Sanitization (classified information)

Sanitization is the process of removing sensitive information from a document or other message (or sometimes encrypting it), so that the document may be distributed to a broader audience. When the intent is secrecy protection, such as in dealing with classified information, sanitization attempts to reduce the document's classification level, possibly yielding an unclassified document. When the intent is privacy protection, it is often called data anonymization. Originally, the term sanitization was applied to printed documents; it has since been extended to apply to computer media and the problem of data remanence as well.

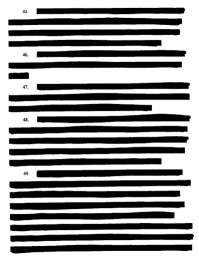

Redaction in its sanitization sense (as distinguished from its other editing sense) is the blacking out or deletion of text in a document, or the result of such an effort. It is intended to allow the selective disclosure of information in a document while keeping other parts of the document secret. Typically the result is a document that is suitable for publication or for dissemination to others than the intended audience of the original document. For example, when a document is subpoenaed in a court case, information not specifically relevant to the case at hand is often redacted.

Government secrecy

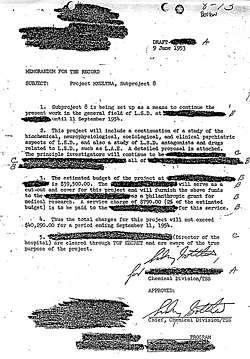

In the context of government documents, redaction (also called sanitization) generally refers more specifically to the process of removing sensitive or classified information from a document prior to its publication, during declassification.

Secure document redaction techniques

The traditional technique of redacting confidential material from a paper document before its public release involves overwriting portions of text with a wide black pen, followed by photocopying the result—the obscured text may be recoverable from the original. Alternatively opaque "cover up tape" or "redaction tape", opaque, removable adhesive tape in various widths, may be applied before photocopying.

This is a simple process with only minor security risks. For example, if the black pen or tape is not wide enough, careful examination of the resulting photocopy may still reveal partial information about the text, such as the difference between short and tall letters. The exact length of the removed text also remains recognizable, which may help in guessing plausible wordings for shorter redacted sections. Where computer-generated proportional fonts were used, even more information can leak out of the redacted section in the form of the exact position of nearby visible characters.

The UK National Archives published a document, Redaction Toolkit, Guidelines for the Editing of Exempt Information from Documents Prior to Release, "to provide guidance on the editing of exempt material from information held by public bodies."

Secure redacting is a far more complicated problem with computer files. Word processing formats may save a revision history of the edited text that still contains the redacted text. In some file formats, unused portions of memory are saved that may still contain fragments of previous versions of the text. Where text is redacted, in Portable Document Format (PDF) or word processor formats, by overlaying graphical elements (usually black rectangles) over text, the original text remains in the file and can be uncovered by simply deleting the overlaying graphics. Effective redaction of electronic documents requires the removal of all relevant text or image data from the document file. This either requires a very detailed understanding of the internal operation of the document processing software and file formats used, which most computer users lack, or software tools designed for sanitizing electronic documents (see external links below).

Redaction usually requires a marking of the redacted area with the reason that the content is being restricted. US government documents being released under the Freedom of Information Act are marked with exemption codes that denote the reason why the content has been withheld.

The US National Security Agency (NSA) published a guidance document which provides instructions for redacting PDF files.[1]

Printed matter

Printed documents which contain classified or sensitive information frequently contain a great deal of information which is less sensitive. There may be a need to release the less sensitive portions to uncleared personnel. The printed document will consequently be sanitized to obscure or remove the sensitive information. Maps have also been redacted for the same reason, with highly sensitive areas covered with a slip of white paper.

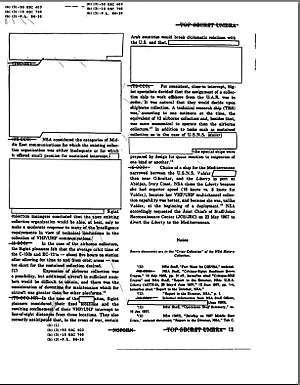

In some cases, sanitizing a classified document removes enough information to reduce the classification from a higher level to a lower one. For example, raw intelligence reports may contain highly classified information such as the identities of spies, that is removed before the reports are distributed outside the intelligence agency: the initial report may be classified as Top Secret while the sanitized report may be classified as Secret.

In other cases, like the NSA report on the USS Liberty incident (right), the report may be sanitized to remove all sensitive data, so that the report may be released to the general public.

As is seen in the USS Liberty report, paper documents are generally sanitized by covering the classified and sensitive portions and then photocopying the document, resulting in a sanitized document suitable for distribution.

Computer media and files

Computer (electronic or digital) documents are more difficult to sanitize. In many cases, when information in an information system is modified or erased, some or all of the data remains in storage. This may be an accident of design, where the underlying storage mechanism (disk, RAM, etc.) still allows information to be read, despite its nominal erasure. The general term for this problem is data remanence. In some contexts (notably the US NSA, DoD, and related organizations), sanitization typically refers to countering the data remanence problem; redaction is used in the sense of this article.

However, the retention may be a deliberate feature, in the form of an undo buffer, revision history, "trash can", backups, or the like. For example, word processing programs like Microsoft Word will sometimes be used to edit out the sensitive information. Unfortunately, these products do not always show the user all of the information stored in a file, so it is possible that a file may still contain sensitive information. In other cases, inexperienced users use ineffective methods which fail to sanitize the document. Metadata removal tools are designed to effectively sanitize documents by removing potentially sensitive information.

In May 2005 the US military published a report on the death of Nicola Calipari, an Italian secret agent, at a US military checkpoint in Iraq. The published version of the report was in PDF format, and had been incorrectly redacted using commercial software tools. Shortly thereafter, readers discovered that the blocked-out portions could be retrieved by copying them and pasting into a word processor.[2]

Similarly, on May 24, 2006, lawyers for the communications service provider AT&T filed a legal brief[3] regarding their cooperation with domestic wiretapping by the NSA. Text on pages 12 to 14 of the PDF document were incorrectly redacted, and the covered text could be retrieved using cut and paste.[4]

At the end of 2005, the NSA released a report giving recommendations on how to safely sanitize a Microsoft Word document.[5]

Issues such as these make it difficult to reliably implement multilevel security systems, in which computer users of differing security clearances may share documents. The Challenge of Multilevel Security gives an example of a sanitization failure caused by unexpected behavior in Microsoft Word's change tracking feature.[6]

The two most common mistakes for incorrectly redacting a document are adding an image layer over the sensitive text without removing the underlying text, and setting the background color to match the text color. In both of these cases, the redacted material still exists in the document underneath the visible appearance and is subject to searching and even simple copy and paste extraction. Proper redaction tools and procedures must be used to permanently remove the sensitive information. This is often accomplished in a multi-user workflow where one group of people mark sections of the document as proposals to be redacted, another group verifies the redaction proposals are correct, and a final group operates the redaction tool to permanently remove the proposed items.

References

- "Redaction of PDF Files Using Adobe Acrobat Professional X" (PDF). Security Configuration Guide. National Security Agency Information Assurance Directorate.

- BBC Report (May 2, 2005). "Readers 'declassify' US document". BBC.

- Declan McCullagh (May 26, 2006). "AT&T leaks sensitive info in NSA suit". CNet News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- NSA SNAC (December 13, 2005). "Redacting with Confidence: How to Safely Publish Sanitized Reports Converted From Word to PDF" (PDF). Report# I333-015R-2005. Information Assurance Directorate, National Security Agency, via Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2006-05-29. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rick Smith (2003). The Challenge of Multilevel Security (PDF). Black Hat Federal Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-06.