Liverpool Cathedral

cathedral in the same city|Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral}}

| Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of Christ | |

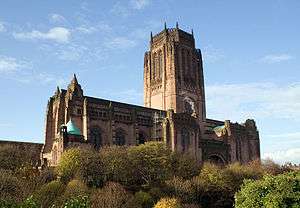

.jpg) Liverpool Anglican Cathedral, St James's Mount | |

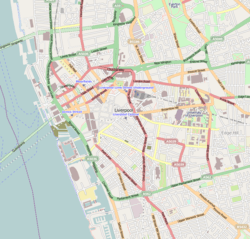

Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool Shown within Liverpool | |

| 53°23′51″N 2°58′23″W | |

| Location | Liverpool |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Tradition | Central churchmanship |

| Website | liverpoolcathedral.org.uk |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Giles Gilbert Scott |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Years built | 1904–1978 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 188.67 m (619.0 ft) |

| Nave height | 35.3 m (116 ft) |

| Choir height | 35.3 m (116 ft) |

| Number of towers | 1 |

| Tower height | 100.8 m (331 ft)1 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Liverpool (since 1880) |

| Province | York |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Paul Bayes |

| Dean | Sue Jones |

| Precentor | Myles Davies (Vice Dean) |

| Canon Chancellor | Ellen Loudon (Dir. Social Justice) |

| Canon(s) | 2 vacancies |

| Canon Missioner | Neal Barnes |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Lee Ward |

| Organist(s) | Ian Tracey; Daniel Bishop (Associate Organist) |

Liverpool Cathedral is the Cathedral of the Diocese of Liverpool, built on St James's Mount in Liverpool, and the seat of the Bishop of Liverpool. It may be referred to as the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool (as recorded in the Document of Consecration) or the Cathedral Church of the Risen Christ, Liverpool, being dedicated to Christ 'in especial remembrance of his most glorious Resurrection'.[1] Liverpool Cathedral is the largest cathedral and religious building in Britain,[2] and the eighth largest church in the world.

The cathedral is based on a design by Giles Gilbert Scott and was constructed between 1904 and 1978. The total external length of the building, including the Lady Chapel (dedicated to the Blessed Virgin), is 207 yards (189 m) making it the longest cathedral in the world;[n 1] its internal length is 160 yards (150 m). In terms of overall volume, Liverpool Cathedral ranks as the fifth-largest cathedral in the world[3] and contests with the incomplete Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City for the title of largest Anglican church building.[4] With a height of 331 feet (101 m) it is also one of the world's tallest non-spired church buildings and the third-tallest structure in the city of Liverpool. The cathedral is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building.[5]

The Anglican cathedral is one of two cathedrals in the city. The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Liverpool is situated approximately half a mile to the north. The cathedrals are linked by Hope Street, which takes its name from William Hope, a local merchant whose house stood on the site now occupied by the Philharmonic Hall, and was named long before either cathedral was built.

History

Background

J. C. Ryle was installed as the first Bishop of Liverpool in 1880, but the new diocese had no cathedral, merely a "pro-cathedral", the parish church of St Peter, Church Street. St Peter's was unsatisfactory; it was too small for major church events, and moreover was, in the words of the Rector of Liverpool, "ugly & hideous".[6] In 1885 an Act of Parliament authorised the building of a cathedral on the site of the existing St John's Church, adjacent to St George's Hall.[7] A competition was held for the design, and won by William Emerson. The site proved unsuitable for the erection of a building on the scale proposed, and the scheme was abandoned.[7]

In 1900 Francis Chavasse succeeded Ryle as Bishop, and immediately revived the project to build a cathedral.[8] There was some opposition from among members of Chavasse's diocesan clergy, who maintained that there was no need for an expensive new cathedral. The architectural historian John Thomas argues that this reflected "a measure of factional strife between Liverpool Anglicanism's very Evangelical or Low Church tradition, and other forces detectable within the religious complexion of the new diocese."[9] Chavasse, though himself an Evangelical, regarded the building of a great church as "a visible witness to God in the midst of a great city".[9] He pressed ahead, and appointed a committee under William Forwood to consider all possible sites. The St John's site being ruled out, Forwood's committee identified four locations: St Peter's and St Luke's, which were, like St John's, found to be too restricted; a triangular site at the junction of London Road and Monument Place;[n 2] and St James's Mount.[10] There was considerable debate about the competing merits of the two possible sites, and Forwood's committee was inclined to favour the London Road triangle. However, the cost of acquiring it was too great, and the St James's Mount site was recommended.[10] An historian of the cathedral, Vere Cotton, wrote in 1964:

Looking back after an interval of sixty years, it is difficult to realise that any other decision was even possible. With the exception of Durham, no English cathedral is so well placed to be seen to advantage both from a distance and from its immediate vicinity. That such a site, convenient to yet withdrawn from the centre of the city … dominating the city and clearly visible from the river, should have been available is not the least of the many strokes of good fortune which have marked the history of the cathedral.[10]

Fund-raising began, and new enabling legislation was passed by Parliament. The Liverpool Cathedral Act 1902 authorised the purchase of the site and the building of a cathedral, with the proviso that as soon as any part of it opened for public worship, St Peter's Church should be demolished and its site sold to provide the endowment of the new cathedral's chapter. St Peter's place as Parish Church of Liverpool would be taken by the existing church of St Nicholas near the Pier Head.[10] St Peter's Church closed in 1919, and was finally demolished in 1922.[11]

1901 competition

In late 1901, two well-known architects were appointed as assessors for an open competition for architects wishing to be considered for the design of the cathedral.[12] G. F. Bodley was a leading exponent of the Gothic revival style, and a former pupil and relative by marriage of George Gilbert Scott.[13] R. Norman Shaw was an eclectic architect, having begun in the Gothic style, and later favouring what his biographer Andrew Saint calls "full-blooded classical or imperial architecture".[14]

Architects were invited by public advertisement to submit portfolios of their work for consideration by Bodley and Shaw. From these, the two assessors selected a first shortlist of architects to be invited to prepare drawings for the new building. It was stipulated that the designs were to be in the Gothic style.[15] Robert Gladstone, a member of the committee to which the assessors were to report said, "There could be no question that Gothic architecture produced a more devotional effect upon the mind than any other which human skill had invented."[16] This condition caused controversy. Reginald Blomfield and others protested at the insistence on a Gothic style, a "worn-out flirtation in antiquarianism, now relegated to the limbo of art delusions."[17] An editorial in The Times observed, "To impose a preliminary restriction is unwise and impolitic … the committee must not hamper itself at starting with a condition which is certain to exclude many of the best men."[18] Eventually it was agreed that the assessors would also consider "designs of a Renaissance or Classical character".[19]

For architects, the competition was an important event; not only was it for one of the largest building projects of its time, but it was only the third opportunity to build an Anglican cathedral in England since the Reformation in the 16th century (St Paul's Cathedral being the first, rebuilt from scratch after the Great Fire of London in 1666, and Truro Cathedral being the second, begun in the 19th century).[19] The competition attracted 103 entries,[19] from architects including Temple Moore, Charles Rennie Mackintosh,[20] Charles Reilly,[21] and Austin and Paley.[22]

In 1903, the assessors recommended a proposal submitted by the 22-year-old Giles Gilbert Scott, who was still an articled pupil working in Temple Moore's practice,[23] and had no existing buildings to his credit. He told the assessors that so far his only major work had been to design a pipe-rack.[24] The choice of winner was even more contentious with the Cathedral Committee when it was discovered that Scott was a Roman Catholic,[n 3] but the decision stood.[23]

Scott's first design

Although young, Scott was steeped in ecclesiastical design and well versed in the Gothic revival style, his grandfather, George Gilbert Scott, and father George Gilbert Scott, Jr. having designed numerous churches.[25] George Bradbury, the surveyor to the Cathedral Committee, reported, "Mr. Scott seems to have inherited the architectural genius so marked in the Scott family for the last three or four generations ... He is very pleasant, agreeable, enthusiastic, tall and looks considerably older than he actually is."[9] Appearances notwithstanding, Scott's inexperience prompted the Cathedral Committee to appoint Bodley to oversee the detailed architectural design and building work. Work began without delay. The foundation stone was laid by Edward VII in 1904.[6]

Cotton observes that it was generous of Bodley to enter into a working relationship with a young and untried student.[26] Bodley had been a close friend of Scott's father, but his collaboration with the young Scott was fractious, especially after Bodley accepted commissions to design two cathedrals in the US,[n 4] necessitating frequent absences from Liverpool.[23] Scott complained that this "has made the working partnership agreement more of a farce than ever, and to tell the truth my patience with the existing state of affairs is about exhausted".[23] Scott was on the point of resigning when Bodley died suddenly in 1907, leaving him in charge.[27] The Cathedral Committee appointed Scott sole architect, and though it reserved the right to appoint another co-architect, it never seriously considered doing so.[9]

Scott's 1910 redesign

In 1909, free of Bodley and growing in confidence, Scott submitted an entirely new design for the main body of the cathedral.[28] His original design had two towers at the west end[n 5] and a single transept; the revised plan called for a single central tower 85.344 metres (280.00 ft) high, topped with a lantern and flanked by twin transepts.[30][n 6] The Cathedral Committee, shaken by such radical changes to the design they had approved, asked Scott to work his ideas out in fine detail and submit them for consideration.[28] He worked on the plans for more than a year, and in November 1910, the committee approved them.[28] In addition to the change in the exterior, Scott's new plans provided more interior space.[32] At the same time Scott modified the decorative style, losing much of the Gothic detailing and introducing a more modern, monumental style.[33]

The Lady Chapel (originally intended to be called the Morning Chapel),[9] the first part of the building to be completed, was consecrated in 1910 by Chavasse in the presence of two Archbishops and 24 other Bishops.[34] The date, 29 June — St Peter's Day — was chosen to honour the pro-cathedral, now due to be demolished.[35] The Manchester Guardian described the ceremony:

The Bishop of Liverpool knocked on the door with his pastoral staff, saying in a loud voice, "Open ye the gates." The doors having been flung open, the Earl of Derby, resplendent in the golden robes of the Chancellor of Liverpool University, presented Dr. Chavasse with the petition for consecration. … The Archbishop of York, whose cross was carried before him and who was followed by two train-bearers clad in scarlet cassocks, was conducted to the sedilla and the rest of the Bishops, with the exception of Dr. Chavasse, who knelt before his episcopal chair in the sanctuary, found accommodation in the choir stalls.[36]

The richness of the décor of the Lady Chapel may have dismayed some of Liverpool's Evangelical clergy. Thomas suggests that they were confronted with "a feminised building which lacked reference to the 'manly' and 'muscular Christian' thinking which had emerged in reaction to the earlier feminisation of religion."[9] He adds that the building would have seemed to many to be designed for Anglo-Catholic worship.[9]

Second phase

Work was severely limited during the First World War, with a shortage of manpower, materials and donations.[37] By 1920, the workforce had been brought back up to strength and the stone quarries at Woolton, source of the pinkish-red sandstone for most of the building, reopened.[37] The first section of the main body of the cathedral was complete by 1924. It comprised the chancel, an ambulatory, chapter house and vestries.[38] The section was closed with a temporary wall, and on 19 July 1924, the 20th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone, the cathedral was consecrated in the presence of George V and Queen Mary, and Bishops and Archbishops from around the globe.[37] Major works ceased for a year while Scott once again revised his plans for the next section of the building: the tower, the under-tower and the central transept.[39] The tower in his final design was higher and narrower than his 1910 conception.[40]

From July 1925 work continued steadily, and it was hoped to complete the whole section by 1940.[41] The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 caused similar problems to those of the earlier war. The workforce dwindled from 266 to 35; moreover, the building was damaged by German bombs during the May Blitz.[42] Despite these vicissitudes, the central section was complete enough by July 1941 to be handed over to the Dean and Chapter. Scott laid the last stone of the last pinnacle on the tower on 20 February 1942.[43] No further major works were undertaken during the rest of the war. Scott produced his plans for the nave in 1942, but work on it did not begin until 1948.[44] The bomb damage, particularly to the Lady Chapel, was not fully repaired until 1955.[45]

Completion

Scott died in 1960. The first bay of the nave was then nearly complete, and was handed over to the Dean and Chapter in April 1961. Scott was succeeded as architect by Frederick Thomas.[46] Thomas, who had worked with Scott for many years, drew up a new design for the west front of the cathedral. The Guardian commented, "It was an inflation beater, but totally in keeping with the spirit of the earlier work, and its crowning glory is the Benedicite Window designed by Carl Edwards and covering 1,600 sq. ft."[47]

The version recorded in Gavin Stamp's obituary of Richard Gilbert Scott, which appeared in The Guardian on 15 July 2017, differs slightly: "When his father died the following year (1960), Richard inherited the practice and was left to complete several jobs. He continued with the great work of building Liverpool Cathedral but, after adding two bays of the nave (using cheaper materials: concrete and fibreglass), he resigned when it was proposed drastically to alter his father's design. The cathedral was eventually completed with a much simplified and diminished west end drawn out by his father's former assistant, Roger Pinckney".[48]

The completion of the building was marked by a service of thanksgiving and dedication in October 1978, attended by Queen Elizabeth II. In the spirit of ecumenism that had been fostered in Liverpool, Derek Worlock, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Liverpool, played a major part in the ceremony.[49]

Dean and chapter

As of 22 January 2018:[50]

- Dean — Sue Jones (since 5 May 2018 institution)[51]

- Vice Dean & Canon Precentor — Myles Davies (canon since 2006; Precentor since 2008; Acting Dean, 2011–2012 & 2017–2018; also Vicar of Stanley until 2011)

- Canon Chancellor and Diocesan Director of Social Justice — Ellen Loudon (since 5 June 2016 installation)[52]

- a commissioners' canonry — vacant since 2 February 2019 (most recently "Canon for Discipleship")[53]

- a diocesan canonry — vacant since 12 November 2018 (most recently Canon for Mission and Evangelism and Diocesan Director of Pioneer Ministry)[54]

Completed building

The cathedral's official website gives the dimensions of the building as

- Length: 188.7 metres (619 ft)

- Area: 9,687.4 square metres (104,274 sq ft)

- Height of tower: 100.8 metres (331 ft)

- Choir vault: 35.3 metres (116 ft)

- Nave vault: 36.5 metres (120 ft)

- Under tower vault: 53.3 metres (175 ft)

- Tower arches: 32.6 metres (107 ft)

The cathedral was built mainly of local sandstone quarried from the South Liverpool suburb of Woolton. The last sections (The Well of the Cathedral at the west end in the 1960s and 1970s) used the closest matching sandstone that could be found from other NW quarries once the supply from Woolton had been exhausted.

The belltower is the largest, and also one of the tallest, in the world (see List of tallest churches in the world). It houses the world's highest (67 m (220 ft)) and heaviest (16.5 long tons (16.8 tonnes)) ringing peal of bells, and the third-heaviest bell (14.5 long tons (14.7 tonnes)) in the United Kingdom.[57]

Services and other uses

The cathedral is open daily all year round from 8:00 am to 6:00 pm (except Christmas Day when it closes to the public at 3 pm), and regular services are held every day of the week at 8:30 am: Morning Prayer (Holy Communion on Sundays). 12:05 pm Monday–Saturday (Communion) and Monday–Friday at 5:30pm (Evensong or said Evening Prayer according to day and time of year). At the weekend, there is also a 3pm Evensong service on Saturdays and Sundays with a main Cathedral Eucharist at 10:30 am, which attracts a large core congregation each week. It also has a more intimate Communion on Sundays at 4 pm. Since early 2011, the cathedral has also offered a regular, more informal form of cafe-style worship called "Zone 2", running parallel to its main Sunday Eucharist each week and held in the lower rooms in the Giles Gilbert Scott Function Suite (formerly the Western Rooms). The core services at 5:30pm on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, 10:30am on Sundays and 3pm Saturdays and Sundays are supported on each occasion during term time by the cathedral choir.[58]

Following the closure of their building in Rodney Street in 1975, the Liverpool St. Andrew's congregation of the Church of Scotland used the Radcliffe Room of the cathedral for Sunday services. The congregation finally disbanded in November 2016.[59]

Admission to the cathedral is free, but with a suggested donation of £5.[n 7] Car parking is available on site on a pay-on-exit basis. Parking is free for attendance at all services. Access to the main floor of the cathedral is restricted during services and some of the major events.[60]

The building also plays host to a wide range of events and special services including concerts, academic events involving local schools, graduations, exhibitions, family activities, seminars, conferences, corporate events, commemorative services, anniversary services and many more. Its maximum capacity for any major event including special services is 3,500 standing, or about 2,300 fully seated. The ground floor of the cathedral is fully accessible.

Liverpool Cathedral has its own specialist constabulary to keep watch on an all-year 24-hour basis. The Liverpool Cathedral Constables together with the York Minster Police and several other cathedrals' constable units are members of the Cathedral Constables' Association.[61]

Liverpool Cathedral also features on a page of the latest design of the British passport.[62]

Bells

.jpg)

At 67 m (220 ft) above floor level, the bells of Liverpool Cathedral are the highest and heaviest ringing peal in the world. [n 8] Two lifts are provided for the use of the bellringers and other visitors to the tower. The peal proper (hung for full-circle change ringing) consists of thirteen bells weighing a total of 16.5 long tons (16.8 tonnes), which are named the Bartlett Bells after Thomas Bartlett (died 4 September 1912), a native of Liverpool who bequeathed the funding.[63] The bells vary in size and note from the comparatively light 10 long cwt (510 kilograms) treble to the tenor weighing 4 long tons (4.1 tonnes). The 13th bell (sharp 2nd) is extra to the main 12-bell peal, and its purpose is to make possible ringing in a correct octave on lighter bells.[64] All thirteen bells were cast by Mears & Stainbank of Whitechapel in London.[65] The initial letters of the inscriptions on the thirteen bells spell out the name "Thomas Bartlett" (from tenor to treble).[66]

The Bartlett bells are hung in a circle around the bourdon bell "Great George".[n 9] At 14.5 long tons (14.7 tonnes), Great George is the third most massive bell in the British Isles. (Only the 16.5 long tons (16.8 tonnes) "Great Paul" of St Paul's Cathedral in London, and the 2012 Olympic Bell (22.91 tonnes) are heavier.) However, as the ringing mechanism of "Great Paul" is currently broken[67] (and has been for several years), and the Olympic bell is never rung,[68] Great George is currently the largest ringing bell in the British Isles. Great George, cast by Taylors of Loughborough and named in memory of George V, is hung in a pendant position and is sounded by means of a counterbalanced clapper.[69]

Music

- Organ

The organ, built by Henry Willis & Sons, is the largest pipe organ in the UK, and one of the largest musical instruments in the world. It has two five-manual consoles (one sited high up in one of the organ cases and the other, a mobile console, on the floor of the cathedral), 10,268 pipes and a trompette militaire.[70] There is an annual anniversary recital on the Saturday nearest to 18 October, the date of the organ's consecration. There is a two-manual Willis organ in the Lady Chapel.[71][72]

- Organists and Directors of Music

- 1880–1916 — Frederick Hampton Burstall (died 1916)

- 1915–1955 — Walter Henry Goss-Custard (Cathedral Organist)

- 1931–1982 — Ronald Woan (Director of Music)

- 1955–1980 — Noel Rawsthorne (Cathedral Organist)

- 1980–present — Ian Tracey (Organist and Master of the Choristers - 1982–2008. Organist Titulaire - 2008-)

- 2008–2017 — David Poulter (Director of Music)

- 2017–present — Lee Ward (Director of Music)

- Assistant organists

- Noel Rawsthorne 1949–1955 (afterwards organist)

- Lewis Rust (part-time) student at Liverpool Institute and ex-chorister

- Ian Tracey 1976–1980 (afterwards organist)

- Ian Wells 1980–2007

- Daniel Bishop 2010–present

- Organ scholars

- Lewis Rust (approx dates 1960–70)

- Ian Tracey (organist) (later organiste titulaire)

- Ian Wells (later, Holy Trinity, Southport)

- Geoff Williams 1983-85 (now Director of Music, St Anne's Stanley)

- Stephen Disley (now assistant organist and director of the girls' choir, Southwark Cathedral)

- Paul Daggett

- Martin Payne 1994–95

- David Leahey 1995–97

- Keith Hearnshaw 1997–98

- Michael Wynne

- Gerrard Callacher

- Daniel Bishop (later associate organist)

- Shean Bowers 2004–06 (later assistant director of music at Bath Abbey)

- Samuel Austin 2007–08 (later assistant director of music at Aldenham School)

- Martyn Noble (2009–11)

- James Speakman (2011–12)

- Daniel Mansfield (2014–2019)

- William Jeys (2019-)

Artists and sculptors

In 1931, Scott asked Edward Carter Preston to produce a series of sculptures for Liverpool Cathedral. The project was an immense undertaking which occupied the artist for the next thirty years. The work for the cathedral included fifty sculptures, ten memorials and several reliefs. Many inscriptions in the cathedral were jointly written by Dean Dwelly and the sculptor who subsequently carved them.

In 1993 "The Welcoming Christ", a large bronze sculpture by Dame Elisabeth Frink, was installed over the outside of the west door of the cathedral.[73] This was one of her last completed works, installed within days of her death.[74]

In 2003 the Liverpool artist, Don McKinlay, who knew Carter Preston from his youth, was commissioned by the cathedral to model an infant Christ to accompany the 15th century Madonna by Giovanni della Robbia Madonna now situated in the Lady Chapel.[75]

In 2008 a work entitled "For You" by Tracey Emin was installed at the west end of cathedral the below the Benedicite window. The pink neon sign reads "I felt you and I knew you loved me", and was installed when Liverpool became European Capital of Culture. The work was originally intended to be a temporary installation for one month as part of the Capital of Culture programme, but is now a permanent feature.[73]

Another work by Emin, "The Roman Standard" takes the form of a small bronze sparrow on a metal pole, and was installed in 2005 outside the Oratory Chapel close to the west end of the cathedral.[76] The sparrow was stolen (twice) in 2008, but on both occasions was returned and replaced.[77]

Stained glass

The firm of James Powell and Sons (Whitefriars), Ltd., of London, provided most of the stained glass designs. John William Brown (1842–1928) designed the Te Deum window in the east end of the cathedral, as well as the original windows for the Lady Chapel, which was heavily damaged during German bombing raids in 1940. The glass in the Lady Chapel was replaced with designs, based on the originals, by James Humphries Hogan (1883–1948). He was one of the most prolific of the Powell and Sons designers; his designs can also be seen in the large north and south windows in the central space of the cathedral (each 100 feet tall). Later artists include William Wilson (1905–1972), who began his work at Liverpool Cathedral after the death of Hogan, Herbert Hendrie (1887–1946), and Carl Edwards (1914–1985), who designed the Benedicite window in the west front. The cathedral has approximately 1,700 m² of stained glass.[78]

Burials

Chavasse and Scott are buried in the precinct of the cathedral, the former in Founder's Plot, and the latter at the west end of the site.[79] Clergy buried within the cathedral include the bishops Albert David and David Sheppard. Among the benefactors whose remains are buried in the cathedral are William and Edmund Vestey and Frederick Radcliffe. The ashes of the donor of the cathedral bells, Thomas Bartlett are interred in a casket in the ringing room.[79] At the rear of the memorial to the 55th (West Lancashire) Infantry Division rest the ashes of Hugh Jeudwine, who commanded the division from its formation in 1916 until the end of the First World War.[80]

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- The only church building to exceed it in length is St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, which however is not a cathedral.

- Monument Place was later renamed Pembroke Place.[10]

- At this time it was customary for architects to undertake ecclesiastical work only for the denomination to which they belonged. When Bodley's partner Thomas Garner became a Roman Catholic in 1897, the partnership was dissolved and Garner's church work was thereafter exclusively for the Roman Catholic church while Bodley worked solely on Anglican churches.[9]

- These were for Washington, D.C. (for American Episcopal church) and San Francisco. The latter was not built.[13]

- Because of the shape of the St James's Mount site, the cathedral is oriented nearly north to south rather than, as is traditional, west to east. Cotton and other writers use the points of the compass in their liturgical sense: thus the high altar is at the "east end", and the main entrance at the "west end."[29]

- In an article in 1977 Paul Barker suggests that Scott altered his design "to come closer to Mackintosh's plans".[31]

- There is a charge for those who wish take the visitor's Great Space experience, including a short film showing the construction of the cathedral, an audio tour (several different languages and a junior version available) and an opportunity to go up the tower (fee payable). The tower is closed to the visiting public during times of particularly bad or windy weather or if a special event or service prevents access.

- At 116 short tons (105 t), the Bell of Good Luck is the largest hanging bell in the world, but it does not move; it is sounded by an external clapper. At 216 tons, the Tsar Bell is even more massive. This bell, on display on a stone pedestal on the grounds of the Moscow Kremlin, is broken. Hence, it neither hangs nor rings.

- The names of the other bells are Emmanuel (tenor), James (11th), Oswald (10th), Peter (9th), Martin (8th), Nicholas (7th), Michael (6th), Guthlac (5th), Gilbert (4th), Chad (3rd), Paul (2nd), David (2nd sharp) and Bede (treble).[66]

- References

- The Form and Order of the Consecration of the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool, 19 July 1924

- Liverpool Cathedral Archived 9 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 October 2017

- "The Cathedrals of Britain". Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- The title depends on which dimensions are counted. For a discussion on the matter of size, see Quirk, Howard E., The Living Cathedral: St. John the Divine: A History and Guide (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Co., 1993), p. 15-16.

- Historic England, "Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ (1361681)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 19 August 2012

- "History" Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 2 October 2011

- Cotton 1964, p. 1

- Bailey & Millington 1957, p. 48

- Thomas, John. "The 'Beginnings of a Noble Pile': Liverpool Cathedral's Lady Chapel (1904–10)",Architectural History, Vol. 48 (2005), pp. 257–290 (subscription required) Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Cotton 1964, p. 2

- "St Peter's Church, Church St, Liverpool". Lancashire OnLine Parish Clerks. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Cotton 1964, p. 3

- Hall, Michael. "Bodley, George Frederick (1827–1907)", Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- Saint, Andrew. "Shaw, Richard Norman (1831–1912)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- Shallcross, T Myddelton. "The Proposed New Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 8 October 1901, p. 13

- "Ecclesiastical Intelligence", The Times, 8 October 1901, p. 8

- "Concordia", "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 19 October 1901, p. 11

- "The Liverpool Cathedral Controversy", The Times, 23 October 1901, p. 7

- "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 25 September 1902, p. 8

- "Design for Liverpool Anglican Cathedral competition: south elevation 1903" Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, accessed 2 October 2011

- Powers 1996, p. 2

- Brandwood et al. 2012, pp. 162–164

- Stamp. Gavin. "Scott, Sir Giles Gilbert (1880–1960)", Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- "Liverpool's 75-year-old infant", The Guardian, 21 October 1978, p. 9

- Cotton 1964, p. 25

- Cotton 1964, p. 24

- Cotton 1964, p. 22

- Cotton 1964, p. 28

- Cotton 1964, xvi

- Cotton 1964, p. 31

- Barker, Paul. "The might have been – Charles Rennie, Mackintosh and the Modern Movement", The Times, 14 July 1977, p. 8

- Cotton 1964, pp. 28, 30 and 32

- Cotton 1964, pp. 29–30

- Forwood, William. "Liverpool Cathedral — Consecration of the Lady Chapel", The Times, 30 June 1910, p. 9

- "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 30 June 1910, p. 11

- "Liverpool Cathedral — Consecration of the Lady Chapel", The Manchester Guardian, 30 June 1910, p. 7

- Cotton 1964, p. 6

- "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 19 June 1924, p. 13

- Cotton 1964, p. 7

- Cotton 1964, p. 32

- Cotton 1964, p. 8

- Cotton 1964, pp. 9–10

- Cotton 1964, p. 10

- Cotton 1964, pp. 10–11

- Cotton 1964, p. 11

- McNay, Thomas. "Liverpool's Anglican Cathedral", The Guardian, 24 October 1978, p. 8

- Riley, Joe. "Finished — but for the way in to the nave", The Guardian, 25 October 1978, p. 8

- Gavin Stamp. "Richard Gilbert Scott obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Chartres, John. "New Liverpool Anglican cathedral dedicated", The Times, 26 October 1978, p. 2

- Liverpool Cathedral — Cathedral People Archived 23 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 22 January 2018)

- "Invitation to the Installation of 8th Dean of Liverpool". Diocese of Liverpool. 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Diocese of Liverpool — Clergy Moves, 11 April 2016 Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 22 January 2018)

- "Liverpool Cathedral - Canon Richard White to be Director of Making and Nurturing Disciples at Diocese of York". Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Art in the Cathedral". Liverpool Cathedral. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- Catherine Jones (26 September 2008). "Message of love to Liverpool from Tracey Emin". Liverpool Echo.

- "Cathedral" Archived 18 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 3 October 2011

- "Service Times" Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 3 October 2011

- “Word of Life” Archived 6 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 28 March 2018

- "Opening Hours" Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 3 October 2011

- The Cathedral Constables' Association Archived 8 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 22 June 2012

- Liverpool Echo Archived 8 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 October 2017

- Cotton 1964, p. 151

- Bryant, David. "The History and Use of Semitone Bells". Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- Cotton 1964, p. 153

- Cotton 1964, pp. 153–157

- "The Organs & Bells - St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Ringing off: 23 tonne London Olympic bell falls silent". The Times. 1 April 2016. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Cotton 1964, p. 152

- "The Organ in the Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool". Liverpool Organs. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- Cotton 1964, pp. 159–164

- "The Lady Chapel Organ in the Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool". Liverpool Organs. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013.

- "Art in the Cathedral". Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Pepin, David (2004). Discovering Cathedrals. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 9780747805977. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Hidden gems", Daily Post, Liverpool, 6 November 2010

- "Emin unveils sparrow sculpture". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- "Stolen Emin sparrow returns again". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Purvis, Sean (18 January 2015). "Liverpool Cathedral: 11 things you never knew about historic landmark". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Cotton 1964, p. 148

- "War Memorial Archive". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Sources

- Bailey, F A; Millington, R (1957). The Story of Liverpool. Liverpool: Corporation of the City of Liverpool. OCLC 19865965.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brandwood, Geoff; Austin, Tim; Hughes, John; Price, James (2012). The Architecture of Sharpe, Paley and Austin. Swindon: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-84802-049-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotton, Vere E (1964). The Book of Liverpool Cathedral. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. OCLC 2286856.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Powers, Alan (1996). "Liverpool and Architectural Education in the Early Twentieth Century". In Sharples, Joseph (ed.). Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture 1904–1933. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 0-85323-901-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Further reading

- Cotton, Vere E (1964). The Liverpool Cathedral Official Handbook. Liverpool: Littlebury Bros for Liverpool Cathedral Committee. OCLC 44551681.

- Vincent, Noel (2002). The Stained Glass of Liverpool Cathedral. Norwich: Jarrold. ISBN 0-7117-2589-6.

- Thomas, John (2018). Liverpool Cathedral. Themes and Forms in a Great Modern Church Building. Wolverhampton: Twin Books. ISBN 978-0-9934781-3-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liverpool Anglican Cathedral. |

- Liverpool Pictorial Images of Liverpool Anglican cathedral

- Official website

- Catherdral Blog website containing daily Cathedral blog, and all sermons, talks, lectures and courses given in the Cathedral in text and mp3 file format

- The Liverpool Shakespeare Festival Annual theatrical performance inside the Cathedral

- Virtual Tours of Liverpool Cathedral Virtual Tours of Liverpool Cathedral

- New Bridge design

- Description and pictures of the cathedral organ.

- Details of the main organ from the National Pipe Organ Register

- Details of the organ in the Lady Chapel from the National Pipe Organ Register

- Details of the Cathedral bells from Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers

- Interview with Canon Justin Welby, dean of Liverpool Cathedral

- St. Andrew's Church of Scotland Liverpool website