Paul Verlaine

Paul-Marie Verlaine (/vɛərˈlɛn/;[1] French: [vɛʁlɛn(ə)]; 30 March 1844 – 8 January 1896) was a French poet associated with the Symbolist movement and the Decadent movement. He is considered one of the greatest representatives of the fin de siècle in international and French poetry.

Paul Verlaine | |

|---|---|

Paul Verlaine | |

| Born | 30 March 1844 Metz, France |

| Died | 8 January 1896 (aged 51) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Genre | Decadent, Symbolist |

| Signature |  |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Biography

Early life

Born in Metz, Verlaine was educated at the Lycée Impérial Bonaparte (now the Lycée Condorcet) in Paris and then took up a post in the civil service. He began writing poetry at an early age, and was initially influenced by the Parnassien movement and its leader, Leconte de Lisle. Verlaine's first published poem was published in 1863 in La Revue du progrès, a publication founded by poet Louis-Xavier de Ricard. Verlaine was a frequenter of the salon of the Marquise de Ricard[2] (Louis-Xavier de Ricard's mother) at 10 Boulevard des Batignolles and other social venues, where he rubbed shoulders with prominent artistic figures of the day: Anatole France, Emmanuel Chabrier, inventor-poet and humorist Charles Cros, the cynical anti-bourgeois idealist Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Théodore de Banville, François Coppée, Jose-Maria de Heredia, Leconte de Lisle, Catulle Mendes and others. Verlaine's first published collection, Poèmes saturniens (1866),[3] though adversely commented upon by Sainte-Beuve, established him as a poet of promise and originality.

Marriage and military service

Mathilde Mauté became Verlaine's wife in 1870. At the proclamation of the Third Republic in the same year, Verlaine joined the 160th battalion of the Garde nationale, turning Communard on 18 March 1871.

He became head of the press bureau of the Central Committee of the Paris Commune. Verlaine escaped the deadly street fighting known as the Bloody Week, or Semaine Sanglante, and went into hiding in the Pas-de-Calais.

Relationships with Rimbaud and Létinois

Verlaine returned to Paris in August 1871, and, in September, he received the first letter from Arthur Rimbaud, who admired his poetry. He urged Rimbaud to come to Paris, and by 1872, he had lost interest in Mathilde, and effectively abandoned her and their son, preferring the company of his new lover.[3] Rimbaud and Verlaine's stormy affair took them to London in 1872. In Brussels in July 1873 in a drunken, jealous rage, he fired two shots with a pistol at Rimbaud, wounding his left wrist, though not seriously injuring the poet. As an indirect result of this incident, Verlaine was arrested and imprisoned at Mons[4], where he underwent a re-conversion to Roman Catholicism, which again influenced his work and provoked Rimbaud's sharp criticism.[5]

The poems collected in Romances sans paroles (1874) were written between 1872 and 1873, inspired by Verlaine's nostalgically colored recollections of his life with Mathilde on the one hand and impressionistic sketches of his on-again off-again year-long escapade with Rimbaud on the other. Romances sans paroles was published while Verlaine was imprisoned. Following his release from prison, Verlaine again traveled to England, where he worked for some years as a teacher, teaching French, Latin and Greek, and drawing at a grammar school in Stickney in Lincolnshire.[6] From there he went to teach in nearby Boston, before moving to Bournemouth.[7] While in England he produced another successful collection, Sagesse. He returned to France in 1877 and, while teaching English at a school in Rethel, fell in love with one of his pupils, Lucien Létinois, who inspired Verlaine to write further poems.[8] Verlaine was devastated when Létinois died of typhus in 1883.

Final years

Verlaine's last years saw his descent into drug addiction, alcoholism, and poverty. He lived in slums and public hospitals, and spent his days drinking absinthe in Paris cafés. However, the people's love for his art was able to resurrect support and bring in an income for Verlaine: his early poetry was rediscovered, his lifestyle and strange behaviour in front of crowds attracted admiration, and in 1894 he was elected France's "Prince of Poets" by his peers.

His poetry was admired and recognized as ground-breaking, and served as a source of inspiration to composers. Gabriel Fauré composed many mélodies, such as the song cycles Cinq mélodies "de Venise" and La bonne chanson, which were settings of Verlaine's poems.[9] Claude Debussy set to music Clair de lune and six of the Fêtes galantes poems, forming part of the mélodie collection known as the Recueil Vasnier; he also made another setting of Clair de lune, and the poem inspired his Suite bergamasque.[10] Reynaldo Hahn set several of Verlaine's poems as did the Belgian-British composer Poldowski (daughter of Henryk Wieniawski).

His drug dependence and alcoholism caught up with him and took a toll on his life. Paul Verlaine died in Paris at the age of 51 on 8 January 1896; he was buried in the Cimetière des Batignolles (he was first buried in the 20th division, but his grave was moved to the 11th division—on the roundabout, a much better location—when the Boulevard Périphérique was built).[11]

Style

Much of the French poetry produced during the fin de siècle was characterized as "decadent" for its lurid content or moral vision. In a similar vein, Verlaine used the expression poète maudit ("cursed poet") in 1884 to refer to a number of poets like Stéphane Mallarmé, Arthur Rimbaud, Aloysius Bertrand, Comte de Lautréamont, Tristan Corbière or Alice de Chambrier, who had fought against poetic conventions and suffered social rebuke or were ignored by the critics. But with the publication of Jean Moréas' Symbolist Manifesto in 1886, it was the term symbolism which was most often applied to the new literary environment. Along with Verlaine, Mallarmé, Rimbaud, Paul Valéry, Albert Samain and many others began to be referred to as "Symbolists." These poets would often share themes that parallel Schopenhauer's aesthetics and notions of will, fatality and unconscious forces, and used themes of sex (such as prostitutes), the city, irrational phenomena (delirium, dreams, narcotics, alcohol), and sometimes a vaguely medieval setting.

In poetry, the symbolist procedure—as typified by Verlaine—was to use subtle suggestion instead of precise statement (rhetoric was banned) and to evoke moods and feelings through the magic of words and repeated sounds and the cadence of verse (musicality) and metrical innovation.

Verlaine described his typically decadent style in great detail in his poem "Art Poétique," describing the primacy of musicality and the importance of elusiveness and "the Odd." He spoke of veils and nuance and implored poets to "Keep away from the murderous Sharp Saying, Cruel Wit, and Impure Laugh." It is with these lyrical veils in mind that he concluded by suggesting that a poem should be a "happy occurrence."[12]

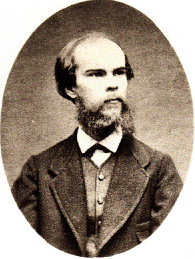

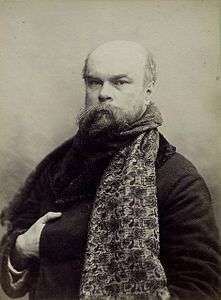

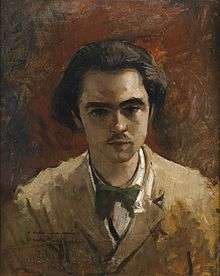

Portraits

Numerous artists painted Verlaine's portrait. Among the most illustrious were Henri Fantin-Latour, Antonio de la Gándara, Eugène Carrière, Gustave Courbet, Frédéric Cazalis, and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen.

by Frédéric Bazille

1867

by Eugène Carrière

1890

by Edmond Aman-Jean

1892

by Isaac Israëls

1892

by Edouard Chantalat

1898

Posthumous,

from a photograph.

Historical footnote

- In preparation for Operation Overlord, the BBC via Radio Londres had signaled to the French Resistance that the opening lines of the 1866 Verlaine poem "Chanson d'automne" were to indicate the start of D-Day operations. The first three lines of the poem, "Les sanglots longs / Des violons / De l'automne" ("Long sobs of autumn violins"), meant that Operation Overlord was to start within two weeks. These lines were broadcast on 1 June 1944. The next set of lines, "Blessent mon coeur / D'une langueur / Monotone" ("wound my heart with a monotonous languor"),[13] meant that it would start within 48 hours and that the resistance should begin sabotage operations especially on the French railroad system; these lines were broadcast on 5 June at 23:15.[14][15][16]

In popular culture

- Among the admirers of Verlaine's work was the Russian language poet and novelist Boris Pasternak. Pasternak went so far as to translate much of Verlaine's verse into Russian. According to Pasternak's mistress and muse, Olga Ivinskaya,

Whenever [Boris Leonidovich] was provided with literal versions of things which echoed his own thoughts or feelings, it made all the difference and he worked feverishly, turning them into masterpieces. I remember his translating Paul Verlaine in a burst of enthusiasm like this -- L'Art poétique was after all an expression of his own beliefs about poetry.[17]

- In 1943, Richard Hillary, author of The Last Enemy, quoted Verlaine (Sagesse) in his poem. [18]

- In 1964, French singer Léo Ferré set to music fourteen poems from Verlaine and some from Rimbaud for his album Verlaine et Rimbaud. He also sang two other poems (Colloque sentimental, Si tu ne mourus pas) in his album On n'est pas sérieux quand on a dix-sept ans (1987).

- Soviet/Russian composer David Tukhmanov has set Verlaine's poem to music in Russian and French (cult album On a Wave of My Memory, 1975).[19]

- Guitarist, singer and songwriter Tom Miller (better known as Tom Verlaine, leader of the art rock band Television) chose his stage name as a tribute to Verlaine.

- New Zealand indie rock band The Verlaines are named after Verlaine. Their most popular song "Death and the Maiden" references his shooting of Rimbaud.

- The time Verlaine and Rimbaud spent together was the subject of the 1995 film Total Eclipse, directed by Agnieszka Holland and with a screenplay by Christopher Hampton, based on his play. Verlaine was portrayed by David Thewlis and Leonardo DiCaprio played Rimbaud.

- The poem Crime of Love was set to music for the album Feasting with Panthers, released in 2011 by Marc Almond and Michael Cashmore. It was adapted and translated by Jeremy Reed.

- Bob Dylan's iconic "You're Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go," has the lyric, "Situations have ended sad; Relationships have all been bad; Mine've been like Verlaine's and Rimbaud".

- Singer Lydia Loveless has a song called 'Verlaine Shot Rimbaud' on her album Somewhere Else.

Works in French (original)

Verlaine's Complete Works are available in critical editions from the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

- Libretti for Vaucochard et Fils 1er and Fisch-Ton-Kan (1864)[20] (music by Chabrier)

- Poèmes saturniens (1866)

- Les Amies (1867)

- "Clair de Lune" (1869)

- Fêtes galantes (1869)

- La Bonne Chanson (1870)

- Romances sans paroles (1874)

- Sagesse (1880)

- Les Poètes maudits (1884)

- Jadis et naguère (Verlaine) (1884)

- Les Mémoires d'un veuf (1886)

- Amour (1888)

- À Louis II de Bavière (1888)

- Parallèlement (1889)

- Dédicaces (1890)

- Femmes (1890)

- Hombres (1891)

- Bonheur (1891)

- Mes hôpitaux (1891)

- Chansons pour elle (1891)

- Liturgies intimes (1892)

- Mes prisons (1893)

- Élégies (1893)

- Odes en son honneur (1893)

- Dans les limbes (1894)

- Épigrammes (1894)

- Confessions (1895)

Works in English (translation)

Although widely regarded as a major French poet -- to the effect that towards the end of his life he was sobriquetted as "Le Prince des Poètes" (The Prince of Poets) in the French-speaking world -- surprisingly very few of Verlaine's major works have been translated in their entirety (vs. selections therefrom) into English. Here's a list to help track those known to exist.

| French Title (Original) | English Title | Genre | Publisher, &c. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poèmes saturniens | Poems Under Saturn | Poetry | Princeton University Press, 2011. Translated by Karl Kirchwey. ISBN 978-0-69114-486-3 |

| Romances sans paroles | Songs Without Words | Poetry | Omnidawn, 2013. Translated by Donald Revell. ISBN 978-1-89065-087-2 |

| Mes Hôpitals | My Hospitals & My Prisons | Autobiography | Sunny Lou Publishing. Translated by Richard Robinson. ISBN 978-1-73547-760-2 |

| Mes Prisons | My Hospitals & My Prisons | Autobiography | Sunny Lou Publishing. Translated by Richard Robinson. ISBN 978-1-73547-760-2 |

References

- "Verlaine". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Shapiro, Norman R., One Hundred and One Poems by Paul Verlaine, University of Chicago Press, 1999

- "Paul Verlaine". Litweb.net. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- Willsher, Kim (17 October 2015). "How 555 nights in jail helped to make Paul Verlaine a 'prince of poets'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Hanson, Ellis. (1998). Decadence and Catholicism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19444-6. OCLC 502187924.

- Delahave, Ernst (2006). "Paul Verlaine" (PDF). Martin and Bev Gosling. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- Delahave, Ernst (22 May 2010). "Biography of Paul Verlaine". The Left Anchor. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "Lucien Létinois | French author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Orledge, Robert (1979). Gabriel Fauré. London: Eulenburg Books. p. 78. ISBN 0-903873-40-0.

- Rolf, Marie. Page 7 of liner notes to Forgotten Songs by Claude Debussy, with Dawn Upshaw and James Levine, Sony SK 67190.

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 48689-48690). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- Verlane, Paul (1882). "Art Poétique". Aesthetic Realism Online Library. Translated by Eli Siegel (1968). Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Lightbody, Bradley (4 June 2004). The Second World War: Ambitions to Nemesis. Routledge. p. 214. ISBN 0-415-22405-5. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

The French Resistance ... was given 24 hours' warning of the invasion by a BBC radio broadcast. A single line from the poem "Chanson d'automne" by Paul Verlaine, "blessent mon coeur D'une langueur monotone" (wound my heart with a monotonous languor) was the order for action.

- Bowden, Mark; Ambrose, Stephen E. (2002). Our finest day: D-Day: June 6, 1944. Chronicle. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8118-3050-8.

- Hall, Anthony (2004). D-Day: Operation Overlord Day by Day. Zenith. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7603-1607-8.

- Roberts, Andrew (2011). The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War. HarperCollins. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-06-122859-9.

- Olga Ivinskaya, A Captive of Time: My Years with Boris Pasternak, (1978). Page 34.

- http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks05/0501181.txt

- (in Russian) David Tukhmanov

- Delage R. Emmanuel Chabrier. Paris, Fayard, 1999, p692-3.

External links

- Works by Paul Verlaine at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Paul Verlaine at Internet Archive

- Works by Paul Verlaine at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Free scores of works by Paul Verlaine in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- (in French) Works by Paul Verlaine at Webnet

- (in French) Works by Paul Verlaine in PDF at Livres et Ebooks

- (in English) Resignation and Other Poems at New Translations (not operational 02/09/2019)

- Four poems by Verlaine, translated by Norman R. Shapiro, with original French texts

- Paul Verlaine at Find a Grave