Architecture of Bengal

The architecture of Bengal, which comprises the modern country of Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley, has a long and rich history, blending indigenous elements from the Indian subcontinent, with influences from different parts of the world. Bengali architecture includes ancient urban architecture, religious architecture, rural vernacular architecture, colonial townhouses and country houses and modern urban styles. The bungalow style is a notable architectural export of Bengal. The corner towers of Bengali religious buildings were replicated in medieval Southeast Asia. Bengali curved roofs, suitable for the very heavy rains, were adopted into a distinct local style of Indo-Islamic architecture, and used decoratively elsewhere in north India in Mughal architecture.

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

Bengali culture

|

|

Bengali symbols |

Bengal is not rich in good stone for building, and traditional Bengali architecture mostly uses brick and wood, often reflecting the styles of the wood, bamboo and thatch styles of local vernacular architecture for houses. Decorative carved or moulded plaques of terracotta (the same material as the brick) are a special feature. The brick is extremely durable and disused ancient buildings were often used as a convenient source of materials by local people, often being stripped to their foundations over the centuries.

Antiquity and Buddhism

Urbanization is recorded in the region since the first millennium BCE. This was part of the second wave of urban civilization in the Indian subcontinent, following the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization. Ancient Bengal was part of a network of urban and trading hubs stretching to Ancient Persia. The archaeological sites of Mahasthangarh, Paharpur, Wari-Bateshwar ruins, Chandraketugarh and Mainamati provide evidence of a highly organized urban civilization in the region. Terracotta became a hallmark of Bengali construction, as the region lacked stone reserves. Bricks were produced with the clay of the Bengal delta.

Ancient Bengali architecture reached its pinnacle during the Pala Empire (750–1120); this was Bengali-based and the last Buddhist imperial power in the Indian subcontinent. Most patronage was of Buddhist viharas, temples and stupas. Pala architecture influenced Tibetan and Southeast Asian architecture. The most famous monument built by the Pala emperors was the Grand Vihara of Somapura, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Historians believe Somapura was a model for the architects of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.[1]

Medieval and early modern periods

Hindu and Jain

Bengal was one of the last strongholds of Buddhism in the medieval period, and Hindu temples before the Muslim conquest (starting in 1204) were relatively small. The Hindu Sena dynasty only ruled for a century before the conquest. They built the relatively modest Dhakeshwari Temple in Dhaka, although this has been greatly rebuilt.

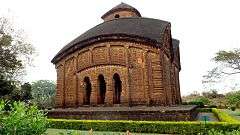

The term deula, deul (or deoul) is used for a style of Jain and Hindu temple architecture of Bengal, where the temple lacks the usual mandapa beside the main shrine, and the main unit consists only of the shrine and a deul above it. The type arose between the 6th and 10th centuries, and most examples are now ruins; it was revived in the 16th to 19th century.[2] In other respects they are similar to the Kalinga architecture of Odisha, where the term is also used for temple superstructures - what would be called a shikara elsewhere in northern India.[3] and some smaller temples in Odisha take this form. The later representatives of this style were generally smaller and included features influenced by Islamic architecture.[2]

Most temples surviving in reasonable condition date from about the 17th century onwards, after temple building revived; it had stopped after the Muslim conquest in the 13th century.[4] The roofing style of Bengali Hindu temple architecture is unique and closely related to the paddy roofed traditional building style of rural Bengal.[5] The "extensive improvisation within a local architectural idiom"[6] which the temples exhibit is often ascribed to a local shortage of expert Brahmin priests to provide the rather rigid guidance as to correct forms that governed temple architecture elsewhere. In the same way the terracotta reliefs often depict secular subjects in a very lively fashion.

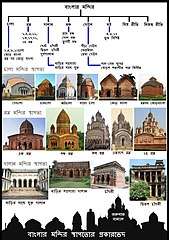

Roofing styles include the jor-bangla, do-chala, char-chala, at-chala, and ek-ratna. The do-chala type has only two hanging roof tips on each side of a roof divided in the middle by a ridge-line; in the rare char-chala type, the two roof halves are fused into one unit and have a dome-like shape; the double-storey at-chala type has eight roof corners.[7][2]

Many of these temples are covered on the outer walls with terracotta (carved brick) reliefs. Bishnupur in West Bengal has a remarkable set of 17th and 18th-century temples with a variety of roof styles built by the Malla dynasty.

In larger, and later, temples, small towers rise up from the centre or corners of the curving roof. These are straight-sided, often with conical roofs. They have little resemblance to a typical north Indian shikara temple tower. The pancharatna ("five towers") and navaratna ("nine towers") styles are varieties of this type.[2]

The temple structures contain gabled roofs which are colloquially called the chala, For example, a gabled roof with an eight sided pyramid structured roof will be called "ath chala" or literally the eight faces of the roof. And frequently there is more than one tower in the temple building. These are built of laterite and brick bringing them at the mercy of severe weather conditions of southern Bengal. Dakshineswar Kali Temple is one example of the Bhanja style while the additional small temples of Shiva along the river bank are example of southern Bengal roof style though in much smaller dimension.

.jpg) A deul Jain temple

A deul Jain temple- A Pancharatna temple

- A ritual platform

Ram Chandra Temple on Guptipara

Ram Chandra Temple on Guptipara Jor-bangla features a curved Do-chala style roof

Jor-bangla features a curved Do-chala style roof Evolution of Temple Architecture in Bengal

Evolution of Temple Architecture in Bengal Classification of Bengal Temple Architecture 1

Classification of Bengal Temple Architecture 1 Classification of Bengal Temple Architecture 2

Classification of Bengal Temple Architecture 2

Islamic

.jpg)

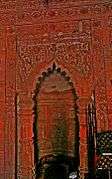

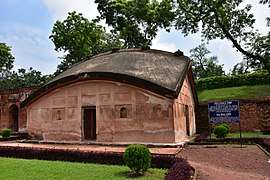

Indo-Islamic architecture in the Bengali architecture can be seen from the 13th century, but before the Mughals has usually strongly reflected local traditions. The oldest surviving mosque was built during the Delhi Sultanate. The mosque architecture of the independent Bengal Sultanate period (14th, 15 and 16th centuries) represents the most important element of the Islamic architecture of Bengal. This distinctive regional style drew its inspiration from the indigenous vernacular architecture of Bengal, including curved chala roofs, corner towers and complex floral carvings. Sultanate-era mosques featured multiple domes or a single dome, richly designed mihrabs and minbars and an absence of minarets. While clay bricks and terracotta were the most widely used materials, stone was used from mines in the Rarh region. The Sultanate style also includes gateways and bridges. The style is widely scattered across the region.[8]

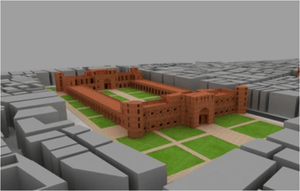

Mughal Bengal saw the spread of Mughal architecture in the region, including forts, havelis, gardens, caravanserais, hammams and fountains. Mughal Bengali mosques also developed a distinct provincial style. Dhaka and Murshidabad were the hubs of Mughal architecture. The Mughals copied the do-chala roof tradition in North India.[9]

Bengal Sultanate

The Bengal Sultanate (1352–1576) normally used brick as the primary construction material, as pre-Islamic buildings had done.[10] Stone had to be imported to most of Bengal, whereas clay for bricks is plentiful. But stone was used for columns and prominent details, often re-used from Hindu or Buddhist temples.[11] The early 15th century Eklakhi Mausoleum at Pandua, Malda or Adina, is often taken to be the earliest surviving square single-domed Islamic building in Bengal, the standard form of smaller mosques and mausoleums. But there is a small mosque at Molla Simla, Hooghly district, that is probably from 1375, earlier than the mausoleum.[12] The Eklakhi Mausoleum is large and has several features that were to become common in the Bengal style, including a slightly curved cornice, large round decorative buttresses and decoration in carved terracotta brick.[13]

These features are also seen in the Choto Sona Mosque (around 1500), which is in stone, unusually for Bengal, but shares the style and mixes domes and a curving "paddy" roof based on village house roofs made of vegetable thatch. Such roofs feature even more strongly in later Bengal Hindu temple architecture, with types such as the do-chala, jor-bangla, and char-chala.[14] For larger mosques, Bengali architects multiplied the numbers of domes, with a nine-domed formula (three rows of three) being one option, surviving in four examples, all 15th or 16th century and now in Bangladesh,[15] although there were others with larger numbers of domes.[16]

Buildings in the style are the Nine Dome Mosque and the Sixty Dome Mosque (completed 1459) and several other buildings in the Mosque City of Bagerhat, an abandoned city in Bangladesh now featured as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. These show other distinctive features, such as a multiplicity of doors and mihrabs; the Sixty Dome Mosque has 26 doors (11 at the front, 7 on each side, and one in the rear). These increased the light and ventilation. Further mosques include the Baro Shona Masjid; the Pathrail Mosque, the Bagha Mosque, the Darasbari Mosque, and the Kusumba Mosque. Single-domed mosques include the Singar Mosque, and the Shankarpasha Shahi Masjid.

Both capitals of the Bengal Sultanate, first Pandua or Adina, then from 1450 Gauda or Gaur, started to be abandoned soon after the conquest of the sultanate by the Mughals in 1576, leaving many grand buildings, mostly religious. The materials from secular buildings were recycled by builders in later periods.[17] While minarets are conspicuously absent in most mosques, the Firoz Minar was built in Gauda to commemorate Bengali military victories.

The ruined Adina Mosque (1374–75) is very large, which is unusual in Bengal, with a barrel vaulted central hall flanked by hypostyle areas. It is said to be the largest mosque in the sub-continent, and modeled after the Ayvan-e Kasra of Ctesiphon, Iraq, as well as the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus.[18] The heavy rainfall in Bengal necessitated large roofed spaces, and the nine-domed mosque, which allowed a large area to be covered, was more popular there than anywhere else.[19] After the Islamic consolidation of Bengal was complete, some local features continued, especially in smaller buildings, but the Mughals used their usual style in imperial commissions.[20]

A multi-domed Sultanate era mosque

A multi-domed Sultanate era mosque A Bengali mihrab

A Bengali mihrab A 17th century haveli in Old Dhaka

A 17th century haveli in Old Dhaka The Naulakha Pavilion at the Lahore Fort in Pakistan displays the distinct Bengali Do-chala style roof.[21]

The Naulakha Pavilion at the Lahore Fort in Pakistan displays the distinct Bengali Do-chala style roof.[21] 3D model of a reconstructed Bara Katra (Great Caravanserai of Dhaka) from the Mughal era

3D model of a reconstructed Bara Katra (Great Caravanserai of Dhaka) from the Mughal era Mughal era domes in Murshidabad

Mughal era domes in Murshidabad A Sultanate era gateway

A Sultanate era gateway A Sultanate era standalone minaret

A Sultanate era standalone minaret A Sultanate era arch

A Sultanate era arch A Sultanate era stone mosque

A Sultanate era stone mosque- An early Sultanate era mosque and tomb

- The Sultanate era Adina Mosque

Interior of a Sultanate era imperial mosque

Interior of a Sultanate era imperial mosque A Sultanate era mausoleum

A Sultanate era mausoleum A Sultanate era stone mosque

A Sultanate era stone mosque.jpg) A Mughal era bridge in Sonargaon

A Mughal era bridge in Sonargaon South-East Gate of Lalbagh Fort in 1875

South-East Gate of Lalbagh Fort in 1875

British Colonial period

The period of British rule saw wealthy Bengali families (especially zamindar estates) employing European firms to design houses and palaces. The Indo-Saracenic movement was strongly prevalent in the region. While most rural estates featured an elegant country house, the cities of Calcutta, Dacca, Panam and Chittagong had widespread 19th and early 20th century urban architecture, comparable to London, Sydney or Auckland. Art deco influences began in Calcutta in the 1930s.

Neoclassical

Indo-Saracenic

Victoria Memorial is a famous example is Indo-sarasenic architecture.

Victoria Memorial is a famous example is Indo-sarasenic architecture.

Indian Museum, the oldest Museum in subcontinent.

Indian Museum, the oldest Museum in subcontinent. Hazarduari Palace, Murshidabad

Hazarduari Palace, Murshidabad

Indo-Saracenic architecture can be seen in the Ahsan Manzil and Curzon Hall in Dhaka, Chittagong Court Building in Chittagong, and Hazarduari Palace in Murshidabad. The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, designed by Vincent Esch also has Indo-Saracenic features, possibly inspired from the Taj Mahal.

Bungalows

The origin of the bungalow has its roots in the vernacular architecture of Bengal.[23] The term baṅgalo, meaning "Bengali" and used elliptically for a "house in the Bengal style".[24] Such houses were traditionally small, only one storey and detached, and had a wide veranda were adapted by the British, who used them as houses for colonial administrators in summer retreats in the Himalayas and in compounds outside Indian cities.[25] The Bungalow style houses are still very popular in the rural Bengal. In the rural areas of Bangladesh, it is often called “Bangla Ghar” (Bengali Style House). The main construction material used in modern time is corrugated steel sheets. Previously they had been constructed from wood, bamboo and a kind of straw called “Khar”. Khar was used in the roof of the Bungalow house and kept the house cold during hot summer days. Another roofing material for Bungalow houses has been red clay tiles.

Modernism

- An art deco building in Chittagong

Bangladeshi rooftop garden

Bangladeshi rooftop garden A Rubik's cube style building in Dhaka

A Rubik's cube style building in Dhaka

.jpg)

Art Deco influences continued in Chittagong during the 1950s. East Pakistan was the center of the Bengali modernist movement started by Muzharul Islam. Many renowned global architects worked in the region during the 1960s, including Louis Kahn, Richard Neutra, Stanley Tigerman, Paul Rudolph, Robert Boughey and Konstantinos Doxiadis. Louis Kahn designed the Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban, the preeminent symbol of modern Bangladeshi architecture. The cityscapes of modern Bengali cities are dominated by midsized skycrapers and often called concrete jungles. Architecture services form a significant part of urban economies in the region, with acclaimed architects such as Rafiq Azam.

In 2015, Marina Tabassum and Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury were declared winners of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for their mosque and community center designs respectively, which were inspired by the region's ancient heritage.[28]

Notes

- Ronald M. Bernier (1997). Himalayan Architecture. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 22. ISBN 978-0-8386-3602-2.

- Amit Guha, Classification of Terracotta Temples, archived from the original on 31 January 2016, retrieved 30 January 2016

- Harle, 216

- Michell, 156

- 3.http://www.kamat.com/kalranga/wb/wbtemps.htm

- Michell, 156

- "Architecture". Banglapedia. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- Perween Hasan; Oleg Grabar (2007). Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

- Andrew Petersen (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-134-61365-6.

- Banglapedia

- Hasan, 34-35

- Hasan, 36-39

- Hasan, 36-37; Harle, 428

- Hasan, 23-25

- Hasan, 41-44

- Hasan, 44-49

- Banglapedia

- "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- Hasan, 35-36, 39

- Banglapedia

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich; Unesco (2003-01-01). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

- Chaudhuri, Amit (2015-07-02). "Calcutta's architecture is unique. Its destruction is a disaster for the city". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- bungalow > common native dwelling in the Indian province of Bengal

- Oxford English Dictionary, "bungalow"; Online Etymology Dictionary

- Bartleby.com

- Singh, Shiv Sahay; Bagchi, Suvojit (2015-06-27). "The old Calcutta chromosomes". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- Guha, Divya (2015-08-25). "The fight to save Kolkata's heritage homes". BBC. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- http://www.dhakatribune.com/feature/2016/10/03/2-bangladeshi-projects-among-aga-khan-award-for-architecture-winners/

References

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Hasan, Perween, Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh, 2007, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1845113810, 9781845113810, google books

- Michell, George, (1977) The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Meaning and Forms, 1977, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1

Further reading

- Michell, George (Ed.), Brick Temples of Bengal - From the Archives of David McCutchion, Princeton University press, New Jersey, 1983

- Becker-Ritterspach, Raimund O.A., Ratna style Temples with an Ambulatory - Selected temple concepts in Bengal and the Kathmandu Valley, Himal Books, Kathmandu, 2016, ISBN 978 9937 597 29 6