Censer

A censer, incense burner, perfume burner or pastille burner is a vessel made for burning incense or perfume in some solid form. They vary greatly in size, form, and material of construction, and have been in use since ancient times throughout the world. They may consist of simple earthenware bowls or fire pots to intricately carved silver or gold vessels, small table top objects a few centimetres tall to as many as several metres high. Many designs use openwork to allow a flow of air. In many cultures, burning incense has spiritual and religious connotations, and this influences the design and decoration of the censer.

.jpg)

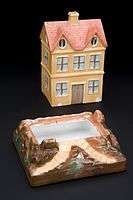

Often, especially in Western contexts, "censer" is used for pieces made for religious use, especially those on chains that are swung through the air to spread the incense smoke widely, while "perfume burner" is used for objects made for secular use. The original meaning of pastille was a small compressed mixture of aromatic plant material and charcoal that was lit to release the odour, and pastille-burners were designed for this, for use in the home. Pastilles were made at home until their heyday in the early 19th century, and the burners are often made in pottery or porcelain.[1]

Some types could also be used as pomanders, where the perfume diffuses slowly by evaporation rather than burning.[2]

Use

_01_by_shakko.jpg)

For direct-burning incense, pieces of the incense are burned by placing them directly on top of a heat source or on a hot metal plate in a censer or thurible.[3]

Indirect-burning incense, also called "non-combustible incense",[4] is a combination of aromatic ingredients that are not prepared in any particular way or encouraged into any particular form, leaving it mostly unsuitable for direct combustion. The use of this class of incense requires a separate heat source since it does not generally kindle a fire capable of burning itself and may not ignite at all under normal conditions. This incense can vary in the duration of its burning with the texture of the material. Finer ingredients tend to burn more rapidly, while coarsely ground or whole chunks may be consumed very gradually as they have less total surface area. The heat is traditionally provided by charcoal or glowing embers.

For home use of granulated incense, small, concave charcoal briquettes are sold. One lights the corner of the briquette on fire, then places it in the censer and extinguishes the flame. After the glowing sparks traverse the entire briquette, it is ready to have incense placed on it.

For direct-burning incense, the tip or end of the incense is ignited with a flame or other heat source until the incense begins to turn into ash at the burning end. Flames on the incense are then fanned or blown out, with the incense continuing to burn without a flame on its own.

Censers made for stick incense are also available; these are simply a long, thin plate of wood, metal, or ceramic, bent up and perforated at one end to hold the incense. They serve to catch the ash of the burning incense stick.

In Taoist and Buddhist temples, the inner spaces are scented with thick coiled incense, which are either hung from the ceiling or on special stands. Worshipers at the temples light and burn sticks of incense. Individual sticks of incense are then vertically placed into individual censers.

Chinese use

_-_Walters_49466.jpg)

The earliest vessels identified as censers date to the mid-fifth to late fourth centuries BCE during the Warring States period. The modern Chinese term for "censer," xianglu (香爐, "incense burner"), is a compound of xiang ("incense, aromatics") and lu (爐, "brazier; stove; furnace"). Another common term is xunlu (熏爐, "a brazier for fumigating and perfuming"). Early Chinese censer designs, often crafted as a round, single-footed stemmed basin, are believed to have derived from earlier ritual bronzes, such as the dou 豆 sacrificial chalice.

Among the most celebrated early incense burner designs is the hill censer (boshanlu 博山爐), a form that became popular during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE). Some scholars believe hill censers depict a sacred mountain, such as Mount Kunlun or Mount Penglai. These elaborate vessels were designed with apertures that made rising incense smoke appear like clouds or mist swirling around a mountain peak.[5] The Han Dynasty scholar Liu Xiang (77–6 BCE) composed an inscription describing a hill censer:

I value this perfect utensil, lofty and steep as a mountain! Its top is like Hua Shan in yet its foot is a bronze plate. It contains rare perfumes, red flames and green smoke; densely ornamented are its sides, and its summit joins azure heaven. A myriad animals are depicted on it. Ah, from it sides I can see ever further than Li Lou [who had legendary eyesight].[6]

Another popular design was the small "scenting globe" (xiangqiu 香球), a device similar to a pomander, but used for burning incense. The famed inventor and craftsmen, Ding Huan (1st c. BCE), is believed to have made these with gimbal supports so the censer could easily be used to fumigate or scent garments. This is described by Edward H. Schafer:

"Censing baskets" were globes of hollow metal, pierced with intricate floral or animal designs; within the globe, an iron cup, suspended on gimbals, contained the burning incense. They were used to perfume garments and bedclothes, and even to kill insects.[7]

Other Chinese censers are shaped like birds or animals, sometimes designed so that the incense smoke would issue from the mouth. During the medieval period when censers were more commonly used in Buddhist and Daoist rituals, hand-held censers (shoulu 手爐) fashioned with long handles were developed.

Archeologists have excavated several censers from Han era tombs that contained aromatics or ashen remains. Some of these aromatic plants have been identified as maoxiang (茅香 "Imperata cylindrica, thatch grass"), gaoliangjiang (高良薑 "Galangal"), xinyi (辛夷 "Magnolia liliiflora, Mulan magnolia), and gaoben (藁本"Ligusticum sinense, Chinese lovage"). Scholars speculate burning these grasses "may have facilitated communication with spirits" during funeral ceremonies.[8]

According to the Sinologist and historian Joseph Needham, some early Daoists adapted censers for the religious and spiritual use of cannabis. The Daoist encyclopedia Wushang Biyao (無上秘要 "Supreme Secret Essentials", ca. 570 CE), recorded adding cannabis into ritual censers.[9] The Shangqing School of Daoism provides a good example. The Shangqing scriptures were written by Yang Xi (330– c. 386 CE) during alleged visitations by Daoist "immortals", and Needham believed Yang was "aided almost certainly by cannabis".[10] Tao Hongjing (456-536 CE), who edited the official Shangqing canon, also compiled the Mingyi bielu (名醫別錄 "Supplementary Records of Famous Physicians"). It noted that mabo (麻勃 "cannabis flowers"), "are very little used in medicine, but the magician-technicians ([shujia] 術家) say that if one consumes them with ginseng it will give one preternatural knowledge of events in the future."[10] Needham concluded,

Thus all in all there is much reason for thinking that the ancient Taoists experimented systematically with hallucinogenic smokes, using techniques which arose directly out of liturgical observance. … At all events the incense-burner remained the centre of changes and transformations associated with worship, sacrifice, ascending perfume of sweet savour, fire, combustion, disintegration, transformation, vision, communication with spiritual beings, and assurances of immortality. Wai tan and nei tan met around the incense-burner. Might one not indeed think of it as their point of origin?[11]

These Waidan (外丹 "outer alchemy") and neidan (內丹 "inner alchemy") are the primary divisions of Chinese alchemy.

During the T’ang period, incense was used by upper class people for personal hygiene, romantic rendezvous, and deodorizing the interior of edifices. These included places of worship, dwellings, and work-spaces. Dating back to the seventh century AD, the kuanhuo(changing of fire) ceremony took place, where people would cleanse their homes with incense. However, in some parts of East Asia, incense burners were used as a way to tell time

In the Far East, incense was used as a way to tell time because it was a simple mechanism and generally not a fire hazard. Time increments were marked off on each incense stick to show how much time had passed, then placed in a ritual tripod vessel known as a ting. During imperial coronations, incense sticks would be used to tell how long the ceremony was. Other variations of incense is the spiral incense coil. The spiral incense coil was used to measure time for longer durations. One spiral equated to one night. This type of incense was mainly used by the five ‘night watches’ of the community. The length of their shifts and breaks were determined by the time increments marked off on the spirals.[12]

Middle East

Incense burners (miqtarah in Arabic) were used in both religious and secular contexts, but were more widely utilized in palaces and houses. The earliest known examples of dish-shaped incense burners with zoomorphic designs were excavated in Ghanza [13][14], while the earliest examples of zoomorphic incense burners are from 11th-century Tajikistan.[15] It is most likely that this practice was inspired by Hellenistic style incense burners[14] as well as the frankincense trade present in the Arabian peninsula since the 8th century BCE.[16]

A wide variety of designs were used at different times and in different areas. Pottery and stone incense burners were the most common while those made of metals were reserved for the wealthy. Artisans created these incense burners with moulds or the lost-wax method. Openwork zoomorphic incense burners with lynx or lion designs were popular in the Islamic world; bronze or brass examples are found from the 11th-century until the Mongol conquests of the 13th-century[15]. These were especially popular during the Seljuq period.[17] The extensive use of lynx shape incense burners was due to the animals popularity as a hunting animal and as pet in Muslim courts[15]. The complexity of the piece would also make it fit into a palatial setting. This style of incense burners could measure about 22 cm; others like an example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York measures 85 cm[17]. The surface of the object would be decorated with bands of Arabic calligraphy which would imitate a tiraz. This bands of text could include the name of the artist and the patron as well as prayers and good wishes for the owner. To insert coals and incense the head would be removed; the openwork geometric design would then allow the scented smoke to escape.[18] Depending on the size, the incense burner could be either carried on a tray or carried by using the tail as a handle.

In mosques, incense burners do not have a liturgical use or a specific design denoted for religious context.[19] However, they are still an important part of rituals and weddings. Other religious groups in Middle East such as the Copts do have ceremonial uses for incense burners.

Japan

Koro (Japanese: 香炉, kōro), also a Chinese term, is a Japanese censer often used in Japanese tea ceremonies.

Examples are usually of globular form with three feet, made in pottery, Imari porcelain, Kutani ware, Kakiemon, Satsuma, enamel or bronze. In Japan a similar censer called a egōro (柄香炉) is used by several Buddhist sects. The egōro is usually made of brass with a long handle and no chain. Instead of charcoal, makkō powder is poured into a depression made in a bed of ash. The makkō is lit and the incense mixture is burned on top. This method is known as Sonae-kō (Religious Burning).[20]

Mesoamerica

_01.jpg)

Used domestically and ceremonially in Mesoamerica, particularly in the large Central-Mexican city of Teotihuacan (100–600 AD) and in the many kingdoms belonging to the Maya civilization, were ceramic incense burners. The most common materials for construction were Adobe, plumbate[21], and earthenware. These materials can be dried by the sun and were locally sourced, making them the perfect material for a Mayan craftsman. Censers vary in decoration. Some are painted using a fresco style technique or decorated with adornos[22], or small ceramic ornaments. These decorations usually depicted shells, beads, butterflies, flowers, and other symbols with religious significance that could to increase rainfall, agricultural abundance, fertility, wealth, good fortune or ease the transition of souls into the underworld.[23] To identify precious materials such as jadeite and quetzal feathers, important visual markers of status[24], artists used colorful paints.

Used to communicate with the Gods, these censers functioned for acts of religious purification. Incense would be presented to the divine being. In fact, some people were appointed the position of fire priest. Fire priests dealt with most tasks related to incense burning. Some rituals involved a feast, which would be followed by the fire priest igniting a sacred brazier in the temples. It was given to the divine beings and deities as offerings on a daily basis. The practice would end at the sound of a trumpet made from a conch shell. Another function of incense was to heal the sick. Once recuperated, the diseased would present some incense to the appropriate gods to repay them for being cured.[25]Made up of copal (tree resin), rubber, pine, herbs, myrrh, and chewing gum, the incense produced what was described as "the odor of the center of heaven."[26]

The shape of incense burners in the Maya southern lowlands reflected religious and cultural changes over time. Some censers were used in funerals and funerary rituals, such as those depicting the Underworld Jaguar or the Night Sun God. When a king would die, ‘termination rituals’ were practiced. During these rituals, incensarios would be smashed and older temples were replaced with new ones.[27]Mayan censers, which had a reservoir for incense on top of a vertical shaft were highly elaborate during the Classic period (600–900 AD), particularly in the kingdom of Palenque, and usually show the head of a Mayan deity. In Post-Classic Yucatán, particularly in the capital of the kingdom of Mayapan, censers were found in great numbers, often shaped as an aged priest or deity. Craftsmen produced Mayan censers in many sizes, some just a few inches in height, others, several feet tall.

Christian use

Eastern churches

Chain censer

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Church, as well as the Eastern Catholic Churches, censers (Greek: thymiateria) are similar in design to the Western thurible. This fourth chain passes through a hole the hasp and slides in order to easily raise the lid. There will often be 12 small bells attached to the chains, symbolising the preaching of the Twelve Apostles, where one of the bells has been silenced to symbolize the rebel Judas.[28] In some traditions the censer with bells is normally used only by a bishop. Before a deacon begins a censing, he will take the censer to the priest (or the bishop, if he is present) for a blessing. The censers, charcoal and incense are kept in the diaconicon (sacristy) Entrance with the censer at Great Vespers.

The censer is used much more frequently in the Eastern churches: typically at every vespers, matins, and Divine Liturgy, as well as pannikhidas (memorial services), and other occasional offices. If a deacon is present, he typically does much of the censing; otherwise, the priest will perform the censing. Unordained servers or acolytes are permitted to prepare and carry the censer, but may not swing it during prayers. Liturgical Censing is the practice of swinging a censer suspended from chains towards something or someone, typically an icon or person, so that smoke from the burning incense travels in that direction. Burning incense represents the prayers of the church rising towards Heaven.[28] One commonly sung psalm during the censing is "Let my prayer arise in Thy sight as incense, and let the lifting up of my hands be an evening sacrifice."[29] When a deacon or priest performs a full censing of the temple (church building), he will often say Psalm 51 quietly to himself.

Hand censer

In addition to the chain censer described above, a "hand censer" (Greek: Κατσί katzi or katzion) is used on certain occasions. This device has no chains and consists of a bowl attached to a handle, often with bells attached. The lid is normally attached to the bowl with a hinge.

In Greek practice, particularly as observed on Mount Athos, during the portion of Vespers known as "Lord, I cry unto Thee" the ecclesiarch (sacristan) and his assistant will perform a full censing of the temple and people using hand censers.

Some churches have the practice of not using the chain censer during Holy Week, even by a priest or bishop, substituting for it the hand censer as a sign of humility, repentance and mourning over the Passion of Christ. They return to using the chain censer just before the Gospel reading at the Divine Liturgy on Great Saturday.

Some Orthodox Christians use a standing censer on their icon corner (home altar).

Western churches

In the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and some other groups, the censer is often called a thurible, and used during important offices (benedictions, processions, and important Masses). A common design for a thurible is a metal container, about the size and shape of a coffee-pot, suspended on chains. The bowl contains hot coals, and the incense is placed on top of these. The thurible is then swung back and forth on its chains, spreading the fragrant smoke.

A famous thurible is the Botafumeiro, in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Suspended from the ceiling of the cathedral, the swinging of this 5-foot (1.5 m) high, 55 kilogram silver vessel is an impressive sight.[28]

One of the explanations for the great size of the Botafumeiro is that in the early days it was used to freshen the air in the cathedral after being visited by droves of travel-weary pilgrims. It was also once believed that the incense smoke guarded against contracting the many diseases that plagued the populace in past centuries.[28]

Some thuribles were based on an architectural motif, for example the Gozbert Censer from the Cathedral of Trier inspired by the Temple of Solomon.[30]

Hindu use

Hindus have traditionally used an earthen censer called a Dhunachi for burning incense with coal, though coconut husk is also used. The vessel has a flared shape with a curved handle and an open top. There are also brass and silver versions.

Gallery

Incense burner from Assur, Iraq. Circa 2400 BC. The Pergamon Museum, Berlin

Incense burner from Assur, Iraq. Circa 2400 BC. The Pergamon Museum, Berlin Chinese Western Han inlaid bronze hill censer

Chinese Western Han inlaid bronze hill censer Bronze incense burner inlaid with gold; from the tomb of Liu Sheng, Prince of Zhongshan, at Hebei Mancheng, Chinese Western Han period, 2nd century BC

Bronze incense burner inlaid with gold; from the tomb of Liu Sheng, Prince of Zhongshan, at Hebei Mancheng, Chinese Western Han period, 2nd century BC Gilt-bronze Incense Burner of Baekje, National Treasure of Korea No. 287

Gilt-bronze Incense Burner of Baekje, National Treasure of Korea No. 287 Chinese porcelain stool (1575-1600) with Ottoman metallic mounting and modifications (1618) for use as an incense burner Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.

Chinese porcelain stool (1575-1600) with Ottoman metallic mounting and modifications (1618) for use as an incense burner Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum. Incense burner of the Wenchang Temple in Yilan County, Taiwan

Incense burner of the Wenchang Temple in Yilan County, Taiwan- Insect-Cage Incense Burner, late 19th to early 20th century, by Tetsunao, Japan.

- Rabbit-shaped censer, Japan, 19th century, sentoku with cloisonne top

Japanese koro, 1890, from the Khalili Collection of Japanese Art

Japanese koro, 1890, from the Khalili Collection of Japanese Art British pottery pastille burner, c. 1821-1850

British pottery pastille burner, c. 1821-1850

- Censer for an Altar Cross, 1150-1175 AD, German, Lower Saxony. Cleveland Museum of Art

- Copper ally censer from Kashmir, 9th–10th Centuries AD, British Museum[31]

Thurible with bells

Thurible with bells- Brass incense burner at Jaffna museum, Sri Lanka.

A large censer in front of the Taipei Baoan temple

A large censer in front of the Taipei Baoan temple

References

- The Regency Redingote, October, 2013

- Piotrovsky M.B. and Rogers, J.M. (eds), Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands, p. 87, 2004, Prestel, ISBN 3791330551

- P. Morrisroe. Transcribed by Kevin Cawley. "Catholic Encyclopedia".

- "Scents of earth". www.scents-of-earth.com.

- Erickson, Susan N. (1992). "Boshanlu: Mountain Censers of the Western Han Period: A Typological and Iconological Analysis", Archives of Asian Art 45:6-28.

- Needham, Joseph and Lu Gwei-Djen (1974). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology; Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. p. 133.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, a Study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press. p. 155.

- Erickson (1992), p. 15.

- Needham and Lu (1974), p. 150.

- Needham and Lu (1974), p. 151.

- Needham and Lu (1974), p. 154.

- Bedini, Silvio A. The Trail of Time = Shih-Chien Ti Tsu-Chi : Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia . Cambridge ;: Cambridge University Press, 1994. Print.

- Rowland, Benjamin (1971). Art in Afghanistan: Objects from the Kabul Museum. London: The Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0713900682.

- Allan, James W. (1981). Nishapur : metalwork of the early Islamic period. New York : The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 43. ISBN 978-0300192834.

- Piotrovsky M.B. and Rogers, J.M. (eds), Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands, pp 86-87, 2004, Prestel, ISBN 3791330551

- Maguer, Sterenn Le (Summer 2010). "Typology of incense-burners of the Islamic period". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41: 173–185. JSTOR 41622131.

- "Incense Burner of Amir Saif al-Dunya wa'l-Din ibn Muhammad al-Mawardi". The MET. Nov 16, 2019.

- Ward, Rachel (1993). Islamic Metalwork. London: British Museum Press. pp. 12. ISBN 978-0500277317.

- Maguer, Sterenn Le (Summer 2010). "Typology of incense-burners of the Islamic period". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 41: 173–185. JSTOR 41622131.

- Japanese-Incense. "Buddhist Incense – Sonae ko".

- Bruhns, Karen Olsen. “Plumbate Origins Revisited.” American Antiquity, vol. 45, no. 04, 1980, pp. 845–848., doi:10.2307/280154.

- Feinman, Gary M., and Dorie Reents-Budet. "Painting the Maya Universe: Royal Ceramics of the Classic Period." The Hispanic American Historical Review 75, no. 3 (1995): 457. doi:10.2307/2517243.

- Morehart, Christopher T., Abigail Meza Peñaloza, Carlos Serrano Sánchez, Emily Mcclung De Tapia, and Emilio Ibarra Morales. "Human Sacrifice During the Epiclassic Period in the Northern Basin of Mexico." Latin American Antiquity 23, no. 04 (2012): 426-48. doi:10.7183/1045-6635.23.4.426.

- Feinman, Gary M., and Dorie Reents-Budet. "Painting the Maya Universe: Royal Ceramics of the Classic Period." The Hispanic American Historical Review 75, no. 3 (1995): 457. doi:10.2307/2517243.

- Culler, Judith L. Incense Burners. Gettysburg Pa: Gettysburg College/Gettysburg Pa., 1961. Print.

- Coe, Michael D. The Maya, Seventh Edition. 2005.

- Rice, P.M. 1999, ‘Rethinking Classic lowland Maya pottery censers’, Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 10, no.1, pp.25-50.

- Herrera, Matthew D. Holy Smoke: The Use of Incense in the Catholic Church Archived 2012-09-12 at the Wayback Machine. San Luis Obispo: Tixlini Scriptorium, 2011.

- Psalm 141:2, New International Version

- Gomez-Moreno, Carmen (1968). Medieval Art from Private Collections A Special Exhibition at The Cloisters October 30, 1968, through March 30, 1969. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 89.

- British Museum Collection