Bowing in Japan

Bowing in Japan (お辞儀, Ojigi) is the act of lowering one's head or the upper part of the torso, commonly used as a sign of salutation, reverence, apology or gratitude in social or religious situations.[1]

.jpg)

Historically, ojigi was closely affiliated with the samurai. The rise of the warrior class in the Kamakura period (1185–1333) led to the formations of many well-disciplined manuals on warrior etiquette, which contained instructions on proper ways to bow for the samurai.[2] The Japanese word お辞儀 (ojigi) was derived from the homophone お時宜, which originally meant "the opportune timing to do something". It did not start to specifically denote the act of bowing in the contemporary sense until late Edo period (1603–1868), when samurai bowing etiquette had spread to the common populace.[2][3] Nowadays, the ojigi customs based on the doctrines of the Ogasawara School of warrior etiquette—which was founded some 800 years ago—is the most prevalent in society.[2]

In modern-day Japan, bowing is a fundamental part of social etiquette which is both derivative and representative of Japanese culture, emphasizing respect and social ranks. From everyday greetings to business meetings to funerals, ojigi is ubiquitous in Japanese society and the ability to bow correctly and elegantly is widely considered to be one of the defining qualities of adulthood.[4] Therefore, even though most Japanese people start bowing at a very young age, many companies in Japan will take the extra effort to specially train their employees on how to bow in business meetings.[5][6]

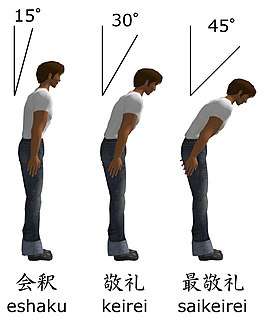

Generally speaking, ojigi in Japan can be coarsely divided into two categories: zarei (座礼), bowing while kneeling, and ritsurei (立礼), bowing while standing. In either case, it is considered essential to bend one's body only at the waist and keep one's back completely straight during the bowing gesture. Failure to do so is often thought of as an indication of lethargy, insincerity and even disrespect. Different sub-categories of ojigi vary mainly in the angles of inclination of one's body and the positions of one's hands, which are determined both by the status of the person one is bowing to and the scenario or context of gesture.[4]

History

While there are few official records on how the etiquette of bowing originated in Japan, it is widely believed that it traces its roots back to the propagation of Buddhism to Japan from the kingdoms of ancient China between the 5th and 8th centuries.[7] In Buddhist teachings, bowing is an important gesture of piety and respect. Worshipers bow to Buddha statues in devotion, and disciples bow to their masters in admiration. Such religious etiquette was often believed to be the foundation of ojigi in Japan.[8]

In the Kamakura period (1185–1333), with the appearance of the first feudal military government, the warrior class, or samurai, started playing a more prominent role in Japanese history. The principles and concepts of the warrior class began to shape the cultural standards of the society. Ojigi, along with other forms of samurai etiquette, under the influence of Zen Buddhism, became much more disciplined and widely practiced among the warrior class.[9]

In the subsequent Muromachi period (1336–1573), systematically written manuals on different sects of samurai etiquette, such as the Ise School (伊勢流, Ise-Ryū) and Ogasawara School (小笠原流, Ogasawara-Ryū), were developed to strengthen and promote the cultural identity of the warrior class. These were often considered the first blueprints on proper ways to dress and behave for the samurai. The art of bowing, consequently, also became increasingly complicated and well-established. Different variations of ojigi were to be used for different scenarios, from indoor meetings, to archery matches, to praying at sacred temples. However, the advancement of warrior etiquette came to a halt in the later years of the Muromachi period, which was characterized by social turmoil and unrelenting warfare, popularly known as the Sengoku Era (Age of Warring States; 1467–1600). Formal etiquette was largely abandoned in the times of chaos and cruelty, and customs of ojigi faded in the course of history for over a century.[10][11]

The establishment of the third and final feudal military government in the Edo period (1603–1868) brought peace and prosperity back to the islands, resulting in the second blooming of samurai etiquette in Japan. Classic customs of the Ogasawara School were revitalized and new schools of disciplines, such as the Kira School (吉良流, Kira-Ryū), mushroomed. In the meantime, stability and burgeoning urban sectors provided common Japanese people with the opportunity for recreation and education. Since the warrior class was put at the top of the social ladder in the new social ranking system under the governance of the Tokugawa Shogunate, warrior etiquette like ojigi became ever more popular and gradually spread to the common people. As a by-product of the strict divisions of social classes (身分制, Mibunsei), the showcasing of social status also became progressively important in ojigi, a trait that is still observable in Japan to this day.[2][11] Moreover, proliferation in arts gave birth to many cultural treasures, such as the tea ceremony, which gradually became a byword for refinement in the Edo period. Schools for tea ceremony then acted as another important source for promoting social etiquette to the commoners in Japan, such as zarei (bowing while kneeling).[12][13]

In the business world

Customs and manners in Japanese business are reputed to be some of the most complicated and daunting in the world, especially to a foreign person who is not familiar with the Japanese ideology of ranks and traditions.[5][6] Failure to perform the right type of ojigi for the other person's status is considered a workplace faux pas or even an offense. Especially more traditional and conservative Japanese people view ojigi as a representation of the Japanese identity and find beauty in the performance of a perfect ojigi with the correct posture. Therefore, many industries in Japan will offer new recruits extensive training on correct ways to perform ojigi and other important business etiquette.[5]

Eshaku, keirei and saikeirei are the three typical categories of ojigi practiced in the business world in Japan. No matter which type is chosen, it is important to pay constant attention to one's muscles and posture. In particular, one's back should be kept straight and the body below the waist should stay still and vertical throughout the bowing gesture. Slouching backs and protruding hips are both considered ugly and unprofessional behaviors.[4] Another important technique for ojigi is the synchronization of one's movements with one's breathing, commonly referred to as Rei-sansoku (礼三息) in Japanese. To elaborate, the lowering movement of one's upper body should take as long as the inhalation of one's natural breath. Next, one should stay completely still at the bowing position when exhaling, before returning to one's original stance during the inhalation of the second breath. Rei-sansoku ensures the harmonic balance between one's movements so that the ojigi feels neither rushed nor protracted.[4]

Eshaku

Eshaku (会釈) is generally performed with a slight inclination of about 15° of one's upper torso. At the bowing position, one's eyes should glance at the floor roughly three meters in front of one's feet. It is a very casual form of greeting in business, usually performed between colleagues with the same status, or when more formal gestures are deemed unnecessary, like when one casually bumps into someone on the street.

Keirei

The second type, keirei (敬礼), is the most commonly used variation of ojigi in Japanese business. It gives a more formal and respectful impression than eshaku, but less than saikeirei, the final type of ojigi. Conventionally, keirei is performed with an inclination of about 30° of the upper body. At the bowing position, one's gaze should rest on the floor approximately 1 meter in front of his feet. Possible scenarios for its usage include greeting clients, entering a meeting and thanking superiors at work.

Saikeirei

Finally, saikeirei (最敬礼), which literally means "the most respectful gesture", is, as the name suggests, the ojigi that shows the uttermost respect towards the other party. It is mostly used when greeting very important personnel, apologizing or asking for big favors. Saikeirei is characterized by an even deeper inclination of one's upper body than keirei, typically somewhere from 45° to 70°. Additionally, as saikeirei is only used in grave situations, one is expected to stay still at the bowing position for a relatively long time to show one's respect and sincerity.[7][14][15]

In terms of hand positions, men should keep them naturally at both sides of their legs, whereas women often place one hand on top of the other in the center somewhere below their abdomen.[16]

Zarei

.jpg)

Zarei is a bowing etiquette unique to East Asia, which involves bending one's upper body at kneeling, or seiza, position on traditional Japanese style tatami floors. With the Westernization of indoor decoration and lifestyles, zarei is becoming less and less commonly practiced in the daily lives of Japanese people. Some Japanese people even find zarei an excruciating ordeal to their knees and waists.[17] Nevertheless, zarei remains an important part of Japanese culture, especially in more traditional activities such as the tea ceremony, kendo, and Japanese dancing (日本舞踊, Nihon-buyō).[17]

_(14596103440).jpg)

As with standing bows, zarei, as well as many other domains of Japanese culture like ikebana and garden design, can be classified into three main styles based on the doctrines of Japanese calligraphy: shin (真), the most formal style, gyō (行) the intermediate style, and sō (草), the most casual style.[18][19]

Saikeirei (zarei version)

Saikeirei (the shin style) is the most formal and reverent of the three types. Starting from seiza position, the person is expected to lower his upper body all the way until his chest presses against his lap. In the process, his hands should slide forward along his thighs until they are on the floor roughly 7 cm away from his knees. In the final position, his face should be about 5 cm away from the floor. His palms should lie flat on the floor, forming a triangle directly under his face with the tips of the index fingers lightly touching one another. For saikeirei, like the standing version, it is important to allow an adequate amount of time in the bowing position before returning to the original seiza posture, in order to show the uttermost sincerity and respect. The entire procedure should take roughly 10 seconds to complete.

Futsūrei

Futsūrei (普通礼, the gyō style) is the most commonly used variation of zarei in formal situations and most traditional activities. To perform a futsūrei, one should lower one's upper body until one's face is roughly 30 cm away from the floor. In the meantime, one's hands should move in a similar fashion as saikeirei, again forming a triangle directly under one's face in the final bowing position.

Senrei

Senrei (浅礼, the sō style) is the most casual type of zarei in everyday life, used mainly as greetings in informal situations. It is characterized by a relatively slight inclination (roughly 30°) of the upper torso. During the lowering movement, one's hands should slide naturally along one's thighs to the knees. In the bowing position, unlike the other two types, only one's fingertips should touch the floor. Men generally keep their hands in front of each knee, while women place their hands together in the center.[20][21][22]

In various activities

Kendo

.jpg)

Kendo, like many other forms of martial arts in Japan, takes great pride in its samurai traditions. The kendo saying "Begins with etiquette and ends with etiquette" (礼に始まり、礼に終わる, Rei ni Hajimari, Rei ni Owaru) helps to illustrate the importance of civility and sportsmanship in its practice. Ojigi is especially an essential cog in its etiquette system, such that a kendo practitioner can bow as many as eighty times during a tournament or practice.[22][23]

First of all, kendo practitioners bow to the dojo whenever they enter and leave the building, as it is considered a sacred space in martial arts practice. Upon arrival, the disciples will bow to their teachers and seniors as greetings, starting with the highest-ranking member. At the beginning and end of a match, opponents will bow to each other as a sign of mutual respect and humility. Before each training session, a player will bow first to the shōmen (正面, the direction of the Shinto altar or the most important person), then bow to his teachers and finally to his practice partner. In a tournament, the players of the first and last match usually bow to the referees before bowing to each other. Conventionally, a formal ojigi such as keirei or saikeirei is necessary when addressing people of higher positions, while a more casual bow of about 15° is typical between the opponents.[22][23] When zarei is required, the players have to first kneel down into seiza position (着座, Chakuza). In kendo practice, it is customary for the players to kneel down by bending their left legs first and getting up with their right legs first, commonly known as sazauki (左座右起) in Japanese. It is said to serve the purpose from former times of making sure one can always draw the katana out as quickly as possible in case of emergencies, since the katana is usually carried on the left side of the body. For a similar reason, the right hand should lag slightly behind the left hand in reaching their final positions on the floor.[23]

Shinto shrine visits

Like the religion itself, the etiquette of praying in Shintoism has gone through dramatic changes over the centuries. In modern-day Japan, worshipers at a Shinto shrine generally follow the so-called 2 bows, 2 claps, and 1 bow procedure (二拝二拍手一拝).

First of all, upon arrival at the shrine, it is proper for worshipers to perform a slight eshaku towards the main temple building as they cross the torii, which is believed to be the sacred gateway between the mundane world and the realm of the gods. The same procedure applies when they are leaving the temple complex.[24]

When they approach the main temple building, it is considered respectful to perform another eshaku towards the altar as an introduction. Next, most worshipers will throw some Japanese coins into the offertory box (賽銭箱, Saisen-bako) and ring the bell above the entrance for blessings. In the main praying process, worshipers should first perform two deep bows of up to 90° to pay tribute to the Shinto kami, followed by loudly clapping twice in front of the chest. Same as the noise made by the coins and the bell, the loud claps are believed to have the effect of exorcising negative energy or evil spirits. Finally, after making wishes to the kami with both palms held together in the clapping position, the worshiper should put the hands down and perform another deep bow to finish the praying ceremony.[14][24]

Funerals

In a traditional Buddhist funeral in Japan, it is customary for the guests to mourn the deceased by burning powdered incense (お焼香, O-shōkō), once during the wake (通夜, Tsuya) and later again during the farewell ceremony (告別式, Kokubetsu-shiki). Although different variations of the ritual exist, the version involving ritsurei (standing bows) is the most prevalent in modern society.[25][26]

First of all, immediate relatives of the deceased will perform a formal bow to the Buddhist monks, who are hired to chant the religious sutra, and all the other guests to thank them for their attendance. Then, they will one by one walk up to the incense burning station (焼香台, Shōkō-dai) near the coffin to pay respect and bid farewell to the deceased. Ordinary guests will either follow them or, in other cases, line up to visit a separate incense burning station slightly further away. All mourners should perform a deep bow to the portrait of the deceased with their palms held together in the Buddhist fashion. Next, they should pinch some powdered incense (抹香, Makkō) from the container with their right hands, raise it up to their foreheads and humbly drop it into the incense burners. Such process can be repeated up to three times depending on the religious customs of the region. Last but not least, it is also essential that the ordinary guests bow to the mourning family before and after the incense burning procedure to show their condolences.[26][27]

The tea ceremony

The tea ceremony (茶道, Sadō) is a traditional art form in Japan featuring the ritualistic preparation and consumption of powdered green tea along with matching Japanese desserts. Every single element of the experience, from the calligraphy on the walls to the decorations of the utensils, is carefully tailored according to the aesthetic concepts of the host to match the season and theme of the gathering. Therefore, it is important for the guests to show their gratitude for the host's hard work by behaving in a humble and respectful manner.[28]

When to bow

A regular tea ceremony usually consists of less than five guests, whose ranks, sitting positions and duties during the ceremony will be decided beforehand. A guest of honor (主客, Shukyaku) will be chosen, who will always be the first one served and engage in most of the ceremonial conversations with the host (亭主, Teishu).

Before going into the tea room, each guest should individually perform a formal bow to the space itself in respect to its profound spirituality. Upon entering, prior to the official start of the ceremony, the guests can take their time to admire the ornaments in the tokonoma and the utensils of the tea preparation station (点前座, Temae-za), which are all carefully selected to match the theme of the event. It is utterly important for the guests to show their appreciation of the host's effort by bowing to each piece of artwork before and after the admiration process.[29] Then, formal bows will be performed by everyone in the room including the host to mark the beginning of the ceremony and later again at the start of the tea preparation procedure. When each course of dessert or tea is served, the host will bow to the guest of honor to indicate that it is ready for the guests to consume, and the guest of honor will bow in response as a form of gratitude. Moreover, it is customary for each guest to bow to the person behind as apology for consuming first. At the end of the ceremony, another round of bows will be exchanged between the guests and hosts to thank each other for the experience. The guest of honor will also bow to all the other guests to thank them for letting him sit in the most honorable position, while the other guests will return the bow to thank the guest of honor for the delivery of the interesting conversation with the host.[30]

How to bow

Ojigi in Japanese tea ceremony is mainly done in the zarei fashion, which can be similarly classified into three types based on the degree of formality of the gesture: shin, gyō, and sō (真行草). Although largely derivative from the samurai etiquette of the Edo period, contemporary zarei in tea ceremony is somewhat different from the aforementioned samurai version. In modern society, it is equally likely to see an ordinary Japanese person perform the zarei etiquette in either of these two variations.

The formal shin-style zarei is characterized by a 45° inclination of the upper body. In the bowing position, both hands should be fully rested on the floor in a triangle pattern with the tips of the index fingers touching each other. The semi-formal gyō-style zarei involves a 30° inclination of the upper body. Unlike the samurai version, just the parts of the fingers beyond the second knuckles should touch the floor in the bowing position. Finally, the casual sō-style zarei features a shallow 15° inclination of the upper body with only the fingertips contacting the floor. Details of the etiquette may vary depending on which school of tea ceremony one subscribes to, so it is always a good idea to check the manners of the host and the guest of honor for guidelines of proper decorum.

Additionally, in a tea ceremony, guests often bring with them a traditional Japanese fan (お扇子, O-sensu), which they will place horizontally on the floor in front of them before performing the formal and semi-formal zarei gestures.[29][30]

See also

References

- Bow, (n.d.) In Oxford English Dictionary Online Website, Retrieved 01 May 2019.

- "日本人の所作・礼儀作法の歴史 (Japanese Conduct ∙ The History of Etiquettes)". SAMURAI've. March 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- お辞儀 (Ojigi), (n.d.), In 語源由来辞典 (Japanese Etymology Online Dictionary), Retrieved 03 May 2019.

- Ogasawara, K. (January 2017). 日本人の9割が知らない日本の作法 (The Japanese Etiquette 90% of Japanese People Don't Know). Tokyo: Seishun Publishing Co. ISBN 978-4413096607.

- De Mente, B. L. (2017). pp. 65–69.

- Barton, D. W. (May 2018). "Bowing In Japan – A Basic Formality". Japanology. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "How to Bow – Bowing Culture in Japan". Japan Live Perfect Guide. December 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Buswell, R. E. Jr. (2004). Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. USA: Macmillan Reference. pp. 265–266. ISBN 0-02-865718-7.

- Stalker, N. K. (2018). pp. 79–110.

- Stalker, N. K. (2018). pp. 112 – 142.

- Kanzaki, N. (2016). 「おじぎ」の日本文化 (Japanese Culture of "Bowing"). Tokyo: Kadokawa. ISBN 978-4044000080.

- Stalker, N. K. (2018). pp. 144 – 179.

- De Mente, B. L. (2017). pp. 52–54.

- Miller, Vincent (2018). Japanese Etiquette : the Complete Guide to Japanese Traditions, Customs, and Etiquette. Leipzig: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-72293-827-7. OCLC 1053809052.

- Ogasawara, K. (n.d.). "Bowing. The Best-Known Form of Japanese Etiquette". Manabi Japan. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Akahige, Kami (2015). Japan Etiquette: Learn Japanese Manners with Simple Tip Sheets. ASIN B0187UXG2I.

- Giga, Michiko (2012). "古くから伝わる日本の作法: 現代日常生活への適応 ⎯ (Time-honoured Japanese Etiquette: Adapted to Modern Everyday Life)". 鈴鹿国際大学紀要 : campana / 鈴鹿国際大学. 19: 135–145.

- Stalker, N. K., (2018), pp. 58-59.

- "Shingyoso 真行草". Classical Martial Arts Research Academy. 2015-05-04. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- Francisco, A. (October 2015). "Bowing in Japan: Everything you've ever wanted to know about how to bow, and how not to bow, in Japan". Tofugu. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "和式作法: 座 礼 (Japanese Etiquette: Zarei)". hac.cside.com. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Tokeshi, Jinichi (2003). Kendo: Elements, Rules and Philosophy. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 78–84. ISBN 0-8248-2598-5.

- Imafuji, Masahiro (2017). Kendo Guide for Beginners: A Kendo Instruction Book Written By A Japanese For Non-Japanese Speakers Who Are Enthusiastic to Learn Kendo. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 4–25. ISBN 978-1-4636-9533-0.

- "参拝の作法 (Praying Etiquette)". 東京都神社庁. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "お焼香マナー (Incense Burning Manners)". Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Japanese Funerals | JapanVisitor Japan Travel Guide". www.japanvisitor.com. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "日本のお葬式 (Japanese Funerals)" (PDF). Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Walden, Corey (2013). An Introduction To Tea Ceremony And Ritual. ASIN B00DH4T606.

- Kitami, Soukou (2019). 裏千家 茶道ハンドブック (Urasenke Tea Ceremony Handbook). 山と溪谷社. pp. 8–20. ISBN 978-4635490368.

- Oota, Tooru (2018). 茶道のきほん:「美しい作法」と「茶の湯」の楽しみ方 (Basics of Teaism: "Beautiful Etiquette" and Ways of Enjoying "Tea Ceremony"). メイツ出版. pp. 1–49. ISBN 978-4780420708.

Bibliography

- De Mente, B. L. (2017). Japan: A Guide to Traditions, Customs and Etiquette. Hong Kong: Tuttle Publishing. pp. 52–54, 65–69. ISBN 978-4-8053-1442-5.

- Stalker, N. K. (2018). Japan: History of Culture from Classic to Cool. Oakland: University of California Press. pp. 79–179. LCCN 2017058048.