16] and at the London Coliseum in 1938,[17] and he was seen in the successful London Rhapsody with the Crazy Gang at the Palladium in 1937 and 1938.[18]

Champion decided not to try anything new because he recognised the fact that audiences liked the nostalgia surrounding his act.[2] On stage, his appearance did not change. He was the embodiment of the spirit of the poorer parts of London, wearing shabby, ill-fitting clothes, old work boots and a frayed top hat.[2] One critic noted "Like music hall itself, Harry Champion was of the people, he expressed the tastes of practically all his listeners, even those who would not openly admit it and in World War 2 he sang to troops who found him a splendid tonic".[19]

Personal life

On 30 November 1889, at St Peter's Church, Hackney, Champion married Sarah Potteweld (1869–1928), who accompanied him on many of his tours. They had three sons and a daughter. In 1914, Champion moved from the east end to 520 West Green Road, South Tottenham.[20] Towards the later part of his life he lived at 161 Great Cambridge Road, Tottenham.[20] By late 1941, exhaustion had forced him into a nursing home, at 20 Devonshire Place, St Marylebone, London.[2] He died there on 14 January 1942 and was buried with his wife (who had predeceased him on 24 January 1928) in St Marylebone cemetery, East Finchley, on 24 January 1942.[1][2][21]

Partial discography

|

|

Legacy and influence

Champion influenced many later variety artists and their acts. His songs are among some of the most popular Cockney songs ever recorded and are synonymous with people's interpretation of what Cockney humour is. "Any Old Iron" and "Boiled Beef and Carrots" are often used to illustrate a stereotype as perceived by non-cockney people.[42]

In 1960 the actor and singer Stanley Holloway recorded an album entitled Down at the Old Bull and Bush, which included a cover of "Any Old Iron". In 1965 the pop group Hermans Hermits recorded a cover of "I'm Henry VIII, I Am" for the album Hermits on Tour.[43] Champion was mentioned twice in a 1969 episode of Dad's Army in the Series 3 episode "War dance", first when music is being selected and again when Lance Corporal Jones performs various impressions of music hall artistes of the pre-First World War era but says that he cannot do an impression of Champion.[44]

"Ginger You're Barmy" which was the title of Champion's 1910 song was used as the title of a book written by the author (not to be confused with the actor of the same name) David Lodge in 1962. Chas and Dave were admirers of Champion and often emulated his style, incorporating it into their own acts. In 1984 they recorded "Harry was a Champion" in tribute to him. Actor John Rutland, long standing member of The Players Theatre London, frequently portrayed Harry Champion on the TV show The Good Old Days on BBC TV, with a chorus of singers from the Players Theatre Company and featured his songs at the Villiers Street theatre, home of The Players Theatre for many years.

On 18 November 2012, Champion's granddaughter appeared on the BBC television programme Antiques Roadshow from Falmouth, Cornwall showing a selection of Champion's music hall memorabilia which was valued upwards of £5000.[45]

Notes and references

Notes

- Some biographies have a different birth date of 8 April and a different father and mother. But research of birth records, the 1881 census data and marriage records, together with personal recollections of his Grandson Steve Crump, including dated photographs of birthday celebrations, show this is incorrect. Whilst his birth certificate only has names William Crump it is clear from marriage and death certificates that he later also adopted Henry, his father's name, as his middle name.

References

- Obituary, The Times, 15 January 1942, p. 46

- Ruskin, Alan. "Champion, Harry", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 28 October 2011.

- Disher, M.W. Costers and Cockneys – Winkles and champagne: comedies and tragedies of the music hall (1938), p. 64–5 quoted in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Entr'Acte, 13 January 1894

- Earliest mention of a Harry Champion record accessed 20 August 2011

- Barker, T. Music Hall, 26 (1982), ISSN 0143-8867, p. 35, quoted in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Harry Champion: Music Hall star, accessed 24 October 2007

- "Any Old Iron" Parlophone, catalogue no. R 4337, Jul 1957, accessed October 2011

- Song lyrics to "What a Mouth", accessed 20 August 2011

- Recording of Beaver Taken from popsike.com, accessed 20 August 2011

- Brace, Matthew."Feeding the Cockney Soul" by Matthew Brace, taken from The Independent, issued 22 May 1995, accessed October 2011

- "Harry Champion Biography", The English Music Hall, accessed 24 October 2007

- Harry Champion taxi business, accessed 21 August 2011

- The Performer, 6 May 1931

- The Royal Variety Performance Cast List of 1932 Archived 10 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 30 May 1932, accessed October 2011

- The Royal Variety Performance Cast List of 1935 Archived 10 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 29 October 1935, accessed 29 October 2011

- The Royal Variety Performance Cast List of 1938 Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine 9 November 1938, accessed 29 October 2011

- Cast list for "London Rhapsody" London Palladium, 11 October 1937, accessed 29 October 2011

- Pope, p. 406

- Directories, Stamford Hill and Tottenham, 1913–1915

- Music Hall burials (Arthur Lloyd) accessed 29 October 2007

- Regal, catalogue no. G6873, accessed October 2011

- HMV C2796, accessed October 2011

- Columbia DX289, accessed October 2011

- John Bull, cat 40791, accessed 2011

- Columbia 1650, accessed October 2011

- Columbia 1621, accessed October 2011

- Regal G6406, accessed October 2011

- John Bull, cat 40752, accessed October 2011

- Zono 595, accessed October 2011

- Columbia 1490, accessed October 2011

- Twin 517, accessed October 2011

- Zono 415, accessed October 2011

- Regal, G6403, accessed October 2011

- Regal G6403, accessed October 2011

- Zono 966, accessed October 2011

- Regal G6405, accessed October 2011

- Regal G6701, accessed October 2011

- ColIseum 864, accessed October 2011

- Regal G7357, accessed October 2011

- Regal G7772, accessed October 2011

- "A perception of who a Cockney is" taken from "In The City – A Celebration of London Music" by Paul Du Noyer, accessed 29 October 2011

- "Hermans Hermits 1965 Album", accessed August 2011

- Webber, p. 86

- "Penryn mayor's shock at Antiques Roadshow loving cup valuation" Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, This Is Cornwall website, accessed 1 December 2013.

Sources

- Webber, Richard (2003). Dad's Army: The Complete Scripts. London: Orion. ISBN 978-0-7528-6024-4.