Kendo

Kendo (剣道, kendō, lit. 'sword way', 'sword path' or 'way of the sword')[1] is a traditional Japanese martial art, which descended from swordsmanship (kenjutsu) and uses bamboo swords (shinai) and protective armour (bōgu). Today, it is widely practiced within Japan and many other nations across the world.

| |

| Focus | Weaponry |

|---|---|

| Hardness | Semi-contact |

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Creator | - |

| Parenthood | kenjutsu |

| Olympic sport | No |

| Official website | kendo-fik |

Kendo is an activity that combines martial arts practices and values with strenuous sport-like physical activity.

History

Swordsmen in Japan established schools of kenjutsu [2] (the ancestor of kendo), which continued for centuries and which form the basis of kendo practice today.[3] The formal kendo exercises known as kata were developed several centuries ago as kenjutsu practice for warriors. They are still studied today, in a modified form.[4]

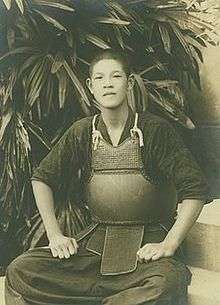

The introduction of bamboo practice swords and armour to sword training is attributed to Naganuma Shirōzaemon Kunisato during the Shotoku Era (1711–1715). Naganuma developed the use of this armor and established a training method using bamboo swords.[5]

Also, the inscription on the gravestone of Yamada Heizaemon Mitsunori's (Ippūsai) (山田平左衛門光徳(一風斎), 1638–1718) third on Naganuma Shirōzaemon Kunisato (長沼 四郎左衛門 国郷, 1688–1767), the 8th headmaster of the Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū Kenjutsu, states that his exploits included improving Japanese wooden and bamboo swords, and refining the armor by adding a metal grille to the headpiece and thick cotton protective coverings to the gauntlets. Kunisato inherited the tradition from his father Heizaemon in 1708, and the two of them, until Heizaemon's death, worked hard together to improve what would become Kendo training armor.[5][6]

Chiba Shusaku Narimasa, founder of the Hokushin Ittō-ryū Hyōhō (北辰一刀流兵法), introduced gekiken (撃剣) (full contact duels with bamboo swords and training armor) to the curriculum of tradition arts in the 1820s. Due to the large number of students of the Hokushin Ittō-ryū Hyōhō at the end of the Edo period, this contributed greatly to popularizing the use of bamboo swords and armor as a form of practice. Also there are techniques, such as Suriage-Men, Oikomi-Men etc. in modern kendo which were originally Hokushin Ittō-ryū techniques, named by Chiba Shusaku Narimasa for his school.[5][7][8][9] After the Meiji Restoration in the late 1800s Sakakibara Kenkichi popularized public gekiken for commercial gain, but also generated an increased interest in kendo and kenjutsu as a result.[10][11]

In 1876, five years after a voluntary surrender of swords, the government banned the use of swords by the surviving samurai and initiated sword hunts.[12] Meanwhile, in an attempt to standardize the sword styles (kenjutsu) used by policemen, Kawaji Toshiyoshi recruited swordsmen from various schools to come up with a unified swordsmanship style.[13] This led to the rise of the Battotai (抜刀隊, lit. Drawn Sword Corps), which mainly featured sword-wielding policemen. However, it proved difficult to integrate all sword arts, which led to a compromise of ten practice moves (kata) for police training. Difficulties of integration notwithstanding, this integration effort led to the development of kendo, which remains in use to date.[13] In 1878, Kawaji wrote a book on swordsmanship, titled Gekiken Saikō-ron (Revitalizing Swordsmanship), wherein he stressed that sword styles should not disappear with modernization, considering that other countries have been fascinated with them, but should be integrated as necessary skills for the police. He draws a particular example from his experience with the Satsuma Rebellion. The Junsa Kyōshūjo (Patrolman's Training Institute), founded in 1879, provided a curriculum that allowed policemen to study the sword arts during their off-hours (gekiken). In the same year, Kawaji wrote another book on swordsmanship, titled Kendo Saikō-ron (Revitalizing Kendo), wherein he defended the significance of such sword art training for the police.[14] While the institute remained active only until 1881, the police continued to support such practice.

The DNBK changed the name of the sporting form of swordsmanship, called gekiken, (Kyūjitai: 擊劍; Shinjitai: 撃剣, "hitting sword") to kendō in 1920.[3][15]

Kendo (along with other martial arts) was banned in Japan in 1946 by the occupying powers. This was part of "the removal and exclusion from public life of militaristic and ultra-nationalistic persons" in response to the wartime militarisation of martial arts instruction in Japan. The DNBK was also disbanded. Kendo was allowed to return to the curriculum in 1950 (first as "shinai competition" (竹刀競技, shinai kyōgi) and then as kendo from 1952).[16][17]

The All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF or ZNKR) was founded in 1952, immediately after Japan's independence was restored and the ban on martial arts in Japan was lifted.[18] It was formed on the principle of kendo not as a martial art but as educational sport, and it has continued to be practiced as such to this day.[19]

The International Kendo Federation (FIK) was founded in April 1970; it is an international federation of national and regional kendo federations and the world governing body for kendo. The FIK is a non-governmental organization, and it aims to promote and popularize kendo, iaido and jodo.[20]

The International Martial Arts Federation (IMAF), established in Kyoto 1952, was the first international organization after WWII to promote the development of martial arts worldwide. Today, IMAF includes kendo as one of the Japanese disciplines.[21]

Practitioners

Practitioners of kendo are called kendōka (剣道家), meaning "someone who practices kendo",[22] or occasionally kenshi (剣士), meaning "swordsman".[23] The old term of kendoists is sometimes used.[24]

The "Kodansha Meibo" (a register of dan graded members of the All Japan Kendo Federation) shows that as of September 2007, there were 1.48 million registered dan graded kendōka in Japan. According to the survey conducted by the All Japan Kendo Federation, the number of active kendo practitioners in Japan is 477,000 in which 290,000 dan holders are included. From these figures, the All Japan Kendo Federation estimates that the number of "kendōka" in Japan is 1.66 million, with over 6 million practitioners worldwide, by adding the number of the registered dan holders and the active kendo practitioners without dan grade.[25]

Concept and purpose

In 1975, the All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF) developed then published "The Concept and Purpose of Kendo" which is reproduced below.[26][27]

Concept

Kendo is a way to discipline the human character through the application of the principles of the katana.

Purpose

- To mold the mind and body.

- To cultivate a vigorous spirit

- And through correct and structured training,

- To strive for improvement in the art of Kendo.

- To hold in esteem courtesy and honor.

- To associate with others with sincerity.

- And to forever pursue the cultivation of oneself.

- Thus will one be able:

- To love one's country and society;

- To contribute to the development of culture;

- And to promote peace and prosperity among all people.

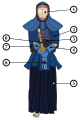

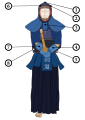

Equipment and clothing

Kendo is practiced wearing a traditional Japanese style of clothing, protective armour (防具, bōgu) and using one or, less commonly, two shinai (竹刀, shinai).[28]

Equipment

The shinai is meant to represent a Japanese sword (katana) and is made up of four bamboo slats, which are held together by leather fittings. A modern variation of a shinai with carbon fiber reinforced resin slats is also used.[29][30]

Kendōka also use hard wooden swords (木刀, bokutō) to practice kata.[31]

Kendo employs strikes involving both one edge and the tip of the shinai or bokutō.

Protective armour is worn to protect specified target areas on the head, arms, and body. The head is protected by a stylised helmet, called men (面), with a metal grille (面金, men-gane) to protect the face, a series of hard leather and fabric flaps (突垂れ, tsuki-dare) to protect the throat, and padded fabric flaps (面垂れ, men-dare) to protect the side of the neck and shoulders. The forearms, wrists, and hands are protected by long, thickly padded fabric gloves called kote (小手). The torso is protected by a breastplate (胴, dō), while the waist and groin area are protected by the tare (垂れ), consisting of three thick vertical fabric flaps or faulds.

Clothing

The clothing worn under the bōgu comprise a jacket (kendogi or keikogi) and hakama, a garment separated in the middle to form two wide trouser legs.[32]

A cotton towel (手拭い, tenugui) is wrapped around the head, under the men, to absorb perspiration and provide a base for the men to fit comfortably.

Modern practice

Kendo training is quite noisy in comparison to some other martial arts or sports. This is because kendōka use a shout, or kiai (気合い), to express their fighting spirit when striking. Additionally, kendōka execute fumikomi-ashi (踏み込み足), an action similar to a stamp of the front foot, during a strike.

Like some other martial arts, kendōka train and fight barefoot. Kendo is ideally practiced in a purpose-built dōjō, though standard sports halls and other venues are often used. An appropriate venue has a clean and well-sprung wooden floor, suitable for fumikomi-ashi.[26]

Kendo techniques comprise both strikes and thrusts. Strikes are only made towards specified target areas (打突-部位, datotsu-bui) on the wrists, head, or body, all of which are protected by armour. The targets are men, sayu-men or Yoko-men (upper, left or right side of the men), the right kote at any time, the left kote when it is in a raised position, and the left or right side of the dō. Thrusts (突き, tsuki) are only allowed to the throat. However, since an incorrectly performed thrust could cause serious injury to the opponent's neck, thrusting techniques in free practice and competition are often restricted to senior dan graded kendōka.

- Kendōka perform sonkyo after combat.

Two kendōka in tsuba zeriai.

Two kendōka in tsuba zeriai. Kendo target areas, or datotsu-bui.

Kendo target areas, or datotsu-bui. Two kendōka, one (left) is playing in nitō (two sword style) and the other (right) is playing in ittō (one sword style).

Two kendōka, one (left) is playing in nitō (two sword style) and the other (right) is playing in ittō (one sword style).

Once a kendōka begins practice in armour, a practice session may include any or all of the following types of practice.

- Kiri-kaeshi (切り返し)

- Striking the left and right men target points in succession, practising centering, distance, and correct technique, while building spirit and stamina. (see Kirikaeshi for more information)

- Waza-geiko (技稽古)

- Waza or technique practice in which the student learns and refines the techniques of Kendo with a receiving partner.

- Kakari-geiko (掛稽古)

- Short, intense, attack practice which teaches continuous alertness and readiness to attack, as well as building spirit and stamina.

- Ji-geiko (地稽古)

- Undirected practice where the kendōka tries all that has been learned during practice against an opponent.

- Gokaku-geiko (互角稽古)

- Practice between two kendōka of similar skill level.

- Hikitate-geiko (引立稽古)

- Practice where a senior kendōka guides a junior through practice.

- Shiai-geiko (試合稽古)

- Competition practice which may also be judged.

Techniques

Techniques are divided into shikake-waza (to initiate a strike) and ōji-waza (a response to an attempted strike).[26] Kendoka who wish to use such techniques during practice or competitions, often practice each technique with a motodachi. This is a process that requires patience. First practising slowly and then as familiarity and confidence build, the kendoka and motodachi increase the speed to match and competition level.

Shikake-waza

These attack techniques are used to create suki in an opponent by initiating an attack, or strike boldly when the opponent has created a suki. Such techniques include:

- Tobikomi-waza

This is a technique used when one's opponent has weak kisei (spirit, vigour) or when they yield a suki under pressure. Always hold kisei and strike quickly.

- Hikibana-waza

Body and shinai will lose balance as the initiator strikes or when being attacked. This technique takes advantage of this to help execute a strike. A good example is Hikibana-kote when a strike is made to an opponent's kote as they feel threatened and raise their kensen as the initiator pushes forward.

- Katsugi-waza

This provides a surprise attack, by lifting the shinai over the initiator's shoulder before striking. Here a skillful use of the kensen and spirited attack is crucial for effective katsugi-waza or luring the opponent into breaking his/her posture.

- Nidan-waza

There are two types. The first is for moving to the next waza after a failed first strike, and the second holds the opponent's attention and posture to create the suki for a second strike. The former requires a continuous rhythm of correct strikes. The latter requires continuous execution of waza, to take advantage of the opponent's suki.

- Harai-waza

This can be used if one's opponent's kamae has no suki when the opponent tries to attack. The opponent's shinai is either knocked down from above or swept up from below with a resulting strike just when his/her kamae is broken.

- Debana-waza

This technique involves striking the opponent as they are about to strike. This is because their concentration will be on striking and their posture will have no flexibility to respond. Thus debana-waza is ideal. This can be to any part of the opponent's body, with valid strikes being: debana-men, debana-kote, and debana-Tsuki.

Oji-waza

These counter-attack techniques are performed by executing a strike after responding or avoiding an attempted strike by the opponent. This can also be achieved by inducing the opponent to attack, then employing one of the Oji-waza.

- Nuki-waza

Avoiding an attack from another, then instantly responding. Here, timing has to be correct. A response that is too slow or fast may not be effective. Therefore, close attention to an opponent's every move is required.

- Suriage-waza

If struck by an opponent's shinai, this technique sweeps up their shinai in a rising-slide motion, with the right (ura) or left (omote) side of the shinai. Then strike in the direction of their shinai, or at the suki resulting from their composure's collapse. This technique needs to be smooth. That is, don't separate the rising-slide motion and the upward-sweeping motion or it will not be successful. Valid strikes include: men-suriage-men, kote-suriage-men, men-suriage-do, kote-suriage-kote, and Tsuki-suriage-men.

- Uchiotoshi-waza

This waza knocks an opponent's shinai to the right or left. This neutralises a potential strike and gives the ideal chance to strike as an opponent is off-balance. For success, an opponent's maai has to be correctly perceived, and then one knocks down their shinai before their arm fully extends. Valid examples are: do-uchiotoshi-men and Tsuki-uchiotoshi-men.

- Kaeshi-waza

This technique is a response. As the initiator strikes, the opponent parry's their shinai with the initiators. Then flip over (turn over the hands) and strike their opposite side. Valid strikes include:men-kaeshi-men, men-kaeshi-kote, men-kaeshi-do, kote-kaeshi-men, kote-kaeshi-kote, and do-kaeshi-men.

Rules of Competition

A scorable point (有効打突, yūkō-datotsu) in a kendo competition (tai-kai) is defined as an accurate strike or thrust made onto a datotsu-bui of the opponent's kendo-gu with the shinai making contact at its datotsu-bu, the competitor displaying high spirits, correct posture and followed by zanshin.[33]

Datotsu-bui or point scoring targets in kendo are defined as:[34]

- Men-bu, the top or sides of the head protector (sho-men and sayu-men).

- Kote-bu, a padded area of the right or left wrist protector (migi-kote and hidari-kote).

- Do-bu, an area of the right or left side of the armour that protects the torso (migi-do and hidari-do).

- Tsuki-bu, an area of the head protector in front of the throat (Tsuki-dare).

Datotsu-bu of the 'shinai' is the forward, or blade side (jin-bu) of the top third (monouchi) of the shinai.[34]

Zanshin (残心), or continuation of awareness, must be present and shown throughout the execution of the strike, and the kendōka must be mentally and physically ready to attack again.

In competition, there are usually three referees (審判, shinpan). Each referee holds a red flag and a white flag in opposing hands. To award a point, a referee raises the flag corresponding to the colour of the ribbon worn by the scoring competitor. Usually, at least two referees must agree for a point to be awarded. The match continues until a pronouncement of the point that has been scored.

Kendo competitions are usually a three-point match. The first competitor to score two points, therefore, wins the match. If the time limit is reached and only one competitor has a point, that competitor wins.

In the case of a tie, there are several options:

- Hiki-wake (引き分け): The match is declared a draw.

- Enchō (延長): The match is continued until either competitor scores a point.

- Hantei (判定): The victor is decided by the referees. The three referees vote for victor by each raising one of their respective flags simultaneously.[35]

Important Kendo competitions

The All Japan Kendo Championship is regarded as the most prestigious kendo championship. Despite it being the national championship for only Japanese kendoka, kendo practitioners all over the world consider the All Japan Kendo Championship as the championship with the highest level of competitive kendo. The World Kendo Championships have been held every three years since 1970. They are organised by the International Kendo Federation (FIK) with the support of the host nation's kendo federation.[36] The European championship is held every year, except in those years in which there is a world championship.[37] Kendo is also one of the martial arts in the World Combat Games.

Advancement

Grades

Technical achievement in kendo is measured by advancement in grade, rank or level. The kyū (級) and dan (段) grading system, created in 1883,[38] is used to indicate one's proficiency in kendo. The dan levels are from first-dan (初段, sho-dan) to tenth-dan (十段, jū-dan). There are usually six grades below first-dan, known as kyu. The kyu numbering is in reverse order, with first kyu (一級, ikkyū) being the grade immediately below first dan, and sixth kyu (六級, rokkyū) being the lowest grade. There are no visible differences in dress between kendo grades; those below dan-level may dress the same as those above dan-level.[39]

Eighth-dan (八段, hachi-dan) is the highest dan grade attainable through a test of physical kendo skills. In the AJKF the grades of ninth-dan (九段, kyū-dan) and tenth dan (十段 (jū-dan))are no longer awarded, but ninth-dan kendōka are still active in Japanese kendo. International Kendo Federation (FIK) grading rules allow national kendo organisations to establish a special committee to consider the award of those grades. Only five now-deceased kendoka were ever admitted to the rank of 10th-dan following the establishment in 1952 of the All Japan Kendo Federation. The five kendoka, all of whom had been students of Naitō Takaharu at the Budo Senmon Gakko,[40] were:

- Ogawa Kinnosuke 小川 金之助 (1884-1962)- awarded 1957

- Moriji Mochida (aka Mochida Moriji) 持田 盛二 (1885-1974)- awarded 1957

- Nakano Sousuke 中野 宗助 (1885-1963)- awarded 1957

- Saimura Gorou 斎村 五郎 (1887-1969)- awarded 1957

- Ooasa Yuuji 大麻 勇次 (1887-1974)- awarded 1962

All examination candidates face a panel of examiners. A larger, more qualified panel is usually assembled to assess the higher dan grades. Kendo examinations typically consist of jitsugi, a demonstration of the skill of the applicants, Nihon Kendo Kata and a written exam. The eighth-dan kendo exam is extremely difficult, with a reported pass rate of less than 1 percent.[41]

| Grade | Requirement | Age requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1-dan | 1-kyū | At least 13 years old |

| 2-dan | At least 1 year of training after receiving 1-dan | |

| 3-dan | At least 2 years of training after receiving 2-dan | |

| 4-dan | At least 3 years of training after receiving 3-dan | |

| 5-dan | At least 4 years of training after receiving 4-dan | |

| 6-dan | At least 5 years of training after receiving 5-dan | |

| 7-dan | At least 6 years of training after receiving 6-dan | |

| 8-dan | At least 10 years of training after receiving 7-dan | At least 46 years old |

Titles

Titles (称号, shōgō) can be earned in addition to the above dan grades by kendōka of a defined dan grade. These are renshi (錬士), kyōshi (教士), and hanshi (範士). The title is affixed to the front of the dan grade when said, for example renshi roku-dan (錬士六段). The qualifications for each title are below.

| Title | Required grade | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| renshi (錬士) | 6-dan | After receiving 6-dan, one must wait 1 or more years, pass screening by the kendo organisation, receive a recommendation from the regional organisation president then pass an exam on kendo theory. |

| kyōshi (教士) | renshi 7-dan | After receiving 7-dan, one must wait 2 or more years, pass screening by the kendo organisation, and receive a recommendation from the regional organisation president then pass an exam on kendo theory. |

| hanshi (範士) | kyōshi 8-dan | After receiving 8-dan, one must wait 8 or more years, pass screening by the kendo organisation, receive a recommendation from the regional organisation president and the national kendo organisation president then pass an exam on kendo theory. |

Kata

Kata are fixed patterns that teach kendoka the basic elements of swordsmanship. The kata include fundamental techniques of attacking and counter-attacking, and have useful practical application in general kendo. There are ten Nihon Kendō Kata (日本剣道形). These are generally practised with wooden swords (木刀, bokutō or bokken). Occasionally, real swords or swords with a blunt edge, called kata-yō (形用) or ha-biki (刃引), may be used for display of kata.[42]

All are performed by two people: the uchidachi (打太刀), the teacher, and shidachi (仕太刀), the student. The uchidachi makes the first move or attack in each kata. As this is a teaching role, the uchidachi is always the losing side, thus allowing the shidachi to learn and to gain confidence.[42]

Kata one to seven are performed with both partners using a normal length wooden sword. Kata eight to ten are performed with uchidachi using a normal length weapon and shidachi using a shorter one (kodachi).[42]

The forms of the Nihon Kendō Kata (日本剣道形) were finalised in 1933 based on the Dai nihon Teikoku Kendo Kata, composed in 1912.[43] "It is impossible to link the individual forms of Dai nihon Teikoku Kendo Kata to their original influences, although the genealogical reference diagram does indicate the masters of the various committees involved, and it is possible from this to determine the influences and origins of Kendo and the Kata."[44]

In 2003, the All Japan Kendo Federation introduced Bokutō Ni Yoru Kendō Kihon-waza Keiko-hō (木刀による剣道基本技稽古法), a set of basic exercises using a bokuto. This form of practice, is intended primarily for kendōka up to second dan (二段, ni-dan), but is very useful for all kendo students which are organised under FIK.[42]

Kata can also be treated as competitions where players are judged upon their performance and technique.[45][46]

National and international organisations

Many national and regional organisations manage and promote kendo activities outside Japan. The major organising body is the International Kendo Federation (FIK). The FIK is a non-governmental international federation of national and regional kendo organisations. An aim of the FIK is to provide a link between Japan and the international kendo community and to promote and popularise kendo, iaido and jodo. The FIK was established in 1970 with 17 national federations. The number of affiliated and recognised organisations has increased over the years to 57 (as of May 2015).[47] The FIK is recognised by SportAccord as a 'Full Member'.[48] and by the World Anti-Doping Agency.[49]

Other organisations that promote the study of Japanese martial arts, including kendo, are the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (DNBK) and the International Martial Arts Federation (IMAF). The current DNBK has no connection to the pre-war organisation, although it shares the same goals. The International Martial Arts Federation (IMAF) was established in Kyoto in 1952 and is dedicated to the promotion and development of the martial arts worldwide, including kendo.[21]

Kendo magazine

Kendo Jidai and Kendo Nippon offer Kendo magazines in Japanese and Kendo Jidai also offer Kendo Jidai International in English. This is the world's only English-language kendo magazine.

See also

- Angampora

- Banshay

- Bataireacht

- Bōjutsu

- Fencing

- Gatka

- Gendai budō - modern Japanese martial arts

- Iaidō - sword drawing

- Jōdō - a martial art using a short wooden staff, or stick

- Jūkendō

- Kalaripayattu

- Kenjutsu

- Krabi–krabong

- Kumdo - Korean kendo

- Kuttu Varisai

- Mardani khel

- Naginata - a martial art using a glave-like weapon

- Silambam

- Silambam Asia

- Swordsmanship

- Tahtib

- Thang-ta

- Varma kalai

- World Silambam Association

References

- Larkins, Damian (24 March 2016). "Kendo: The way of the sword keeping skills sharp". ABC News. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Kenjutsu".

- Yoshio, Mifuji, ed. (31 October 2009), Budo: The Martial Ways of Japan, translated by Dr Alexander Bennett, Tokyo: Nippon Budokan Foundation, p. 335.

- Nippon Kendo Kata Instruction Manual. Tokyo: All Japan Kendo Federation. 29 March 2002. p. 1.

- "The History of Kendo". All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF). Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- Tamio, Nakamura (3 January 2007). "The History of Bogu". Kendo World. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010.

- Chiba, Eiichiro (1942). Chiba Shusaku Ikoshu. Tokyo, Japan. p. xiv. ISBN 978-4-88458-220-3.(in Japanese)

- Hall, David (25 March 2013). Encyclopedia of Japanese Martial Arts. p. xiv. ISBN 978-1568364100.(in English)

- Skoss, Diane (April 2002). Keiko Shokon (Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan). p. xiv. ISBN 978-1890536060.(in English)

- Thomas A. Green; Joseph R. Svinth (11 June 2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. p. 600. ISBN 978-1-59884-244-9.

- Sasamori, Junzo; Warner, Gordon (June 1989). This Is Kendo: The Art of Japanese Fencing. Tuttle Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8048-1607-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan: 1334–1615. Stanford: Stanford University Press. OCLC 1035605319

- Guttmann, Allen (2001). Japanese Sports: A History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9780824824648. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Sanchez Garcia, Raul (2018). The Historical Sociology of Japanese Martial Arts. Routledge. ISBN 9781351333795. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Green, Thomas A.; Svinth, Joseph R. (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. 2. ABC-CLIO. pp. 600–1. ISBN 978-1-59884-244-9.

- Svinth, J.R. (December 2002). "Documentation Regarding the Budo Ban in Japan, 1945–1950". Journal of Combative Sport (JCS). ISSN 1492-1650. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Matunobu, Yamazaki and Nojima (1989), 剣道 (Kendo), Seibido Sports Series (27), Seibido Publishers, Tokyo (in Japanese)

- Budo. The Martial Ways of Japan. Tokyo, Japan: Nippon Budokan Foundation. 1 October 2009. p. 141. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Ozawa, Hiroshi (31 July 1997). Kendo: the definitive guide. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. p. xiv. ISBN 978-4-7700-2119-9.

- International Kendo Federation

- "FAQ". International Martial Arts Federation (IMAF).

- Allison, Nancy (1999). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Body-Mind Disciplines. Taylor & Francis. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8239-2546-9.

- Tokeshi, Jinichi (2003). Kendo: Elements, Rules, and Philosophy. University of Hawaii Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-8248-2598-0.

- Sasamori & Warner 1989, p. 69

- "Zenkoku kendō jinkō chōsa no kekka matomaru Heisei 20-nen 05 tsuki-gō" 全国剣道人口調査の結果まとまる 平成20年05月号 (in Japanese). All Japan Kendo Federation. March 2008. Archived from the original on 25 August 2009.

- Sato, Noriaki (July 1995). Kendo Fundamentals. Tokyo, Japan: All Japan Kendo Federation.

- "Concept of Kendo". All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF). Archived from the original on 22 April 2017.

- Sasamori, Junzō; Warner, Gordon (1964). This is Kendo: the art of Japanese fencing. Japan: Charles E. Tuttle. pp. 71–76. ISBN 978-0-8048-0574-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sasamori & Warner 1964, p. 70

- Dilbert, Ryan (16 May 2017). "Best, Worst Uses of Kendo Stick in WWE History Ahead of Alexa Bliss vs. Bayley". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Sasamori & Warner 1964, p. 52

- Sasamori & Warner 1964, p. 71

- The Regulations of Kendo Shiai and Shinpan. Tokyo, Japan: International Kendo Federation. December 2006. p. 5.

- FIK Regulations 2006, p. 6

- FIK Regulations 2006, p. 94

- World Kendo Championships

- "European Kendo Championships". Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Active Interest Media, Inc. (1991). Black Belt. Active Interest Media, Inc. p. 64.

- Standard Rules for Dan/Kyu Examination. Tokyo, Japan: International Kendo Federation. December 2006.

- Asahi Picture News, February 1958

- "Zen'nihon kendō renmei" 全日本剣道連盟. kendo.or.jp. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Nippon Kendo Kata Instruction Manual. Tokyo, Japan: All Japan Kendo Federation. 29 March 2002.

- Budden, Paul (2000). Looking at a Far Mountain: A Study of Kendo Kata. Tuttle. pp. 9, 12, 14. ISBN 978-0-8048-3245-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Budden 2000, p. 9

- "Kendo Kata Taikai". British Kendo Association. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- "Kendo Kata Taikai Rules" (PDF). British Kendo Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "International Kendo Federation". kendo-fik.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "SportAccord Members". SportAccord Members. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "Alliance of Members of Sportaccord". WADA. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kendo. |

- International Kendo Federation (FIK)

- All Japan Kendo Federation (AJKF) (in Japanese)

- Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (DNBK)

- http://www.ekf-eu.com/ European Kendo Federation

.jpg)