Chalk Group

The Chalk Group (often just called the Chalk) is the lithostratigraphic unit (a certain number of rock strata) which contains the Late Cretaceous limestone succession in southern and eastern England. The same or similar rock sequences occur across the wider northwest European chalk 'province'. It is characterised by thick deposits of chalk, a soft porous white limestone, deposited in a marine environment.

| Chalk Group Stratigraphic range: Cenomanian to Maastrichtian 100–66 Ma | |

|---|---|

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1272999.jpg) Brass Point, one of the Seven Sisters | |

| Type | Group |

| Sub-units | Cambridge Greensand Grey Chalk Subgroup, White Chalk Subgroup |

| Underlies | unconformity, Thanet Formation, Lambeth Group |

| Overlies | Selborne Group, Hunstanton Formation, Cambridge Greensand |

| Thickness | over 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | limestone |

| Other | mudstone, flint |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| Extent | southern and eastern England |

Chalk is a limestone that consists of coccolith biomicrite.[1] A biomicrite is a limestone composed of fossil debris ("bio") and calcium carbonate mud ("micrite"). Most of the fossil debris in chalk consists of the microscopic plates, which are called coccoliths, of microscopic green algae known as coccolithophores. In addition to the coccoliths, the fossil debris includes a variable, but minor, percentage of the fragments of foraminifera, ostracods and mollusks. The coccolithophores lived in the upper part of the water column. When they died, the microscopic calcium carbonate plates, which formed their shells settled downward through the ocean water and accumulated on the ocean bottom to form a thick layer of calcareous ooze, which eventually became the Chalk Group.

The Chalk Group usually shows few signs of bedding, other than lines of flint nodules which become common in the upper part. Nodules of the mineral pyrite also occur and are usually oxidized to brown iron oxide on exposed surfaces.

Well-known outcrops include the White Cliffs of Dover, Beachy Head, the southern coastal cliffs of the Isle of Wight and the quarries and motorway cuttings at Blue Bell Hill, Kent, (which has been classified as a Site of Special Scientific Interest) and at the Stokenchurch Gap on the Oxfordshire/Buckinghamshire border where the M40 motorway cuts through the Aston Rowant National Nature Reserve.

Subdivisions

The Chalk Group is now divided into a White Chalk Subgroup and a Grey Chalk Subgroup, both of which are further subdivided into formations. These modern divisions replace numerous earlier divisions, references to which occur widely on geological maps and in other geological literature. Previously no subgroups were defined but three formations were identified; the Upper Chalk, Middle Chalk and Lower Chalk. Different formations are defined within the 'northern' and 'southern' provinces, from Norfolk northwards and south of the Thames valley respectively. A 'transitional province' between the two and covering much of East Anglia and the Chiltern Hills is also recognised. A different approach again is taken as regards the succession beneath the North Sea.[2]

Grey Chalk Subgroup

The Grey Chalk Subgroup (formerly the Lower Chalk minus the Plenus Marls) is usually relatively soft and greyish in colour. It is also the most fossiliferous (especially for ammonite fossils). The strata of this subgroup usually begin with the 'Glauconitic Marl Member' (formerly known as the Glauconitic or Chloritic Marl), named after the grains of the green minerals glauconite and chlorite which it contains. The remainder of the subgroup is argillaceous in its lower part (the West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation (formerly the 'Chalk Marl') and becomes progressively purer in the 'Zig-zag Chalk Formation' (the former 'Grey Chalk'). In the central Chilterns the two parts are separated by the hard Totternhoe Stone, which forms a prominent scarp in some places. There are few, if any, flint nodules present.

These two formations are not recognised within the northern province i.e. the outcrop north from East Anglia to Yorkshire, where the entire sequence is now referred to as the 'Ferriby Chalk Formation'. The thickness of the Grey Chalk Subgroup strata varies, averaging around 200 ft (61 m), depending upon the location. They often contains fossils such as the ammonites Schloenbachia, Scaphites, and Mantelliceras, the belemnite Actinocamax, and the bivalves Inoceramus and Ostrea.

White Chalk Subgroup

The White Chalk Subgroup includes what were formerly designated the Middle Chalk and Upper Chalk Formations, together with the Plenus Marls (topmost part of the former Lower Chalk Formation). In the southern province it is divided in the following way (youngest/uppermost at top):

- Portsdown Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk' and the equivalent of Rowe Chalk Formation, below)

- Culver Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Spetisbury Chalk Member (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Tarrant Chalk Member (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Newhaven Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Seaford Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Lewes Nodular Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- New Pit Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Middle Chalk')

- Holywell Nodular Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Middle Chalk')

- Plenus Marls Member

In the northern province the sequence is divided thus:

- Rowe Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk' and the equivalent of Portsdown Chalk Formation, above)

- Flamborough Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Burnham Chalk Formation (formerly part of 'Upper Chalk')

- Welton Chalk Formation (formerly 'Middle Chalk')

- Plenus Marls Member

In the southern province, the former Middle Chalk, now the Holywell Nodular Chalk Formation and overlying New Pit Formation, averages about 200 ft (61 m) in thickness. The sparse fossils found in this sequence include the brachiopod Terebratulina and the echinoid Conulus.

The former Upper Chalk by comparison is softer than the underlying sequence and the flint nodules it contains are far more abundant in the South of England, although in Yorkshire the underlying strata have the highest concentration of flints. It may contain ammonite and gastropod fossils in some nodular layers. The thickness of this sequence varies greatly, often averaging around 300 ft (91 m). Fossils may be abundant and include the bivalve Spondylus, the brachiopods Terebratulina and Gibbithyris, the echinoids Sternotaxis, Micraster, Echinocorys, and Tylocidaris, the crinoid Marsupites, and the small sponge Porosphaera.

The youngest beds of the sequence are found on the coast of Norfolk. Other fossils commonly found in this formation include: solitary corals (such as Parasmilia), marine worm tubes (such as Rotularia), bryozoans, scattered fragments of starfish and fish remains (including shark teeth such as Cretolamna and Squalicorax).

Chalk landscapes of England

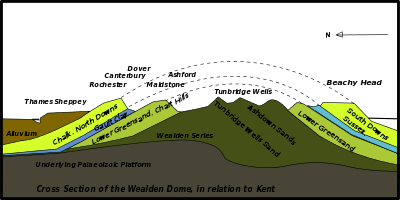

The Chalk outcrops across large parts of southern and eastern England and forms a significant number of the major physiographical features. Whilst it has been postulated that a chalk cover was laid down across just about all of England and Wales during Cretaceous times, subsequent uplift and erosion has resulted in it remaining only southeast of a line drawn roughly between The Wash and Lyme Bay in Dorset and eastwards from the scarps of the Lincolnshire and Yorkshire Wolds. Gentle folding of the Mesozoic rocks of this region during the Alpine orogeny has produced the London Basin and the Weald–Artois Anticline, the Hampshire Basin and the less gentle Purbeck-Wight monocline.

The broadly western margin of the Chalk outcrop is marked, from northeast to southwest, to south by the Chalk downlands of the Yorkshire Wolds, the Lincolnshire Wolds, a subdued feature through western Norfolk, including Breckland, the Chiltern Hills, the Berkshire Downs, Marlborough Downs and the western margins of Salisbury Plain and Cranborne Chase and the North and South Dorset Downs.[3] In parts of the Thames Basin and eastern East Anglia the Chalk is concealed by later deposits, as is the case too within the Hampshire Basin.

Only where the Weald–Artois Anticline has been 'unroofed' by erosion i.e. within the Weald is the Chalk entirely absent. In this area the long south-facing scarp of the North Downs and the longer north-facing scarp of the South Downs face one another across the Weald. For similar reasons, the Chalk is largely absent from the rather smaller area to the south of the Purbeck-Wight Monocline, save for the downs immediately north of Ventnor on the Isle of Wight.

Some of the best exposures of the Chalk are where these ranges intersect the coast to produce dramatic, often vertical cliffs as at Flamborough Head, the White Cliffs of Dover, Seven Sisters, Old Harry Rocks (Purbeck) and The Needles on the Isle of Wight. The Chalk, which once extended across the English Channel, gives rise to similar cliff features on the French coast.

Offshore and elsewhere

Northern Ireland

In the 'Ulster Cretaceous Province' of Northern Ireland the clastic-dominated Hibernian Greensands Group and the overlying Ulster White Limestone Group are the stratigraphical equivalents of the Chalk Group of England. They are best exposed near the Antrim coast.

Scotland

In the 'Scottish Chalk Province' (extending from Mull to Skye) the Inner Hebrides Group is the stratigraphical equivalent of England's Chalk Group. It comprises largely sandstones and mudstones though the Santonian age Gribun Chalk Formation of Mull and nearby Morvern is recognised.

The Low Countries

The Dutch (Dutch: Krijtkalk-Groep) and Belgian (Dutch: Krijt-Groep) equivalents of the Chalk Group are basically continuous and crop out as a slightly northwest dipping monocline in a belt from the German city of Aachen to the city of Mons, where they join Cretaceous deposits of the Paris Basin. North of Namur the Cretaceous is overlain by younger Paleocene and Eocene deposits of the Landen Group.

In the Low Countries, the Chalk Group succession is divided into five formations, from top to base:[4]

- the Houthem Formation, consisting of Paleocene calcareous arenites;

- the Maastricht Formation, consisting of Maastrichtian chalk and calcareous arenites;

- the Gulpen Formation, consisting of Campanian to Maastrichtian chalk;

- the Vaals Formation, consisting of alternating Campanian clays, glauconiferous sands and silts;

- the Aachen Formation, consisting of Santonian glauconiferous sands and silts.

In Belgium, the Houthem Formation is sometimes not included in the Chalk Group because it is not a Cretaceous formation. Some stratigraphers therefore prefer to put it in the lower Paleogene Hesbaye Group.

The English Channel

The Channel Tunnel linking England and France was constructed by tunnelling through the West Melbury Marly Chalk (formerly the 'Chalk Marl' - a prominent sub-unit of the Grey Chalk Subgroup).

The North Sea

The chalk is also an important petroleum reservoir in the North Sea Central Graben, mainly in Norwegian and Danish sectors and to a lesser extent in the United Kingdom Continental Shelf sector (UKCS).[5]

Across the north central and northern North Sea, the Chalk Group is a major seal unit, overlying a number of blocks of reservoir rocks and preventing their fluid contents from migrating upwards. North of the line of the Mid-North Sea - Ringkobing - Fyn structural high, the Chalk Group is still recognisable in drilled samples, but becomes increasingly muddy northwards. North of the Beryl Embayment (59°30' N 01°30'E), the Chalk Group is a series of slightly to moderately calcareous mudstones grouped under the name of the Shetland Group. With the exception of some thin sandy units in the inner Moray Firth, this sequence has neither source potential nor reservoir capacity and is not generally considered a drilling target. Its thickness and homogeneity does make it a common target for carrying out directional drilling manoeuvers.

In the Shearwater and Eastern Trough Area Project areas (around 56°30' N 02°30'E, UKCS quadrants 22,23,29 and 30), the Chalk Group can be significantly overpressured. Further south in UKCS quadrant 30 and Norwegian quadrants 1 and 2, this overpressure helps preserve porosity and enables the Chalk to be an effective reservoir.

Reservoir stratigraphy

- Chalk Unit[6] 6 - Ekofisk Formation - Danian age (major reservoir in the Ekofisk oil field and others)

- Chalk Unit 5 - Tor Formation - Maastrichtian age, (major reservoir in many fields including Joanne oil field (UKCS), Valhall oil field (NCS))

- Chalk Unit 4 - Hod Formation - Late Campanian age (mostly non reservoir)

- Chalk Unit 3 - Hod Formation - Santonian to Middle Campanian

- Chalk Unit 2 - Hod Formation - Middle Turonian to Coniacian

- Turonian shale - Early Turonian (non reservoir)

- Plenus Marl - Late Cenomanian (non reservoir)

- Chalk Unit 1 - Hidra Formation - Cenomanian (non reservoir)

Reservoir geology

The majority of Chalk reservoirs are redeposited allochthonous beds. These include debris flows and turbidite flows. Porosities can be very high when preserved from diagenesis by early hydrocarbon charge. However, when these hydrocarbons are produced, diagenesis and compaction can restart which has led to several metres of subsidence at seabed, the collapse of a number of wells, and some extremely expensive remedial work to lift the platforms and re-position them.[5]

Fossils

Fossils of the echinoid Micraster from the Chalk Group have been studied for their continuous morphogical variation throughout the record.[7] Mosasaur remains referred to "Mosasaurus" gracillis from the Turonian aged Chalk Group deposits actually are more closely allied to the Russellosaurina.[8] A single partial maxillar tooth from Cenomanian aged Chalk Group described as "Iguanodon hilli" belongs to a non-Hadrosaurid Hadrosauroid.[9]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chalk. |

References

- As discussed in Chalk Facts by C. S. Harris and Scholle et al. (1983)

- Hopson, P.M., 2005 A Stratigraphical Framework for the Upper Cretaceous Chalk of England and Scotland with Statements on the Chalk of Northern Ireland and the UK Offshore Sector, British Geological Survey Research Report RR/05/01 (downloaded from www.bgs.ac.uk)

- Ordnance Survey 1:625,000 scale Physical Map of Great Britain sheet 2

- Hack, Robert; Azzam, Rafig; Charlier, Robert; 2004: Engineering Geology for Infrastructure Planning in Europe, Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 104, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-21075-7, p. 491

- "The Chalk play of the UK Central Graben" (PDF). Department of Energy and Climate Change. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Evans, D.; et al. (2003). The Millennium Atlas of the North Sea. Millennium Atlas Co. Chapter 13, Upper Cretaceous, Chalk Group. ISBN 1-86239-119-X.

- "Changes in the chalk heart-urchin Micraster Interpreted in relation to living forms". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 242 (693): 347–437. 1959-05-28. doi:10.1098/rstb.1959.0007. ISSN 2054-0280.

- Street, Hallie P.; Caldwell, Michael W. (2014-07-29). "Reassessment of Turonian mosasaur material from the 'Middle Chalk' (England, U.K.), and the status of Mosasaurus gracilis Owen, 1849". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (5): 1072–1079. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.846263. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Dalla Vecchia FM. (2009b) European hadrosauroids. Actas de las IV Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno. Salas de los Infantes, Burgos, 45–74.

Further reading

- Hancock, J.M. (1975). The Petrology of the Chalk. London: Proceedings of the Geologists Association, vol 86. pp. 449–535.

- Harris, C.S. (2007). "Chalk Facts – website on everything Chalk".

- Lousley, J.E. (1969). Wild Flowers of Chalk and Limestone. London: Collins.

- Scholle, P.A.; Bedout, D.G.; Moore, C.H. (1983). Carbonate Depositional Environments. American Association of Petroleum Geologist Memoir 33.

- Smith, A.B.; Batten, D.J. (2002). Fossils of the Chalk (Second ed.). The Palaeontological Association.