The Railway Series

The Railway Series is a set of British story books about a railway system located on the fictional Island of Sodor. There are 42 books in the series, the first being published in 1945. Twenty-six were written by the Rev. Wilbert Awdry, up to 1972. A further 16 were written by his son, Christopher Awdry; 14 between 1983 and 1996, and two more in 2007 and 2011.

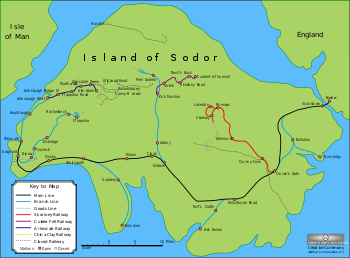

Map showing the railways on the fictional Island of Sodor | |

| Author |

|

|---|---|

| Illustrator |

|

| Cover artist | (see illustrators above) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's |

| Publisher |

|

Publication date |

|

Published in English |

|

Nearly all of The Railway Series stories were based upon real-life events. As a lifelong railway enthusiast, Awdry was keen that his stories should be as realistic as possible. The engine characters were almost all based upon real classes of locomotive, and some of the railways themselves were directly based upon real lines in the British Isles.

Characters and stories from the books formed the basis of the children's television series Thomas & Friends. Audio adaptations of The Railway Series have been recorded at various times under the title The Railway Stories.

Origins

The stories began in 1942, when two-year-old Christopher Awdry had caught measles and was confined to a darkened room. His father would tell him stories and rhymes to cheer him up. One of Christopher's favourite rhymes was:[1]

Early in the morning,

Down at the station,

All the little engines

Standing in a row.

Along comes the driver,

Pulls the little lever

Puff, puff! Chuff, chuff!

Off we go!

The precise origins of this rhyme are unknown, but research by Brian Sibley suggests that it originated at some point prior to the First World War.[1] Wilbert Awdry's answers to Christopher's questions about the rhyme led to the creation of a short story, "Edward's Day Out". This told the story of Edward the Blue Engine, an old engine who is allowed out of the shed for a day. Another story about Edward followed, which this time also featured a character called Gordon the Big Engine, named after a child living on the same road who Christopher considered rather bossy.[2]

A third story had its origins in a limerick of which Christopher was fond,[3] and which Awdry used to introduce The Sad Story of Henry:[4]

Once, an engine attached to a train

Was afraid of a few drops of rain

It went into a tunnel,

And squeaked through its funnel

And never came out again.

As with the previous rhyme, the origins of this are uncertain, but Awdry received a letter telling him that a similar poem had appeared in a book of children's rhymes, published in 1902:[3]

Once an engine when fixed to a train

Was alarmed at a few drops of rain,

So went "puff" from its funnel

Then fled to a tunnel,

And would not come out again.

This story introduced the popular characters Henry the Green Engine and the Fat Director. Encouraged by Margaret, his wife, Awdry submitted the three stories to Edmund Ward for publication in 1943. The head of the children's books division requested a fourth story to bring the three engines together and redeem Henry, who had been bricked up in a tunnel in the previous story. Although Wilbert had not intended that the three engines live on the same railway, he complied with the request in the story Edward, Gordon and Henry. The four stories were published in 1945 as a single volume, The Three Railway Engines, illustrated by William Middleton.

Christmas 1942 saw the genesis of the character that grew to become the most famous fictional locomotive in the world. Awdry constructed a toy tank engine for Christopher, which gained the name Thomas. Stories about Thomas were requested by Christopher, and 1946 saw the publication of Thomas the Tank Engine. This was illustrated by Reginald Payne, whom Wilbert felt to be a great improvement over Middleton. Like its predecessor, this book was a success and Awdry was asked to write stories about James, a character who first appeared in Thomas and the Breakdown Train, the final story in Thomas the Tank Engine. The book James the Red Engine appeared in 1948, the year in which the railways in Britain were nationalised, and from this point onwards the Fat Director was known by his familiar title of the Fat Controller.

James the Red Engine was notable as the first book to be illustrated by C. Reginald Dalby, perhaps the most famous of the Railway Series artists, and certainly the most controversial due to the criticism later aimed at him by Awdry. Dalby illustrated every volume up to Percy the Small Engine (1956), and also produced new illustrations for The Three Railway Engines and made changes to those of Thomas the Tank Engine.

Successive books would introduce such popular characters as Annie and Clarabel, Percy the Small Engine and Toby the Tram Engine.

In making the stories as real as possible, Awdry took a lot of inspiration from a number of sources in his extensive library, and found the Railway Gazette's "Scrapheap" column particularly useful as a source of unusual railway incidents that were recreated for The Railway Series characters.

Awdry continued working on The Railway Series until 1972, when Tramway Engines (book 26 in the series) was published. However, he had been finding it increasingly difficult to come up with ideas for new stories, and after this he felt that "the well had run dry" and so decided that the time had come to retire. He wrote no further Railway Series volumes, but later wrote a spin-off story for the television series Thomas's Christmas Party and expanded versions of some of his earlier stories, as well as writing The Island of Sodor: Its People, History and Railways. In addition, he wrote a number of short stories and articles for Thomas the Tank Engine Annuals.[5]

Cultural context

Anthropomorphization of locomotives has a literary tradition extending back at least as far as the writings of Rudyard Kipling in his 1897 story ".007".[6]

Continuing series under Christopher Awdry

Christopher Awdry, for whom the stories were first devised, continued writing the stories almost by accident. He was a keen railway enthusiast like his father, and it was on a visit to the Nene Valley Railway that he received the inspiration for his first story. A railwayman's account of a locomotive running out of steam short of its destination became Triple Header, a story in which Thomas, Percy and Duck take on Gordon's Express but find it more than they can handle. Christopher devised three other stories, Stop Thief!, Mind That Bike and Fish.

He showed them to his father, who suggested that he submit them for publication, with his blessing. At the time, work on the television adaptation was underway, and so Kaye and Ward (then publishers of the series) were willing to revive The Railway Series. The book Really Useful Engines was published in 1983. By coincidence, W. Awdry had considered this as a title for his own 27th volume before abandoning the project.

Thirteen more books followed, including the series' 50th anniversary volume, Thomas and the Fat Controller's Engines. A number of stories were also written for the television series, most notably More About Thomas the Tank Engine, The Railway Series' 30th volume.

However, Christopher Awdry found himself increasingly coming into conflict with his publishers, which ironically arose through the success of the television series. The television series had made Thomas its central character, and therefore the most well-known of the engines. Consequently, the publishers were increasingly demanding stories that would focus on Thomas at the expense of other characters. As a compromise, volumes appeared that were named after Thomas but did not actually focus upon him. Thomas and the Fat Controller's Engines featured only one story about Thomas and Thomas Comes Home did not feature Thomas until the last page.

The series' 40th volume, New Little Engine, appeared in 1996. The then-publisher, Egmont, expressed no further interest in publishing new Railway Series books and allowed the existing back catalogue to go out of print.

Despite this, in 2005 Christopher's own publishing company, Sodor Enterprises, published a book entitled Sodor: Reading Between the Lines. This volume expanded the fictional world of Sodor up to the present day and dealt with many of the factual aspects of the series. With this publishing company he also wrote several railway-based children's books, most of which were set on real railways in Britain. He continues to promote the original stories and to participate in Railway Series-related events.

In 2006, the publishers reviewed their policy and started to re-introduce the books in their original format. After many years of being unavailable, the fourteen books written by Christopher were also re-released, early in August 2007.

On 3 September 2007, Christopher published a new book, Thomas and Victoria, extending the series to 41 volumes. It is illustrated by Clive Spong. The book addresses issues relating to the railway preservation movement.

Series conclusion

For many years, many of the books in The Railway Series were unavailable to buy in their original format, and the publishers would not publish any new stories. There was a selected print run in 2004 consisting of just the original 26 books, but by 2005, the sixtieth anniversary, there was still disappointment from the Awdry family that all of the stories were not being published in their original format.[7] In August 2007, Christopher Awdry's first fourteen books were reissued, and number 41, Thomas and Victoria was released the following month. An omnibus edition of Christopher Awdry's books including book 41, The New Collection, was released at the same time. In July 2011, Egmont Books UK released another Railway Series book, no. 42 in the series entitled Thomas and his Friends. The final story ended with the words "The End".[5]

Christopher Awdry said that he had other material, which he hoped would be published. He narrated new stories about the narrow gauge engines on 'Duncan Days' at the Talyllyn Railway in Wales, but there is no indication that these will be published. His 2005 book Sodor: Reading Between the Lines updated readers on developments since 1996.

Illustrators

The Railway Series is perhaps as highly regarded for its illustrations as for its writing, which in the immediate post-Second World War era were seen as uniquely vivid and colourful. Indeed, some critics (notably Miles Kington) have claimed that the quality of the illustrations outshines that of the writing.

The first edition of The Three Railway Engines was illustrated by the artist William Middleton, with whom Awdry was deeply dissatisfied. The second artist to work on the series was Reginald Payne, who illustrated Thomas the Tank Engine in a far more realistic style. Despite an early disagreement as to how Thomas should look, Awdry was ultimately pleased with the pictures produced.

Payne proved impossible to contact to illustrate James the Red Engine – he had suffered from a nervous breakdown – and so C. Reginald Dalby was hired. Dalby also illustrated the next eight books in the series. The Three Railway Engines was reprinted with Dalby's artwork replacing William Middleton's and Dalby also touched up Payne's artwork in the second book. Dalby's work on the series proved popular with readers, but not with the author, who repeatedly clashed with him over issues of accuracy and consistency. Dalby resigned from the series in 1956, following an argument over the portrayal of Percy the Small Engine in the book of the same name.[8] Awdry had built a model of Percy as a reference for the artist but Dalby did not make use of it. Despite the tempestuous relationship with Awdry, Dalby is probably the best remembered of the series' artists.

With The Eight Famous Engines (1957), John T. Kenney took over the illustration of the series. His style was less colourful but more realistic than Dalby's. Kenney made use of Awdry's model engines as a reference. As a result of his commitment to realism and technical accuracy, he enjoyed a far more comfortable working relationship with Awdry, which lasted until Gallant Old Engine (1962), when Kenney's eyesight began to fail him.

The artist initially chosen to replace him was the Swedish artist Gunvor Edwards. She began illustrating Stepney the "Bluebell" Engine, but felt unsuited to the work. She was assisted for that volume by her husband Peter, who effectively took over from then on. Both artists retained credit for the work, and the "Edwards era" lasted until Wilbert Awdry's last volume, Tramway Engines. The style used in these volumes was still essentially realistic, but had something of an impressionistic feel.

When Christopher Awdry took over as author of the series in 1983, the publisher was keen to find an illustrator who would provide work that had the gem-like appeal of Dalby's pictures, but also had the realism of Kenney and Edwards' artwork. The artist chosen was Clive Spong. He illustrated all of Christopher Awdry's books, a greater number than any other artist working on The Railway Series. He also produced illustrations for a number of spin-off stories written by the Awdrys, and his artwork was used in The Island of Sodor: Its People, History and Railways.

Format and presentation

The books were produced in an unusual landscape format. Each one was around 60 pages long, 30 of which would be text and 30 illustrations. The books were each divided into four stories (with the exception of Henry the Green Engine, which was divided into five).

Each book from Thomas the Tank Engine onwards opened with a foreword. This would act as a brief introduction to the book, its characters or its themes. They were written as a letter, usually to the readers (addressed as "Dear Friends") but sometimes to individual children who had played some part in the story's creation. The foreword to Thomas the Tank Engine was a letter to Christopher Awdry. This section would often advertise real railways or acknowledge the assistance of people or organisations. The foreword to The Little Old Engine is unique in acknowledging the fact that Skarloey (and, by implication, the entirety of The Railway Series) is fictional.

The unusual shape of the books made them instantly recognisable. However, it did prompt complaints from booksellers that they were difficult to display, and even that they could easily be shoplifted. Nonetheless, the format was imitated by publishers Ian Allan for their Sammy the Shunter and Chuffalong books.

Unusually for children's books of the austerity period, The Railway Series was printed in full colour from the start, which is cited by many critics as one of its major selling points in the early days.

Sodor

The Rev. W. Awdry received numerous letters from young fans asking questions about the engines and their railway, as well as letters concerning inconsistencies within the stories. In an effort to answer these, he began to develop a specific setting for the books. On a visit to the Isle of Man, he discovered that the bishop there is known as the Bishop of Sodor and Man. The "Sodor" part of the title comes from the Sudreys, but Awdry decided that a fictional island between the Isle of Man and England by that name would be an ideal setting for his stories.

In partnership with his brother George (the librarian of the National Liberal Club), he gradually devised Sodor's history, geography, language, industries and even geology. The results were published in the book The Island of Sodor: Its People, History and Railways in 1987.

Cameo appearances

The Awdrys both wrote about Sodor as if it were a real place that they visited, and that the stories were obtained first-hand from the engines and Controllers. This was often "documented" in the foreword to each book. However, in some of the W. Awdry's later books, he made appearances as an actual character. The character was known as the Thin Clergyman and was described as a writer, though his real name and connections to the series were never made explicit.

He was invariably accompanied by the Fat Clergyman, the Rev. "Teddy" Boston,[9] who was a fellow railway enthusiast and close friend. The two Clergymen were portrayed as railway enthusiasts, and were responsible for annoying the Small Engines and discovering Duke the Lost Engine. They were often figures of fun, liable to be splashed with water or to fall through a roof.

Awdry also appeared in a number of illustrations, usually as a joke on the part of the illustrator. In one illustration by John T. Kenney in Duck and the Diesel Engine he appears with a figure who bears a strong resemblance to C. Reginald Dalby, which Brian Sibley has suggested might be a dig at Dalby's inaccurate rendition of the character of Duck.

A vicar appears in Edward the Blue Engine and other volumes as the owner of Trevor the Traction Engine. This may be a reference to Teddy Boston, who had himself saved a traction engine from scrap.

C. Reginald Dalby illustrated the entire Awdry family – Wilbert, Margaret, Christopher, Veronica and Hilary – watching Percy pass through a station ("Percy runs away" in Troublesome Engines (p53)).[10] Otherwise, Christopher Awdry never appeared in the books, but would often describe meetings with the engines in the book forewords, usually with some degree of humour.

Other people associated with The Railway Series were also referenced. In Dalby's books, he made allusions to himself twice on store signs (Seen in Off the Rails and Saved from Scrap) and a reference to E.T.L. Marriott, who edited The Railway Series, in Percy Takes the Plunge on a "Ship Chandlers" company sign. Peter Edwards also notes that he based Gordon's face on Eric Marriot's.

The Fat Controller (originally The Fat Director in the earliest books which pre-dated the nationalisation of Britain's railways in 1948) was a fictional character, although Mr Gerard Fiennes, one of the highest-regarded managers on British Railways, published his autobiography "I tried to run a Railway" on his retirement in 1968, and says that he originally wanted to call the book "The Fat Controller" but the publishers would not permit this.

The Thin Controller, in charge of the narrow-gauge trains in the books which are based on the Talyllyn Railway in Wales, was based on Mr Edward Thomas, the manager of the Talyllyn Railway in its last years before enthusiasts took it over in 1951.

A number of the stories are based on articles (often quite brief mentions) which appeared in railway enthusiast publications of the period. There were very few of these publications compared to modern times, but the monthly Railway Magazine was a long-running enthusiasts' companion and the origins of several stories can be recognised, as also the railway books and histories written by Mr Hamilton Ellis, one of the early railway book writers.

British Railways: The Other Railway

Developments on British Railways were often mirrored, satirised and even attacked in The Railway Series. The book Troublesome Engines (1950), for example, dealt with industrial disputes on British Railways. As the series went on, comparisons with the real railways of Britain became more explicit, with engines and locations of British Railways (always known as "The Other Railway") making appearances in major or cameo roles.

The most obvious theme relating to British Railways was the decline of steam locomotion and its replacement with diesels. The first real instance of this was in the book Duck and the Diesel Engine (1958) in which an unpleasant diesel shunter arrives, causes trouble and is sent away. This theme may have been visited again in The Twin Engines (1960), in which an engine is ordered from Scotland, and two arrive, implying the other went to Sodor with his brother to avoid being scrapped. The 1963 volume Stepney the "Bluebell" Engine explained that steam engines were actually being scrapped to make way for these diesels, and again featured a diesel getting his comeuppance. The book Enterprising Engines was published in 1968, the year when steam finally disappeared from British Railways, and was the most aggressive towards dieselisation and Dr Beeching's modernisation plan. It features yet another arrogant diesel who is sent away, an additional one who stays on the Island of Sodor, a visit by the real Flying Scotsman locomotive, a steam engine, Oliver, making a daring escape to Sodor, and Sir Topham Hatt making a declaration that the steam engines of his railway will still be in service.

Thereafter, the books were less critical towards BR. Indeed, by the time of Christopher Awdry's 1984 book James and the Diesel Engines, the series was acknowledging that diesels could, in fact, be useful.

Preservation movement

W. Awdry used the books to promote steam railways in the UK. The first instance of this was the creation of the Skarloey Railway, a railway on Sodor that closely resembled the Talyllyn Railway in Wales, of which W. Awdry was a member. Books focusing on this railway would include a promotion for the Talyllyn Railway, either in the stories themselves, in a footnote or in the foreword. Many illustrations in the books depict recognisable locations on the Talyllyn Railway, and various incidents and mishaps recorded by Tom Rolt in his book Railway Adventure are also recognisable in their adaptations for the Skarloey Railway stories.

From the 1980s onwards, this association was carried further, with the Awdrys permitting the Talyllyn Railway to repaint one of their engines in the guise of its Sodor "twin". The first engine to receive this treatment was their No. 3, Sir Haydn, which was repainted to resemble the character Sir Handel. The second was No. 4, Edward Thomas, which became Peter Sam. In 2006 No. 6, Douglas runs in the guise of Duncan. As well as paint schemes and names taken from the books' artwork, these locomotives are fitted with fibreglass "faces" taken from the books as well, which delight children but dismay locomotive enthusiast purists. These characters' appearances have been written into The Railway Series' continuity by Christopher Awdry in the form of visits by the fictional engines to the Talyllyn Railway.

Two other railways on Sodor are directly based on real railways. The Culdee Fell Railway (usually known as the Mountain Railway) is based on the Snowdon Mountain Railway, also in Wales. The Arlesdale Railway is based on the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway in Cumbria. Some other lines on Sodor are heavily inspired by real lines. For example, the Mid Sodor Railway acknowledges the Ffestiniog and Corris Railway and the Little Western bears a resemblance to the South Devon Railway.

From Duck and the Diesel Engine onwards, a number of real engines and railways were explicitly featured. The characters of Flying Scotsman, City of Truro, Stepney and Wilbert were all real locomotives that made significant appearances in The Railway Series, the latter two having entire volumes dedicated to them, Stepney the "Bluebell" Engine and Wilbert the Forest Engine. Wilbert's appearance was of particular significance. The locomotive in question was named in tribute to W. Awdry, the president of the Dean Forest Railway at the time. Christopher Awdry wrote Wilbert the Forest Engine in gratitude.

Thomas and the Great Railway Show (1991) featured a visit by Thomas to the National Railway Museum in York, along with appearances by several of the real locomotives living there. At the end of this book, Thomas is made an honorary member of the National Collection. This was mirrored by the real life inclusion of The Railway Series in the National Railway Museum's extensive library of railway books in recognition of their influence on railway preservation.

Thomas and Victoria (2007) focuses on the rescue and restoration of a coach. Victoria had been used as a summerhouse in an orchard by the railway, but was rescued by the Fat Controller who then sent her to the works at Crovan's Gate to be restored. She then became part of the vintage train, working with Toby and Henrietta. The formation of a vintage train is based on the activities by the Furness Railway Trust,[11] but coach restoration is common on heritage railways.

Characters

The series has featured numerous characters, both railway-based and otherwise. Some of the more notable ones are:

- Thomas the Tank Engine

- Edward the Blue Engine

- Henry the Green Engine

- Gordon the Big Engine

- James the Red Engine

- Percy the Small Engine

- Toby the Tram Engine

- Duck the Great Western Engine

- Donald and Douglas

- Oliver the Western Engine

- Trevor the Traction Engine

- Annie and Clarabel, Thomas's coaches

- Bertie the Bus

- Terence the Tractor

- Harold the Helicopter

- The Fat Controller

Books

The following table lists the titles of all 42 books in The Railway Series.

| Author | Volume | Title | Publication | Characters' first appearance | Illustrator | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rev. W. Awdry | 1 | The Three Railway Engines | May 1945 | Edward · Gordon · Henry · Fat Director (later renamed "The Fat Controller" (also known as "Sir Topham Hatt") starting in James the Red Engine) | William Middleton (later completely redrawn by C. Reginald Dalby) | Edmund Ward, Ltd. |

| 2 | Thomas the Tank Engine | March 1946 | Thomas · James · Annie and Clarabel | Reginald Payne (later partially redrawn by C. Reginald Dalby) | ||

| 3 | James the Red Engine | April 1948 | C. Reginald Dalby | |||

| 4 | Tank Engine Thomas Again | September 1949 | Terence · Bertie | |||

| 5 | Troublesome Engines | January 1950 | Percy | |||

| 6 | Henry the Green Engine | June 1951 | ||||

| 7 | Toby the Tram Engine | April 1952 | Toby · Henrietta | |||

| 8 | Gordon the Big Engine | December 1953 | ||||

| 9 | Edward the Blue Engine | February 1954 | Trevor | |||

| 10 | Four Little Engines | October 1955 | Skarloey · Rheneas · Sir Handel · Peter Sam · Thin Controller · The Owner · Carriages: Agnes, Ruth, Lucy, Jemima, Beatrice · Mrs Last | |||

| 11 | Percy the Small Engine | September 1956 | Duck · Harold | |||

| 12 | The Eight Famous Engines | November 1957 | The Foreign Engine · Jinty and Pug | John T. Kenney | ||

| 13 | Duck and the Diesel Engine | August 1958 | City of Truro · Diesel | |||

| 14 | The Little Old Engine | July 1959 | Rusty · Duncan · Carriages: Cora, Ada, Jane, Mabel, Gertrude, Millicent | |||

| 15 | The Twin Engines | September 1960 | Donald and Douglas · Spiteful Brake Van | |||

| 16 | Branch Line Engines | November 1961 | Daisy | |||

| 17 | Gallant Old Engine | December 1962 | George the Steamroller · Nancy the Guard's Daughter | |||

| 18 | Stepney the "Bluebell" Engine | November 1963 | Stepney · Caroline the car · The Diesel/D4711 | Peter and Gunvor Edwards | ||

| 19 | Mountain Engines | August 1964 | Culdee · Ernest · Wilfred · Godred · Lord Harry · Alaric · Eric · Catherine · The Truck · Lord Harry Barrane · Mr Walter Richards | |||

| 20 | Very Old Engines | April 1965 | Neil | |||

| 21 | Main Line Engines | September 1966 | BoCo · Bill and Ben | |||

| 22 | Small Railway Engines | September 1967 | Mike · Rex · Bert · Ballast Spreader · The Small Controller |

Kaye & Ward, Ltd. Edmund Ward, Ltd. | ||

| 23 | Enterprising Engines | October 1968 | Flying Scotsman · D199 · Bear · Oliver · Toad the Brake Van · Coaches: Isabel, Dulcie, Alice, Mirabel | |||

| 24 | Oliver the Western Engine | November 1969 | S.C.Ruffey · Bulgy | Kaye & Ward, Ltd. | ||

| 25 | Duke the Lost Engine | October 1970 | Duke · Falcon · Stuart · Stanley | |||

| 26 | Tramway Engines | October 1972 | Mavis | |||

| Christopher Awdry | 27 | Really Useful Engines | September 1983 | Tom Tipper | Clive Spong | |

| 28 | James and the Diesel Engines | September 1984 | Old Stuck-up · The Works Diesel | Kaye & Ward, Ltd. William Heinemann | ||

| 29 | Great Little Engines | October 1985 | ||||

| 30 | More About Thomas the Tank Engine | September 1986 | ||||

| 31 | Gordon the High-Speed Engine | September 1987 | Pip & Emma | |||

| 32 | Toby, Trucks and Trouble | September 1988 | The Old Engine · Bulstrode | |||

| 33 | Thomas and the Twins | September 1989 | ||||

| 34 | Jock the New Engine | August 1990 | Arlesdale Railway engines: Frank · Jock | |||

| 35 | Thomas and the Great Railway Show | August 1991 | Engines at the National Railway Museum | |||

| 36 | Thomas Comes Home | June 1992 | ||||

| 37 | Henry and the Express | April 1993 | ||||

| 38 | Wilbert the Forest Engine | August 1994 | Wilbert · Sixteen | |||

| 39 | Thomas and the Fat Controller's Engines | August 1995 | ||||

| 40 | New Little Engine | August 1996 | Fred · Kathy & Lizzie (cleaners) · Ivo Hugh | |||

| 41 | Thomas and Victoria | September 2007 | Victoria (a coach) · Helena (a coach similar to Victoria) · Albert | Egmont Publishing | ||

| 42 | Thomas and his Friends | July 2011 |

References in popular culture

Satirical magazine Private Eye produced a book Thomas the Privatised Tank Engine, written in the style of The Railway Series. The stories were strongly critical of private railway companies and the Government of John Major, and covered subjects such as the Channel Tunnel, London Underground, transport of radioactive waste and the perceived dangerous state of the railways.

Andrew Lloyd Webber wanted to produce a musical based on The Railway Series, but Awdry refused to give him the control he wanted. Lloyd Webber would go on to compose Starlight Express, and create The Really Useful Group, a name inspired by the catchphrase "Really Useful Engines".

Notes

- Sibley, p. 96

- Sibley, p. 98

- Sibley, pp. 99–100

- Rev. W. Awdry (1945). The Three Railway Engines. Edmund Ward. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-434-92778-3.

- Kagachi, Chihiro (2014). Christopher Awdry: A Biography.

- Wilson. ".007".

- Mansfield, Susan (6 May 2005). "Steaming Ahead for Six Decades". The Scotsman. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- "The Artists of The Railway Series". Sodor Island - A Thomas Fan Site. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- "Teddy Boston - the Fat Clergyman".

- Sibley, p. 150

- "The Furness Railway Company". www.furnessrailwaytrust.org.uk.

References

- Sibley, Brian (1995). The Thomas the Tank Engine Man. Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-96909-5.

- Wilson, Alastair. ".007". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Railway Series |

- List of The Railway Series books at the Wayback Machine (archived February 2, 2007) (in Portable Document Format).

- The Real Lives of Thomas the Tank Engine - documents real influences behind the series

- Awdry Family Website at the Wayback Machine (archived April 17, 2008) – Formerly www.awdry.family.name (Dead link discovered April 2010)

- Sodor Enterprises (publishing company) at the Wayback Machine (archived December 22, 2007) – Formerly www.sodor.co.uk (Dead link discovered April 2010)