Katana

A katana (刀 or かたな) is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. It was used by the samurai of ancient and feudal Japan.

| Katana (刀) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Sword |

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Production history | |

| Produced | Muromachi period (1392–1573) to present |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 1.1–1.5 kg |

| Blade length | approx. 60–80 cm (24–29 1⁄2 in) |

| Blade type | Curved, single-edged |

| Hilt type | Two-handed swept, with circular or squared guard |

| Scabbard/sheath | Lacquered wood |

Etymology and loanwords

The katana belongs to the nihontō family of swords, and is distinguished by a blade length (nagasa) of more than 2 shaku, approximately 60 cm (24 in).[2]

Katana can also be known as dai or daitō among Western sword enthusiasts, although daitō is a generic name for any Japanese long sword, literally meaning "big sword".[3]

As Japanese does not have separate plural and singular forms, both katanas and katana are considered acceptable forms in English.[4]

Pronounced [katana], the kun'yomi (Japanese reading) of the kanji 刀, originally meaning dao or knife/saber in Chinese, the word has been adopted as a loanword by the Portuguese.[5] In Portuguese the designation (spelled catana) means "large knife" or machete.[5]

Description

The katana is generally defined as the standard sized, moderately curved (as opposed to the older tachi featuring more curvature) Japanese sword with a blade length greater than 60.6 cm (23 1⁄2 inches) (Japanese 2 Shaku).[6] It is characterized by its distinctive appearance: a curved, slender, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard (tsuba) and long grip to accommodate two hands.[6]

With a few exceptions, katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other, if signed, by the location of the signature (mei) on the tang (nakago). In general, the mei should be carved into the side of the nakago which would face outward when the sword was worn. Since a tachi was worn with the cutting edge down, and the katana was worn with the cutting edge up, the mei would be in opposite locations on the tang.[7]

Western historians have said that katana were among the finest cutting weapons in world military history.[8][9][10]

History

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

- Jōkotō (ancient swords, until around 900 CE)

- Kotō (old swords from around 900–1596)

- Shintō (new swords 1596–1780)

- Shinshintō (newer swords 1781–1876)

- Gendaitō (modern swords 1876–1945)[11]

- Shinsakutō (newly made swords 1953–present)[12]

The first use of katana as a word to describe a long sword that was different from a tachi occurs as early as the Kamakura Period (1185–1333).[6] These references to "uchigatana" and "tsubagatana" seem to indicate a different style of sword, possibly a less costly sword for lower-ranking warriors. The evolution of the tachi into what would become the katana seems to have continued during the early Muromachi period (1337 to 1573). Starting around the year 1400, long swords signed with the katana-style mei were made. This was in response to samurai wearing their tachi in what is now called "katana style" (cutting edge up). Japanese swords are traditionally worn with the mei facing away from the wearer. When a tachi was worn in the style of a katana, with the cutting edge up, the tachi's signature would be facing the wrong way. The fact that swordsmiths started signing swords with a katana signature shows that some samurai of that time period had started wearing their swords in a different manner.[13][14]

Katana took over from tachin and became popular among samurai because the battles in Japan gradually changed from individual cavalry battles to close-up battles in which large groups fought on foot, and Katana clearly became mainstream in the late Muromachi period.[15] The quicker draw of the sword was well suited to combat where victory depended heavily on short response times. The katana further facilitated this by being worn thrust through a belt-like sash (obi) with the sharpened edge facing up. Ideally, samurai could draw the sword and strike the enemy in a single motion. Previously, the curved tachi had been worn with the edge of the blade facing down and suspended from a belt.[6][16]

The length of the katana blade varied considerably during the course of its history. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, katana blades tended to have lengths between 70 and 73 centimetres (27 1⁄2 and 28 3⁄4 in). During the early 16th century, the average length dropped about 10 centimetres (4 in), approaching closer to 60 centimetres (23 1⁄2 in). By the late 16th century, the average length had increased again by about 13 centimetres (5 in), returning to approximately 73 centimetres (28 3⁄4 in).[16]

The katana was often paired with a smaller companion sword, such as a wakizashi, or it could also be worn with a tantō, a smaller, similarly shaped dagger. The pairing of a katana with a smaller sword is called the daishō. Only samurai could wear the daishō: it represented their social power and personal honour.[6][16][17]

Modern katana (gendaitō)

During the Meiji period, the samurai class was gradually disbanded, and the special privileges granted to them were taken away, including the right to carry swords in public. The Haitōrei Edict in 1876 forbade the carrying of swords in public except for certain individuals, such as former samurai lords (daimyō), the military, and the police.[18] Skilled swordsmiths had trouble making a living during this period as Japan modernized its military, and many swordsmiths started making other items, such as farm equipment, tools, and cutlery. Military action by Japan in China and Russia during the Meiji period helped revive interest in swords, but it was not until the Shōwa period that swords were produced on a large scale again.[19] Japanese military swords produced between 1875 and 1945 are referred to as guntō (military swords).[20]

During the pre-World War II military buildup, and throughout the war, all Japanese officers were required to wear a sword. Traditionally made swords were produced during this period, but in order to supply such large numbers of swords, blacksmiths with little or no knowledge of traditional Japanese sword manufacture were recruited. In addition, supplies of the Japanese steel (tamahagane) used for swordmaking were limited, so several other types of steel were also used. Quicker methods of forging were also used, such as the use of power hammers, and quenching the blade in oil, rather than hand forging and water. The non-traditionally made swords from this period are called shōwatō, after the regnal name of the Emperor Hirohito, and in 1937, the Japanese government started requiring the use of special stamps on the tang (nakago) to distinguish these swords from traditionally made swords. During this period of war, older antique swords were remounted for use in military mounts. Presently, in Japan, shōwatō are not considered to be "true" Japanese swords, and they can be confiscated. Outside Japan, however, they are collected as historical artifacts.[18][19][21]

Post-World War II

Between 1945 and 1953, sword manufacture and sword-related martial arts were banned in Japan. Many swords were confiscated and destroyed, and swordsmiths were not able to make a living. Since 1953, Japanese swordsmiths have been allowed to work, but with severe restrictions: swordsmiths must be licensed and serve a five-year apprenticeship, and only licensed swordsmiths are allowed to produce Japanese swords (nihonto), only two longswords per month are allowed to be produced by each swordsmith, and all swords must be registered with the Japanese Government.[22]

Outside Japan, some of the modern katanas being produced by western swordsmiths use modern steel alloys, such as L6 and A2. These modern swords replicate the size and shape of the Japanese katana and are used by martial artists for iaidō and even for cutting practice (tameshigiri).

Mass-produced swords including iaitō and shinken in the shape of katana are available from many countries, though China dominates the market.[23] These types of swords are typically mass-produced and made with a wide variety of steels and methods.

Types of katana

Katana are distinguished by their type of blade:

- Shinogi-Zukuri is the most common blade shape for Japanese katana that provides both speed and cutting power. It features a distinct yokote: a line or bevel that separates the finish of the main blade and the finish of the tip. Shinogi-zukuri was originally produced after the Heian period.

- Shobu-Zukuri is a variation of shinogi-zukuri without a yokote, the distinct angle between the long cutting edge and the point section. Instead, the edge curves smoothly and uninterrupted into the point.

- Kissaki-Moroha-Zukuri is a katana blade shape with a distinctive curved and double-edged blade. One edge of the blade is shaped in normal katana fashion while the tip is symmetrical and both edges of the blade are sharp.

Forging and construction

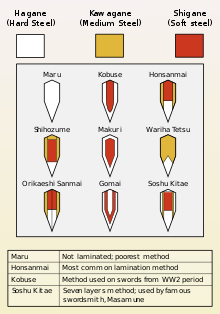

Katana are traditionally made from a specialized Japanese steel called tamahagane,[24] which is created from a traditional smelting process that results in several, layered steels with different carbon concentrations.[25] This process helps remove impurities and even out the carbon content of the steel. The age of the steel plays a role in the ability to remove impurities, with older steel having a higher oxygen concentration, being more easily stretched and rid of impurities during hammering, resulting in a stronger blade.[26] The smith begins by folding and welding pieces of the steel several times to work out most of the differences in the steel. The resulting block of steel is then drawn out to form a billet.

At this stage, it is only slightly curved or may have no curve at all. The katana's gentle curvature is attained by a process of differential hardening or differential quenching: the smith coats the blade with several layers of a wet clay slurry, which is a special concoction unique to each sword maker, but generally composed of clay, water and any or none of ash, grinding stone powder, or rust. This process is called tsuchioki. The edge of the blade is coated with a thinner layer than the sides and spine of the sword, heated, and then quenched in water (few sword makers use oil to quench the blade). The slurry causes only the blade's edge to be hardened and also causes the blade to curve due to the difference in densities of the micro-structures in the steel.[16] When steel with a carbon content of 0.7% is heated beyond 750 °C, it enters the austenite phase. When austenite is cooled very suddenly by quenching in water, the structure changes into martensite, which is a very hard form of steel. When austenite is allowed to cool slowly, its structure changes into a mixture of ferrite and pearlite which is softer than martensite.[27][28] This process also creates the distinct line down the sides of the blade called the hamon, which is made distinct by polishing. Each hamon and each smith's style of hamon is distinct.[16]

After the blade is forged, it is then sent to be polished. The polishing takes between one and three weeks. The polisher uses a series of successively finer grains of polishing stones in a process called glazing, until the blade has a mirror finish. However, the blunt edge of the katana is often given a matte finish to emphasize the hamon.[16]

Usage in martial arts

Katana were used by samurai both in the battlefield and for practicing several martial arts, and modern martial artists still use a variety of katana. Martial arts in which training with katana is used include iaijutsu, battōjutsu, iaidō, kenjutsu, kendō, ninjutsu and Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū.[29][30][31]

Storage and maintenance

If mishandled in its storage or maintenance, the katana may become irreparably damaged. The blade should be stored horizontally in its sheath, curve down and edge facing upward to maintain the edge. It is extremely important that the blade remain well-oiled, powdered and polished, as the natural moisture residue from the hands of the user will rapidly cause the blade to rust if not cleaned off. The traditional oil used is chōji oil (99% mineral oil and 1% clove oil for fragrance). Similarly, when stored for longer periods, it is important that the katana be inspected frequently and aired out if necessary in order to prevent rust or mold from forming (mold may feed off the salts in the oil used to polish the blade).[32]

Ownership and trade restrictions

Republic of Ireland

Under the Firearms and Offensive Weapons Act 1990 (Offensive Weapons) (Amendment) Order 2009, katanas made post-1953 are illegal unless made by hand according to traditional methods.[33]

United Kingdom

As of April 2008, the British government added swords with a curved blade of 50 cm (20 in) or over in length ("the length of the blade shall be the straight line distance from the top of the handle to the tip of the blade") to the Offensive Weapons Order.[34] This ban was a response to reports that samurai swords were used in more than 80 attacks and four killings over the preceding four years.[35] Those who violate the ban would be jailed up to six months and charged a fine of £5,000. Martial arts practitioners, historical re-enactors and others may still own such swords. The sword can also be legal provided it was made in Japan before 1954, or was made using traditional sword making methods. It is also legal to buy if it can be classed as a "martial artist's weapon". This ban applies to England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This ban was amended in August 2008 to allow sale and ownership without licence of "traditional" hand-forged katana.[36]

Gallery

.png)

_katana_met_museum.jpg) Antique Japanese katana, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Antique Japanese katana, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Antique Japanese katana, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Antique Japanese katana, Metropolitan Museum of Art..jpg) Japanese katana showing a horimono (blade carving), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Japanese katana showing a horimono (blade carving), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

See also

- Kenjutsu

- Iaidō

- Japanese sword mountings

- Japanese sword

- Daishō

- Ōdachi

- Tachi

- Uchigatana

- Wakizashi

- Tenka-Goken (Five Swords under Heaven) - five individual swords traditionally viewed as the best katanas

- Backsword

- Broadsword

- Japanese swords in fiction

- Korean sword

References

- 刀 金象嵌銘城和泉守所持 正宗磨上本阿 (in Japanese). National Institutes for Cultural Heritage.

- "How Long Is a Katana?". Medieval Swords World. 3 August 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Sun-Jin Kim (1996). Tuttle Dictionary Martial Arts Korea, China & Japan. Tuttle Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8048-2016-5.

- Adrian Akmajian; Richard A. Demers; Ann K. Farmer; Robert M. Harnish (2001). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 624. ISBN 9780262511230.

- Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado; Anthony X. Soares (1988). Portuguese Vocables in Asiatic Languages: From the Portuguese Original of Monsignor Sebastiao Rodolfo Dalgado. South Asia Books. p. 520. ISBN 978-81-206-0413-1.

- Kanzan Sato (1983). The Japanese Sword: A Comprehensive Guide (Japanese arts Library). Japan: Kodansha International. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87011-562-2.

- 土子民夫 (May 2002). 日本刀21世紀への挑戦. Kodansha International. p. 30. ISBN 978-4-7700-2854-9.

- Stephen Turnbull (2012). Katana: The Samurai Sword. Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9781849086585.

- Roger Ford (2006). Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor. DK Publishing. pp. 66, 120. ISBN 9780756622107.

- Anthony J. Bryant and Angus McBride (1994) Samurai 1550–1600. Osprey Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 1855323451

- Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press. pp. 40–58. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8.

- トム岸田 (24 September 2004). 靖国刀. Kodansha International. p. 42. ISBN 978-4-7700-2754-2.

- Stephen Turnbull (8 February 2011). Katana: The Samurai Sword. Osprey Publishing. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-84908-658-5.

- Kōkan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 28. ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0.

- 日本刀の歴史 The Japanese Sword Museum

- Leon Kapp; Hiroko Kapp; Yoshindo Yoshihara (1987). The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Japan: Kodansha International. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-87011-798-5.

- Oscar Ratti; Adele Westbrook (1991). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Tuttle Publishing. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7.

- Kōkan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 43. ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0.

- Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8.

- John Yumoto (13 December 2013). The Samurai Sword: A Handbook. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 6, 70. ISBN 978-1-4629-0706-9.

- Leon Kapp; Hiroko Kapp; Yoshindo Yoshihara (January 2002). Modern Japanese Swords and Swordsmiths: From 1868 to the Present. Kodansha International. pp. 58–70. ISBN 978-4-7700-1962-2.

- Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8.

- Steve Shackleford (7 September 2010). "Sword Capitol of the World". Spirit Of The Sword: A Celebration of Artistry and Craftsmanship. Iola, Wisconsin: Adams Media. p. 23. ISBN 1-4402-1638-X.

- 鉄と生活研究会 (2008). トコトンやさしい鉄の本. 日刊工業新聞社. ISBN 978-4-526-06012-0.

- Secrets of the Samurai Sword. Pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- "Step 1: Types of Katana Swords". Katana Sword Reviews. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Richard Cohen (18 December 2007). By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions. Random House Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-307-43074-8.

- James Drewe (15 February 2009). Tàijí Jiàn 32-Posture Sword Form. Singing Dragon. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84642-869-2.

- Mason Smith (December 1997). "Stand and Deliver". Black Belt magazine. Active Interest Media, Inc. 35 (12): 66. ISSN 0277-3066.

- Graham Priest; Damon Young (21 August 2013). Martial Arts and Philosophy: Beating and Nothingness. Open Court. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8126-9723-0.

- Thomas A. Green; Joseph R. Svinth (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-1-59884-243-2.

- Gordon Warner; Donn F. Draeger (2005). Japanese Swordsmanship: Technique and Practice. Boston, Massachusetts: Weatherhill. pp. 110–131. ISBN 978-0834802360.

- "S.I. No. 338/2009 — Firearms and offensive Weapons Act 1990 (offensive Weapons) (Amendment) Order 2009". Irish Statute Book, Government of Ireland. 28 August 2009.

- The Criminal Justice Act 1988 (Offensive Weapons)(Amendment) Order 2008. Opsi.gov.uk (2010-11-19). Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- "Ban on imitation Samurai swords". BBC News. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

Calls for a ban came after a number of high-profile incidents in which cheap Samurai-style swords had been used as a weapon. The Home Office estimates there have been some 80 attacks in recent years involving Samurai-style blades, leading to at least five deaths.

- EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE ACT 1988 (OFFENSIVE WEAPONS) (AMENDMENT No. 2): ORDER 2008. opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

Further reading

- Perrin, Noel (1980). Giving Up the Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879. Boston: David R. Godine. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-87773-184-9.

- Robinson, H. Russell (1969). Japanese Arms and Armor. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

- S. Alexander Takeuchi (aka T). "Dr. T's 'Nihonto Random Thoughts' Page". Florence, AL: Department of Sociology, University of North Alabama. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010.

- Yumoto, John M (1958). The Samurai Sword: A Handbook. Boston: Tuttle Publishing. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8048-0509-4.

- Satō, Kanzan (1983). The Japanese Sword. Kodansha International. ISBN 9780870115622.