Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a town in Cumbria, North-West England. Historically part of Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. At the tip of the Furness peninsula, close to the Lake District, it is bordered by Morecambe Bay, the Duddon Estuary and the Irish Sea. In 2011, Barrow's population was 57,000, making it the second largest urban area in Cumbria after Carlisle. Natives of Barrow, as well as the local dialect, are known as Barrovian.[1]

| Barrow-in-Furness | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from the upper left: Central Barrow with the skyline of Blackpool also visible, Barrow Island, Walney Bridge and Furness College, Furness Abbey, Ramsden Square, Dock Museum and DDH, Barrow Town Hall and St. Mary's Church | |

Coat of arms of Barrow-in-Furness | |

Barrow-in-Furness Location within Cumbria | |

| Population | 56,745 (2011 Census) |

| Demonym | Barrovian |

| OS grid reference | SD198690 |

| • London | 297 mi (478 km) |

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BARROW-IN-FURNESS |

| Postcode district | LA13, LA14 |

| Dialling code | 01229 |

| Police | Cumbria |

| Fire | Cumbria |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

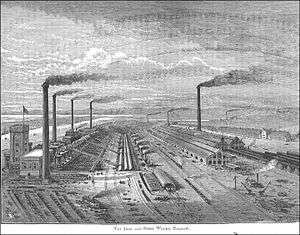

In the Middle Ages, Barrow was a small hamlet within the parish of Dalton-in-Furness with Furness Abbey, now on the outskirts of the modern-day town, controlling the local economy before its dissolution in 1537. The iron prospector Henry Schneider arrived in Furness in 1839 and, with other investors, opened the Furness Railway in 1846 to transport iron ore and slate from local mines to the coast. Further hematite deposits were discovered, of sufficient size to develop factories for smelting and exporting steel. For a period of the late 19th century, the Barrow Hematite Steel Company-owned steelworks was the world's largest.[2]

Barrow's location and the availability of steel allowed the town to develop into a significant producer of naval vessels, a shift that was accelerated during World War I and the local yard's specialisation in submarines. The original iron- and steel-making enterprises closed down after World War II, leaving Vickers shipyard as Barrow's main industry and employer. Several Royal Navy flagships, the vast majority of its nuclear submarines as well as numerous other naval vessels, ocean liners and oil tankers have been manufactured at the facility.

The end of the Cold War and subsequent decrease in military spending saw high unemployment in the town through lack of contracts; despite this, the BAE Systems shipyard remains operational as the UK's largest by workforce (9,500 employees in 2020) and is now undergoing a major expansion associated with the Dreadnought-class submarine programme.[3] Today Barrow is also a hub for energy generation and handling. Offshore wind farms form one of the highest concentrations of turbines in the world, including the second largest offshore farm, with multiple operating bases in Barrow.[4]

Toponymy

The name was originally that of an island, Barrai, which can be traced back to 1190. This was later renamed Old Barrow, recorded as Oldebarrey in 1537, and Old Barrow Insula and Barrohead in 1577. The island was then joined to the mainland and the town took its name. The name itself seems to mean "island with promontory", combining British barro- and Old Norse ey, but it is more likely that Scandinavian settlers simply accepted barro- as a meaningless name, and so added an explanatory Old Norse second element.[5]

Nicknames

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Barrow was nicknamed "the English Chicago" because of the sudden and rapid growth in its industry, economic stature and overall size.[6] More recently the town has been dubbed the "capital of blue-collar Britain" by the Daily Telegraph, reflecting its strong working class identity.[7] Barrow is also often jokingly referred to as being at the end of the longest cul-de-sac in the country because of its isolated location at the tip of the Furness peninsula.[8]

History

Early history

Barrow and the surrounding area has been settled non-continuously for several millennia with evidence of Neolithic inhabitants on Walney Island. Despite a rich history of Roman settlement across Cumbria and the discovery of related artefacts in the Barrow area, no buildings or structures have been found to support the idea of a functioning Roman community on the Furness peninsula.[9] The Furness Hoard discovery of Viking silver coins and other artefacts in 2011 provided significant archaeological evidence of Norse settlement in the early 9th century. Several areas of Barrow including Yarlside and Ormsgill, as well as "Barrow" and "Furness", have names of Old Norse origin. The Domesday Book of 1086 recorded the settlements of Hietun, Rosse and Hougenai, which are now the districts of Hawcoat, Roose and Walney respectively.

In the Middle Ages the Furness peninsula was controlled by the Cistercian monks of the Abbey of St Mary of Furness, known as Furness Abbey. This was located in the "Vale of Nightshade", now on the outskirts of the town.[10] Founded for the Savigniac order, it was built on the orders of King Stephen in 1123. Soon after the abbey's foundation the monks discovered iron ore deposits, later to provide the basis for the Furness economy. These thin strata, close to the surface, were extracted through open cut workings,[11] which were then smelted by the monks.[12] The proceeds from mining, along with agriculture and fisheries, meant that by the 15th century the abbey had become the second richest and most powerful Cistercian abbey in England, after Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire.[13] The monks of Furness Abbey constructed a wooden tower on nearby Piel Island in 1212 which acted as their main trading point; it was twice invaded by the Scots, in 1316 and 1322. In 1327 King Edward III gave Furness Abbey a licence to crenellate the tower, and a motte-and-bailey castle was built. However Barrow itself was just a hamlet in the parish of Dalton-in-Furness, reliant on the land and sea for survival. Small quantities of iron and ore were exported from jetties on the channel separating the village from Walney Island. Amongst the oldest buildings in Barrow are several cottages and farmhouses in Newbarns (now a ward of the borough) which date back to the early 17th century; as well as Rampside Hall, a Grade I listed building and the best-preserved in the town from the 1600s. Even as late as 1843 there were still only 32 dwellings, including two pubs.[14]

19th century

In 1839 Henry Schneider arrived as a young speculator and dealer in iron, and he discovered large deposits of haematite in 1850. He and other investors founded the Furness Railway, the first section of which opened in 1846, to transport the ore from the slate quarries at Kirkby-in-Furness and haematite mines at Lindal-in-Furness and Askam and Ireleth to a deep-water harbour near Roa Island.[15] The crucial and difficult link across Morecambe Bay between Ulverston and Carnforth on the main line was promoted, as the Ulverston and Lancaster Railway, by a group led by John Brogden and opened in 1857. It was promptly purchased by the Furness Railway.[16][17]

The docks built between 1863 and 1881 in the more sheltered channel between the mainland and Barrow Island replaced the port at Roa Island. The first dock to open was Devonshire Dock in 1867, and Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone stated his belief that "Barrow would become another Liverpool". The increasing quantities of iron ore mined in Furness were then brought into the centre of Barrow to be transported by sea.

The investors in the burgeoning mining and railway industries decided that greater profits could be made by smelting the iron ore and converting the resultant pig-iron into steel, and then exporting the finished product. Schneider and James Ramsden, the railway's general manager, erected blast furnaces at Barrow that by 1876 formed the largest steelworks in the world.[18] Its success was a result of the availability of local iron ore and coal from the Cumberland mines and easy rail and sea transport. The Furness Railway, which counted local aristocrats William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Buccleuch as investors, kick-started the Industrial Revolution on the peninsula. The railway brought mined ore to the town, where the steelworks produced large quantities of steel. It was used for shipbuilding, and derived products such as rails were also exported from the newly built docks.[15]

Barrow's population grew rapidly. Population figures for the town itself were not collected until 1871,[19] though sources suggest that Barrow's population was still as low as 700 in 1851.[20] During the first half of the 19th century, Barrow formed part of the parish of Dalton-in-Furness, the population of which shows some of Barrow's early growth from the 1850s:

Population of the Parish of Dalton-in-Furness[19]

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,954 | 2,074 | 2,446 | 2,697 | 3,231 | 4,683 | 9,152 |

In 1871 Barrow's population was recorded at 18,584 and in 1881 at 47,259, less than forty years after the railway was built.[19] The majority of migrants originated from elsewhere in Lancashire although significant numbers settled in Barrow from Ireland and Scotland, which represented 11% and 7% of the local population in the 1890s.[21][22] By the turn of the 20th century, the Scottish-born population had increased to form the highest portion anywhere in England. In an attempt to diversify Barrow's economy James Ramsden founded the Barrow and Calcutta Jute Company in 1870 and the Barrow Jute Works was soon constructed alongside the Furness Railway line in Hindpool. The mill employed 2,000 women at its peak and was awarded a gold medal for its produce at the 1878 Paris Exposition Universelle.[23]

The sheltered strait between Barrow and Walney Island was an ideal location for the shipyard. The first ship to be built, the Jane Roper, was launched in 1852; the first steamship, a 3,000-ton liner named Duke of Devonshire, in 1873. Shipbuilding activity increased, and on 18 February 1871 the Barrow Shipbuilding Company was incorporated. Barrow's relative isolation from the United Kingdom's industrial heartlands meant that the newly formed company included several capabilities that would usually be subcontracted to other establishments. In particular, a large engineering works was constructed including a foundry and pattern shop, a forge, and an engine shop. In addition, the shipyard had a joiners' shop, a boat-building shed and a sailmaking and rigging loft.[24]

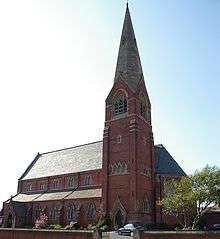

During these boom years, Ramsden proposed building a planned town to accommodate the large workforce which had arrived. There are few planned towns in the United Kingdom, and Barrow is one of the oldest. Its centre contains a grid of well-built terraced houses, with a tree-lined road leading away from a central square. Ramsden later became the first mayor of Barrow,[25] which was given municipal borough status in 1867, and county borough status in 1889.[26] The imposing red sandstone town hall, designed by W.H. Lynn, was built in a neo-gothic style in 1887.[27] Prior to this, the borough council had met at the railway headquarters: the railway company's control of industry extended to the administration of the town itself.

.jpg)

The Barrow Shipbuilding Company was taken over by the Sheffield steel firm of Vickers in 1897, by which time the shipyard had surpassed the railway and steelworks as the largest employer and landowner in Barrow. The company constructed Vickerstown, modelled on George Cadbury's Bournville, on the adjacent Walney Island in the early 20th century to house its employees.[28] It also commissioned Sir Edwin Lutyens to design Abbey House as a guest house and residence for its managing director, Commander Craven.[29]

20th century

By the 1890s the shipyard was heavily engaged in the construction of warships for the Royal Navy and also for export. The Royal Navy's first submarine, Holland 1, was built in 1901,[30] and by 1914 the UK had the most advanced submarine fleet in the world, with 94% of it constructed by Vickers. Vickers was also famous for the construction of airships and airship hangars during the early 20th century. Originally constructed in a large shed at Cavendish Dock, production later relocated to Barrow/Walney Island Airport. HMA No. 1, nicknamed the Mayfly is the most notable airship to have been built in Barrow. The first of its kind in the UK it came to an untimely end on 24 September 1911 when it was wrecked by wind during trials. Well-known ships built in Barrow include Mikasa, the Japanese flagship during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, the liner SS Oriana and the aircraft carriers HMS Invincible and HMAS Melbourne. It should also be noted that there was a significant presence of Vickers' armament division in Barrow with the huge Heavy Engineering Workshop on Michaelson Road supplying ammunition for the British Army and Royal Navy throughout both world wars. World War 1 brought significant temporary migration as workers arrived to work in the munitions factory and shipyard, with the town's population reaching to an estimated peak of around 82,000 during the War.[19] Thousands of local men fought abroad during World War I, 616 were ultimately killed in action.[31]

During World War II, Barrow was a target for the German air force looking to disable the town's shipbuilding capabilities (see Barrow Blitz).[32] The town suffered the most in a short period between April and May 1941. During the war, a local housewife, Nella Last, was selected to write a diary of her experiences on the home front for the Mass-Observation project. Her memoirs were later adapted for television as Housewife, 49 starring Victoria Wood. The difficulty in targeting bombs meant that the shipyards and steelworks were often missed, at the expense of the residential areas. Ultimately, 83 people were killed and 11,000 houses in the area were left damaged. To escape the heaviest bombardments, many people in the central areas left the town to sleep in hedgerows, with some being permanently evacuated. Barrow's industry continued to supply the war effort, with Winston Churchill visiting the town on one occasion to launch the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable.[33] Besides the dozens of civilians killed during World War II, some 268 Barrovian men were also killed whilst in combat.[31]

Barrow's population reached a second peak in of 77,900 in 1951;[34] however, by this point the long decline of mining and steel-making as a result of overseas competition and dwindling resources had already begun. The Barrow ironworks closed in 1963,[35] three years after the last Furness mine shut. The by then small steelworks followed suit in 1983,[36] leaving Barrow's shipyard as the town's principal industry. From the 1960s onwards it concentrated its efforts in submarine manufacture, and the UK's first nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought, was constructed in 1960. HMS Resolution, the Swiftsure, Trafalgar and Vanguard-class submarines all followed. The last of these are armed with Trident II missiles as part of the British government's Trident nuclear programme.

The end of the Cold War in 1991 marked a reduction in the demand for military ships and submarines, and the town continued its decline. The shipyard's dependency on military contracts at the expense of civilian and commercial engineering and shipbuilding meant it was particularly hard hit as government defence spending was reduced dramatically.[37] As a result, the workforce shrank from 14,500 in 1990 to 5,800 in February 1995,[38] with overall unemployment in the town rising over that period from 4.6% to 10%.[3] The rejection by the VSEL management of detailed plans for Barrow's industrial renewal in the mid-to-late 1980s remains controversial.[39] This has led to renewed academic attention in recent years to the possibilities of converting military-industrial production in declining shipbuilding areas to the offshore renewable energy sector.[40]

21st century

In a 2002 outbreak of legionellosis in the town, 172 people were reported to have caught the disease, of whom seven died. This made it the fourth worst outbreak in the world in terms of number of cases and sixth worst in terms of deaths. The source of the bacteria was later found to be steam from a badly maintained air conditioning unit in the council-run arts centre Forum 28.[41]

At the conclusion of the inquest into the seven deaths, the coroner for Furness and South Cumbria criticised the council for its health and safety failings.[42] In 2006, council employee Gillian Beckingham and employer Barrow Borough Council were cleared of seven charges of manslaughter. Beckingham, the council senior architect was fined £15,000 and the authority £125,000. Following the trials the contractor responsible for maintaining the plant settled a £1.5 million claim by the council for damages.[43] The borough council was the first public body in the country to face corporate manslaughter charges.[44]

2006 saw the construction of Barrow Offshore Wind Farm, which has acted as a catalyst for further investment in offshore renewable energy. Ormonde Wind Farm and Walney Wind Farm followed in 2011, the latter of which became the largest offshore wind farm in the world. The three wind farms are located west of Walney Island and are operated primarily by DONG Energy, contain a total of 162 turbines and have a combined nameplate capacity of 607 MW, providing energy for well over half a million homes. West of Duddon Sands Wind Farm was commissioned in 2014 while Walney was extended in 2018 to again become the world's largest such offshore facility.

During the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic, Barrow had the highest rate of infection of any local authority in the United Kingdom. This was attributed to various socio-economic factors and a high level of testing also seen in the neighbouring authorities of South Lakeland and Lancaster.[45]

Governance

Barrow is the largest town in the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness[46] and the largest settlement in the peninsula of Furness. The borough is the direct inheritor of the municipal and county borough charters given to the town in the late 19th century.[47] Historically it is part of the Hundred of Lonsdale 'north of the sands' in the historic county boundaries of Lancashire.[48] Since the local government reforms enacted in England in 1974 the town has been within the administrative county of Cumbria. It still forms a part of the Duchy of Lancaster. The Barrow-in-Furness Borough Council forms the 'lower' tier of local government under Cumbria County Council.[49] Since the 2011 local election, the Labour Party has had overall control of the Borough council, while the Borough elected 10 Labour and one Conservative Party councillor at the 2013 Cumbria County election. The town, along with Walney Island, is unparished and forms the bulk of the wards which make the entire borough's area. The Mayor and Deputy Mayor of Barrow are elected annually, and hold the roles of chairman and Vice-Chairman of Barrow-in-Furness Borough Council.[50] The borough and former county borough of Barrow-in-Furness have been served by 107 mayors, beginning with Sir James Ramsden in 1867 and continuing through to incumbent 2019 mayor William McEwan.[50]

The Barrow-in-Furness UK Parliament constituency first came into existence during the 1885 United Kingdom general election, with David Duncan of the Liberal Party becoming the first MP for the town. The seat was won by the Conservative Party in 1892, before being won for the first time by Labour in 1906. In the subsequent 40 years the seat swung between Conservative and Labour, but since 1945 it has been generally considered a Labour safe seat.[51] In 1983, the constituency was expanded to include several commuter towns such as Dalton-in-Furness and Ulverston and was renamed Barrow and Furness. It was subsequently won by the Conservatives, with the victory attributed to Labour's stance against the nuclear-powered submarines that were being constructed in Barrow.[51] Following a change in Labour policy the party won Barrow and Furness in 1992. John Woodcock was the MP for the constituency between the 2010 and 2019 general election, when Conservative Simon Fell succeeeded as MP for the Borough.

| Council/ Electoral wards of Barrow-in-Furness |

|

Barrow Island | Central | Hawcoat | Hindpool | Newbarns | Ormsgill | Parkside | Risedale | Roosecote | Walney North | Walney South |

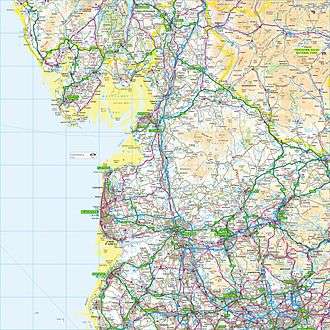

Geography

Barrow is situated at the tip of the Furness peninsula on the north-western edge of Morecambe Bay, south of the Duddon Estuary and east of the Irish Sea. Walney Island, surrounds the peninsula's Irish Sea coast and is separated from Barrow by the narrow Walney Channel. Both Morecambe Bay and the Duddon Estuary are characterized by large areas of quicksand and fast-moving tidal bores. Areas of sand dunes exist on coasts surrounding Barrow, particularly at Roanhead and North Walney. The town centre and major industrial areas sit on a fairly flat coastal shelf, with hillier ground rising to the east of the town, peaking at 94 metres (310 ft) at Yarlside. Barrow sits on soils deposited during the end of the Ice Age, eroded from the mountains of the Lake District National Park, 10 miles (15 km) to the north-east. Barrow's soils are composed of glacial lake clay and glacial till, while Walney is almost entirely made up of reworked glacial morraine.[52][53] Beneath these soils is a sandstone bedrock, from which many of the town's older buildings are constructed.[53]

Barrow town centre is located to the north-east of the docks, with suburbs also extending to the north and east, as well as onto Walney. The towns of Dalton-in-Furness and Askam-in-Furness are the other sizable settlements of the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. Barrow is the only major urban area in South Cumbria, with the nearest settlements of a similar size being Lancaster and Morecambe. Other towns nearby include Ulverston, Millom, Grange-over-Sands, Kendal and Windermere.

Map of Barrow

Map of Barrow Aerial view of Barrow and Walney Island

Aerial view of Barrow and Walney Island Barrow within North West England (top left)

Barrow within North West England (top left)

Islands

Most of the town is sheltered from the Irish Sea by Walney Island, a 14 mile (22.5 km) long island connected to the mainland by the bascule type Jubilee bridge. About 13,000 live on the isle's various settlements, mostly in Vickerstown, which was built to house workers in the rapidly expanding shipyard. Another significant island which lay in the Walney Channel was Barrow Island, but following the filling of the channel to create land for the shipyard it is now directly connected to the town. Other islands which lie close to Barrow are Piel Island, whose castle protected the harbour from marauding Scots, Sheep Island, Roa Island and Foulney Island.

Parks and open spaces

There are numerous natural and managed public parks and open spaces within Barrow. Walney North and South Nature Reserves are protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, as is Sandscale Haws. Formal woodland areas within the town include Hawcoat/Ormsgill Quarry, How Tun Woods, Abbotswood, Barrow Steel Works & Slag Bank and Sowerby Wood. The 45-Acre Barrow Park is the largest and most centrally located man-made park in the town with smaller parks including Channelside Haven, Hindpool Urban Park and Vickerstown Park. There are also 25 council-owned playgrounds and 15 allotments.

Climate

Barrow on the west coast of Great Britain has a temperate maritime climate owing to the North Atlantic current and tends to have milder winters than central and eastern parts of the country. The town lies in Hardiness zone 9 and has an average yearly temperature of 10.4 °C.

| Climate data for Barrow-in-Furness, England, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13 (55) |

14 (57) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

27 (81) |

31 (88) |

33 (91) |

33 (92) |

27 (80) |

23 (74) |

16 (61) |

14 (57) |

33 (92) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7 (44) |

8 (46) |

9 (49) |

12 (53) |

15 (59) |

17 (62) |

19 (66) |

19 (67) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

13 (55) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4 (39) |

4 (39) |

4 (40) |

6 (43) |

8 (47) |

11 (52) |

13 (56) |

13 (56) |

12 (53) |

9 (49) |

7 (44) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10 (14) |

−9 (16) |

−9 (15) |

−4 (24) |

−2 (29) |

2 (36) |

4 (39) |

3 (37) |

0 (32) |

−5 (23) |

−7 (20) |

−11 (12) |

−11 (12) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71 (2.80) |

67 (2.65) |

64 (2.50) |

54 (2.13) |

55 (2.17) |

61 (2.42) |

56 (2.22) |

68 (2.69) |

86 (3.39) |

110 (4.35) |

92 (3.62) |

85 (3.36) |

869 (34.3) |

| Source: MSN Weather[54] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Population

The Barrow council district, which includes adjacent urban areas, had a population of around 69,100 according to the 2011 census. This is 4% less than the 2001 figure of 71,900, and the highest percentage population loss in the country between 2001 and 2011.[55][56] The Office for National Statistics states Barrow's population as being in long term decline with a projected population of around 65,000 by 2037. This is largely a result of negative net migration.[57]

Ethnicity and language

The 2011 census states 96.9% of Barrow's population as White British, and ethnic minority populations in Barrow stood at 3.1%.[58] Other ethnic groups in Barrow include Other White 1.3%, Asian 1.0%, Mixed Race 0.5%, Black 0.1%, Arab 0.1% and all other ethnic groups represented 0.1% of the population. The first people to settle in what is now Barrow were the Celts and Scandinavians followed by the Cornish. Most Barrovians however are descended from immigrants from Scotland, Ireland and other parts of England who arrived from the late 19th century onwards. Barrow has sizeable Chinese (in particular those originating from Hong Kong), Filipino, Indian, Thai and Kosovan communities as well as a Polish population which partly dates back to World War II, however in general Barrow has a much lower proportion of ethnic minorities than national average.[58]

Barrow's Chinese connections were the subject of a documentary on Chinese state television in 2014.[59] The programme covered diplomat Li Hongzhang's fact finding mission to the town's steelworks and shipyard in 1896 as well as the 2012 discovery of a hoard of Chinese coins discovered in Barrow dated around a similar time that have been suggested as having been brought over by sailors or labourers.[59] The Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding is a charity with a branch based in Barrow that aims to develop relations with the British Chinese community and the general British population. It was established in 1975 and publishes the quarterly China Eye magazine.

In 2011 93.2% of the borough's population was born in England, 2.6% in Scotland, 0.6% in Northern Ireland and 0.5% in Wales. 3.1% of the town's 2011 population were born elsewhere in the world, 1.3% of which were born in the European Union. The five most common foreign countries of birth were Poland, the Republic of Ireland, Germany, the Philippines and India.[60]

According to the 2011 census, 98.8% of Barrovians spoke English as a main language, although around 40 languages are spoken in the town with Polish, Chinese, and Tagalog prevailing as the second, third and fourth most common main languages (0.3%, 0.2% and 0.1% of the population respectively).[61] Of the 797 Barrovians who had a main language other than English, 82.9% can speak English well to very well.[62]

Religion

In the 2011 census 70.7% of Barrow's population stated themselves as being Christian. People stating no religion or chose not to state totalled 28.4% combined. Other religious groups represented 0.9% of the population, with Islam and Buddhism prevailing as the first and second most common groups.[63] Conishead Priory, the first Kadampa Buddhist centre in the west, is home to around 100 Buddhists and is located off the Barrow to Ulverston Coast Road within the South Lakeland district.[64] Historically Barrow was home to a notable Ashkenazi Jewish community that peaked in size during the 1930s with a synagogue in the town. Nonetheless, it closed in 1974 and only a dozen Jews were recorded by the 2011 census.[65]

Economy

Historically Barrow's economy was dominated by the manufacturing sector, with the Barrow Hematite Steel Company and Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering being amongst the most important global companies in their respective fields during the 20th century. In the present day, manufacturing remains the largest employment sector in the town. BAE Systems is the single largest employer with around 9,500 employees, and one third of the workforce, as at 2020. However, like most of the UK, employment trends have greatly diversified since the 20th century and there are no other predominant employment sectors in Barrow.

Shipyard and port

Barrow has played a vital role in global ship and submarine construction for around 150 years. Ottoman submarine Abdül Hamid was built in the town in 1886 and became the first submarine in the world to fire a live torpedo underwater, while oil tanker British Admiral became the first British vessel to exceed 100,000 tonnes when launched in 1965. The vast majority of all current and former Royal Navy submarines were constructed in Barrow as well as numerous Royal Navy Fleet Flagships.

.jpg)

The BAE Systems Maritime – Submarines shipyard at Barrow is the largest in the UK by workforce ahead of BAE Systems Maritime – Naval Ships in Govan. It was expanded in 1986 by construction of a new covered assembly facility, the Devonshire Dock Hall (DDH), completed by Alfred McAlpine, on land that was created by infilling part of the Devonshire Dock with 2.4 million tonnes of sand pumped from nearby Roosecote Sands.[66] DDH is the tallest building in Cumbria at 51 m. With a length of 268 m (879 ft), width of 51 m (167 ft) and an area of 25,000 square metres (270,000 sq ft) it is one of the largest shipbuilding construction complex of its kind in Europe.[67]

The DDH provides a controlled environment for ship and submarine assembly, and avoids the difficulties caused by building on the slope of traditional slipways. Outside the hall, a 24,300 tonne capacity shiplift allows completed vessels to be lowered into the water independently of the tide. Vessels can also be lifted out of the water and transferred to the hall.[68] The first use of the DDH was for construction of the Vanguard-class submarines, and later vessels of the Trafalgar class were also built there. The shipyard is currently constructing the Astute-class submarines, the first of which was launched on 8 June 2007.[69] BAE Systems is currently studying the design of a new class of ballistic missile submarines. BAE Systems also has orders for submarine pressure domes for the Spanish Navy.[70]

The shipyard has been awarded contracts for the construction of submarines which will carry nuclear missiles in a successor programme to the current Vanguard class containing the Trident system.[71] BAE Systems is investing £300 million in Barrow's shipyard to construct buildings capable of manufacturing and assembling the new class of submarines. This major development is the largest in 25 years at the shipyard and will see thousands of new jobs created, further cementing its place as the UK's largest shipyard and one of the few to have seen continuous contracts since founding over a century ago.[71]

The most recent surface vessels to be constructed in Barrow were Wave-class tanker RFA Wave Knight and Albion-class amphibious assault ships HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark in the early 2000s when the shipyard was part of BAE Systems Marine division. It also undertook fitting out and commissioning of helicopter carrier HMS Ocean in the mid-1990s after the ship was built by Kvaerner Govan in Glasgow.

Associated British Ports Holdings owns and operates the Port of Barrow which can berth vessels up to 200 m (660 ft) long and with a draught of 10 m (33 ft). The four main docks include Buccleuch Dock, Cavendish Dock, Devonshire Dock and Ramsden Dock, with the latter handling almost all of the port's cargo. Buccleuch and Devonshire Docks are utilised primarily by BAE Systems, while Cavendish Dock the largest by surface area is now a reservoir. Principal traffic includes the export of condensate by-product from the production of gas at the Rampside Gas Terminal, wood pulp and locally quarried limestone which is exported to Scandinavia for use in the paper industry. The port, which has deep water access, also handles the shipment of nuclear fuels and radioactive waste for BNFL's nearby Sellafield plant.[72]

James Fisher & Sons, a service provider in all sectors of the marine industry and a specialist supplier of engineering services to the nuclear industry in the UK and abroad,[73] was founded in Barrow in 1847.[74] It is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is the largest company to have its headquarters situated in Cumbria.[75] Annual revenue stood at £307 million in 2012 (up 15% from £268 million in 2011), as well as staff numbers standing at over 1,500 worldwide, with 120 of those in the Barrow headquarters.[75][76] Numerous vessels are registered at the Port of Barrow, with the majority being owned by James Fisher & Sons and International Nuclear Services/Pacific Nuclear Transport Limited.

Energy generation

In 1985, gas was discovered in Morecambe Bay, and to this day the products have been processed onshore at Rampside Gas Terminal in south Barrow.[77] The complex is operated jointly by Centrica and ConocoPhillips. Directly adjacent to Rampside Gas Terminal is Roosecote Power Station which was the first CCGT power station to supply electricity to the United Kingdom's National Grid. Although originally coal-fired, the station became gas-fired until it was mothballed in 2015.

Barrow and its wider urban area form part of 'Britain's Energy Coast',[78] and has one of the highest concentrations of wind farms in the world, the vast majority are located offshore and have been built during the early 2010s. All four of these wind farms are located off the coast of Walney Island, including the 189 turbine Walney Wind Farm, 108 turbine West Duddon wind farm, 30 turbine Barrow Offshore Wind Farm and 30 turbine Ormonde Wind Farm. Walney Wind Farm was the largest offshore wind farm in the world upon completion, in 2015 it received government consent to be trebled in size. DONG Energy and Scottish Power maintain a wind farm operations base with 30 full-time staff members at the Port of Barrow.[79]

Sellafield and Heysham nuclear power stations are also located within 25 miles (40 km) of Barrow.

Tourism and leisure

Although it is at the end of a peninsula, Barrow is only around 20 minutes from the Lake District,[80] Barrow has been referred to as a "gateway to the lakes" and "where the lakes meets the sea",[81] a status which could be enhanced by the new marina complex and planned cruise ship terminal.[82]

Barrow itself has several tourist attractions that support just over 1,000 jobs; the town saw a higher growth in tourist expenditure during the 2000s than Cumbria as a whole and had about 2.3 million overnight stays during 2008.[83] Barrow's most popular free-entry tourist attraction is the Dock Museum. The museum tells the history of Barrow (including the steelworks industry, the shipyard and the Barrow Blitz), as well as offering gallery space to local artists and schoolchildren. It is built upon and around an old graving dock.[84] Walney Island has two world-renowned nature reserves (the 130 hectare (0.5 sq mi) South Walney Nature Reserve[85] and the 650 hectare (2.5 sq mi) North Walney Nature Reserve).[86] Both nature reserves have Site of Special Scientific Interest designation, as do the Duddon Estuary and Sandscale Haws to the north of the borough. Barrow has a number of beaches which are popular in the summer with sunbathers, kitesurfers and caravanners. They include Earnse Bay, Biggar Bank, Roanhead and Rampside. The first two of these provide views of the Isle of Man and Anglesey on exceptionally clear days. The wider borough has more than 60 km of coastline.[87] The Park Leisure Centre is a fitness suite with a pool, set in the 45-acre (18 ha) Barrow Park.[88] The historic ruins of Furness Abbey and Piel Castle, which are both managed by English Heritage, are also popular tourist destinations. South Lakes Safari Zoo is one of Europe's leading conservation zoos and has been voted Cumbria's best tourist attraction in five non-consecutive years although it has a checkered history; it lies within the borough of Barrow-in-Furness on the outskirts of Dalton. The zoo underwent a multi-million pound expansion during the mid-2010s. It now holds thousands of animals and covers an area of 51 acres (21 ha) making it one of the Northern England's largest such parks.[89]

Barrow has been described as the Lake District's premier shopping town, with 'big name shops mingling with small local ones'.[88] The town centre is home to a large indoor market[90][91] and Portland Walk Shopping Centre.[92] Barrow has many retail and leisure parks for a town of its size, including Cornmill Crossing, Cornerhouse Retail Park, Hollywood Park, Hindpool Retail Park and Walney Road Retail Park.[93][94] Between them they host a number of supermarkets, electrical, home furnishing, clothing and discount stores, gyms, restaurants and Cumbria's largest cinema. Other modern visitor attractions in Barrow include the growing leisure destination at James Freel Close (consisting of an indoor kart racing complex, bowling alley, indoor skate park, trampoline centre and gym), as well as Lazer Zone in Hindpool Road's former Custom House and a similar Lazer Quest, escape room and play centre in the former Hitchens building on Buccleuch Street.

Regeneration and redevelopment

Urban regeneration has been ongoing in Barrow since the 1990s. Portland Walk Shopping Centre opened in 1998 anchored by Debenhams as part of a major reconstruction of Barrow town centre. Around the same time the Hindpool Retail Parks and Dock Museum were constructed over various former industrial sites in Barrow, including the dry dock, the Barrow Jute Works and the Barrow Steel Works.[95] Recent construction projects in the town also include the £43 million expansion of Furness College's Channelside campus,[96] £22.5 million Furness Academy new build,[97] £14.5 million central Barrow flood relief scheme,[98] £8.5 million Barrow police station,[99] £5 million town centre redevelopment scheme,[100] £4 million Scottish Power wind farm operations centre[79] as well as the North Central Renewal Area, shake up of the town's residential and retirement homes and a number of large-scale hotel schemes catering for the influx of contractors working for BAE Systems (namely Holiday Inn Express, Premier Inn and Wetherspoon).[101]

The Waterfront is an ambitious ongoing £200 million dockland regeneration project, which began in 2007. The project includes a new Barrow Marina Village which will incorporate an £8 million 400-berth marina, 650 homes, restaurants, shops, hotels and a new state of the art bridge across Cavendish Dock. A large watersports centre is also proposed, with the possibility of a cruise ship terminal. Some cruise ships are already scheduled to dock in Barrow, mainly for tourists to visit the Lake District, although there is no official cruise ship terminal yet.[102] Developments have stalled since 2010 when the Northwest Regional Development Agency was disbanded and essential government funding was lost. Despite this Barrow Borough Council has since purchased land needed to make the development a reality and currently controls 95% of the site.[103] The executive director of the council has stated construction of the Waterfront could resume by 2017 as economic prospects improve and has pledged funds to conduct a market testing exercise. The allocation of Growth Deal investment (2014–2021) will make improvements to the Barrow Waterfront Enterprise Zone far more secure [103] In 2014 a £300 million investment into the shipyard was announced by BAE Systems, in anticipation of the new generation of UK nuclear submarines.[71][104] Construction will take up to eight years and create thousands of new jobs at the shipyard thereafter.[71] Amongst proposals are an extension to the DDH complex and new buildings in the central yard area off Bridge Road on Barrow Island (a site formerly mooted for a huge construction hall for the construction of Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carrier sections which the yard failed to win contracts for), these will house pressure hull units ready for shot blasting and painting, and be a place for joining submarine equipment modules.[104] Redevelopment of the 5.8 hectare central yard area was completed in 2018 and is dominated by the Central Yard Complex Facility which measures 178 m (584 ft) long, 94 m (308 ft) wide and 41 m (135 ft) tall, only 10% smaller than the volume of the pre-expansion Devonshire Dock Hall.

Other large-scale developments associated with BAE include a 30,000 m2 (320,000 sq ft) logistics centre which was constructed in the Waterfront Business Park in 2015 and a 8,100 m2 (87,000 sq ft) central training facility which is proposed at Buccleuch Dock Road.

Other

Other major employers include the National Health Service, through Furness General Hospital, which employs 1,800 staff,[105] the Kimberly Clark paper mill, which has 400 employees,[106] BAE Systems' Land and Armaments division, Furness Building Society which is one of the 20 largest of its kind, Cumbria County Council and Barrow Borough Council. Amongst many retailers that have established themselves in Barrow, the furniture store Stollers is noted as being one of the largest shops of its kind in the UK.

Employment

According to the 2011 census, 78.2% of males aged 16–64 and females aged 16–59 in Barrow were economically active. This figure is higher than the North West and England averages.[107] 73.8% of the population was employed, which again is higher than regional and national averages; the unemployment rate stood at 5.6% which is lower than both averages.[107] Despite this the percentage of people claiming key benefits, which is independent of the unemployment figure, is much higher than both averages at 21.0%, or almost a quarter of all Barrovians of working age.[107] The most common form of benefit received was the Incapacity Benefit, claimed by 11.0% of the adult population, while 4.0% claimed Jobseeker's Allowance, which is on a par with the national average.[107]

The list below shows how many people were employed in certain sectors according to the 2011 census. Little change occurred between the 2001 and 2011 census; Barrow still has a much higher percentage of workers in the manufacturing sector than the national average, ranking third in 2011 behind Corby, Northamptonshire and Pendle, Lancashire.[108][109] The percentage working in manufacturing has increased further during the 2010s given thousands of new roles created at the shipyard in association with the Trident renewal programme.

South West Cumbria has one of the UK's most self-contained workforces, and Barrow itself has the sixth lowest proportion of people who travel outside of the country for work.[110] In 2001, 76% of the working age population in Barrow commuted within 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) for work, when compared to the England average of 54%.[111] A significant proportion of the town's population are employed at the Sellafield nuclear facility.

- Manufacturing: 6,570 employed (21.0% of the town's working population)

- Wholesale and retail trade: 4,728 (15.1%)

- Human health and social work: 4,539 (14.5%)

- Construction: 2,387 (7.6%)

- Education: 2,381 (7.6%)

- Accommodation and food service activities: 1,962 (6.3%)

- Public administration and defence: 1,913 (6.1%)

- Transport and storage: 1,296 (4.1%)

- Administrative and support service: 1,055 (3.4%)

- Professional, scientific and technical: 1,000 (3.2%)

- Information and communication: 496 (1.6%)

- Financial and insurance: 492 (1.6%)

- Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply: 441 (1.4%)

- Water supply: 264 (0.8%)

- Real estate: 221 (0.7%)

- Mining and quarrying: 165 (0.5%)

- Agriculture, forestry and fishing: 122 (0.4%)

- Other: 1,225 (3.9%)

Transport

Road

Barrow's principal road link is the A590. This runs to Barrow from the M6 motorway via Ulverston, skirting the southern Lake District.[112] Just north of Barrow is the southern end of the A595, linking the town to West Cumbria.[112] The A5087 connects Barrow's southern suburbs to Ulverston via a scenic coastal route. Abbey Road is the principal road through central Barrow, whilst Walney Bridge connects Barrow Island to Walney Island.

The possibility of a bridge link over Morecambe Bay is occasionally raised, and feasibility studies have been carried out.[113]

Bus

Bus services within the town are operated by Stagecoach North West. There is no specifically designated bus station, although many bus routes start and end near the town hall. The original bus station, since demolished, was known for its role in a 1970s television commercial for Chewits sweets.[114] As well as local suburban and village services, longer-distance buses run to Millom, Ulverston, Bowness, Windermere and Kendal.

Rail

Barrow-in-Furness railway station provides connections to Whitehaven, Workington and Carlisle to the north, via the Cumbrian Coast Line, and to Ulverston, Grange-over-Sands and Lancaster to the east, via the Furness Line – both of which connect to the West Coast Mainline. Numerous daily trains run to Manchester. The station handles over 600,000 passengers annually. Barrow has a second railway station, Roose, which serves the suburb of the same name.

Furness Abbey, Barrow's third main line station, closed in 1950. There was also a station on Barrow Island, for commuters between the shipyard and nearby towns served by the Furness Railway. This railway link was severed in 1966 when the famous cradle bridge across the docks was closed permanently for safety reasons. There were also stations at Piel, Rabbit Hill, Rampside, Ramsden Dock and Strand.

Between 1885 and 1932, the Barrow-in-Furness Tramways Company operated a double-decker tram service over several miles, primarily around central Barrow, Barrow Island and Hindpool.

Air

Barrow/Walney Island Airport (IATA airport code: BWF, ICAO: EGNL) is a former commercial airport and Royal Air Force base currently owned by BAE Systems which operates two Beechkraft King Air B200 and one B250 aircraft which fly to various destinations across the UK every weekday, including Bristol, Glasgow, London and Manchester. The airport's runways take on a triangular form, the longest runway is almost 4,000 feet (1,200 m). The airport was expanded by BAE in 2018 including the construction of a new terminal building, hangar and control tower.

Manchester Airport is the closest major airport, with direct links to Barrow railway station and about two hours away by road.

In 2018 a heliport was built on a site adjacent to Park Road, Ormsgill for energy firm Ørsted and to support the offshore energy sector.

Sea

Despite being one of the UK's leading shipbuilding centres, the Associated British Ports' Port of Barrow is only a minor port. Historically, the Isle of Man Steam Packet and the Barrow Steam Navigation Company (a subsidiary of the Furness Railway and later London, Midland and Scottish Railway) operated a number of steamers and passenger ferry services between Rampside and Ramsden Dock and Ardrossan (Scotland), Belfast (Northern Ireland), Blackpool, Douglas (Isle of Man), Fleetwood and Heysham.[115] All services had ceased operation by the mid-20th century.

For a short period during the early 1880s, transatlantic travel was possible from the town. The Anchor Line operated a fortnightly service utilising three of its steamships, Alexandria, Caledonia and Columbia, between Barrow and New York City via Dublin. There are proposals to construct a cruise ship terminal in Barrow as part of the Waterfront redevelopment project.[116]

Sport

Football

Barrow are in EFL League Two, the fourth tier of English football.[117] The team, founded in 1901, are nicknamed the Bluebirds and play their home games at the Holker Street stadium.[118] The side were members of the Football League until they failed to be re-elected in 1972.[118] In 1990, they won the FA Trophy beating Leek Town 3–0 in the final at Wembley Stadium, London.[119] Twenty years later, on 8 May 2010, Barrow repeated the feat, beating Stevenage Borough 2–1 after extra time.[120]

After 48 years in non-league football, Barrow were crowned champions of the National League on 17 June 2020, sealing their return to the Football League.

Football players born in Barrow include England internationals Emlyn Hughes[121] and Gary Stevens,[122] as well as Harry Hadley,[123] and Vic Metcalfe.[124] Of current professional footballers, Wayne Curtis,[125] Morecambe striker, and Iran Under-20 and Hibernian winger Shana Haji[126] both hail from the town.

Holker Old Boys F.C., based at Rakesmoor Lane, are the town's second most successful football team, and they play in the North West Counties Football League Division One.

Rugby

Rugby league is a well-established sport and the town is considered as one of the game's traditional heartlands at professional and amateur levels.[127] The professional team, Barrow Raiders, whose home games are at Craven Park, played in the Championship until 2011 but as of 2012, they now operate in the league below, known as League 1. In the 1950s the side played in three Challenge Cup finals, winning the last of these against Workington Town. In the 1997 reorganisation of the sport the original Barrow RLFC team merged with Carlisle Border Raiders to form Barrow Border Raiders,[128] with the word "border" later dropped. Players who were born in the town and played at a professional level include brothers Ade[129] and Mat Gardner[130] and Willie Horne.[131] The latter captained Barrow to their Challenge Cup victory and represented Great Britain at an international level. He was inducted into the "Barrow Hall of Fame" along with former Barrow players Phil Jackson and Jimmy Lewthwaite.[132]

At a local level, eight amateur rugby league teams participate in the Barrow & District League. They include Askam, Barrow Island, Dalton, Hindpool, Milliom, Roose Pioneers, Ulverston and Walney

Golf

Barrow is home to two large golf clubs. Barrow Golf Club, founded in 1922, is situated in Hawcoat and covers some 6,209 yards (5,678 m) with 18 holes.[133] Furness Golf Club, founded in 1872, is the sixth oldest golf club in England and is possibly the more famous of the two. It is located on Walney Island, just 50 yards (46 m) from the Irish Sea. It also offers an 18-hole course, a shop and other facilities.[134] The Furness Golf Centre is located on the outskirts of Barrow close to Roanhead and is home to a 14-bay driving range, golf shop, swing studio and the Fairway Hotel.[135] The hoaxer Maurice Flitcroft, known as the "world's worst golfer" lived and worked in the town.[136]

Motor sports

Barrow has staged speedway racing at three venues since the pioneer days in the late 1920s. The first track was at Holker Street. This venue had a revival for a short spell in the early to mid-1970s being utilised by the short-lived Barrow Bombers. In 1930 the sport moved to Little Park but this a somewhat hazy venue. The sport had a revival in 1978 at Park Avenue Industrial Estate but this was relatively short lived.

Bike racing

Barrow has produced a number of noteworthy motorcyclists throughout the years, such as Manx Grand Prix winner Eddie Crooks, TT Rider Dan Stewart, Speedway ace Adam Roynon and multiple British Sandtrack Champion John Pepper.

Karting

Kart racer Kristian Brierley[137] received national attention after successfully winning the internationally televised TKM Karting Festival in 2015.[138]

He followed this up by winning the opening round of the British Championship in 2016.

Brierley's first cousin Lydia Burney has also competed at national level in karting, as have multiple other 'Barrovians' such as Max Davis, Daniel Pepper,[139] Kieran Pepper, Oliver Dilks and Jake Calvert.[140]

Other sports

Barrow is home to the Walney Terriers American Football club, formed in 2011 the club originally trained at Memorial Fields on Walney Island before establishing training grounds elsewhere in Barrow and Ulverston. The Terriers play in the North West conference of the BAFA's National League alongside the likes of the Manchester Titans and Merseyside Nighthawks.

One of the town's most notable annual sporting events is the Keswick to Barrow (K2B), a 40-mile (60 km) walking and running event that has taken place every year since 1967 between Keswick and Barrow. The event has raised millions for charity and regularly sees in excess of 3,000 participants.[141]

Barrow Born Orienteer and Fell Runner Carl Hill was selected to carry the olympic torch for a stage through Morecambe in the buildup to the 2012 summer Olympics. He was nominated for this honor by his father David Hill who was proud of his sons accomplishments in running for England and Great Britain in Orienteering whilst also provided a large portion of his time to getting kids into sport.

Culture

Barrow, although one of the country's smallest local authorities, contains a wealth of natural and built heritage assets, which includes 274 Listed Buildings and four SSSIs. The 2016 Heritage Index formed by the Royal Society of Arts and the Heritage Lottery Fund placed the borough as sixth highest of 325 English districts for ‘assets’ with especially high scores relating to nationally important landscape and natural heritage assets and industrial heritage assets.[142]

Architecture

Barrow is one of Britain's few planned towns, and the spacious tree-lined avenues within the oldest parts of the town (including Central Barrow, Hindpool and Salthouse) are more akin to the layout of a much larger city.[143] The town centre is distinguished by its Victorian and Edwardian era civic buildings, such as the Town Hall, Main Public Library, former Technical School, former Central Fire Station, Salvation Army Building, Custom House, National Westminster Bank, The Duke of Edinburgh Hotel, St. George's Church, St. Mary's RC Church and St. James' Church. Oppositely, several distinctive buildings have been demolished in Barrow since the mid-20th century as a result of neglect or war damage, amongst the most iconic are Abbots Wood, Barrow Central Railway Station, Infield House, North Lonsdale Hospital, Scotch Buildings and the Waverley Hotel. Lancaster architects Sharpe, Paley and Austin were prolific throughout the development of Barrow. A number of Barrow's landmark buildings were constructed from locally sourced sandstone, evident from the high number of brown and red coloured stone buildings in the town. Similar materials were used in a number of local buildings in the early 20th century, and often accompanied by terracotta. There are also an increasing number of modern office buildings as well as the shipyard's construction halls which dominate much of Barrow's skyline. Despite much of Barrow having been constructed from the late 19th to mid 20th centuries, architectural styles vary greatly across the town from the Art Deco John Whinnerah Institute to the Byzantine style St. John's Church, Neo-Elizabethan Abbey House and Tudor Revival Vickerstown estate.

Barrow has 8 Grade I listed buildings, 15 Grade II* and 249 Grade II buildings. The majority of Grade I listed buildings and structures are in and around the Furness Abbey complex while many Grade II* listed buildings in the town are 19th century tenements on Barrow Island including the Devonshire Buildings.[144] There are a number of Conservation Areas across Barrow named as such for their architectural or historical significance, they include Barrow Island, Biggar, Central Barrow, Furness Abbey, North Scale, North and South Vickerstown and St. George's Square.[145] Historically Barrow's skyline was dominated by shipyard cranes and industrial chimneys, although little evidence of this remains in the present day with the last hammerhead crane – the iconic yellow crane of Buccleuch Dock – being dismantled in 2011, despite calls for listing status like the smaller Titan Clydebank in Glasgow. The tallest building in Barrow is Devonshire Dock Hall at 51 metres (167 ft). Also worth of note are the turbines of Ormonde Wind Farm located just off the coast of Barrow which stand at 152 metres (499 ft).

In terms of housing, the majority of dwellings in Barrow are Victorian terraces. At 47.0% of local housing stock in 2011, the figure is much higher than England's average of 24.5%. 29.7% of dwellings are semi-detached, 12.09% detached and 10.2% flats, maisonettes or apartments.[146] Great variety in housing styles is a feature across central Barrow, Barrow Island, Hindpool, and Vickerstown. Most were built around a grid design in accordance with plans drawn up by James Ramsden.

Arts

Music

Barrow has produced several musical performers of note. They include Thomas Round, a singer and actor in D'Oyly Carte productions of Savoy Opera[147] as well as Glenn Cornick, the original bass guitarist in the rock band Jethro Tull.[148] Paul MacKenzie, bass player with 1980s Preston-based thrash metal band Xentrix, is from Barrow.[149] More recently, hip-hop DJ and record producer Aim has had considerable commercial success.[150]

Expressive arts

Several notables in Art and Literature have come from Barrow. Artist Keith Tyson, the 2002 Turner Prize winner, was born in nearby Ulverston, attended the Barrow-in-Furness College of Engineering and worked at the then VSEL shipyard.[151] Constance Spry, the author and florist who revolutionised interior design in the 1930s, and 1940s, moved to the town with her son Anthony during World War I to work as a welfare supervisor.[152] Peter Purves, later a Blue Peter presenter, began his acting career with 2 years as a member of the Renaissance Theatre Company at the town's Her Majesty's Theatre.[153]

During the mid-20th century, Barrow contained a wealth of theatres/cinemas including the Coliseum, Electric Theatre, Essoldo, Her Majesty's Theatre, Hippodrome, Pavilion, Ritz, Roxy, Royalty Theatre and Tivoli. All but the Pavilion and Roxy have since been demolished, most recently in 2004 with the demolition of the Apollo (formerly the Ritz). The Canteen Media & Arts Centre – known simply as "The Canteen" – and The Forum are now the main venues for theatre, while the Vue Cinema in Hollywood Park is the only cinema in the town.

Literature

In fictional works, Barrow and Vickerstown on Walney Island featured in children's show The Railway Series, which developed into Thomas the Tank Engine, as the point where the fictional Island of Sodor connected to mainland Britain and the national rail network.[154]

A number of the Lake Poets have referred to locations in present day Barrow, with one notable example being William Wordsworth's 1805 autobiographical poem The Prelude which describes his visits to Furness Abbey. The Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa wrote a series of sonnets called "Barrow-on-Furness" (sic). His "heteronym" Álvaro de Campos lived in Barrow when he was studying ship engineering, but Pessoa himself had never visited, and mistakenly assumed that "Furness" was the name of a river.[155] According to narrative exposition in Chapter five of Dorothy L. Sayers' 1926 novel Clouds of Witness, Inspector Charles Parker, Lord Peter Wimsey's friend and eventual brother-in-law, attended Barrow-in-Furness Grammar School. Renowned novelist D. H. Lawrence was in Barrow during the outbreak of World War I and wrote about his experiences in the town. The 2015 novel Career of Evil by J. K. Rowling's pseudonym Robert Galbraith was parially set in Barrow.[156]

Media

Newspapers

There is one paid-for evening daily paper, The Mail. There is also a weekly freesheet called the Advertiser, which is delivered to most households in the Furness area.

Radio

Barrow is served by one commercial radio station, Heart North West, which broadcasts from Manchester and serves the area around Morecambe Bay. Another commercial station, Abbey FM, ceased broadcasting in February 2009 when it went into administration.[157] The BBC's local radio service is BBC Radio Cumbria, who have studio facilities in the town.[158] Barrow and the Furness area is served by local community radio CANDOFM 106.3FM in the local area and also available online. With plans to expand further. CandoFM is located in Cooke Studios, Abbey Road, Barrow-in-Furness and run by 50+ volunteers providing local information as well as an eclectic mix of shows.

Television

Barrow lies in the Granada TV – North West England region with the main signal coming from the Winter Hill transmitter near Bolton. There is also a relay transmitter at Millom whose signal can be received in the northern end of the town.

Various television personalities were born in the district. Dave Myers was a biker born in Barrow, and found fame as one half of television cookery duo the Hairy Bikers.[159] Karen Taylor is a TV comedian best known for her BBC Three sketch show Touch Me, I'm Karen Taylor.[160] Steve Dixon is a newsreader for Sky News,[161] while Nigel Kneale was a well-known film and television scriptwriter.[162]

Wartime diarist and local housewife Nella Last's memoirs were adapted for television, with parts of the town used in filming. The resulting programme, Housewife, 49, written by and starring comedian Victoria Wood, was broadcast by ITV in 2006. It won two BAFTA awards – one for Best Single Drama, the other for Best Actress (Wood).[163][164] CITV children's show The Treacle People had two villains named Barrow and Furness.[165]

Dialect and accent

Furness is unique within Cumbria and the local dialect and accent is fairly Lancashire-orientated. Until 1974 Furness was an exclave of Lancashire, however as with Liverpool, for example, the Barrovian dialect has been influenced by large numbers of settlers from various regions. During the town's rapid growth from 1860 onward, thousands came to Barrow from Scotland, Ireland, Wales and elsewhere in northern England. As Glaswegian and Geordie dialects mingled in Barrow numerous more migrated from Lancashire and other parts of England which in effect created the noticeably Northern Barrovian dialect. In general the Barrovian accent tends to drop certain letters (including H and T).

Nightlife

There are many pubs and working men's clubs in Barrow. Barrow has fourteen of the latter, one of the highest number per capita of any British town.[166] There are also many bars and clubs found primarily in Barrow town centre on Duke Street and Cornwallis Street. Popular venues on Duke Street include the following bars: Jefferson's, the Buddha Bar, Bar Cairo and the Drawing Room. They did have a Yates's but the building was deemed unsafe and has since been demolished. Cornwallis Street – often dubbed the "Gaza Strip" by locals – is currently undergoing a multi-million pound renovation with the former Martini's being the flagship renovation into Club M. Other clubs on Cornwallis Street include: Kavanna's, O'Sullivan's and Skint. Between 2004 and 2010 Barrow was home to one of North West England's largest nightclubs, the 2,500-capacity Blue Lagoon occupied the entire hull of the former Danish ferry Princess Selandia, which has now left the town.[167] Barrow's largest nightclub is now Manhattans, which opened on Cavendish Street in late 2011.

Food

A traditional favourite food in Barrow is the pie, and particularly the meat and potato pie.[168] Pie shops are common, and Green's of Jarrow Street is noted as a favourite of Barrow-born celebrity chef Dave Myers [169] and journalist Martin Tarbuck, who declared them to be Britain's best pies in a book dedicated to the subject.[170]

Barrow was also the home of soft-drink company Marsh's, which produced a distinctive sarsaparilla-flavoured fizzy drink known as Sass.[171] Marsh's was purchased by Purity Soft Drinks of Birmingham in 1993, and the company stopped producing Sass in 1999. Remaining bottles have subsequently sold for high prices as a collector's item.[172] A new product, labelled "Barrow Sass", was launched in 2014 in a bid to replicate traditional Sass.[173] The coasts around Barrow have rich cockle beds from which cockles have traditionally been gathered, although numbers have been low following intensive gathering during the early 2000s, in the run-up to the 2004 Morecambe Bay cockling disaster.[174][175] One of England's few remaining Oyster farms can also be found located in the Biggar area of Walney. Traditional Cumberland sausages are less associated with Barrow itself than the rest of Cumbria, but are readily available from the surrounding rural area.[176] Cumbria has produced a number of famed dishes and is home to countless Michelin Guide restaurants, one of which is located in Dalton.

Social issues

Lifestyle

Having emerged as mixture of working-class cultures from across Britain and Ireland in the 19th century, subsequent low levels of migration and a continued tradition of industrial employment mean that Barrow's culture still reflects many of the traditions of the British working class.[177] In September 2008, Barrow was named as the most working-class location in the United Kingdom, based on a series of measures devised to judge the lifestyle of the people.[178] The research was carried out by Locallife.co.uk which determined that there is a fish and chip shop, working men's club, bookmakers or trade union office for every 2,917 people (Crewe, Doncaster, Wolverhampton and Preston completed the top five of 'the most working class places in Britain').[179] This is in direct contrast to the 1870s, when a developing Barrow had more aristocrats per head of the population than anywhere else in the country.[178]

In the 2015 Indices of Deprivation, Barrow was ranked as the 44th most deprived district in England (out of a total of 326).[180] The equivalent figures for 2007 and 2010 stood at 29th most deprived and 32nd most deprived respectively.[181] The Indices of Deprivation is based on income, employment, education, health, crime and barriers to housing and services and living environment. Within these subcategories, most notably Barrow ranked as the 5th most deprived in terms of health deprivation and disability, and in huge contrast, 324th most deprived in terms of access to housing and services (i.e. 3rd least deprived).[180] In the 2010 Indices of Deprivation, the majority of areas in Barrow Island, Central, Hindpool, Ormsgill were amongst the 3% most deprived areas in the country, while large parts of suburban Barrow including Newbarns and Roose were amongst the 25% of least deprived areas in England.[181]

Health

The principal hospital in Barrow is Furness General Hospital, operated by the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust and located on the outskirts of the town. As of July 2010 there were 12 NHS GP practices/doctors' surgeries and 5 NHS dental surgeries in Barrow.[182] The life expectancy for males in Barrow is 77.1 years (compared to the England average of 79.5) and 81.5 years for females (compared to the national average of 83.2).[183] A 2016 NHS in depth publication on health in Barrow indicated that the population of Barrow is by most measures in a worse state than the national average.[183] Indicators such as hospital stays for alcohol related harm, excessive weight, diabetes, smoking related death and self-harm are significantly worse than the England average. However, a number of indicators are similar to the average or are significantly better, including rates of homelesness, STI transmission and road deaths."[183] Barrow has the tenth worst rate of Incapacity Benefit claimants for mental illness in the country.

Crime

Policing is by Cumbria Constabulary, which alongside the county of Cumbria was formed in 1974. Previously the town was policed by Barrow-in-Furness Borough Police. Barrow previously had one full-time police station in Market Street in the Central ward. A new multi-million pound building was built on James Freel Close on Channelside in Hindpool and is the town's only police station, with extra jail cells and improved facilities. Several consecutive annual publications by Cumbria Constabulary entitled the 'Cumbria Community Safety Strategic Assessment' have stated that overall crime in Barrow is declining, with some indicators far better than the national average.[184] Despite this, crime levels as a whole are higher than the national average: 2013 statistics show crime levels in the borough as the 16th worst in the UK; most notably, Barrow has amongst the worst rates of alcohol misuse in the country.[185] Between July and December 2013 Barrow saw an average of 7.39 crimes per 100 of the population; the UK average was 6.57.[185] Incidents of anti-social behaviour stood at 7.83 per 100 in Barrow, cf 5.02 in the UK.[185] Burglary averaged 0.53 per 100 in 2013 while the national average was 1.00 per 100. Robbery averaged 0.02 in Barrow and 0.07 nationwide, shoplifting 0.72 and 0.53 and vehicle crime at 0.31 and 0.58.[185] Violent crimes and sexual offences occurred at a rate of 1.70 per 100, significantly higher than UK average of 1.06 and ranking the area as the 29th worst out of 348 in the country.[185] Crime rates remain the highest in deprived areas of inner wards such as Central and Hindpool.[184]

Since November 2019 Ministry of Defence Police have been based at the BAE Systems Shipyard.

Education

Education in the state-funded sector includes fifteen primary schools, five infant schools, five junior schools and many nurseries. The three secondary schools in the town are: Furness Academy, St. Bernard's Catholic High School and Walney School. Chetwynde School is an all-through school for children aged 4 to 18. Formerly an independent school, Chetwynde became a state-funded free school in 2014.

In the further education sector there is one college, Furness College. Furness College merged with Barrow Sixth Form College in 2016 forming the largest college in Cumbria.[186] Technical and professional qualifications are delivered at the Channelside campus, with A' levels delivered at the Rating Lane campus, the home of the former sixth form college. Although there is no higher education institution based in Barrow, Furness College offers several higher apprenticeships, foundation degrees, Bachelor's and Master's programmes accredited by the University of Cumbria, University of Lancaster and the University of Central Lancashire.[187]

The town's main library is the Central Library in Ramsden Square, situated near the town centre.[188] The library was established in 1882 in a room near the town hall, and moved to its current premises in 1922. A branch of the County Archive Service, opened in 1979 and containing many of the town's archives, is located within adjoining premises,[189] whilst until 1991 the library also housed the Furness Museum, a forerunner of the Dock Museum.[190] Smaller branch libraries are currently provided at Walney, Roose and Barrow Island. Known librarian Michael Wilson originates in Barrow-in-Furness. Michael Wilson is currently leader of the Collection Logistics Alpha Team at Cambridge University Library.[188]

See also

References

- Jenkins, Russell (22 December 2006). "Chocolate blog sends town into meltdown". The Times: 15.

- Barrow Steelworks Archived 19 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Appendix on unemployment as part of report into British Aerospace PLC proposed merger with VSEL" (PDF). Competition Commission. 23 May 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- [£1bn Walney offshore wind farm is world's largest https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-45424559 £1 billion Walney offshore wind farm is world's largest] BBC News, 6 September 2018. Accessed: 6 September 2018.

- Mills, David (1976). The Place Names of Lancashire. London: Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-3248-0.

- "Barrow-in-Furness: kept on life support by perpetual warfare".

- "most working class town – Google Search". www.google.com.

- Westcott, Lucy Townsend and Kathryn (17 July 2012). "Five lesser-spotted things in the census". BBC News.

- "Roman Treasure". Dock Museum. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Local history and heritage". Barrow Borough Council. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "Iron Mining". Industries of Cumbria. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- Raymond, Michael. "A Forgotten Medieval Powerhouse: Furness Abbey". New Histories Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- English Heritage. "Furness Abbey". English Heritage. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- "Plan of Barrow 1843" (PDF). Barrow Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "History of the Furness Railway Company". The Furness Railway Trust. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- Marshall, J.D. (1981) [1958]. Furness and the Industrial Revolution. Michael Moon, Beckermet, Cumbria. pp. 215–8. ISBN 978-0-904131-26-0.

- Richardson, Joseph (1870). Furness Past and Present. 1 of 2. pp. 18–24.

- "Barrow". Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- Bainbridge, TH (1939). "Barrow in Furness: A Population Study". Economic Geography. 15 (4): 379–383. doi:10.2307/141773. JSTOR 141773.

- "Timeline History of Barrow-in-Furness". VisitorUK. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Culture, Conflict, and Migration: The Irish in Victorian Cumbria. Liverpool University Press. 1998. ISBN 9780853236528. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- The Scots in Victorian and Edwardian Belfast: A Study in Elite Migration. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 9780748679928. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Barrow Flax and Jute Co". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- The Naval and Armaments Company Limited (1896). The Works at Barrow-in-Furness of The Naval Construction and Armaments Company Limited – Historical and Descriptive. Barrow-in-Furness: The Naval and Armaments Company Limited, partly reprinted from 'Engineering' magazine. p. 54.

- "Former Mayors". Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "History of Dalton-in-Furness". Dalton Online. Dalton Community Association. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- "Local History and Heritage". Barrow Borough Council. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- Partridge, Frank (16 March 2006). "The Complete Guide to: England's Islands". The Independent. London: Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- "Homepage". Abbey House Hotel. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Submarine History of Barrow-in-Furness". Submarine Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- Museums, Imperial War. "Barrow In Furness Cenotaph". Imperial War Museums.

- "The Battle of Britain – Diary – 2 September 1940". RAF. 16 February 2005. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- "World War II" (PDF). Dock Museum. 16 February 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- Freeman, TW (1966). The Conurbations of Great Britain (Second ed.). Manchester: The University Press. p. 239.

- "Project Corus (Workington) Steering Group Report". Northwest Development Agency. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original (DOC) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- "Barrow Steel". Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Maggie Mort; Graham Spinardi (2004). "Defence and the decline of UK mechanical engineering – the case of Vickers at Barrow". Business History. 46 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/00076790412331270099. S2CID 153992331.

- "Views of main parties as part of report into British Aerospace PLC proposed merger with VSEL" (PDF). Competition Commission. 23 May 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mort, Maggie (2002). Building the Trident Network. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13397-5.

- Schofield, Steven (January 2007). "Oceans of Work: Arms Conversion Revisited" (PDF). British American Security Information Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- "Legionnaires' source officially traced". BBC News. 20 August 2002. Archived from the original on 14 August 2003. Retrieved 21 July 2003.

- "A Total Shambles". North West Evening Mail. 12 June 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Bug Death Council Worker Cleared". BBC News. 31 July 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Back in the Line of Fire". publicfinance.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Coronavirus: Why does Cumbrian town of Barrow-in-Furness have highest rate of infection in UK?". The Independent. Retrieved 5 June 2020.