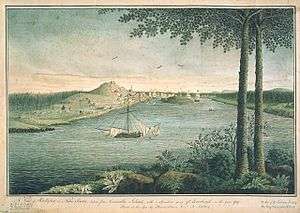

Louisbourg Expedition (1757)

The Louisbourg Expedition (1757) was a failed British attempt to capture the French Fortress of Louisbourg on Île Royale (now known as Cape Breton Island) during the Seven Years' War (known in the United States as the French and Indian War).

Background

The French and Indian War started in 1754 over territorial disputes between the North American colonies of France and Great Britain in areas that are now western Pennsylvania and upstate New York. The first few years of the war had not gone particularly well for the British. A major expedition by General Edward Braddock in 1755 ended in disaster, and British military leaders were unable to mount any campaigns the following year. In a major setback, a French and Indian army led by General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm captured the garrison and destroyed fortifications in the Battle of Fort Oswego in August 1756.[1] In July 1756, the Earl of Loudoun arrived to take command of the British forces in North America, replacing William Shirley who had temporarily assumed command after Braddock's death.[2]

British planning

Loudoun's plan for the 1757 campaign was submitted to the government in London in September 1756, focused on a single expedition aimed at the heart of New France in the city of Quebec. It called for a purely defensive posture along the frontier with New France, including the contested corridor of the Hudson River and Lake Champlain between Albany, New York and Montreal.[3] Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec, so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of the province of Canada along the Saint Lawrence River.[4] However, there was political turmoil in London over the progress of the Seven Years' War, both in North America and in Europe, and this resulted in a change of power, with William Pitt the Elder rising to take control over military matters. Loudoun consequently did not receive any feedback from London on his proposed campaign until March 1757.[3] Before this feedback arrived, he developed plans for the expedition to Quebec and worked with the provincial governors of the Thirteen Colonies to develop plans for a coordinated defence of the frontier, including the allotment of militia quotas to each province.[5]

William Pitt's instructions finally reached Loudoun in March 1757. They called for the expedition to first target Louisbourg on the Atlantic coast of Île Royale, now known as Cape Breton Island.[6] Loudoun was to command the land forces, while a squadron under Francis Holburne would transport the troops and face any French naval threats.

French preparations

French military leaders had early intelligence that the British were planning an expedition, and they also learned at an early date that Louisbourg would be the target. Between January and April 1757, squadrons sailed from Brest and Toulon, some of which went to reinforce the squadron based at Louisbourg.

Dubois de La Motte commanded a squadron of nine ships of the line and two frigates at Louisbourg, which was joined by that of Joseph de Bauffremont from Saint-Domingue with five ships of the line and a frigate, and four ships and two frigates from Toulon under Joseph-François de Noble Du Revest.[7]

French fleet: order of battle

|

Under the orders of Noble du Revest :

|

Under the orders of Chevalier de Beauffremont :

|

Under the orders of du Dubois de La Motte :

|

The frigates were :

|

Hurricane

Admiral Holburne was aware of the arrival of French reinforcements, but the expedition was not yet ready and only sailed in early August. By the middle of the month, his ships were patrolling off Louisbourg, but Dubois de La Motte chose to stay in the harbor. As the days progressed, the weather deteriorated.

On 24 September 1757, the British fleet was scattered by a gale, but the French could not pursue them due to a typhus epidemic.[7] Dubois de La Motte returned to Brest with his sick men on 30 October 1757.[7][8]

Aftermath

The British succeeded in capturing Louisbourg the following year.

There were significant consequences in the frontier war because of the delays in Loudoun's instructions and the redirection of the expedition to Louisbourg instead of Quebec. Because Quebec was not targeted, the leaders of New France were able to use forces in operations against Fort William Henry which would otherwise have been needed to defend Quebec—and Loudoun had left Fort William Henry minimally defended in order to man his expedition. In August 1757, General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm led a force of 8,000, including 1,800 Indians, against the British fort, and the British surrendered after a short siege. After the surrender, the French-allied Indians harassed and eventually attacked the defenceless retreating British, taking many captives and brutally slaying wounded soldiers. The incident was one of the most controversial events of the war.

See also

Notes

- Steele, pp. 28–56

- Parkman, p. 397

- Pargellis, p. 211

- Pargellis, p. 243

- Pargellis, pp. 212–215

- Pargellis, p. 232

- Encyclopedia of the French & Indian War in North America, 1754–1763 by Donald I. Stoetzel p.61

- Naval Chronicle

References

- Pargellis, Stanley McRory (1933). Lord Loudoun in North America. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 460019682.

- Parkman, Francis (1922) [1884]. Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 30767445.

- Steele, Ian K (1990). Betrayals: Fort William Henry & the 'Massacre'. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505893-2. OCLC 20098712.