Polychlorinated biphenyl

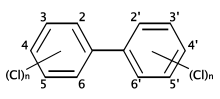

A polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) is an organic chlorine compound with the formula C12H10−xClx. Polychlorinated biphenyls were once widely deployed as dielectric and coolant fluids in electrical apparatus, carbonless copy paper and in heat transfer fluids.[2]

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| UN number | UN 2315 |

| Properties | |

| C12H10−xClx | |

| Molar mass | Variable |

| Appearance | Light yellow or colorless, thick, oily liquids[1] |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Because of their longevity, PCBs are still widely in use, even though their manufacture has declined drastically since the 1960s, when a host of problems were identified.[3] With the discovery of PCBs' environmental toxicity, and classification as persistent organic pollutants, their production was banned by United States federal law in 1978, and by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2001.[4] The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), rendered PCBs as definite carcinogens in humans. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), PCBs cause cancer in animals and are probable human carcinogens.[5] Many rivers and buildings, including schools, parks, and other sites, are contaminated with PCBs and there has been contamination of food supplies with the substances.

Some PCBs share a structural similarity and toxic mode of action with dioxins.[6] Other toxic effects such as endocrine disruption (notably blocking of thyroid system functioning) and neurotoxicity are known.[7]

The bromine analogues of PCBs are polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs), which have analogous applications and environmental concerns.

An estimated 1.2 million tons have been produced globally.[8] Though the federal ban also became enforced by the EPA in 1979, PCBs still found ways to create health problems in later years through a continued presence in soil and sediment and some products which were made before 1979 as well.[9] In 1988, Tanabe estimated 370,000 tons were in the environment globally and 780,000 tons were present in products, landfills and dumps or kept in storage.[8]

Physical and chemical properties

Physical properties

The compounds are pale-yellow viscous liquids. They are hydrophobic, with low water solubilities: 0.0027–0.42 ng/L for Aroclors,[10] but they have high solubilities in most organic solvents, oils, and fats. They have low vapor pressures at room temperature. They have dielectric constants of 2.5–2.7,[11] very high thermal conductivity,[10] and high flash points (from 170 to 380 °C).[10]

The density varies from 1.182 to 1.566 g/cm3.[10] Other physical and chemical properties vary widely across the class. As the degree of chlorination increases, melting point and lipophilicity increase, and vapour pressure and water solubility decrease.[10]

PCBs do not easily break down or degrade, which made them attractive for industries. PCB mixtures are resistant to acids, bases, oxidation, hydrolysis, and temperature change.[12] They can generate extremely toxic dibenzodioxins and dibenzofurans through partial oxidation. Intentional degradation as a treatment of unwanted PCBs generally requires high heat or catalysis (see Methods of destruction below).

PCBs readily penetrate skin, PVC (polyvinyl chloride), and latex (natural rubber).[13] PCB-resistant materials include Viton, polyethylene, polyvinyl acetate (PVA), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), butyl rubber, nitrile rubber, and Neoprene.[13]

Structure and toxicity

PCBs are derived from biphenyl, which has the formula C12H10, sometimes written (C6H5)2. In PCBs, some of the hydrogen atoms in biphenyl are replaced by chlorine atoms. There are 209 different chemical compounds in which one to ten chlorine atoms can replace hydrogen atoms. PCBs are typically used as mixtures of compounds and are given the single identifying CAS number 1336-36-3 . About 130 different individual PCBs are found in commercial PCB products.[10]:2

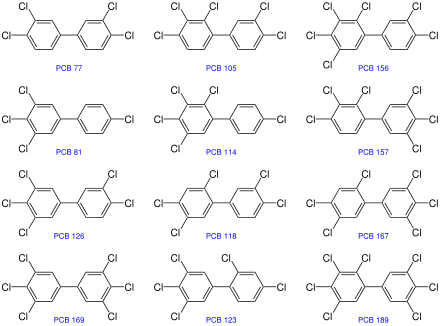

Toxic effects vary depending on the specific PCB. In terms of their structure and toxicity, PCBs fall into two distinct categories, referred to as coplanar or non-ortho-substituted arene substitution patterns and noncoplanar or ortho-substituted congeners.

- Coplanar or non-ortho

- The coplanar group members have a fairly rigid structure, with their two phenyl rings in the same plane. It renders their structure similar to polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans, and allows them to act like PCDDs, as an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in organisms. They are considered as contributors to overall dioxin toxicity, and the term dioxins and dioxin-like compounds is often used interchangeably when the environmental and toxic impact of these compounds is considered.[14][15]

- Noncoplanar

- Noncoplanar PCBs, with chlorine atoms at the ortho positions can cause neurotoxic and immunotoxic effects, but only at concentrations much higher than those normally associated with dioxins. They do not activate the AhR, and are not considered part of the dioxin group. Because of their lower toxicity, they are of less concern to regulatory bodies.[16][17]

Di-ortho-substituted, non-coplanar PCBs interfere with intracellular signal transduction dependent on calcium which may lead to neurotoxicity.[18] ortho-PCBs can disrupt thyroid hormone transport by binding to transthyretin.[19]

Alternative names

Commercial PCB mixtures were marketed under the following names:[20][21]

|

Brazil

Czech Republic and Slovakia

France

Germany

Italy

|

Japan

Former USSR

United Kingdom

|

United States

|

Aroclor mixtures

The only North American producer, Monsanto Company, marketed PCBs under the trade name Aroclor from 1930 to 1977. These were sold under trade names followed by a four-digit number. In general, the first two digits refer to the product series as designated by Monsanto (e.g. 1200 or 1100 series); the second two numbers indicate the percentage of chlorine by mass in the mixture. Thus, Aroclor 1260 is a 1200 series product and contains 60% chlorine by mass. It is a myth that the first two digits referred to the number of carbon atoms; the number of carbon atoms do not change in PCBs. The 1100 series was a crude PCB material which was distilled to create the 1200 series PCB product.[23]

The exception to the naming system is Aroclor 1016 which was produced by distilling 1242 to remove the highly chlorinated congeners to make a more biodegradable product. "1016" was given to this product during Monsanto's research stage for tracking purposes but the name stuck after it was commercialized.

Different Aroclors were used at different times and for different applications. In electrical equipment manufacturing in the US, Aroclor 1260 and Aroclor 1254 were the main mixtures used before 1950; Aroclor 1242 was the main mixture used in the 1950s and 1960s until it was phased out in 1971 and replaced by Aroclor 1016.[10]

Production

One estimate (2006) suggested that 1 million tonnes of PCBs had been produced. 40% of this material was thought to remain in use.[2] Another estimate put the total global production of PCBs on the order of 1.5 million tonnes. The United States was the single largest producer with over 600,000 tonnes produced between 1930 and 1977. The European region follows with nearly 450,000 tonnes through 1984. It is unlikely that a full inventory of global PCB production will ever be accurately tallied, as there were factories in Poland, East Germany, and Austria that produced unknown amounts of PCBs. In East region of Slovakia there is still 21 500 tons of PCBs stored.[24]

Applications

The utility of PCBs is based largely on their chemical stability, including low flammability and high dielectric constant. In an electric arc, PCBs generate incombustible gases.

Use of PCBs is commonly divided into closed and open applications.[2] Examples of closed applications include coolants and insulating fluids (transformer oil) for transformers and capacitors, such as those used in old fluorescent light ballasts,[25] hydraulic fluids, lubricating and cutting oils, and the like. In contrast, the major open application of PCBs was in carbonless copy ("NCR") paper, which even presently results in paper contamination.[26]

Other open applications were as plasticizers in paints and cements, stabilizing additives in flexible PVC coatings of electrical cables and electronic components, pesticide extenders, reactive flame retardants and sealants for caulking, adhesives, wood floor finishes, such as Fabulon and other products of Halowax in the U.S.,[27] de-dusting agents, waterproofing compounds, casting agents.[10] It was also used as a plasticizer in paints and especially "coal tars" that were used widely to coat water tanks, bridges and other infrastructure pieces.

Modern sources include pigments, which may be used in inks for paper or plastic products.[28]

Environmental transport and transformations

PCBs have entered the environment through both use and disposal. The environmental fate of PCBs is complex and global in scale.[10]

Water

Because of their low vapour pressure, PCBs accumulate primarily in the hydrosphere, despite their hydrophobicity, in the organic fraction of soil, and in organisms. The hydrosphere is the main reservoir. The immense volume of water in the oceans is still capable of dissolving a significant quantity of PCBs.

As the pressure of ocean water increases with depth, PCBs become heavier than water and sink to the deepest ocean trenches where they are concentrated.[29]

Air

A small volume of PCBs has been detected throughout the earth's atmosphere. The atmosphere serves as the primary route for global transport of PCBs, particularly for those congeners with one to four chlorine atoms.

In the atmosphere, PCBs may be degraded by hydroxyl radicals, or directly by photolysis of carbon–chlorine bonds (even if this is a less important process).

Atmospheric concentrations of PCBs tend to be lowest in rural areas, where they are typically in the picogram per cubic meter range, higher in suburban and urban areas, and highest in city centres, where they can reach 1 ng/m3 or more. In Milwaukee, an atmospheric concentration of 1.9 ng/m3 has been measured, and this source alone was estimated to account for 120 kg/year of PCBs entering Lake Michigan.[30] In 2008, concentrations as high as 35 ng/m3, 10 times higher than the EPA guideline limit of 3.4 ng/m3, have been documented inside some houses in the U.S.[27]

Volatilization of PCBs in soil was thought to be the primary source of PCBs in the atmosphere, but research suggests ventilation of PCB-contaminated indoor air from buildings is the primary source of PCB contamination in the atmosphere.[31]

Biosphere

In the biosphere, PCBs can be degraded by the sun, bacteria or eukaryotes, but the speed of the reaction depends on both the number and the disposition of chlorine atoms in the molecule: less substituted, meta- or para-substituted PCBs undergo biodegradation faster than more substituted congeners.

In bacteria, PCBs may be dechlorinated through reductive dechlorination, or oxidized by dioxygenase enzyme. In eukaryotes, PCBs may be oxidized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme.

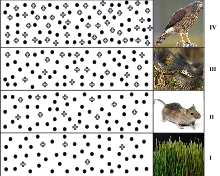

Like many lipophilic toxins, PCBs undergo biomagnification and bioaccumulation primarily due to the fact that they are easily retained within organisms.[32][33] Plastic pollution, specifically microplastics, are a major contributor of PCBs into the biosphere and especially into marine environments. PCBs concentrate in marine environments because freshwater systems, like rivers, act as a bridge for plastic pollution to be transported from terrestrial environments into marine environments.[34] It has been estimated that 88-95% of marine plastic is exported into the ocean by just 10 major rivers.[32] An organism can accumulate PCBs by consuming other organisms that have previously ingested PCBs from terrestrial, freshwater, or marine environments. The concentration of PCBs within an organism will increase over their lifetime; this process is called bioaccumulation. PCB concentrations within an organism also change depending upon which trophic level they occupy. When an organism occupies a high trophic level, like orcas or humans, they will accumulate more PCBs than an organism that occupies a low trophic level, like phytoplankton. If enough organisms with a trophic level are killed due to the accumulation of toxins, like PCB, a trophic cascade can occur. PCBs can cause harm to human health or even death when eaten.[35] PCBs can be transported by birds from aquatic sources onto land via feces and carcasses.[36]

Biochemical metabolism

Overview

PCBs undergo xenobiotic biotransformation, a mechanism used to make lipophilic toxins more polar and more easily excreted from the body.[37] The biotransformation is dependent on the number of chlorine atoms present, along with their position on the rings. Phase I reactions occur by adding an oxygen to either of the benzene rings by Cytochrome P450.[38] The type of P450 present also determines where the oxygen will be added; phenobarbital (PB)-induced P450s catalyze oxygenation to the meta-para positions of PCBs while 3-methylcholanthrene (3MC)-induced P450s add oxygens to the ortho–meta positions.[39] PCBs containing ortho–meta and meta–para protons can be metabolized by either enzyme, making them the most likely to leave the organism. However, some metabolites of PCBs containing ortho–meta protons have increased steric hindrance from the oxygen, causing increased stability and an increased chance of accumulation.[40]

Species dependent

Metabolism is also dependent on the species of organism; different organisms have slightly different P450 enzymes that metabolize certain PCBs better than others. Looking at the PCB metabolism in the liver of four sea turtle species (green, olive ridley, loggerhead and hawksbill), green and hawksbill sea turtles have noticeably higher hydroxylation rates of PCB 52 than olive ridley or loggerhead sea turtles. This is because the green and hawksbill sea turtles have higher P450 2-like protein expression. This protein adds three hydroxyl groups to PCB 52, making it more polar and water-soluble. P450 3-like protein expression that is thought to be linked to PCB 77 metabolism, something that was not measured in this study.[37]

Temperature dependent

Temperature plays a key role in the ecology, physiology and metabolism of aquatic species. The rate of PCB metabolism was temperature dependent in yellow perch (Perca flavescens). In fall and winter, only 11 out of 72 introduced PCB congeners were excreted and had halflives of more than 1,000 days. During spring and summer when the average daily water temperature was above 20 °C, persistent PCBs had halflives of 67 days. The main excretion processes were fecal egestion, growth dilution and loss across respiratory surfaces. The excretion rate of PCBs matched with the perch's natural bioenergetics, where most of their consumption, respiration and growth rates occur during the late spring and summer. Since the perch is performing more functions in the warmer months, it naturally has a faster metabolism and has less PCB accumulation. However, multiple cold-water periods mixed with toxic PCBs with coplanar chlorine molecules can be detrimental to perch health.[41]

Sex dependent

Enantiomers of chiral compounds have similar chemical and physical properties, but can be metabolized by the body differently. This was looked at in bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) for two main reasons: they are large animals with slow metabolisms (meaning PCBs will accumulate in fatty tissue) and few studies have measured chiral PCBs in cetaceans. They found that the average PCB concentrations in the blubber were approximately four times higher than the liver; however, this result is most likely age- and sex-dependent. As reproductively active females transferred PCBs and other poisonous substances to the fetus, the PCB concentrations in the blubber were significantly lower than males of the same body length (less than 13 meters).[42]

Health effects

The toxicity of PCBs varies considerably among congeners. The coplanar PCBs, known as nonortho PCBs because they are not substituted at the ring positions ortho to (next to) the other ring, (such as PCBs 77, 126 and 169), tend to have dioxin-like properties, and generally are among the most toxic congeners. Because PCBs are almost invariably found in complex mixtures, the concept of toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) has been developed to facilitate risk assessment and regulation, where more toxic PCB congeners are assigned higher TEF values on a scale from 0 to 1. One of the most toxic compounds known, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo[p]dioxin, a PCDD, is assigned a TEF of 1.[43] In June 2020, State Impact of Pennsylvania stated that "In 1979, the EPA banned the use of PCBs, but they still exist in some products produced before 1979. They persist in the environment because they bind to sediments and soils. High exposure to PCBs can cause birth defects, developmental delays, and liver changes."[9]

Exposure and excretion

In general, people are exposed to PCBs overwhelmingly through food, much less so by breathing contaminated air, and least by skin contact. Once exposed, some PCBs may change to other chemicals inside the body. These chemicals or unchanged PCBs can be excreted in feces or may remain in a person's body for years, with half lives estimated at 10–15 years.[44] PCBs collect in body fat and milk fat.[45] PCBs biomagnify up the food web and are present in fish and waterfowl of contaminated aquifers.[46] Human infants are exposed to PCBs through breast milk or by intrauterine exposure through transplacental transfer of PCBs[45] and are at the top of the food chain.[47]:249ff

Signs and symptoms

Humans

The most commonly observed health effects in people exposed to extremely high levels of PCBs are skin conditions, such as chloracne and rashes, but these were known to be symptoms of acute systemic poisoning dating back to 1922. Studies in workers exposed to PCBs have shown changes in blood and urine that may indicate liver damage. In Japan in 1968, 280 kg of PCB-contaminated rice bran oil was used as chicken feed, resulting in a mass poisoning, known as Yushō disease, in over 1800 people.[48] Common symptoms included dermal and ocular lesions, irregular menstrual cycles and lowered immune responses.[48][49][50] Other symptoms included fatigue, headaches, coughs, and unusual skin sores.[51] Additionally, in children, there were reports of poor cognitive development.[48] Women exposed to PCBs before or during pregnancy can give birth to children with lowered cognitive ability, immune compromise, and motor control problems.[52][45][53]

There is evidence that crash dieters that have been exposed to PCBs have an elevated risk of health complications. Stored PCBs in the adipose tissue become mobilized into the blood when individuals begin to crash diet.[54]

PCBs have shown toxic and mutagenic effects by interfering with hormones in the body. PCBs, depending on the specific congener, have been shown to both inhibit and imitate estradiol, the main sex hormone in females. Imitation of the estrogen compound can feed estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells, and possibly cause other cancers, such as uterine or cervical. Inhibition of estradiol can lead to serious developmental problems for both males and females, including sexual, skeletal, and mental development issues.[55] In a cross-sectional study, PCBs were found to be negatively associated with testosterone levels in adolescent boys.[56]

High PCB levels in adults have been shown to result in reduced levels of the thyroid hormone triiodothyronine, which affects almost every physiological process in the body, including growth and development, metabolism, body temperature, and heart rate. It also resulted in reduced immunity and increased thyroid disorders.[44][57]

Animals

Animals that eat PCB-contaminated food even for short periods of time suffer liver damage and may die. In 1968 in Japan, 400,000 birds died after eating poultry feed that was contaminated with PCBs.[58] Animals that ingest smaller amounts of PCBs in food over several weeks or months develop various health effects, including anemia; acne-like skin conditions (chloracne); liver, stomach, and thyroid gland injuries (including hepatocarcinoma), and thymocyte apoptosis.[44] Other effects of PCBs in animals include changes in the immune system, behavioral alterations, and impaired reproduction.[44] PCBs that have dioxin-like activity are known to cause a variety of teratogenic effects in animals. Exposure to PCBs causes hearing loss and symptoms similar to hypothyroidism in rats.[59]

Cancer

In 2013, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified dioxin-like PCBs as human carcinogens.[60] According to the U.S. EPA, PCBs have been shown to cause cancer in animals and evidence supports a cancer-causing effect in humans.[5] Per the EPA, studies have found increases in malignant melanoma and rare liver cancers in PCB workers.[5]

In 2013, the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) determined that the evidence for PCBs causing non-Hodgkin lymphoma is "limited" and "not consistent".[60] In contrast an association between elevated blood levels of PCBs and non-Hodgkin lymphoma had been previously accepted.[61] PCBs may play a role in the development of cancers of the immune system because some tests of laboratory animals subjected to very high doses of PCBs have shown effects on the animals' immune system, and some studies of human populations have reported an association between environmental levels of PCBs and immune response.[5]

Lawsuits related to health effects

In the early 1990s, Monsanto faced several lawsuits over harm caused by PCBs from workers at companies such as Westinghouse that bought PCBs from Monsanto and used them to build electrical equipment.[62] Monsanto and its customers, such as Westinghouse and GE, also faced litigation from third parties, such as workers at scrap yards that bought used electrical equipment and broke them down to reclaim valuable metals.[63][64] Monsanto settled some of these cases and won the others, on the grounds that it had clearly told its customers that PCBs were dangerous chemicals and that protective procedures needed to be implemented.

In 2003, Monsanto and Solutia Inc., a Monsanto corporate spin-off, reached a $700 million settlement with the residents of West Anniston, Alabama who had been affected by the manufacturing and dumping of PCBs.[65][66] In a trial lasting six weeks, the jury found that "Monsanto had engaged in outrageous behavior, and held the corporations and its corporate successors liable on all six counts it considered – including negligence, nuisance, wantonness and suppression of the truth."[67]

In 2014, the Los Angeles Superior Court found that Monsanto was not liable for cancers claimed to be from PCBs permeating the food supply of three plaintiffs who had developed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. After a four-week trial, the jury found that Monsanto’s production and sale of PCBs between 1935 and 1977 were not substantial causes of the cancer.[68]

In 2015, the cities of Spokane, San Diego, and San Jose initiated lawsuits against Monsanto to recover cleanup costs for PCB contaminated sites, alleging that Monsanto continued to sell PCBs without adequate warnings after they knew of their toxicity. Monsanto issued a media statement concerning the San Diego case, claiming that improper use or disposal by third-parties, of a lawfully sold product, was not the company's responsibility.[69][70][71][72]

In July 2015, a St Louis county court in Missouri found that Monsanto, Solutia, Pharmacia and Pfizer were not liable for a series of deaths and injuries caused by PCBs manufactured by Monsanto Chemical Company until 1977. The trial took nearly a month and the jury took a day of deliberations to return a verdict against the plaintiffs from throughout the USA.[73][74] Similar cases are ongoing. "The evidence simply doesn’t support the assertion that the historic use of PCB products was the cause of the plaintiffs’ harms. We are confident that the jury will conclude, as two other juries have found in similar cases, that the former Monsanto Company is not responsible for the alleged injuries,” a Monsanto statement said.[75]

In May 2016, a Missouri state jury ordered Monsanto to pay $46.5 million in a case where 3 plaintiffs claimed PCB exposure caused non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[76][77]

In December 2016, the state of Washington filed suit in King County. The state sought damages and clean up costs related to PCBs.[78][79] In March 2018 Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine also filed a lawsuit against Monsanto over health issues posed by PCBs.[80]

On November 21, 2019, a federal judge denied a bid by Monsanto to dismiss a lawsuit filed by LA County calling the company to clean up cancer-causing PCBs from Los Angeles County waterways and storm sewer pipelines.[81] The lawsuit calls for Monsanto to pay for cleanup of PCBs from dozens of waterways, including the LA River, San Gabriel River and the Dominguez Watershed.[81]

In June 2020, Bayer agreed to pay $650 million to settle local lawsuits related to Monsanto's pollution of public waters in various areas of the United States with PCBs.[9]

History

In 1865 the first "PCB-like" chemical was discovered, and was found to be a byproduct of coal tar. Years later in 1881, German chemists synthesized the first PCB in a laboratory. Between then and 1914, large amounts of PCBs were released into the environment, to the extent that there are still measurable amounts of PCBs in feathers of birds currently held in museums.[82]

In 1935, Monsanto Chemical Company (now Solutia Inc) took over commercial production of PCBs from Swann Chemical Company which had begun in 1929. PCBs, originally termed "chlorinated diphenyls", were commercially produced as mixtures of isomers at different degrees of chlorination. The electric industry used PCBs as a non-flammable replacement for mineral oil to cool and insulate industrial transformers and capacitors. PCBs were also commonly used as heat stabilizer in cables and electronic components to enhance the heat and fire resistance of PVC.[83]

In the 1930s, the toxicity associated with PCBs and other chlorinated hydrocarbons, including polychlorinated naphthalenes, was recognized because of a variety of industrial incidents.[84] Between 1936 and 1937, there were several medical cases and papers released on the possible link between PCBs and its detrimental health effects. In 1936 a U.S. Public health Service official described the wife and child of a worker from the Monsanto Industrial Chemical Company who exhibited blackheads and pustules on their skin. The official attributed these symptoms to contact with the worker's clothing after he returned from work. In 1937, a conference about the hazards was organized at Harvard School of Public Health, and a number of publications referring to the toxicity of various chlorinated hydrocarbons were published before 1940.[85]

In 1947 Robert Brown reminded chemists that Arochlors were "objectionably toxic. Thus the maximum permissible concentration for an 8-hr. day is 1 mg/m3 of air. They also produce a serious and disfiguring dermatitis".[86]

In 1954 Japan, Kanegafuchi Chemical Co. Ltd. (Kaneka Corporation) first produced PCBs, and continued until 1972.[10]

Through the 1960s Monsanto Chemical Company knew increasingly more about PCBs' harmful effects on humans and the environment, per internal leaked documents released in 2002, yet PCB manufacture and use continued with few restraints until the 1970s.[87]

In 1966, PCBs were determined by Swedish chemist Sören Jensen to be an environmental contaminant.[88] Jensen, according to a 1994 article in Sierra, named chemicals PCBs, which previously, had simply been called "phenols" or referred to by various trade names, such as Aroclor, Kanechlor, Pyrenol, Chlorinol and others. In 1972, PCB production plants existed in Austria, West Germany, France, the UK, Italy, Japan, Spain, the USSR and the US.[10]

In the early 1970s, Ward B. Stone of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) first published his findings that PCBs were leaking from transformers and had contaminated the soil at the bottom of utility poles.

There have been allegations that Industrial Bio-Test Laboratories engaged in data falsification in testing relating to PCBs.[89][90][91][92] In 2003, Monsanto and Solutia Inc., a Monsanto corporate spinoff, reached a US$700 million settlement with the residents of West Anniston, Alabama who had been affected by the manufacturing and dumping of PCBs.[65][66] In a trial lasting six weeks, the jury found that "Monsanto had engaged in outrageous behavior, and held the corporations and its corporate successors liable on all six counts it considered – including negligence, nuisance, wantonness and suppression of the truth."[67]

Existing products containing PCBs which are "totally enclosed uses" such as insulating fluids in transformers and capacitors, vacuum pump fluids, and hydraulic fluid, are allowed to remain in use.[93] The public, legal, and scientific concerns about PCBs arose from research indicating they are likely carcinogens having the potential to adversely impact the environment and, therefore, undesirable as commercial products. Despite active research spanning five decades, extensive regulatory actions, and an effective ban on their production since the 1970s, PCBs still persist in the environment and remain a focus of attention.[10]

Pollution due to PCBs

Belgium

In 1999, the Dioxin Affair occurred when 50 kg of PCB transformer oils were added to a stock of recycled fat used for the production of 500 tonnes of animal feed, eventually affecting around 2,500 farms in several countries.[94][95] The name Dioxin Affair was coined from early misdiagnosis of dioxins as the primary contaminants, when in fact they turned out to be a relatively small part of the contamination caused by thermal reactions of PCBs. The PCB congener pattern suggested the contamination was from a mixture of Aroclor 1260 & 1254. Over 9 million chickens, and 60,000 pigs were destroyed because of the contamination. The extent of human health effects has been debated, in part because of the use of differing risk assessment methods. One group predicted increased cancer rates, and increased rates of neurological problems in those exposed as neonates. A second study suggested carcinogenic effects were unlikely and that the primary risk would be associated with developmental effects due to exposure in pregnancy and neonates.[95] Two businessmen who knowingly sold the contaminated feed ingredient received two-year suspended sentences for their role in the crisis.[96]

Italy

The Italian company Caffaro, located in Brescia, specialized in producing PCBs from 1938 to 1984, following the acquisition of the exclusive rights to use the patent in Italy from Monsanto. The pollution resulting from this factory and the case of Anniston, in the US, are the largest known cases in the world of PCB contamination in water and soil, in terms of the amount of toxic substance dispersed, size of the area contaminated, number of people involved and duration of production.

The values reported by the local health authority (ASL) of Brescia since 1999 are 5,000 times above the limits set by Ministerial Decree 471/1999 (levels for residential areas, 0.001 mg/kg). As a result of this and other investigations, in June 2001, a complaint of an environmental disaster was presented to the Public Prosecutor's Office of Brescia. Research on the adult population of Brescia showed that residents of some urban areas, former workers of the plant, and consumers of contaminated food, have PCB levels in their bodies that are in many cases 10–20 times higher than reference values in comparable general populations.[97] PCBs entered the human food supply by animals grazing on contaminated pastures near the factory, especially in local veal mostly eaten by farmers' families.[98] The exposed population showed an elevated risk of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but not for other specific cancers.[99]

Japan

In 1968, a mixture of dioxins and PCBs got into rice bran oil produced in northern Kyushu. Contaminated cooking oil sickened more than 1860 people. The symptoms were called Yushō disease.[48]

In Okinawa, high levels of PCB contamination in soil on Kadena Air Base were reported in 1987 at thousands of parts per million, some of the highest levels found in any pollution site in the world.[100]

Republic of Ireland

In December 2008, a number of Irish news sources reported testing had revealed "extremely high" levels of dioxins, by toxic equivalent, in pork products, ranging from 80 to 200 times the EU's upper safe limit of 1.5 pg WHO-TEQDFP/μg i.e. 0.12 to 0.3 parts per billion.[101][102]

Brendan Smith, the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, stated the pork contamination was caused by PCB-contaminated feed that was used on 9 of Ireland's 400 pig farms, and only one feed supplier was involved.[101][103] Smith added that 38 beef farms also used the same contaminated feed, but those farms were quickly isolated and no contaminated beef entered the food chain.[104] While the contamination was limited to just 9 pig farms, the Irish government requested the immediate withdrawal and disposal of all pork-containing products produced in Ireland and purchased since 1 September 2008. This request for withdrawal of pork products was confirmed in a press release by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland on December 6.[105]

It is thought that the incident resulted from the contamination of fuel oil used in a drying burner at a single feed processor, with PCBs. The resulting combustion produced a highly toxic mixture of PCBs, dioxins and furans, which was included in the feed produced and subsequently fed to a large number of pigs.[106]

Kenya

In Kenya, a number of cases have been reported in the 2010s of thieves selling transformer oil, stolen from electric transformers, to the operators of roadside food stalls for use in deep frying. When used for frying, it is reported that transformer oil lasts much longer than regular cooking oil. The downside of this misuse of the transformer oil is the threat to the health of the consumers, due to the presence of PCBs.[107]

Slovakia

The chemical plant Chemko in Strážske (east Slovakia) was an important producer of polychlorinated biphenyls for the former communist bloc (Comecon) until 1984. Chemko contaminated a large part of east Slovakia, especially the sediments of the Laborec river and reservoir Zemplínska šírava.[108][109]

Slovenia

Between 1962 and 1983, the Iskra Kondenzatorji company in Semič (White Carniola, Southeast Slovenia) manufactured capacitors using PCBs. Due to the wastewater and improperly disposed waste products, the area (including the Krupa and Lahinja rivers) became highly contaminated with PCBs. The pollution was discovered in 1983, when the Krupa river was meant to become a water supply source. The area was sanitized then, but the soil and water are still highly polluted. Traces of PCBs were found in food (eggs, cow milk, walnuts) and Krupa is still the most PCB-polluted river in the world.

Spain

Several cetacean species have very high mean blubber PCB concentrations likely to cause population declines and suppress population recovery. Striped dolphins, bottlenose dolphins and killer whales were found to have mean levels that markedly exceeded all known marine mammal PCB toxicity thresholds. The western Mediterranean Sea and the south-west Iberian Peninsula were identified as “hotspots”.[110]

United Kingdom

Monsanto manufactured PCBs at its chemical plant in Newport, South Wales, until the mid- to late-1970s. During this period, waste matter, including PCBs, from the Newport site was dumped at a disused quarry near Groes-faen, west of Cardiff, and Penhros landfill site[111] from where it continues to be released in waste water discharges.[112]

United States

Only one company, Monsanto manufactured PCBs in the US. Its production was entirely halted in 1977. (Kimbrough, 1987, 1995)[8]

Alabama

PCBs originating from Monsanto Chemical Company in Anniston, Alabama were dumped into Snow Creek, which then spread to Choccolocco Creek, then Logan Martin Lake.[113] In the early 2000s, class action lawsuits were settled by local land owners, including those on Logan Martin Lake, and Lay Reservoir (downstream on the Coosa River), for the PCB pollution. Donald Stewart, former Senator from Alabama, first learned of the concerns of hundreds of west Anniston residents after representing a church which had been approached about selling its property by Monsanto. Stewart went on to be the pioneer and lead attorney in the first and majority of cases against Monsanto and focused on residents in the immediate area known to be most polluted. Other attorneys later joined in to file suits for those outside the main immediate area around the plant; one of these was the late Johnnie Cochran.

In 2007, the highest pollution levels remained concentrated in Snow and Choccolocco Creeks.[114] Concentrations in fish have declined and continue to decline over time; sediment disturbance, however, can resuspend the PCBs from the sediment back into the water column and food web.

Great Lakes

In 1976 environmentalists found PCBs in the sludge at Waukegan Harbor, the southwest end of Lake Michigan. They were able to trace the source of the PCBs back to the Outboard Marine Corporation that was producing boat motors next to the harbor. By 1982, the Outboard Marine Corporation was court-ordered to release quantitative data referring to their PCB waste released. The data stated that from 1954 they released 100,000 tons of PCB into the environment, and that the sludge contained PCBs in concentrations as high as 50%.[115][116]

In 1989, during construction near the Zilwaukee bridge, workers uncovered an uncharted landfill containing PCB-contaminated waste which required $100,000 to clean up.[117]

Much of the Great Lakes area were still heavily polluted with PCBs in 1988, despite extensive remediation work.[118]

Indiana

From the late 1950s through 1977, Westinghouse Electric used PCBs in the manufacture of capacitors in its Bloomington, Indiana, plant. Reject capacitors were hauled and dumped in area salvage yards and landfills, including Bennett's Dump, Neal's Landfill and Lemon Lane Landfill.[119] Workers also dumped PCB oil down factory drains, which contaminated the city sewage treatment plant.[120] The City of Bloomington gave away the sludge to area farmers and gardeners, creating anywhere from 200 to 2,000 sites, which remain unaddressed.

Over 2 million pounds of PCBs were estimated to have been dumped in Monroe and Owen counties. Although federal and state authorities have been working on the sites' environmental remediation, many areas remain contaminated. Concerns have been raised regarding the removal of PCBs from the karst limestone topography, and regarding the possible disposal options. To date, the Westinghouse Bloomington PCB Superfund site case does not have a Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study (RI/FS) and Record of Decision (ROD), although Westinghouse signed a US Department of Justice Consent Decree in 1985.[119] The 1985 consent decree required Westinghouse to construct an incinerator that would incinerate PCB-contaminated materials. Because of public opposition to the incinerator, however, the State of Indiana passed a number of laws that delayed and blocked its construction. The parties to the consent decree began to explore alternative remedies in 1994 for six of the main PCB contaminated sites in the consent decree. Hundreds of sites remain unaddressed as of 2014. Monroe County will never be PCB-free, as noted in a 2014 Indiana University program about the local contamination.[119]

On 15 February 2008, Monroe County approved a plan to clean up the three remaining contaminated sites in the City of Bloomington, at a cost of $9.6 million to CBS Corp., the successor of Westinghouse. In 1999, Viacom bought CBS, so they are current responsible party for the PCB sites.[121]

Massachusetts

Pittsfield, in western Massachusetts, was home to the General Electric (GE) transformer, capacitor, and electrical generating equipment divisions. The electrical generating division built and repaired equipment that was used to power the electrical utility grid throughout the nation. PCB-contaminated oil routinely migrated from GE's 254-acre (1.03 km2) industrial plant located in the very center of the city to the surrounding groundwater, nearby Silver Lake, and to the Housatonic River, which flows through Massachusetts, Connecticut, and down to Long Island Sound.[122] PCB-containing solid material was widely used as fill, including oxbows of the Housatonic River.[122] Fish and waterfowl who live in and around the river contain significant levels of PCBs and are not safe to eat.[123]

New Bedford Harbor, which is a listed Superfund site,[124] contains some of the highest sediment concentrations in the marine environment.[125]

Investigations into historic waste dumping in the Bliss Corner neighborhood have revealed the existence of PCBs, among other hazardous materials, buried into soil and waste material.[126]

Missouri

In 1982 Martha C. Rose Chemical Inc. began processing and disposing of materials contaminated with PCB's in Holden, Missouri, a small rural community about 40 miles east of Kansas City. From 1982 until 1986, nearly 750 companies, including General Motors Corp., Commonwealth Edison, Illinois Power Co. and West Texas Utilities, sent millions of pounds of PCB contaminated materials to Holden for disposal.[127] Instead, according to prosecutors, the company began storing the contaminated materials while falsifying its reports to the EPA to show they had been removed. After investigators learned of the deception, Rose Chemical was closed and filed for bankruptcy. The site had become the nation's largest waste site for the chemical PCB.[128] In the four years the company was operational, the EPA inspected it four times and assessed $206,000 in fines but managed to collect only $50,000.[129]

After the plant closed the state environmental agency found PCB contamination in streams near the plant and in the city's sewage treatment sludge. A 100,000 square-foot warehouse and unknown amounts of contaminated soil and water around the site had to be cleaned up. Most of the surface debris, including close to 13 million pounds of contaminated equipment, carcasses and tanks of contaminated oil, had to be removed.[130] Walter C. Carolan, owner of Rose Chemical, and five others pleaded guilty in 1989 to committing fraud or falsifying documents. Carolan and two other executives served sentences of less than 18 months; the others received fines and were placed on probation. Cleanup costs at the site are estimated at $35 million.[130]

New York

Pollution of the Hudson River is largely due to dumping of PCBs by General Electric from 1947 to 1977.[131] GE dumped an estimated 1.3 million pounds of PCBs into the Hudson River during these years.[132] This pollution caused a range of harmful effects to wildlife and people who eat fish from the river or drink the water.[133]

Love Canal is a neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York that was heavily contaminated with toxic waste including PCBs.[134] Eighteen Mile Creek in Lockport, New York is an EPA Superfund site for PCBs contamination.[135]

PCB pollution at the State Office Building in Binghamton was responsible for what is now considered to be the first indoor environmental disaster in the United States.[136] In 1981, a transformer explosion in the basement spewed PCBs throughout the entire 18-story building.[137] The contamination was so severe that cleanup efforts kept the building closed for 13 years.[138][139]

North Carolina

One of the largest deliberate PCB spills in American history occurred in the summer of 1978 when 31,000 gallons (117 m^3) of PCB-contaminated oil were illegally sprayed by the Ward PCB Transformer Company in 3-foot (0.91 m) swaths along the roadsides of some 240 miles (390 km) of North Carolina highway shoulders in 14 counties and at the Fort Bragg Army Base. The crime, known as "the midnight dumpings", occurred over nearly 2 weeks, as drivers of a black-painted tanker truck drove down one side of rural Piedmont highways spraying PCB-laden waste and then up the other side the following night.[140]

Under Governor James B. Hunt, Jr., state officials then erected large, yellow warning signs along the contaminated highways that read: "CAUTION: PCB Chemical Spills Along Highway Shoulders." The illegal dumping is believed to have been motivated by the passing of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which became effective on August 2, 1978 and increased the expense of chemical waste disposal.

Within a couple of weeks of the crime, Robert Burns and his sons, Timothy and Randall, were arrested for dumping the PCBs along the roadsides. Burns was a business partner of Robert "Buck" Ward, Jr., of the Ward PCB Transformer Company, in Raleigh. Burns and sons pleaded guilty to state and Federal criminal charges; Burns received a three to five-year prison sentence. Ward was acquitted of state charges in the dumping, but was sentenced to 18 months prison time for violation of TSCA.[141]

Cleanup and disposal of the roadside PCBs generated controversy, as the Governor's plan to pick up the roadside PCBs and to bury them in a landfill in rural Warren County were strongly opposed in 1982 by local residents.[141] In October 2013, at the request of the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC), the City of Charlotte, North Carolina decided to stop applying sewage sludge to land while authorities investigated the source of PCB contamination.[142] In February 2014, the City of Charlotte admitted PCBs have entered their sewage treatment centers as well.[143]

After the 2013 SCDHEC had issued emergency regulations[144] the City of Charlotte discovered high levels of PCBs entering its sewage waste water treatment plants, where sewage is converted to sewage sludge.[143] The city at first denied it had a problem, then admitted an "event" occurred in February 2014, and in April that the problem had occurred much earlier.[142][145] The city stated that its very first test with a newly changed test method revealed very high PCB levels in its sewage sludge farm field fertilizer. Because of the widespread use of the contaminated sludge, SCDHEC subsequently issued PCB fish advisories for nearly all streams and rivers bordering farm fields that had been applied with city waste.[146]

Ohio

The Clyde cancer cluster (also known as the Sandusky County cancer cluster) is a childhood cancer cluster that has affected many families in Clyde, Ohio and surrounding areas. PCBs were found in soil in a public park within the area of the cancer cluster.[147]

In Akron, Ohio, soil was contaminated and noxious PCB-laden fumes had been put into the air by an electrical transformer deconstruction operation from the 1930s to the 1960s.[148]

South Carolina

From 1955 until 1977, the Sangamo Weston plant in Pickens, SC, used PCBs to manufacture capacitors, and dumped 400,000 pounds of PCB contaminated wastewater into the Twelve Mile Creek. In 1990, the EPA declared the 228 acres (0.92 km2) site of the capacitor plant, its landfills and the polluted watershed, which stretches nearly 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) downstream to Lake Hartwell as a Superfund site. Two dams on the Twelve Mile Creek are to be removed and on Feb. 22, 2011 the first of two dams began to be dismantled. Some contaminated sediment is being removed from the site and hauled away, while other sediment is pumped into a series of settling ponds.[149][150]

In 2013, the state environmental regulators issued a rare emergency order, banning all sewage sludge from being land applied or deposited on landfills, as it contained very high levels of PCBs. The problem had not been discovered until thousands of acres of farm land in the state had been contaminated by the hazardous sludge. A criminal investigation to determine the perpetrator of this crime was launched.[151]

Washington

As of 2015, several bodies of water in the state of Washington were contaminated with PCBs, including the Columbia River, the Duwamish River, Green Lake, Lake Washington, the Okanogan River, Puget Sound, the Spokane River, the Walla Walla River, the Wenatchee River, and the Yakima River.[152] A study by Washington State published in 2011 found that the two largest sources of PCB flow into the Spokane River were City of Spokane stormwater (44%) and municipal and industrial discharges (20%).[153]

PCBs entered the environment through paint, hydraulic fluids, sealants, inks and have been found in river sediment and wild life. Spokane utilities will spend $300 million to prevent PCBs from entering the river in anticipation of a 2017 federal deadline to do so.[154] In August 2015 Spokane joined other U.S cities like San Diego and San Jose, California, and Westport, Massachusetts. in seeking damages from Monsanto.[155]

Wisconsin

From 1954 until 1971, the Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin had PCBs deposited into it from Appleton Paper/NCR, P.H. Gladfelter, Georgia Pacific and other notable local paper manufacturing facilities. The Wisconsin DNR estimates that after wastewater treatment the PCB discharges to the Fox River due to production losses ranged from 81,000 kg to 138,000 kg. (178,572 lbs. to 304,235 lbs). The production of Carbon Copy Paper and its byproducts led to the discharge into the river. Fox River clean up is ongoing.[156]

Pacific Ocean

Polychlorinated biphenyls have been discovered in organisms living in the Mariana trench in the Pacific Ocean. Levels were as high as 1,900 nanograms per gram of amphipod tissue in the organisms analyzed.[157]

Regulation

Japan

In 1972 the Japanese government banned the production, use, and import of PCBs.[10]

Sweden

In 1973, the use of PCBs in "open" or "dissipative" sources, such as plasticisers in paints and cements, casting agents, fire retardant fabric treatments and heat stabilizing additives for PVC electrical insulation, adhesives, paints and waterproofing, railroad ties was banned in Sweden.

United Kingdom

In 1981, the UK banned closed uses of PCBs in new equipment, and nearly all UK PCB synthesis ceased; closed uses in existing equipment containing in excess of 5 litres of PCBs were not stopped until December 2000.[158]

United States

In 1976, concern over the toxicity and persistence (chemical stability) of PCBs in the environment led the United States Congress to ban their domestic production, effective January 1, 1978, pursuant to the Toxic Substances Control Act.[159][160] To implement the law, EPA banned new manufacturing of PCBs, but issued regulations that allowed for their continued use in electrical equipment for economic reasons.[161] EPA began issuing regulations for PCB usage and disposal in 1979.[162] The agency has issued guidance publications for safe removal and disposal of PCBs from existing equipment.[163]

EPA defined the "maximum contaminant level goal" for public water systems as zero, but because of the limitations of water treatment technologies, a level of 0.5 parts per billion is the actual regulated level (maximum contaminant level).[164]

Methods of destruction

Physical

PCBs are technically attractive because of their inertness, which includes their resistance to combustion. Nonetheless, they can be effectively destroyed by incineration at 1000 °C. When combusted at lower temperatures, they convert in part to more hazardous materials, including dibenzofurans and dibenzodioxins. When conducted properly, the combustion products are water, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen chloride. In some cases, the PCBs are combusted as a solution in kerosene. PCBs have also been destroyed by pyrolysis in the presence of alkali metal carbonates.[2]

Thermal desorption is highly effective at removing PCBs from soil.[165]

Chemical

PCBs are fairly chemically unreactive, this property being attractive for its application as an inert material. They resist oxidation.[166] Many chemical compounds are available to destroy or reduce the PCBs. Commonly, PCBs are degraded by basis mixtures of glycols, which displace some or all chloride. Also effective are reductants such as sodium or sodium naphthenide.[2] Vitamin B12 has also shown promise.[167]

Microbial

Some micro-organisms degrade PCBs by reducing the C-Cl bonds. Microbial dechlorination tends to be rather slow-acting in comparison to other methods. Enzymes extracted from microbes can show PCB activity. In 2005, Shewanella oneidensis biodegraded a high percentage of PCBs in soil samples.[168] A low voltage current can stimulate the microbial degradation of PCBs.[169]

Fungal

There is research showing that some ligninolytic fungi can degrade PCBs.[170]

Homologs

For a complete list of the 209 PCB congeners, see PCB congener list. Note that biphenyl, while not technically a PCB congener because of its lack of chlorine substituents, is still typically included in the literature.

| PCB homolog | CASRN | Cl substituents |

Number of congeners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biphenyl (not a PCB) | 92-52-4 | 0 | 1 |

| Monochlorobiphenyl | 27323-18-8 | 1 | 3 |

| Dichlorobiphenyl | 25512-42-9 | 2 | 12 |

| Trichlorobiphenyl | 25323-68-6 | 3 | 24 |

| Tetrachlorobiphenyl | 26914-33-0 | 4 | 42 |

| Pentachlorobiphenyl | 25429-29-2 | 5 | 46 |

| Hexachlorobiphenyl | 26601-64-9 | 6 | 42 |

| Heptachlorobiphenyl | 28655-71-2 | 7 | 24 |

| Octachlorobiphenyl | 55722-26-4 | 8 | 12 |

| Nonachlorobiphenyl | 53742-07-7 | 9 | 3 |

| Decachlorobiphenyl | 2051-24-3 | 10 | 1 |

See also

- Bay mud

- Organochlorine compound

- Polybrominated biphenyl

- Zodiac, a novel by Neal Stephenson which involves PCBs and their impact on the environment.

References

- "Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Health.

- Rossberg, Manfred; Lendle, Wilhelm; Pfleiderer, Gerhard; Tögel, Adolf; Dreher, Eberhard-Ludwig; Langer, Ernst; Rassaerts, Heinz; Kleinschmidt, Peter; Strack (2006). "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2.

- Robertson, Larry W.; Hansen, Larry G., eds. (2001). PCBs: Recent advances in environmental toxicology and health effects. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 11. ISBN 978-0813122267.

- Porta, M.; Zumeta, E. (2002). "Implementing the Stockholm Treaty on Persistent Organic Pollutants". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 59 (10): 651–2. doi:10.1136/oem.59.10.651. PMC 1740221. PMID 12356922.

- "Health Effects of PCBs". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2016-09-15.

- "Dioxins and PCBs". European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Boas, Malene; Feldt-Rasmussen, Ulla; Skakkebaek, Niels; Main, Katharina (May 1, 2006). "Environmental chemicals and thyroid function". European Journal of Endocrinology. 154 (5): 599–611. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02128. PMID 16645005.

- "41 Polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans". Reproductive and developmental toxicology. Gupta, Ramesh C. London: Academic Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-12-382033-4. OCLC 717387050.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Chappell, Bill (24 June 2020). "Bayer To Pay More Than $10 Billion To Resolve Cancer Lawsuits Over Weedkiller Roundup". NPR. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- UNEP Chemicals (1999). Guidelines for the Identification of PCBs and Materials Containing PCBs (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- "PCB Transformers and Capacitors from management to Reclassification to Disposal" (PDF). chem.unep.ch. United Nations Environmental Program. pp. 55, 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-06-21. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- Kimbrough, R. D.; Jensen, A. A., eds. (2012). Halogenated Biphenyls, Terphenyls, Naphthalenes, Dibenzodioxins and Related Products. Elsevier. p. 24. ISBN 9780444598929.

- Identifying PCB-Containing Capacitors (PDF). Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council. 1997. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-642-54507-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- Safe, Stephen; Hutzinger, Otto (1984). "Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBBs): Biochemistry, Toxicology, and Mechanism of Action". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 13 (4): 319–395. doi:10.3109/10408448409023762. PMID 6091997.

- Safe, Stephen; Bandiera, Stelvio; Sawyer, Tom; Robertson, Larry; Safe, Lorna; et al. (1985). "PCBs: Structure-Function Relationships and Mechanism of Action". Environmental Health Perspectives. 60: 47–56. doi:10.1289/ehp.856047. JSTOR 3429944. PMC 1568577. PMID 2992927.

- Winneke, Gerhard; Bucholski, Albert; Heinzow, Birger; Krämer, Ursula; Schmidt, Eberhard; Wiener, J. A.; Steingrüber, H. J.; et al. (1998). "Developmental neurotoxicity of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBS): Cognitive and psychomotor functions in 7-month old children". Toxicology Letters. 102–103: 423–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(98)00334-8. PMID 10022290.

- National Research Council (United States) (2001). A Risk Management Strategy for PCB-Contaminated Sediments. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10041. ISBN 978-0-309-07321-9.

- Simon, Ted; Britt, Janice K.; James, Robert C. (2007). "Development of a neurotoxic equivalence scheme of relative potency for assessing the risk of PCB mixtures". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 48 (2): 148–170. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.03.005. PMID 17475378.

- Chauhan, K.; Kodavanti, P. R.; McKinney, J. D. (2000). "Assessing the Role of ortho-Substitution on Polychlorinated Biphenyl Binding to Transthyretin, a Thyroxine Transport Protein". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 162 (1): 10–21. doi:10.1006/taap.1999.8826. PMID 10631123.

- "Proceedings of the Subregional Awareness Raising Workshop on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), Bangkok, Thailand". United Nations Environment Programme. 25 November 1997. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- "Brand names of PCBs — What are PCBs?". Japan Offspring Fund / Center for Marine Environmental Studies (CMES), Ehime University, Japan. 2003. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Erickson, Mitchell D.; Kaley, II, Robert G. (2011). "Applications of polychlorinated biphenyls" (PDF). Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. Springer-Verlag. 18 (2): 135–51. doi:10.1007/s11356-010-0392-1. PMID 20848233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Erickson, Mitchell D.; Kaley, Robert G. (17 September 2010). "Applications of polychlorinated biphenyls". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 18 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1007/s11356-010-0392-1. PMID 20848233.

- Breivik, K.; Sweetman, A.; Pacyna, J.; Jones, K. (2002). "Towards a global historical emission inventory for selected PCB congeners — a mass balance approach: 1. Global production and consumption". The Science of the Total Environment. 290 (1–3): 181–98. Bibcode:2002ScTEn.290..181B. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(01)01075-0. PMID 12083709.

- Godish, T. (2001). Indoor environmental quality (1st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers. pp. 110–30.

- Pivnenko, K.; Olsson, M. E.; Götze, R.; Eriksson, E.; Astrup, T. F. (2016). "Quantification of chemical contaminants in the paper and board fractions of municipal solid waste" (PDF). Waste Management. 51: 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.03.008. PMID 26969284.

- Rudel, Ruthann A.; Seryak, Liesel M.; Brody, Julia G. (2008). "PCB-containing wood floor finish is a likely source of elevated PCBs in residents' blood, household air and dust: A case study of exposure". Environmental Health. 7: 2. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-7-2. PMC 2267460. PMID 18201376.

- Grossman, Elizabeth (2013-03-01). "Nonlegacy PCBs: Pigment Manufacturing By-Products Get a Second Look". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (3): a86–a93. doi:10.1289/ehp.121-a86. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 3621189. PMID 23454657.

- "Nasty chemicals abound in what was thought an untouched environment". The Economist. 2017-02-18. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Wethington, David M.; Hornbuckle, Keri C. (2005). "Milwaukee, WI, as a Source of Atmospheric PCBs to Lake Michigan". Environmental Science & Technology. 39 (1): 57–63. Bibcode:2005EnST...39...57W. doi:10.1021/es048902d. PMID 15667075.

- Jamshidi, Arsalan; Hunter, Stuart; Hazrati, Sadegh; Harrad, Stuart (2007). "Concentrations and Chiral Signatures of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Outdoor and Indoor Air and Soil in a Major U.K. Conurbation". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (7): 2153–2158. Bibcode:2007EnST...41.2153J. doi:10.1021/es062218c. PMID 17438756.

- Christian Schmidt; Tobias Krauth; Stephan Wagner (2017). "Export of plastic debris by rivers into the sea". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–12253. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. PMID 29019247.

- Inês Ferreira; Cátia Venâncio; Isabel Lopes; Miguel Oliveira (2019). "Nanoplastics and Marine Organisms: What Has Been Studied?". Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 67: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2019.01.006. PMID 30685594. Retrieved 2019-12-01 – via login.libproxy.unm.edu.

- ma, Piao; Wang, mu Wei; Liu, Hui; Chen, yu Feng; Xia, Jihong (2019-01-01). "Research on ecotoxicology of microplastics on freshwater aquatic organisms". Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability. 31 (1): 131–137. doi:10.1080/26395940.2019.1580151. ISSN 2639-5932.

- Faber, Harold (October 8, 1981). "Hunters who eat ducks warned on PCB hazard". New York Times.

- Rapp Learn, Joshua (November 30, 2015). "Seabirds Are Dumping Pollution-Laden Poop Back on Land". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Richardson, Kristine L. (2011). "Biotransformation of 2,2′,5,5′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 52) and 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB 77) by Liver Microsomes from Four Species of Sea Turtles". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 24 (5): 718–725. doi:10.1021/tx1004562. PMID 21480586.

- Forgue, S. T.; Preston, B. D.; Hargraves, W. A.; Reich, I. L.; Allen, J. R. (1979). "Direct evidence that an arene oxide is a metabolic intermediate of 2,2′,5,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 91 (2): 475–483. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(79)91546-8. PMID 42397.

- Parke, D. V. (1985). "The role of cytochrome P-450 in the metabolism of pollutants". Environmental Research. 17 (2–4): 97–100. doi:10.1016/0141-1136(85)90049-2.

- McFarland, V. A.; Clarke, J. U. (1989). "Environmental occurrence, abundance, and potential toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners—Considerations for a congener-specific analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 81: 225–239. doi:10.1289/ehp.8981225. PMC 1567542. PMID 2503374.

- Paterson, Gordon (2007). "PCB Elimination by Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) during an Annual Temperature Cycle". Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (3): 824–829. Bibcode:2007EnST...41..824P. doi:10.1021/es060266r. PMID 17328189.

- Hoekstra, Paul F. (2002). "Enantiomer-Specific Accumulation of PCB Atropisomers in the Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus)". Environmental Science & Technology. 36 (7): 1419–1425. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.1419H. doi:10.1021/es015763g. PMID 11999046.

- Van den Berg, Martin; Birnbaum, Linda; Bosveld, Albertus T. C.; Brunström, Björn; Cook, Philip; et al. (1998). "Toxic Equivalency Factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDFs for Humans and Wildlife". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106 (12): 775–792. doi:10.1289/ehp.98106775. JSTOR 3434121. PMC 1533232. PMID 9831538.

- Crinnion, Walter (March 2011). "Polychlorinated Biphenyls: Persistent Pollutants with Immunological, Neurological, and Endocrinological Consequences" (PDF). Environmental Medicine. 16 (1): 5–13. PMID 21438643. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- "Public Health Statement for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)". Toxic Substances Portal. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2015-01-21.

- Purdue University; EPA (n.d.). "Exploring the Great Lakes. Bioaccumulation/Biomagnification Effects" (PDF). Chicago, IL: EPA. p. 2. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Steingraber, Sandra (2001). "12". Having Faith : an ecologist's journey to motherhood (Berkley trade pbk. ed.). New York: Berkley. ISBN 978-0425189993.

- Aoki, Yasunobu (May 2001). "Polychlorinated Biphenyls, Polychloronated Dibenzo-p-dioxins, and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans as Endocrine Disrupters—What We Have Learned from Yusho Disease". Environmental Research. 86 (1): 2–11. Bibcode:2001ER.....86....2A. doi:10.1006/enrs.2001.4244. PMID 11386736.

- "Yusho Disease."Disease ID 8326 at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases U.S. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center, National Institutes of Health. Gaithersburg, MD.

- "PCB Baby Studies Part 2". www.foxriverwatch.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- "Environmental Diseases from A to Z". Archived from the original on 15 March 2006.

- Jacobson, Joseph L.; Jacobson, Sandra W. (12 September 1996). "Intellectual Impairment in Children Exposed to Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Utero". New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (11): 783–789. doi:10.1056/NEJM199609123351104. PMID 8703183.

- Stewart, Paul; Reihman, Jacqueline; Lonky, Edward; Darvill, Thomas; Pagano, James (January 2000). "Prenatal PCB exposure and neonatal behavioral assessment scale (NBAS) performance". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 22 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1016/S0892-0362(99)00056-2. PMID 10642111.

- "PCBs: toxicity treatment and management". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, CDC. 1 September 2000.

- Winneke, G. (September 2011). "Developmental aspects of environmental neurotoxicology: lessons from lead and polychlorinated biphenyls". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 308 (1–2): 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.020. PMID 21679971.

- Schell, L. M. (March 2014). "Relationships of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p′-DDE) with Testosterone Levels in Adolescent Males". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (3): 304–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205984. PMC 3948020. PMID 24398050.

- Hagmar, Lars; Rylander, Lars; Dyremark, Eva; Klasson-Wehler, Eva; Erfurth, Eva Marie (10 April 2001). "Plasma concentrations of persistent organochlorines in relation to thyrotropin and thyroid hormone levels in women". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 74 (3): 184–188. doi:10.1007/s004200000213. PMID 11355292.

- "Contamination of rice bran oil with PCB used as the heating medium by leakage through penetration holes at the heating coil tube in deodorization chamber". Hatamura Institute for the Advancement of Technology. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- Goldey, E.S.; Kehn, L.S.; Lau, C.; Rehnberg, G.L.; Crofton, K.M. (November 1995). "Developmental Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (Aroclor 1254) Reduces Circulating Thyroid Hormone Concentrations and Causes Hearing Deficits in Rats". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 135 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1006/taap.1995.1210. PMID 7482542.

- Lauby-Secretan, Béatrice; Loomis, Dana; Grosse, Yann; El Ghissassi, Fatiha; Bouvard, Veronique; Benbrahim-Tallaa, Lamia; Guha, Neela; Baan, Robert; Mattock, Heidi; Straif, Kurt; on behalf of the International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group, Lyon, France (March 15, 2013). "Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls". Lancet Oncology. 14 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70104-9. PMID 23499544.

- Kramer, Shira; Hikel, Stephanie Moller; Adams, Kristen; Hinds, David; Moon, Katherine (2012). "Current Status of the Epidemiologic Evidence Linking Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and the Role of Immune Dysregulation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (8): 1067–75. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104652. PMC 3440083. PMID 22552995.

- Robert Steyer. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. November 25, 1991. "Settlement Doesn't End Monsanto's Woes". Accessed via Factiva July 12, 2020.

- Decision, Supreme Court of Kentucky. Monsanto Company v. Reed; Monsanto Company, Appellant, v. William Reed, et al., Appellees. Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Appellant, v. Monsanto Company, et al., Appellees. Nos. 95-SC-549-DG, 95-SC-561-DG. April 24, 1997

- Decision, Supreme Court of Florida. High v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp. 610 So.2d 1259 (1992) June 11, 1992

- "$700 Million Settlement in Alabama PCB Lawsuit". The New York Times. 21 August 2003. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Ala. SC makes ruling in cases over $300M Monsanto settlement". Legal Newsline. May 1, 2012. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013.

- Crean, Ellen (November 2007). "Toxic Secret Alabama Town Was Never Warned Of Contamination". CBS News. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Andrew Scurria (22 May 2014). "Jury Finds Monsanto PCBs Not To Blame For Cancer Cases". Law360. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Payton, Mari (21 August 2015). "City of San Diego Sues Monsanto Over PCB Pollution". NBC 7 San Diego. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Spokane sues Monsanto over Spokane River contamination". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. 3 August 2015.

- "City of San Jose Files Lawsuit Against Monsanto Over PCB Contamination Flowing Into San Francisco Bay, Represented by Environmental Law Firms Baron & Budd and Gomez Trial Attorneys". Reuters. August 3, 2015.

- Johnson, Eric M. (August 4, 2015). "Spokane, Washington, sues Monsanto over PCBs in polluted state river". Reuters. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Tim Barker (11 June 2015). "Monsanto PCB lawsuit set to begin in St. Louis County". St Louis Post-Despatch. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- Tim Barker (7 July 2015). "Monsanto prevails in PCB lawsuit". St Louis Post-Despatch. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Barker, Tim (October 1, 2015). "Monsanto faces another PCB trial in St. Louis". St Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Currier, Joel (May 26, 2016). "St. Louis jury orders Monsanto to pay $46.5 million in latest PCB lawsuit". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Parker, Stan. "Monsanto Plans $280M for PCB Personal Injury Settlements". Law360.com. Law360. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "AG Ferguson makes Washington first state to sue Monsanto over PCB damages, cleanup cost | Washington State".

- http://agportal-s3bucket.s3.amazonaws.com/uploadedfiles/Another/News/Press_Releases/WA_Complaint_FINALnew.pdf

- "Monsanto concealed effects of toxic chemical for decades, Ohio AG says in suit".

- https://www.courthousenews.com/judge-advances-la-countys-spat-with-monsanto-over-pcbs-cleanup/

- Riseborough, Robert; Brodine, Virginia (1971). "More Letters in the Wind". In Novick, Sheldon; Cottrell, Dorothy (eds.). Our world in peril: an Environment review. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett. pp. 243–55.

- Black Kaley, Karlyn; Carlisle, Jim; Siegel, David; Salinas, Julio (October 2006). Health Concerns and Environmental Issues with PVC-Containing Building Materials in Green Buildings (PDF). Integrated Waste Management Board, California Environmental Protection Agency. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Drinker, C. K.; Warren, M. F.; Bennet, G. A. (1937). "The problem of possible systemic effects from certain chlorinated hydrocarbons". Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 19 (7): 283–311.

- Butler, David A. (2005). "Connections: The Early History of Scientific and Medical Research on 'Agent Orange'" (PDF). Journal of Law and Policy. 13 (2): 527–542. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-09-23.

- Brown, R. M. (1947). "The toxicity of the 'Arochlors'". Chemist-Analyst. 36: 33.

- Grunwald, Michael (January 1, 2002). "Monsanto Hid Decades Of Pollution; PCBs Drenched Ala. Town, But No One Was Ever Told". The Washington Post.

- Jensen, S. (1966). "Report of a new chemical hazard". New Scientist. 32: 612.

- Coppolino, Eric Francis; Lanner, Hilary; Shawley, Brenda (September–October 1994). Rauber, Paul (ed.). "Pandora's poison". Sierra. Vol. 79 no. 5. p. 40. Archived from the original on 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- Robin, Marie-Monique (2010). "PCBs: White-Collar Crime". The World According to Monsanto: Pollution, Corruption, and the Control of the World's Food Supply. The New Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1595584267.

- Hughes, Jon; Thomas, Pat (2007-10-11). "Burying The Truth, the original Ecologist investigation into Monsanto and Brofiscin Quarry". The Ecologist. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- Steyer, Robert (1991-10-29). "Lab Falsified Monsanto PCB Data, Witness Says". St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

- "Dioxin Dorms – SUNY New Paltz :: SUNY Dorm Tests Toxic :: By Eric Francis :: Published by Planet Waves". dioxindorms.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Bernard A, Broeckaert F, De Poorter G, De Cock A, Hermans C, Saegerman C, Houins G (2002). "The Belgian PCB/dioxin incident: analysis of the food chain contamination and health risk evaluation". Environ. Res. 88 (1): 1–18. Bibcode:2002ER.....88....1B. doi:10.1006/enrs.2001.4274. PMID 11896663.

- Covaci A, Voorspoels S, Schepens P, Jorens P, Blust R, Neels H (2008). "The Belgian PCB/dioxin crisis-8 years later An overview". Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 25 (2): 164–70. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.003. PMID 21783853.

- "Dioxin scandal: 2 year suspended prison sentence". www.expatica.com. 2009-02-05. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Turrio-Baldassarri, Luigi; et al. (2008). "PCDD/F and PCB in human serum of differently exposed population groups of an Italian city". Chemosphere. 73 (1): S228–S234. Bibcode:2008Chmsp..73S.228T. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.081. PMID 18514762.

- La Rocca C, Mantovani A (2006). "From environment to food: the case of PCB". Annali-Istituto Superiore di Sanita. 42 (4): 410–6. PMID 17361063.

- Zani C, Toninelli G, Filisetti B, Donato F (2013). "Polychlorinated biphenyls and cancer: an epidemiological assessment". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C. 31 (2): 99–144. doi:10.1080/10590501.2013.782174. PMID 23672403.

- Jon Mitchell (March 17, 2014). "U.S. military report suggests cover-up over toxic pollution in Okinawa". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- "Food body to meet on pork recall". BBC. BBC. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs". Official Journal of the European Union. Brussels: European Union. 9 December 2006.

- "Firm at centre of toxin scare investigated". RTE news. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Q&A: The recall of Irish pork". BBC. 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- "Recall of Pork and Bacon Products December 2008" (Press release). Food Safety Authority of Ireland. December 2008. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- "Report of the Inter-Agency Review Group on the Dioxin Contamination Incident in Ireland in December 2008" (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine. Dec 2009.

- Iraki, XN. "Thieves fry Kenya's power grid for fast food". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Himič, Dan (2009). "Viete, čo doma dýchate?" [Do you know what you breathe at home?]. Život (in Slovak) (33).

- "Chemko Strážske" (in Slovak). Greenpeace. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011.

- Paul D. Jepson; et al. (2016). "PCB pollution continues to impact populations of orcas and other dolphins in European waters". Scientific Reports. 6: 18573. Bibcode:2016NatSR...618573J. doi:10.1038/srep18573. PMC 4725908. PMID 26766430.

- "Tip fumes "felt like terror attack"". WalesOnline. Media Wales Ltd. June 30, 2004.

- Levitt, Tom (21 February 2011). "Monsanto agrees to clean up toxic chemicals in South Wales quarry". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- "Anniston PCB Site (Monsanto Co), Anniston, AL". Superfund Site Profile. Atlanta, GA: EPA. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Rypel, Andrew L.; Findlay, Robert H.; Mitchell, Justin B.; Bayne, David R. (2007). "Variations in PCB concentrations between sexes of six warmwater fish species in Lake Logan Martin, Alabama, USA". Chemosphere. 68 (9): 1707–15. Bibcode:2007Chmsp..68.1707R. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.03.046. PMID 17490714.

- Ashworth, William (1987). The Late, Great Lakes. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1887-4.

- Mahan, Meegan L. (May 4, 1998). "Are PCBs still a problem in the great lakes?". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.

- Christopher J. Bessert. "Michigan Highways: In Depth: The Milwaukee Bridge". michiganhighways.org.

- Hileman, Bette (February 8, 1988). "Great Lakes Cleanup Effort". Chemical and Engineering News. 66 (6): 22–39. doi:10.1021/cen-v066n006.p022.

- "US EPA Region 5 Superfund". Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- "Westinghouse/ABB Plant Facility". 2006. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- "Monroe Co. approves PCB clean up". IndyStar.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- "GE/Housatonic River Site in New England: Site History and Description". USEPA. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "Rest of River of the GE-Pittsfield/Housatonic River Site". 2015-06-25. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Find New England Sites – New Bedford Site". EPA.

- "New Bedford Harbor, MA – Northeast Region – DARRP". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2010-10-20.