Nantucket

Nantucket /ˌnænˈtʌkɪt/ is an island about 30 miles (50 km) by ferry[1] south from Cape Cod, in the U.S. state of Massachusetts. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town of Nantucket, and the conterminous Nantucket County. As of the 2010 census, the population was 10,172.[2] Part of the town is designated the Nantucket CDP, or census-designated place. The region of Surfside on Nantucket is the southernmost settlement in Massachusetts.

Nantucket, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| Town of Nantucket County of Nantucket | |

| |

Flag  Seal | |

Location of Nantucket County within Massachusetts | |

Nantucket Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°16′58″N 70°5′58″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| Settled | 1641 |

| Incorporated | 1671 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

| • Total | 105.3 sq mi (272.6 km2) |

| • Land | 47.8 sq mi (123.8 km2) |

| • Water | 57.5 sq mi (148.8 km2) |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 11,399 |

| • Density | 212.8/sq mi (82.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 02554, 02564, 02584 |

| Area code(s) | 508; exchanges: 228, 271, 325, 825, 332, 400 |

| FIPS code | 25-43790 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619376 |

| Website | www.nantucket-ma.gov |

The name "Nantucket" is adapted from similar Algonquian names for the island, perhaps meaning "faraway land or island" or "sandy, sterile soil tempting no one".[3]

Nantucket is a tourist destination and summer colony. Due to tourists and seasonal residents, the population of the island increases to at least 50,000 during the summer months.[4] The average sale price for a single-family home was $2.3 million in the first quarter of 2018.[5]

The National Park Service cites Nantucket, designated a National Historic Landmark District in 1966, as being the "finest surviving architectural and environmental example of a late 18th- and early 19th-century New England seaport town."[6]

History

Etymology

Nantucket probably takes its name from a Wampanoag word, transliterated variously as natocke, nantaticu, nantican, nautica or natockete, which is part of Wampanoag lore about the creation of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.[7] The meaning of the term is uncertain, although it may have meant "far away island" or "sandy, sterile soil tempting no one".[3] Wampanoag is an Eastern Algonquian language of southern New England.[8] The Nehantucket (known to Europeans as the Niantic) were an Algonquin-speaking culture people of the area.[9]

Nantucket's nickname, "The Little Grey Lady of the Sea," refers to the island as it appears from the ocean when it is fog-bound.[10][11]

European colonization

The earliest English settlement in the region began on the neighboring island of Martha's Vineyard. Nantucket Island's original Native American inhabitants, the Wampanoag people, lived undisturbed until 1641 when the island was deeded by the English (the authorities in control of all land from the coast of Maine to New York) to Thomas Mayhew and his son, merchants from Watertown, Massachusetts, and Martha's Vineyard. Nantucket was part of Dukes County, New York, until 1691, when it was transferred to the newly formed Province of Massachusetts Bay and split off to form Nantucket County. As Europeans began to settle Cape Cod, the island became a place of refuge for Native Americans in the region, as Nantucket was not yet settled by Europeans. The growing population welcomed seasonal groups of other Native Americans who traveled to the island to fish and later harvest whales that washed up on shore.[12]

Nantucket founders

In October 1641, William, Earl of Stirling, deeded the island to Thomas Mayhew of Watertown, Massachusetts Bay. In 1659 Mayhew sold an interest in the island to nine other purchasers, reserving 1/10th of an interest for himself, "for the sum of thirty pounds ... and also two beaver hats, one for myself, and one for my wife."[13]

Each of the ten original owners was allowed to invite one partner. There is some confusion about the identity of the first twenty owners, partly because William Pile did not choose a partner, and sold his interest to Richard Swain, which was subsequently divided between John Bishop and the children of George Bunker.

Anxious to add to their number and to induce tradesmen to come to the island, the total number of shares were increased to twenty-seven. The original purchasers needed the assistance of tradesmen who were skilled in the arts of weaving, milling, building and other pursuits and selected men who were given half a share provided that they lived on Nantucket and carried on their trade for at least three years.

By 1667, twenty-seven shares had been divided among 31 owners.[14]

Nantucket's settlement by the English did not begin in earnest until 1659, when Thomas Mayhew sold his interest to a group of investors, led by Tristram Coffin. The "nine original purchasers" were Tristram Coffin, Peter Coffin, Thomas Macy, Christopher Hussey, Richard Swain, Thomas Barnard, Stephen Greenleaf, John Swain and William Pike. These men are considered the founding fathers of Nantucket, and many islanders are related to these families. Seamen and tradesmen began to populate Nantucket, such as Richard Gardner (arrived 1667) and Capt. John Gardner (arrived 1672), sons of Thomas Gardner.[15]

.jpg)

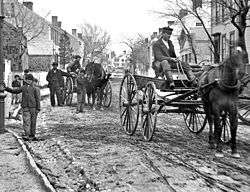

Before 1795 the town on the island was called Sherburne.[16] The original settlement was near Capaum Pond. At that time the pond was a small harbor, whose entrance silted up, forcing the settlers to dismantle their houses, and move them northeast by two miles to the present location.[17]

The whaling industry

In his 1835 history of Nantucket Island, Obed Macy wrote that in the early pre-1672 colony, a whale of the kind called "scragg" entered the harbor and was pursued and killed by the settlers.[18] This event started the Nantucket whaling industry. A. B. Van Deinse points out that the "scrag whale", described by P. Dudley in 1725 as one of the species hunted by early New England whalers, was almost certainly the gray whale, which has flourished on the west coast of North America in modern times with protection from whaling.[19][20] Nantucket's dependence on trade with England, derived from its whaling and supporting industries, influenced its leading citizens to remain neutral during the American Revolutionary War, favoring neither the British nor those supporting revolution.[21]

Herman Melville commented on Nantucket's whaling dominance in Moby-Dick, Chapter 14: "Two thirds of this terraqueous globe are the Nantucketer's. For the sea is his; he owns it, as Emperors own empires". The Moby-Dick characters Ahab and Starbuck are both from Nantucket. The tragedy that inspired Melville to write his famous novel Moby-Dick was the Final Voyage of the Essex.

By 1850, whaling was in decline, as Nantucket's whaling industry had been surpassed by that of New Bedford. The island suffered great economic hardships, worsened by the "Great Fire" of July 13, 1846, that, fueled by whale oil and lumber, devastated the main town, burning some 40 acres (16 hectares).[22] The fire left hundreds homeless and poverty-stricken, and many people left the island. Another contributor to the decline was the silting up of the harbor, which prevented large whaling ships from entering and leaving the port, unlike New Bedford, which still owned a deep water port. In addition, the development of railroads made mainland whaling ports, such as New Bedford, more attractive because of the ease of transshipment of whale oil onto trains, an advantage unavailable to an island.[23] The American Civil War dealt the death blow to the island's whaling industry, as virtually all of the remaining whaling vessels were destroyed by Confederate commerce raiders.[24]

Later history

As a result of this depopulation, the island was left under-developed and isolated until the mid-20th century. The isolation kept many of the pre-Civil War buildings intact and, by the 1950s, enterprising developers began buying up large sections of the island and restoring them to create an upmarket destination for wealthy people in the Northeastern United States.

In the 1960s, Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard considered seceding from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts which they tried in 1977, unsuccessfully. The secession vote was sparked by a proposed change to the Massachusetts Constitution that reduced the islands' representation in the Massachusetts General Court.[25]

Geology and geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 304 square miles (790 km2), of which 45 square miles (120 km2) is land and 259 square miles (670 km2) (85%) is water.[26] It is the smallest county in Massachusetts by land area and second-smallest by total area. The area of Nantucket Island proper is 47.8 square miles (124 km2). The triangular region of ocean between Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard, and Cape Cod is Nantucket Sound. Altar Rock at 100 feet (30 m),[27] Saul's Hill at 102 feet (31 m),[28] and Sankaty Head[29] at 92 feet (28 m)[28] are some of the highest points on the island.

Nantucket was formed by the outermost reach of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the recent Wisconsin Glaciation, shaped by the subsequent rise in sea level. The low ridge across the northern section of the island was deposited as glacial moraine during a period of glacial standstill, a period during which till continued to arrive and was deposited as the glacier melted at a stationary front. The southern part of the island is an outwash plain, sloping away from the arc of the moraine and shaped at its margins by the sorting actions and transport of longshore drift. Nantucket became an island when rising sea levels covered the connection with the mainland, about 5,000–6,000 years ago.[30]

The entire island, as well as the adjoining islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, comprise both the Town of Nantucket and the County of Nantucket, which are consolidated. The main settlement, also called Nantucket, is located at the western end of Nantucket Harbor, where it opens into Nantucket Sound. Key localities on the island include Madaket, Surfside, Polpis, Wauwinet, Miacomet, and Siasconset (generally shortened to "'Sconset").[31]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Nantucket features a climate that borders between a Dfb (humid continental climate) and an Cfb (oceanic climate - east half of the island based on the location of the weather station), the latter a climate type rarely found on the east coast of North America and closest to the same by the original classification.[32] Nantucket's climate is heavily influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, which helps moderate temperatures in the town throughout the course of the year. Average high temperatures during the town's coldest month (January) are around 38 °F (3 °C), while average high temperatures during the town's warmest months (July and August) hover around 75 °F (24 °C). Nantucket receives on average 41 inches (1,000 mm) of precipitation annually, spread relatively evenly throughout the year. Similar to many other cities with an oceanic climate, Nantucket features a large number of cloudy or overcast days, particularly outside the summer months. The highest daily maximum temperature was 100 °F (38 °C) on August 2, 1975, and the highest daily minimum temperature was 76 °F (24 °C) on the same day. The lowest daily maximum temperature was 12 °F (−11 °C) on January 8, 1968, and the lowest daily minimum temperature was −3 °F (−19 °C) on December 31, 1962 and January 16, 2004.

| Climate data for Nantucket, Massachusetts (Nantucket Memorial Airport) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

83 (28) |

85 (29) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

100 (38) |

86 (30) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

63 (17) |

100 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38.1 (3.4) |

39.4 (4.1) |

44.3 (6.8) |

51.3 (10.7) |

59.8 (15.4) |

68.0 (20.0) |

75.1 (23.9) |

74.7 (23.7) |

69.5 (20.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

51.9 (11.1) |

43.7 (6.5) |

56.4 (13.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.6 (−0.2) |

33.0 (0.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

44.8 (7.1) |

53.0 (11.7) |

61.7 (16.5) |

68.6 (20.3) |

68.3 (20.2) |

62.8 (17.1) |

54.2 (12.3) |

45.7 (7.6) |

37.3 (2.9) |

49.9 (9.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

38.4 (3.6) |

46.1 (7.8) |

55.5 (13.1) |

62.2 (16.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

56.2 (13.4) |

47.5 (8.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

43.4 (6.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

7 (−14) |

20 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

47 (8) |

39 (4) |

34 (1) |

22 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

−3 (−19) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.61 (92) |

2.72 (69) |

4.25 (108) |

3.74 (95) |

3.42 (87) |

3.49 (89) |

3.09 (78) |

3.91 (99) |

4.04 (103) |

3.92 (100) |

4.43 (113) |

3.80 (97) |

44.42 (1,128) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.4 (19) |

8.5 (22) |

6.6 (17) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

5.8 (15) |

29.4 (75) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 118 |

| Source 1: NOAA (1981−2010 normals)[33][34] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Western Regional Climate Center (precipitation days and snow 1948−present)[35] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 4,555 | — | |

| 1800 | 5,617 | 23.3% | |

| 1810 | 6,807 | 21.2% | |

| 1820 | 7,266 | 6.7% | |

| 1830 | 7,202 | −0.9% | |

| 1840 | 9,012 | 25.1% | |

| 1850 | 8,452 | −6.2% | |

| 1860 | 6,094 | −27.9% | |

| 1870 | 4,123 | −32.3% | |

| 1880 | 3,727 | −9.6% | |

| 1890 | 3,268 | −12.3% | |

| 1900 | 3,006 | −8.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,962 | −1.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,797 | −5.6% | |

| 1930 | 3,678 | 31.5% | |

| 1940 | 3,401 | −7.5% | |

| 1950 | 3,484 | 2.4% | |

| 1960 | 3,559 | 2.2% | |

| 1970 | 3,774 | 6.0% | |

| 1980 | 5,087 | 34.8% | |

| 1990 | 6,012 | 18.2% | |

| 2000 | 9,520 | 58.3% | |

| 2010 | 10,172 | 6.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 11,399 | [36] | 12.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[37] 1790-1960[38] 1900-1990[39] 1990-2000[40] 2010-2018[2] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 10,172 people, 4,229 households, and 2,429 families residing in the county.[41] The population density was 226.2 inhabitants per square mile (87.3/km2). There were 11,618 housing units at an average density of 258.4 per square mile (99.8/km2).[42] The racial makeup of the county was 87.6% white, 6.8% black, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% American Indian, 2.6% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 9.4% of the population.[41] In terms of ancestry, 20.9% were English, 18.8% were Irish, 11.5% were American, 10.9% were German, and 6.4% were Italian.[43]

Of the 4,229 households, 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.8% were married couples living together, 8.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 42.6% were non-families, and 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 2.93. The median age was 39.4 years.[41]

The median income for a household in the county was $83,347 and the median income for a family was $129,728. Males had a median income of $82,959 versus $46,577 for females. The per capita income for the county was $53,410. About 3.6% of families and 7.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.9% of those under age 18 and 8.2% of those age 65 or over.[44]

Government

Local

Town and county governments are combined in Nantucket (see List of counties in Massachusetts). Nantucket's elected legislative body is its Select Board (name changed in 2018 from Board of Selectmen),[45] which is responsible for the town government's goals and policies.[46] It is administered by a town manager, who is responsible for all departments, except for the school, airport and water departments.[47]

State

Nantucket is represented in the Massachusetts House of Representatives by Dylan Fernandes, Democrat, of Woods Hole, who represents Precincts 1, 2, 5 and 6, of Falmouth, in Barnstable County; Chilmark, Edgartown, Aquinnah, Gosnold, Oak Bluffs, Tisbury and West Tisbury, all in Dukes County; and Nantucket. Rep. Fernandes has served since January 4, 2017. Nantucket is represented in the Massachusetts Senate by Julian Cyr, Democrat, of Truro, who has also served since January 4, 2017.

National

Nantucket is in Massachusetts's 9th congressional district, which has existed since 2013. As of 2013, it was represented in the United States House of Representatives by Bill Keating, a Democrat of Bourne. Massachusetts is currently represented in the United States Senate by senior senator Elizabeth Warren (Democrat) and junior senator Ed Markey (Democrat).

Politics

Party affiliations

In 2019, 55% of Nantucket residents were unaligned with a major political party; 30% were registered Democrats and 12% were registered Republicans.[48]

| Voter registration and party enrollment on February 1, 2019[48] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Unenrolled* | 4,972 | 55.74% | |||

| Democratic | 2,688 | 30.13% | |||

| Republican | 1,141 | 12.79% | |||

| Independent | 67 | 0.75% | |||

| Libertarian | 38 | 0.43% | |||

| Green-Rainbow Party | 14 | 0.16% | |||

| Total | 8,920 | 100% | |||

*The Commonwealth of Massachusetts allows voters to enroll with a political party or to remain "unenrolled."[49]

Voting patterns

Throughout the late 19th and most of the 20th century, Nantucket was a Republican stronghold in presidential elections. From 1876 to 1984, only two Democrats carried Nantucket: Woodrow Wilson and Lyndon Johnson. Since 1988, however, it has trended Democratic.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 29.1% 1,892 | 63.7% 4,146 | 7.2% 470 |

| 2012 | 35.7% 2,187 | 62.6% 3,830 | 1.7% 103 |

| 2008 | 30.8% 1,863 | 67.3% 4,073 | 1.9% 116 |

| 2004 | 35.6% 2,040 | 63.0% 3,608 | 1.3% 76 |

| 2000 | 33.0% 1,624 | 58.3% 2,874 | 8.7% 428 |

| 1996 | 29.4% 1,222 | 59.0% 2,453 | 11.6% 484 |

| 1992 | 27.5% 1,158 | 48.3% 2,037 | 24.2% 1,021 |

| 1988 | 39.4% 1,469 | 59.2% 2,209 | 1.4% 53 |

| 1984 | 53.5% 1,697 | 45.9% 1,456 | 0.5% 17 |

| 1980 | 40.5% 1,149 | 36.7% 1,040 | 22.9% 649 |

| 1976 | 53.3% 1,399 | 42.5% 1,115 | 4.3% 112 |

| 1972 | 59.6% 1,418 | 40.0% 952 | 0.4% 10 |

| 1968 | 55.3% 991 | 41.5% 744 | 3.2% 57 |

| 1964 | 32.9% 587 | 67.0% 1,197 | 0.2% 3 |

| 1960 | 63.5% 1,219 | 36.4% 698 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1956 | 83.3% 1,582 | 16.7% 317 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1952 | 78.6% 1,490 | 21.4% 405 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1948 | 70.3% 1,013 | 28.4% 409 | 1.4% 20 |

| 1944 | 57.8% 779 | 42.2% 569 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1940 | 61.6% 1,015 | 37.9% 624 | 0.5% 8 |

| 1936 | 62.8% 969 | 35.5% 548 | 1.8% 27 |

| 1932 | 58.8% 812 | 40.7% 561 | 0.5% 7 |

| 1928 | 68.6% 865 | 31.3% 395 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1924 | 79.6% 708 | 18.8% 167 | 1.6% 14 |

| 1920 | 74.5% 608 | 25.1% 205 | 0.4% 3 |

| 1916 | 44.2% 249 | 54.4% 307 | 1.4% 8 |

| 1912 | 21.8% 123 | 43.8% 247 | 34.4% 194 |

| 1908 | 70.8% 359 | 26.8% 136 | 2.4% 12 |

| 1904 | 67.3% 378 | 30.3% 170 | 2.5% 14 |

| 1900 | 76.7% 375 | 20.9% 102 | 2.5% 12 |

| 1896 | 79.3% 485 | 10.1% 62 | 10.6% 65 |

| 1892 | 65.5% 440 | 32.7% 220 | 1.8% 12 |

| 1888 | 68.1% 487 | 30.1% 215 | 1.8% 13 |

| 1884 | 59.5% 328 | 37.0% 204 | 3.5% 19 |

| 1880 | 78.5% 395 | 21.5% 108 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1876 | 78.6% 379 | 21.4% 103 | 0.0% 0 |

Top employers

According to Nantucket's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[51] the top employers in the town are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Town of Nantucket | 670 |

| 2 | Nantucket Cottage Hospital | 180 |

| 3 | Nantucket Island Resorts | 125 |

| 4 | Marine Home Center | 90 |

| 5 | Stop & Shop | 90 |

| 6 | Nantucket Bank | 60 |

| 7 | Myles Reis Trucking | 30 |

| 8 | The Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority | 28 |

| 9 | Don Allen | 25 |

| 10 | Bartlett Oceanview Farm | 25 |

Education

Nantucket's public school district is Nantucket Public Schools. The Nantucket school system had 1,583 students and 137 teachers in 2017.[53]

Schools on the island include:

- Nantucket Elementary School (Public)

- Nantucket Intermediate School (Public)

- Cyrus Peirce Middle School (Public)

- Nantucket High School (Public)

- Nantucket Community School (Public, Extracurricular)

- Nantucket Lighthouse School (Private)[54]

- Nantucket New School (Private)[55]

Nantucket Public Schools District information and meetings are broadcast on Nantucket Community Television (Channel 18) in Nantucket.[56]

A major museum association, the Maria Mitchell Association, offers educational programs to the Nantucket Public Schools, as well as the Nantucket Historical Association, though the two are not affiliated.

The University of Massachusetts Boston operates a field station on Nantucket. The Massachusetts College of Art & Design is affiliated with the Nantucket Island School of Design & the Arts, which offers summer courses for teens, youth, postgraduate, and undergraduate programs.

Arts and culture

Nantucket has several noted museums and galleries, including the Maria Mitchell Association and the Nantucket Whaling Museum.

Nantucket is home to both visual and performing arts. The island has been an art colony since the 1920s, whose artists have come to capture the natural beauty of the island's landscapes and seascapes, including its flora and the fauna. Noted artists who have lived on or painted in Nantucket include Frank Swift Chase and Theodore Robinson. Artist Rodney Charman was commissioned to create a series of paintings depicting the marine history of Nantucket, which were collected in the book Portrait of Nantucket, 1659–1890: The Paintings of Rodney Charman in 1989.[57] Herman Melville based his narrative in Moby Dick on the Nantucket whaling industry.

The island is the site of a number of festivals, including a book festival, wine and food festival, comedy festival, daffodil festival,[58] and a cranberry festival.[59]

Popular culture

Several literary and dramatic works involve people from, or living on, Nantucket. These include:

- Nathaniel Philbrick's Away Off Shore: Nantucket Island and Its People, 1602–1890.

- Nathaniel Philbrick's In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

- Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.

- The science-fiction-based Nantucket series by S. M. Stirling has the island being sent back in time from March 17, 1998 to circa 1250 BC in the Bronze Age.

- Most of the Joan Aiken novel Nightbirds on Nantucket is set on the island.

- The 1971 coming-of-age film Summer of '42 was set in Nantucket.

- The 1986 comedy One Crazy Summer was set in Nantucket and filmed on Cape Cod.[60]

- The 2007 comedy The Nanny Diaries has the climax of the film take place at Mr X's Mother's Nantucket oversized Cape-Cod-styled home. Filmed in the Hamptons but made to look like Nantucket.[61]

- The 1990s sitcom Wings (a series about a fictional airline serving the airport) depicted life on Nantucket at the fictional "Tom Nevers Field" and other locations, with some of the outdoor scenes filmed at various sites on the island.

- The island's name is used as a rhyming device in a noted limerick, beginning "There once was a man from Nantucket..".

- Elin Hilderbrand's novels are set on Nantucket.

- Herman Melville's classic Moby-Dick has Ishmael starting his voyage at Nantucket

- Nantucket is the setting for the Merry Folger series of mystery novels by Francine Mathews.[62]

- American journalist Pam Belluck's 2012 non-fiction book Island Practice follows the misadventures of Nantucket doctor Timothy J. Lepore, MD.

Transportation

From 1900 to 1918, Nantucket was one of few jurisdictions in the United States that banned automobiles.[63]

Nantucket can be reached by sea from the mainland by The Steamship Authority, Hy-Line Cruises, or Freedom Cruise Line, or by private boat.[64] A task force was formed in 2002 to consider limiting the number of vehicles on the island, in an effort to combat heavy traffic during the summer months.[65]

Nantucket is served by Nantucket Memorial Airport (IATA airport code ACK), a three-runway airport on the south side of the island. The airport is one of the busiest in Massachusetts and often logs more take-offs and landings on a summer day than Boston's Logan Airport. This is due in part to the large number of private planes used by wealthy summer inhabitants, and in part to the 10-seat Cessna 402s used by several commercial air carriers to serve the island community.

Nantucket Regional Transit Authority operates seasonal island-wide shuttle buses to many destinations including Surfside Beach, Siasconset, and the airport.

Until 1917, Nantucket was served by the narrow-gauge Nantucket Railroad.

Brant Point Light in Nantucket Harbor

Brant Point Light in Nantucket Harbor

Transportation disasters

Nantucket waters were the site of several noted transportation disasters:

- On May 15, 1934, the ocean liner RMS Olympic, sister ship to RMS Titanic, rammed and sank the Nantucket Lightship LV-117 in heavy fog, roughly 45 miles south of Nantucket Island. Four men survived out of a crew of 11.

- On July 25, 1956, the Italian ocean liner SS Andrea Doria collided with the MS Stockholm in heavy fog 45 miles (72 km) south of Nantucket, resulting in the deaths of 51 people (46 on the Andrea Doria, 5 on the Stockholm).

- On December 15, 1976, the oil tanker Argo Merchant ran aground 29 miles (47 km) southeast of Nantucket. Six days later, on December 21, the wrecked ship broke apart, causing one of the largest oil spills in history.

- On October 31, 1999, EgyptAir Flight 990, traveling from New York City to Cairo, crashed approximately 60 miles (97 km) south of Nantucket, killing all 217 people on board.

National Register of Historic Places

The following Nantucket places are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:[66]

- Nantucket Historic District, a National Historic Landmark District (added December 13, 1966); Expanded to encompass the entire island in 1975.[67]

- Brant Point Light Station—Brant Point (added October 28, 1987)

- Jethro Coffin House—a National Historic Landmark, Sunset Hill Road (added December 24, 1968)

- Sankaty Head Light (added November 15, 1987)

Notable people

While many notable people own property or regularly visit the island, the following have been residents of the island:

- William Barnes Sr., attorney and Republican Party political leader[68]

- Eliza Starbuck Barney, abolitionist, genealogist[69]

- James H. Cromartie, artist

- A. J. Cronin, novelist

- James A. Folger, founder of the coffee company bearing his name

- Mayhew Folger, whaling captain

- Anna Gardner, abolitionist, poet, teacher

- Robert Moller Gilbreth, businessman, educator, and politician[70]

- Phebe Ann Coffin Hanaford, first woman ordained as a Universalist minister in New England

- Elin Hilderbrand, author

- Dorcas Honorable, last of the Nantucket Wampanoags

- Pauline Mackay, golfer

- Rowland Hussey Macy, 19th-century retailer, founder of Macy's department store

- Maria Mitchell, astronomer

- Allison Mleczko, ice hockey player

- Raymond Rocco Monto, orthopedic surgeon

- Mary Morrill, grandmother of Benjamin Franklin

- Lucretia Coffin Mott, minister, abolitionist, social reformer, and proponent of women's rights

- Cyrus Peirce, educator

- Nathaniel Philbrick, author

- Joseph Gardner Swift, first graduate of the United States Military Academy

- Meghan Trainor, singer and songwriter[71]

- Charles F. Winslow, physician, 19th-century science author

- Mary A. Brayton Woodbridge, 19th-century temperance reformer, editor

See also

References

- Tessein, Terry (2003). Fly Fishing Boston: A Complete Saltwater Guide from Rhode Island to Maine. The Countryman Press. p. 224. ISBN 9781581578652.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 19, 2001. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- "Nantucket | island, Massachusetts, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- "How many people live on Nantucket?". nantucket-ma.gov. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- Howley, Kathleen. "Real Estate Sales Smash Records on Nantucket as Wealthy Americans Buy Beach Houses". Forbes.

- Staff. "Nantucket Historic District". Maritime History of Massachusetts. National Park Service. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- Laverte, Suzanne; Orr, Tamra (2009). Massachusetts. Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7614-3005-6.

- Huden, John C. (1962). Indian Place Names of New England." New York: Museum of the American Indian. Cited in: Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names in the United States." Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pg. 312

- Swanton, John Reed (August 25, 2018). "The Indian Tribes of North America". Genealogical Publishing Com – via Google Books.

- Morris, Paul C. (July 1, 1996). Maritime Nantucket: A Pictoral History of the "Little Grey Lady of the Sea". Lower Cape Publishers. p. 272.

- Editors (August 9, 1937). "60,000 Summer visitors replace whalers on salty Martha's Vineyard & Nantucket". Life Magazine: 34–39. Retrieved April 8, 2013.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (1998). Abram's Eyes: The Native American Legacy of Nantucket Island. Nantucket: Mill Hill Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780963891082.

- Worth, Henry (1901). Nantucket Lands and Landowners (Volume 2, Issue 1 ed.). Nantucket Historical Association. pp. 53–82.

- Anderson, Florence (1940). A Grandfather for Benjamin Franklin: The True Story of a Nantucket Pioneer and His Mates. Meador. p. 183.

- Gardner, Frank A MD (1907). Thomas Gardner Planter and Some of his Descendants. Salem, MA: Essex Institute. (via Google Books)

- Brookes M.D., Richard (1819). A General Gazetteer ... Illustrated with maps ... The fifteenth edition, with considerable additions and improvements (15 ed.). London: J.Bumpus. p. 471. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "Discover Nantucket". discovernantucket.com. The Inquirer and Mirror. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Macy, Obed (1835). The History of Nantucket:being a compendious account of the first settlement of the island by the English:together with the rise and progress of the whale fishery, and other historical facts relative to said island and its inhabitants:in two parts. Boston: Hilliard, Gray & Co. ISBN 1-4374-0223-2.

- Van Deinse, A. B. (1937). "Recent and older finds of the gray whale in the Atlantic". Temminckia. 2: 161–188.

- Dudley, P (1725). "An essay upon the natural history of whales". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 33: 256–259. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0053.

- Hinchman, Lydia S. (February 1907), "William Rotch and the Neutrality of Nantucket during the Revolutionary War", Bulletin of Friends' Historical Society of Philadelphia, 1 (2): 49–55

- Kelley, Shawnie (2006). It Happened on Cape Cod. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-3824-3. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- Brown, Donna (1997-11-17). Inventing New England. Smithsonian Institution. p. 110. ISBN 9781560987994.

- Valiela, Ivan (2009-03-12). Global Coastal Change. John Wiley & Sons. p. 175. ISBN 9781444309034.

- People Section Time magazine, April 18, 1977.]

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- Wang, Amy (April 2008). Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket - Fodor's. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4000-1905-2.

- Robinson, John Henry (1910). Guide to Nantucket. Judd & Detweiler, Incorporated, printers. p. 34.

- Wilson, John Howard (1906). The glacial history of Nantucket and Cape Cod: with an argument for a fourth centre of glacial dispersion in North America. The Columbia University Press. p. 6.

- The most recent survey of the geology of Cape Cod and the islands, accessible to the layman, is Robert N. Oldale, Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard & Nantucket: The Geologic Story, 2001.

- Karttunen, Frances Ruley (2005). The Other Islanders: People Who Pulled Nantucket's Oars. Spinner Publications. p. 304. ISBN 0932027938.

- Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "MA Nantucket MEM AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "General Climate Summary Tables". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- "Nantucket Selectmen go gender-neutral". Inquirer & Mirror website.

- "Board of Selectmen". Town and County of Nantucket website. Archived from the original on July 22, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- "Town Administration". Town and County of Nantucket website. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of February 1, 2019" (PDF). Massachusetts Elections Division. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (December 21, 2015). "Massachusetts Directory of Political Parties and Designations". Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- Turbitt, Brian E. (October 9, 2018). "Town of Nantucket, Massachusetts Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018" (PDF). Town of Nantucket, Massachusetts. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- Finger, Jascin Leonardo. "The History of The Coffin School". Nantucket, Massachusetts: Nantucket Preservation Trust. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "2017 NCLB Report Card - Nantucket". No Child Left Behind Reports. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

- "The Nantucket Lighthouse School". Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- "The Nantucket New School". Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- "Nantucket Community Television – Broadcasting Nantucket. Vision. Voice. Life". nantucketcommunitytelevision.org.

- Mooney, Robert E. (1996-12-12). Portrait of Nantucket, 1659-1890: The Paintings of Rodney Charman. Mill Hill Press. ISBN 9780963891037.

- Staff. "Nantucket Celebrates 45th Annual Daffodil Weekend | CapeCodToday.com". capecodtoday.com. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- "Nantucket Festivals". nantucket.net. Yesterday's Island, Inc. 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- Gelbert, Doug (2002). Film and Television Locations: a State-by-State Guidebook to Moviemaking sites, excluding Los Angeles. McFarland & Company. p. 111.

- https://hookedonhouses.net/2011/09/19/the-nanny-diaries-an-upper-east-side-apartment-and-a-nantucket-beach-house/

- page 161–164, Great Women Mystery Writers, 2nd Ed. by Elizabeth Blakesley Lindsay, 2007, publ. Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33428-5

- "Flickr". Flickr.

- "Business Directory Search - Nantucket Island Chamber of Commerce, MA". www.nantucketchamber.org.

- Nantucket 'gridlock' spurs plan to limit cars on island. CapeCodOnline.com (2002-05-07). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- "National Register of Historical Places - MASSACHUSETTS (MA), Nantucket County". www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com.

- "Nantucket's National Historic Landmark Update Gains Advisory Committee Approval - Nantucket Preservation Trust". www.nantucketpreservation.org.

- New York State Bar Association (1913). Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth Annual Meeting. Albany, NY: The Argus Company. pp. 713–716 – via Google Books.

- Stout, Kate. ""Who Was Eliza Barney?"". www.nha.org. Nantucket Historical Association. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "The Gilbreth Network: That Most Famous Dozen". gilbrethnetwork.tripod.com.

- Globe correspondent (September 16, 2014), "All about Nantucket's Meghan Trainor", Boston Globe, Style, retrieved 2015-09-04

Notes

- Bond, C. Lawrence, Native Names of New England Towns and Villages, privately published by C. Lawrence Bond, Topsfield, Massachusetts, 1991.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel, In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, Penguin, NY, NY, 2000.

- I Once Had a Chum from Nantucket by Drs. Ernest and Convalescence Bidet-Wellville on Neatorama

- Fabrikant, Geraldine, "Old Nantucket Warily Meets the New", New York Times, June 5, 2005

- 36 Hours in Nantucket in the New York Times of July 18, 2010

Further reading

- Macy, William Francis (1915). The Story of Old Nantucket: A Brief History of the Island and its People from its Discovery down to the Present Day. Nantucket: The Inquirer and Mirror Press.

- Tower, W. S. (1907). A History of the American Whale Fishery. University of Philadelphia.

External links

![]()

![]()