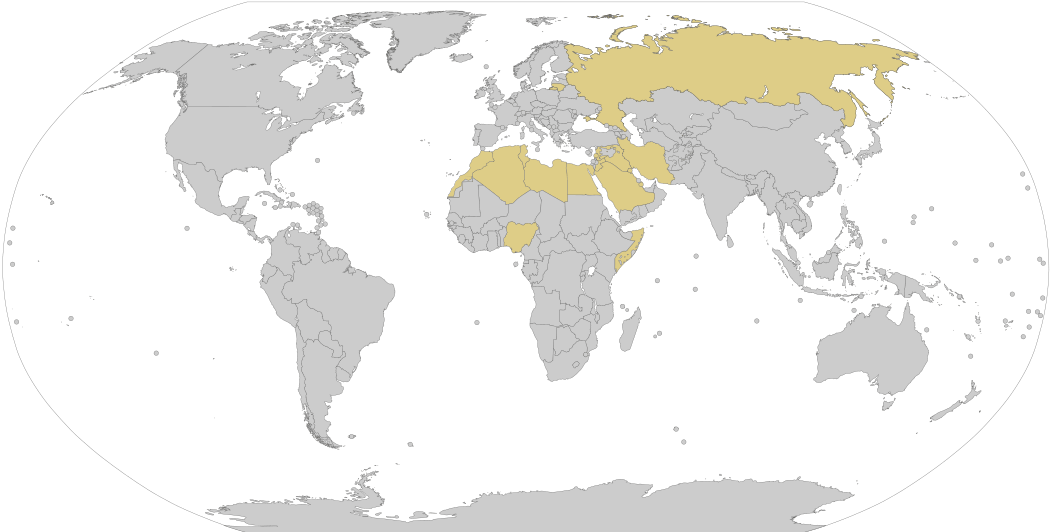

Censorship of LGBT issues

Censorship of LGBT issues is practised by a number of countries around the world. They may take a variety of forms, including "no promo homo laws" in several states of the United States,[1] the Russian ban on "promotion of non-traditional sexual relationships" and laws in Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Malaysia prohibiting advocacy that offends Islamic morality.[2]

Current laws

China

On 31 December 2015, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) of the People's Republic of China announced a new rule that banned any television show and film depicting "unnormal sexual relationships", including homosexuality.[3][4] As a result of this new rule, many popular web television series at the time like Addicted and Go Princess Go were immediately pulled from broadcasting. Online streaming services including LETV and Tencent Video followed the new rule by deleting or censoring web series with LGBT characters.[5]

In 2017, an LGBT conference was scheduled to be held in Xi'an. Western reports, using the organisers blog as their source, claimed the police had detained the organisers and threatened them.[6][7][8]

In March 2018, Oscar-winning drama "Call Me By Your Name" has been pulled from the Beijing International Film Festival's lineup.[9] It was widely speculated that the organizer of this festival was under political pressure to not show the film.

On April 14, 2018, Sina Weibo, the equivalent of Twitter in China, announced a crackdown on LGBT content, as pursuant to the China Internet Security Law and other government regulations.[10]

In May 2018, the European Broadcasting Union blocked Mango TV, one of China's most watched channels, from airing the final of the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 after it edited out Irish singer Ryan O'Shaughnessy's performance, which depicted two male dancers, and blacked out rainbow flags during Switzerland's performance.[11]

Days before the International Day Against Homophobia in 2018, two women wearing rainbow badges were attacked and beaten by security guards in Beijing. The security company dismissed the three guards involved shortly thereafter.[12]

Mr. Gay China, a beauty pageant, was held in 2016 without incident.[13] In 2018, the event host passively cancelled their engagement by not responding to any communications. Mr Gay World 2019 announced the cancellation of the Hong Kong event after communication began to deteriorate in early August. No official censorship notice was issued but some articles blamed the Chinese Government for the cancellation.[14] That same year, a woman who wrote a gay-themed novel was sentenced to 10 years and 6 months in prison for "breaking obscenity laws".[15]

Russia

In Russia, the Law for the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating for a Denial of Traditional Family Values was unanimously approved by the State Duma on 11 June 2013 (with just one MP abstaining—Ilya Ponomarev),[16] and was signed into law by President Vladimir Putin on 30 June 2013.[17]

The Russian government's stated purpose for the law is to protect children from being exposed to homosexuality—content presenting homosexuality as being a norm in society—under the argument that it contradicts traditional family values. The statute amended the country's child protection law and the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses, to make the distribution of "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships" among minors, an offence punishable by fines. This definition includes materials that "raises interest in" such relationships; cause minors to "form non-traditional sexual predispositions"; or "[present] distorted ideas about the equal social value of traditional and non-traditional sexual relationships." Businesses and organisations can also be forced to temporarily cease operations if convicted under the law, and foreigners may be arrested and detained for up to 15 days then deported, or fined up to 5,000 rubles and deported.

The Kremlin's backing of the law appealed to the Russian nationalist far-right, but gained broad support among the Russian people and the Russian Orthodox Church, as 50% of Russians are Russian-Orthodox. The law was condemned by the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe (of which Russia is a member), by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and by human rights groups, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The statute was criticised for its broad and ambiguous wording (including the broadly worded "raises interest in" and "among minors"), which critics described as an effective ban on publicly promoting the rights and culture of the LGBT community. The law was also condemned for leading to an increase in, and justification of, homophobic violence,[18] while the implications of the law in relation to the then-upcoming Winter Olympics being hosted by Sochi were also cause for concern, as the Olympic Charter contains language explicitly barring various forms of discrimination.

United States (sub-national)

Several U.S. states have "no promo homo laws", which prohibit or limit the mention or discussion of homosexuality and transgender identity in public schools. In theory, these laws mainly apply to sex education courses, but they can also be applied to other parts of the school curriculum as well as to extracurricular activities and groups such as gay-straight alliances.[19]

These explicit anti-LGBT curriculum laws can be found in 6 US states namely Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas.[20]

They are similar to the now-repealed section 28 of the British Local Government Act 1988, which prohibited local authorities from "intentionally promoting homosexuality, publishing material with the intention of promoting homosexuality, or promoting the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship."[21]

States that have repealed their "no homo promo" laws include Arizona (since 1 July 2019),[22][23] North Carolina (since 2006)[24] and Utah (since 1 July 2017).[25]

Repealed laws

Australia (sub-national)

In December 1989 in the state of Western Australia, the Parliament of Western Australia passed the Law Reform (Decriminalisation of Sodomy) Act 1989 which decriminalised private gay sex while making it a crime for a person to "...promote or encourage homosexual behaviour as part of the teaching in any primary or secondary educational institutions..." or make public policy with respect to the undefined promotion of homosexual behaviour.[26][27] It was repealed in 2002 via the Acts Amendment (Gay and Lesbian Law Reform) Act 2002, which also repealed the laws with respect to promotion of homosexual behaviour in public policy and in educational institutions.[28]

Romania

"Article 200" (Articolul 200 in Romanian) was a section of the Penal Code of Romania that criminalised homosexual relationships. It was introduced in 1968, under the communist regime, during the rule of Nicolae Ceauşescu, and remained in force until it was repealed by the Năstase government on 22 June 2001. Under pressure from the Council of Europe, it had been amended on 14 November 1996, when homosexual sex in private between two consenting adults was decriminalised. However, the amended Article 200 continued to criminalise same-sex relationships if they were displayed publicly or caused a "public scandal". It also continued to ban the promotion of homosexual activities, as well as the formation of gay-centred organisations (including LGBT rights organisations).

South Korea

In 2001, South Korea's Ministry of Information and Communication's Information and Communications Ethics Committee began censoring online LGBT content, but it stopped the practice in 2003.[29]

United Kingdom

"Section 28" or "Clause 28"[note 2] of the Local Government Act 1988 caused the addition of "Section 2A" to the Local Government Act 1986,[30] which affected England, Wales and Scotland. The amendment was enacted on 24 May 1988, and stated that a local authority "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship".[31]

The law's existence caused many groups to close or limit their activities or self-censor. For example, a number of lesbian, gay and bisexual student support groups in schools and colleges across Britain were closed owing to fears by council legal staff that they could breach the act.[32]

It was repealed on 21 June 2000 in Scotland by the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc. (Scotland) Act 2000, one of the first pieces of legislation enacted by the new Scottish Parliament, and on 18 November 2003 in the rest of the United Kingdom by section 122 of the Local Government Act 2003.[33]

Notes

- In the Russian law "for the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating for a Denial of Traditional Family Values", foreigners may be arrested and detained for up to 15 days then deported, or fined up to 5,000 rubles and deported.

- While going through the UK Parliament, the amendment was constantly relabelled with a variety of clause numbers as other amendments were added to or deleted from the Bill, but by the final version of the Bill, which received Royal Assent, it had become Section 28. Section 28 is sometimes referred to as Clause 28 – in the United Kingdom, Acts of Parliament have sections, whereas in a Bill (which is put before Parliament to pass) those sections are called clauses."When gay became a four-letter word". BBC. 20 January 2000. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

References

- Brammer, John Paul (10 February 2018). "'No promo homo' laws affect millions of students across U.S." NBC News. NBC Universal. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Rehman, Javaid; Polymenopoulou, Eleni (10 October 2012). "Is Green a Part of the Rainbow? Sharia, Homosexuality and LGBT Rights in the Muslim World". Fordham International Law Journal. Social Science Research Network. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- 网易. "新规:电视剧不得出现同性恋婚外情等内容_网易科技". tech.163.com. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "China bans same-sex romance from TV screens". CNN. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- 1994. "《太子妃升职记》有伤风化遭封杀 多部网剧被下线--传媒--人民网". media.people.com.cn. Retrieved 14 April 2018.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "2017 Human Rights Report: China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau)". U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018.

Xi’an police detained nine members of the gay advocacy group Speak Out hours before the conference it was hosting was slated to start.

- "China police detain gay activists after Xian event canceled". Reuters. 31 May 2017.

- ""Xi'an does not welcome homosexuality": 2017 Xi'an Conference changed from indefinite extension to official cancellation". SpeakOut. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019.

你若要问我,是什么样的权力可以这样代表西安“不欢迎同性恋”的活动,是什么样的人在“阻挠”。我也只能耸耸肩,我也不知道,因为同样没有人告诉我。“被取消”的理由是什么,就是“没理由”。

- "Gay Drama 'Call Me By Your Name' Pulled From Beijing Film Festival". TheWrap. 26 March 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "新浪微博宣布封杀同性恋题材内容,腐、基、耽美将被清查". www.sohu.com. 13 April 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Chinese broadcaster loses Eurovision rights over LGBT censorship, The Guardian, 11 May 2018

- China's LGBT community finds trouble, hope at end of rainbow, AFP, 2 June 2018, Archived 17 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Winsor, Ben (9 August 2016). "China crowned its first ever Mr Gay".

- "Mr Gay World cancels Hong Kong event citing concerns over LGBTQ crackdown in mainland". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "Woman Receives 10-Year Prison Sentence in China For Writing Boys-Love Novels". Anime News Network. 23 November 2018.

- "Russian 'Anti-Gay' Bill Passes With Overwhelming Majority". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "Russia passes anti-gay-law". The Guardian. Associated Press. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Paul Gallagher and Vanessa Thorpe (2 February 2014). "Shocking footage of anti-gay groups". Independent.ie. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ""No Promo Homo" Laws". GLSEN. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "#DontEraseUs: FAQ About Anti-LGBT Curriculum Laws". Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Allen, Samantha (15 May 2018). "What Did You Learn at School Today? Homophobia". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/54leg/1R/adopted/H.1346FloorSHOPE_Merged.pdf

- "Arizona SB1346 | 2019 | Fifty-fourth Legislature 1st Regular". LegiScan.

- Cooley, Amanda; Harmon (2015). "Constitutional Representations of the Family in Public Schools: Ensuring Equal Protection for All Students Regardless of Parental Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity" (PDF). Ohio State Law Journal. 76 (5): 1023.

- Winslow, Ben (20 March 2017). "Utah governor repeals law forbidding 'promotion' of homosexuality in schools". FOX 13. Salt Lake City.

- Law Reform (Decriminalisation of Sodomy) Act 1989

- Gay Law Reform in Australian States and territories

- Acts Amendment (Gay and Lesbian Law Reform) Act 2002 full text

- "Internet Censorship in South Korea". Information Policy.

- Section 28 Archived 8 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Gay and Lesbian Humanist. Created 2000-05-07, Last updated Sunday, 12 February 2006. Accessed 1 July 2006.

- Local Government Act 1988 (c. 9), section 28. Accessed 1 July 2006 on opsi.gov.uk.

- "Knitting Circle 1989 Section 28 gleanings". Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. on the site of South Bank University. Accessed 1 July 2006.

- "Local Government Act 2003". UK Government. Retrieved 30 May 2015.