Tacking (sailing)

Tacking is a sailing maneuver by which a sailing vessel, whose desired course is into the wind, turns its bow toward the wind so that the direction from which the wind blows changes from one side to the other, allowing progress in the desired direction.[1] The opposite maneuver to tacking is called jibing, or wearing on square-rigged ships, that is, turning the stern through the wind. No sailing vessel can move directly upwind, though that may be the desired direction, making this an essential maneuver of a sailing ship. A series of tacking moves, in a zig-zag fashion, is called beating, and allows sailing in the desired direction.

This maneuver is used for different effects in races, where one ship is not only sailing in a desired direction, but also concerned with slowing the progress of competitors.

The need for tacking

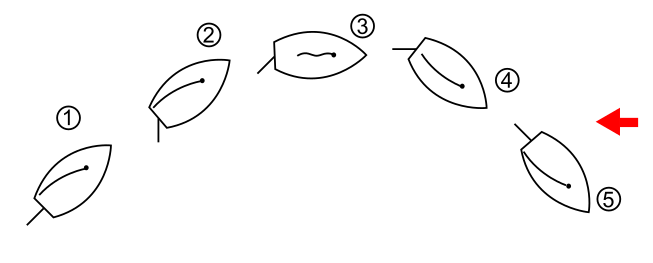

Sailing ships cannot proceed directly into the wind, but often need to go in that direction. Movement is achieved by tacking. If a vessel is sailing on a starboard tack with the wind blowing from the right side and tacks, it will end up on a port tack with the wind blowing from the left side. See the accompanying image; the red arrow indicates the wind direction. This maneuver is frequently used when the desired direction is (nearly) directly into the wind.

In practice, the sails are set at an angle of 45° to the wind for conventional sailships and the tacking course is kept as short as possible before a new tack is set in. Rotor ships can tack much closer to the wind, 20 to 30°.

The opposite maneuver, i.e. turning the stern through the wind, is called jibing (or wearing on square-rigged ships). Tacking more than 180° to avoid a jibe (mostly in harsh conditions) is sometimes referred to as a 'chicken jibe'.[2]

Technical usage

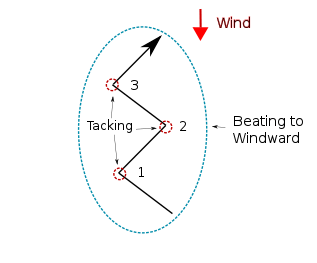

Tacking is sometimes confused with beating to windward, which is a process of beating a course upwind and generally implies (but does not require) actually coming about. In the accompanying figure, the boat is seen to tack three times while beating to windward.

When used without a modifier, the term "tacking" is always synonymous with "coming about"; however, some find it acceptable to say "tack downwind"; i.e., change tack by jibing rather than coming about. Racers often use this maneuver because most modern sailboats (especially larger boats with spinnakers and a variety of staysails) sail substantially faster on a broad reach than when running "dead" downwind. The extra speed gained by zigzagging downwind can more than make up for the extra distance that must be covered. Cruising boats also often tack downwind when the swells are also coming from dead astern (i.e., there is a "following sea"), because of the more stable motion of the hull.

About is defined as: "To go about is to change the course of a ship by tacking. Ready about, or boutship, is the order to prepare for tacking."[3]

Beating

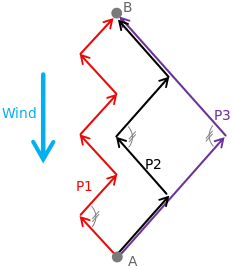

Beating is the procedure by which a ship moves on a zig-zag course to make progress directly into the wind (upwind). No sailing vessel can move directly upwind (though that may be the desired direction). Beating allows the vessel to advance indirectly upwind.

A ship that is beating will sail as close to the wind as possible; this position is known as close hauled. In general, the closest angle to the wind that a ship can sail is around 35 to 45 degrees. Some modern yachts can sail very near to the wind, while older ships, especially square-rigged ships, are much worse at it.

Thus when a ship is tacking, it is moving both upwind and across the wind. Crosswind movement is not desired, and may be very much undesirable, if for instance the ship is moving along a narrow channel.

Therefore, the ship changes tack periodically, reversing the direction of cross-wind movement while continuing the upwind movement. The interval between tacks depends (in part) on the lateral space available: in a small navigable channel, tacks may be required every few minutes, while in the open ocean days may pass between tacks, provided that the wind continues to come from the same general direction.

In older vessels that could not sail close to the wind, beating could be an expensive process that required sailing a total distance several times the distance actually traveled upwind.

Tacking strategy

Favorable tacks "lifts" and "headers"

When beating to windward, often your desired destination although still in the no sail zone, is not aligned directly upwind - to the eye of the wind. In this case one tack becomes more favorable than the other - it angles more closely in the direction you wish to travel than the other tack does. Then the best strategy is to stay on this favorable tack as much as possible, and shorten the time you need to sail on the unfavorable tack. This will result in a faster passage with less wasted effort. Your overall course then is not an equal zig-zag as in the diagrams above, but more of a saw tooth pattern. If while on this tack the wind shifts in your favor, called a "lift," and allows you to point up even more, so much the better, then this tack is even more favorable. But if the wind shifts against you and makes you fall off, called a "header," then the opposite tack may become the more favorable course.[4]

Best course

Since conditions are always changing somewhat, a sailor must keep evaluating which tack, port or starboard is actually the most favorable. So with these concepts in mind, when the desired destination is exactly to windward, the most efficient strategy is given by the old racing adage to "Tack on a header." This is true because if before the wind changed both tacks were exactly equal – neither one was more favorable, then since a header on one tack is automatically a lift on the other, the opposite tack has just become the more favorable one and the helmsman should tack and change course for the most efficient passage.[4]

Tacking duels

Sailing courses laid out for racing purposes always have one leg directly to windward. This is where the highest sailing skills often form the essence of the race. Sail trim and keeping the boat moving most efficiently are of the utmost importance. In these circumstances tacking duels will often develop.

Any boat in clear air to windward has an aerodynamic advantage over other boats. To keep this advantage the lead boat will often try to "blanket" the trailing boat(s) by maneuvering to keep them in the disturbed foul air she is creating to her lee. This involves constant anticipation and balancing many different dynamic factors. Conversely the trailing boats will try to overtake or otherwise escape the bad air blanket created by the lead boat and head for clear air without losing too much speed or momentum.

A tacking duel develops when two or more boats execute multiple usually excessive course changes (tacking) in very close quarters. This often involves bending, or breaking, the safety right-of-way-rules, and intentionally creating dangerous and threatening conditions between the dueling boats. Each skipper is trying to gain the lead and the advantage of clear air. This can sometimes become counter-productive as some speed and time is always lost in each tack.

For various sailing craft

The method of tacking of sailing craft differs, depending on whether they are fore-and aft, square-rigged, a windsurfer, or a kitesurfer.

- Fore-and-aft rig – A fore-and-aft rig permits the wind to flow past the sail, as the craft head through the eye of the wind. Modern rigs pivot around a stay or the mast, while this occurs. For a jib, the old leeward sheet is released as the craft heads through the wind and the old windward sheet is tightened as the new leeward sheet to allow the sail to draw wind. Mainsails are often self-tending and slide on a traveler to the opposite side.[5] On certain rigs, such as lateens[6] and luggers,[7] the sail may be partially lowered to bring it to the opposite side.

- Square rig – Unlike with a fore-and-aft rig, a square-rigged vessel's sails must be presented squarely to the wind and thus impede forward motion as they are swung around via the yardarms through the wind as controlled by the vessel's running rigging, using braces—adjusting the fore and aft angle of each yardarm around the mast—and sheets attached to the clews (bottom corners) of each sail to control the sail's angle to the wind.[8] The procedure is to turn the vessel into the wind with the hind-most fore-and-aft sail (the spanker), pulled to windward to help turn the ship through the eye of the wind. Once the ship has come about, all the sails are adjusted to align properly with the new tack. Because square-rigger masts are more strongly braced from behind than from ahead, tacking is a dangerous procedure in strong winds. The ship may lose forward momentum (become caught in stays) and the rigging may fail from the wind coming from ahead. Under these conditions, the choice may be to wear ship—to turn the away from the wind and around 240° onto the next tack (60° off the wind).[9]

- Windsurfer rig – Sailors of windsurfers tack by walking forward of the mast and letting the sail swing into the wind as the board moves through the eye of the wind; once on the opposite tack, the sailor realigns the sail on the new tack. In strong winds on a small board, an option is the fast tack, whereby the board is turned into the wind at planing speed as the sailor crosses in front of the flexibly mounted mast and reaches for the boom on the opposite side and continues planing on the new tack.[10]

- Kitesurfer rig – When changing tack, a kitesurfer rotates the kite end-for-end to align with the new apparent wind direction. Kite boards are designed to be used exclusively while planing; many are double-ended to allow an immediate change of course in the opposite direction.[11]

See also

- Jibe (or Gybe)

- Racing Rules of Sailing

- Tack (as used to describe a section of a sail)

- Glossary of nautical terms

References

- Keegan, John (1989). The Price of Admiralty. New York: Viking. p. 281. ISBN 0-670-81416-4.

- McEwen, Thomas (2006). Boater's Pocket Reference: Your Comprehensive Resource for Boats and Boating. Anchor Cove Publishing. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-9774052-0-6.

- A naval encyclopædia: comprising a dictionary of nautical words and phrases; biographical notices, and records of naval officers; special articles of naval art and science. Philadelphia: LR Hamersly & Co. 1881. Retrieved January 23, 2014. at Internet Archive

- Royce, Patrick M. (2015). Royce's Sailing Illustrated. 2 (11 ed.). ProStar Publications. p. 161. ISBN 9780911284072.

- Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals (Revised ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4391-3678-2.

- Campbell, I.C. (1995), "The Lateen Sail in World History" (PDF), Journal of World History, 6 (1), pp. 1–23, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-04, retrieved 2017-06-16

- Skeat, Walter W. (2013). An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Dover language guides (Reprint ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-486-31765-6.

- Biddlecombe, George (1990). The Art of Rigging: Containing an Explanation of Terms and Phrases and the Progressive Method of Rigging Expressly Adapted for Sailing Ships. Dover Maritime Series. Courier Corporation. p. 13. ISBN 9780486263434.

- Findlay, Gordon D. (2005). My Hand on the Tiller. AuthorHouse. p. 138. ISBN 9781456793500.

- Hart, Peter (2014). Windsurfing. Crowood. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-84797-963-6.

- Gratwick, Andy (2015). The Kiteboarding Manual: The essential guide for beginners and improvers. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-4081-9204-7.