Architecture of Denmark

The architecture of Denmark has its origins in the Viking period, richly revealed by archaeological finds. It became firmly established in the Middle Ages when first Romanesque, then Gothic churches and cathedrals sprang up throughout the country. It was during this period that, in a country with little access to stone, brick became the construction material of choice, not just for churches but also for fortifications and castles.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Denmark |

|---|

|

Under the influence of Frederick II and Christian IV, both of whom had been inspired by the castles of France, Dutch and Flemish designers were brought to Denmark, initially to improve the country's fortifications, but increasingly to build magnificent royal castles and palaces in the Renaissance style. In parallel, the half-timbered style became popular for ordinary dwellings in towns and villages across the country.

Late in his reign, Christian IV also became an early proponent of Baroque which was to continue for a considerable time with many impressive buildings both in the capital and the provinces. Neoclassicism came initially from France but was slowly adopted by native Danish architects who increasingly participated in defining architectural style. A productive period of Historicism ultimately merged into the 19th century National Romantic style.

It was not, however, until the 1960s that Danish architects entered the world scene with their highly successful Functionalism. This, in turn, has evolved into more recent world-class masterpieces such as the Sydney Opera House and the Great Belt Bridge paving the way for a number of Danish designers to be rewarded for excellence both at home and abroad.

Middle Ages

Viking Age

Archaeological excavations in various parts of Denmark have revealed much about the way the Vikings lived. One of the most notable sites is Hedeby. Located some 45 km (28 mi) south of the Danish border near the German town of Schleswig, it probably dates back to the end of the 8th century. The houses are deemed to be among the most sophisticated dwellings of their time. Oak frames were used for the walls, and the roofs were probably thatched.[1]

Viking ring houses, such as those at Trelleborg, near Slagelse on the Danish island of Zealand, have a rather different, ship-like shape, the long walls bulging outwards. Each house consisted of a large central hall, 18 m × 8 m (59 ft × 26 ft) and two smaller rooms, one at each end. Those at Fyrkat (c. 980) in the north of Jutland were 28.5 m (94 ft) long, 5 m (16 ft) wide at the ends and 7.5 m (25 ft) in the middle, the long walls curving slightly outwards. The walls consisted of double rows of posts with planks wedged horizontally between them. A series of outer posts slanted towards the wall were possibly used to support the building like buttresses.[2]

Romanesque style

Denmark's first churches from the 9th century were built of timber and have not survived. Hundreds of stone churches in the Romanesque style were built in the 12th and 13th centuries. They had a flat-ceilinged nave and chancel with small rounded windows and round arches. Granite boulders and limestone were initially the preferred building materials, but after brick production reached Denmark in the middle of the 12th century, brick quickly became the material of choice.[3] Among the finest examples of brick Romanesque buildings are St. Bendt's Church in Ringsted (c. 1170)[4] and the unique Church of Our Lady in Kalundborg (c. 1200) with its five tall towers.[5]

The church at Østerlars on the island of Bornholm was built around 1150. Like three other churches on the island, it is a round church. The three-storeyed building is supported by a circular outer wall and an exceptionally wide, hollow central column.[6]

Construction of Lund Cathedral in Scania started in about 1103 when the region was part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It was the first of great Danish Romanesque cathedrals in the shape of a three-aisled basilica with transepts. It seems to have been related to earlier German buildings, though there are also traces of Anglo-Norman and Lombard influences.[7] Ribe, which followed with its great cathedral (1150–1250), had close trade contacts with the Rhine region of Germany. Both the materials, sandstone and tufa, and the models were taken from there.[8]

Gothic style

Towards the end of the 13th century and until about 1500, the Gothic style became the norm with the result that most of the older Romanesque churches were rebuilt or adapted to the Gothic style. The flat ceilings were replaced by high cross vaults, windows were enlarged with pointed arches, chapels and towers were added and the interiors were decorated with murals.[9] Red brick was the material of choice as can be seen in St. Canute's Cathedral, Odense (1300–1499), and St. Peter's Church, Næstved. St. Canute's presents all the features of Gothic architecture: pointed arch, buttresses, ribbed vaulting, increased light and the spatial combination of nave and chancel.

Although most Gothic architecture in Denmark is to be found in churches and monasteries, there are examples in the secular field too. Glimmingehus (1499–1506), a rectangular castle in Scania, clearly presents Gothic features. It was commissioned by the Danish nobleman Jens Holgersen Ulfstand who called on the services of Adam van Düren, a North German master who also worked on Lund Cathedral. The building contains many defensive features of the times, including parapets, false doors, dead-end corridors, murder-holes for pouring boiling pitch over the attackers, moats, drawbridges and various other death traps to protect the nobles against peasant uprisings.[10]

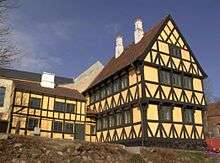

Half-timbered buildings

During the late Middle Ages, a slow transition began from the traditional wooden houses in towns and villages towards half-timbered properties. One of the oldest in Denmark is Anne Hvides Gård, a two-storeyed townhouse in Svendborg on the island of Funen, which was constructed in 1560.[11] The building now forms part of the Svendborg Museum.

Ystad in the southern Swedish region of Scania which was formerly part of Denmark still has some 300 half-timbered houses, several of them of historic importance.[12] The oldest surviving half-timbered house in Denmark, built in 1527, is located in Køge on the east coast of Sealand.

The Old Town in Aarhus, Jutland, is an open-air village museum consisting of 75 historical buildings collected from all parts of the country. They include a variety of half-timbered houses, some dating back to the middle of the 16th century.[13]

Romanesque Østerlars Church, Bornholm (1150)

Romanesque Østerlars Church, Bornholm (1150) The Gothic St. Canute's Cathedral, Odense (1300)

The Gothic St. Canute's Cathedral, Odense (1300) Gothic castle: Glimmingehus (1506)

Gothic castle: Glimmingehus (1506) Roskilde Cathedral with Romanesque and Gothic features (1175–1460)

Roskilde Cathedral with Romanesque and Gothic features (1175–1460)

Renaissance

Renaissance architecture thrived during the reigns of Frederick II and especially Christian IV. Inspired by the French castles of the times, Flemish architects designed masterpieces such as Kronborg Castle in Helsingør and Frederiksborg Palace in Hillerød. In Copenhagen, Rosenborg Castle (1606–24) and Børsen or the former stock exchange (1640) are perhaps the city's most remarkable Renaissance buildings.

During the reign of Frederick II, Kronborg Castle was designed by two Flemish architects, Hans Hendrik van Paesschen who started the work in 1574 and Anthonis van Obbergen who finished it in 1585. Modelled on a three-winged French castle, it was finally completed as a full four-winged building. The castle burnt down in 1629 but, under orders from Christian IV, was quickly rebuilt under the leadership of Hans van Steenwinckel the Younger, son of the famous Flemish artist. It is widely recognized as one of Europe's most outstanding Renaissance castles and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[14]

Frederiksborg Palace (1602–20) in Hillerød is the largest Renaissance palace in Scandinavia. Christian IV had most of Frederick II's original building pulled down in order to have van Steenwinckel complete a three-winged French-styled castle with a low terrace wing around a courtyard. The architectural expression and the decorative finish clearly reflect Dutch Renaissance preferences as evidenced by the ornamental portals and windows and especially in sweeping Italianate gables.[8]

Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen, also built by Christian IV, is another example of the Dutch Renaissance style. In 1606, the king first had a two-storey summerhouse built on a site he used as a park for relaxation. He then decided to start work on a much more ambitious building, the castle, which developed in stages until a Dutch Renaissance masterpiece was completed in 1624. Predating the castle, the Renaissance-style park, is Denmark's oldest royal garden.[15]

Sponsored by Christian IV, Børsen, one of the first commodity exchanges in Europe, was built from 1618 to 1624. It was designed to emphasize Copenhagen's position as a commercial metropolis. Although inspired by the Dutch Renaissance style, the distinctive towers and garrets on the roof reflect the taste of Christian IV. The characteristic spire of the building with four intertwined dragon tails topped by three crowns, symbolises the then Kingdom of Denmark, which included Norway and Sweden.[16]

In 1614, Christian IV began work on the construction of the then Danish Kristianstad in Scania, now in the south of Sweden, completing many of its buildings in the Renaissance style. Particularly impressive is the Church of the Trinity (1618–28) designed by Flemish-Danish architect Lorenz van Steenwinckel. It is said to be Scandinavia's finest example of a Renaissance church.

Christian IV also initiated a number of projects in Norway that were largely based on Renaissance architecture[17] He established mining operations in Kongsberg and Røros, now a World Heritage Site. After a devastating fire in 1624, the town of Oslo was moved to a new location and rebuilt as a fortified city with an orthogonal layout surrounded by ramparts, and renamed Christiania. King Christian also founded the trading city of Kristiansand, once again naming it after himself.

While stone buildings became more and more common as town houses, farms continued to be half-timbered, sometimes in conjunction with a single stone house. Ordinary people continued to live in half-timbered houses.

Holbæk in northwestern Sealand began to develop towards the end of the Middle Ages. Prosperity peaked in the 17th century as corn grown locally was traded with Germany and the Netherlands. The half-timbered houses which now form the museum date back to that period, providing an insight into how the town functioned at the time.[18]

Danish country vicarages from this period tended to be built in the same style as farmhouses, though usually rather larger. A fine example is Kølstrup Vicarage near Kerteminde in north-eastern Funen. The house itself is a thatched half-timbered building with a large rectangular courtyard flanked by outhouses.[19]

Baroque

As during the Renaissance period, it was again principally Dutch influence which predominated in Baroque architecture, although many of the features originated in Italy and France. Symmetry and regularity were primary concerns, often enhanced by a projecting central section on the main façade.

Copenhagen's Round Tower was also one of Christian IV's projects after he provided funding for an observatory as proposed by the astronomer Tycho Brahe. Under the initial leadership of Hans van Steenwinckel who surprisingly adapted the design to Dutch Baroque, the Tower was completed in 1642 with a height of almost 40 m. The bricks, specially ordered from the Netherlands, were of a hard-burned, slender type, known as muffer or mopper.[20] A 210-meter-long spiral ramp leads to the top, providing panoramic views over Copenhagen. The Round Tower is the oldest functioning observatory in Europe. Until 1861 it was used by the University of Copenhagen, but today, anyone can observe the night sky through the tower's astronomical telescope during the winter.[21]

Nysø Manor (1673) near Præstø, Sealand, was built for the local functionary Jens Lauridsen. It was the first Baroque country house in Denmark, replacing the earlier Renaissance style. The inspiration came from Holland and the architect was probably Ewert Janssen.[22]

One of the foremost designers of the times was the Danish architect Lambert van Haven whose masterpiece was the Church of Our Saviour, Copenhagen (1682–96) which relies on the Greek cross for its basic layout. The façade is segmented by Tuscan pilasters extending up to the full height of the building. Other features such as the distinctive corkscrew spire were however not undertaken until the reign of Frederick V. It was Lauritz de Thurah who finally completed the building in 1752.[23]

Charlottenborg (1672–83), on Kongens Nytorv in the centre of Copenhagen, is said to be the most important pure Baroque building remaining in Denmark. Van Haven may have been involved in its design although Ewert Janssen is usually credited with the work. Several other mansion houses in Denmark have been based on its design.[24]

It was Henrik Ruse, a Dutch building engineer, who was charged by Frederick III to develop the area around Kongens Nytorv, especially in connection with the Nyhavn Canal which was designed to become Copenhagen's new harbour. It was not, however, until Christian V became king in 1670 that Niels Rosenkrantz completed the work. Over the next few years, numerous town houses were built along the northern or sunny side of the canal. The oldest, Number 9, was completed in 1681, probably by Christen Christensen, the harbour master.[25]

Clausholm Castle (1693–94) near Randers was designed by the Danish architect Ernst Brandenburger with assistance of the Swede Nicodemus Tessin who was invited to decorate the facade.[26] The more sophisticated first-floor apartments with their higher ceilings were designed for use by royalty.

The first Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen, designed by Elias David Häusser and completed in the 1740s, was certainly one of the most impressive Baroque buildings of its day. Although the palace itself was destroyed by fire in 1794, the extensive showgrounds and riding arena completed by Niels Eigtved have survived undamaged and can be visited today.[27] Fredensborg Palace (1731), the royal residence on the shore of Sealand's Lake Esrum, with its exquisite Chancellery House, is the work of Johan Cornelius Krieger who was the court gardener at Rosenborg Castle.[28] The park at Fredensborg is one of Denmark's largest and best preserved Baroque gardens.[29]

After the turn of the 18th century, architecture developed into the late Baroque style. Among the major proponents were Johan Conrad Ernst who built the Chancery Building[30] or Kancellibygningen (1721) on Slotsholmen and Lauritz de Thurah who designed the Eremitage Palace (1734) in Dyrehaven, just north of Copenhagen. Even more ambitious was de Thurah's work at Ledreborg near Roskilde, where he succeeded in working the components into a well-balanced and cohesive Baroque palace.[31]

Rococo

Following on closely from the Baroque period, Rococo came into fashion in the 1740s under the leadership of Nicolai Eigtved. Originally a gardener, Eigtved spent many years abroad where he became increasingly interested in architecture, especially the French Rococo style. On his return to Denmark, he built Prinsens Palæ (1743–44) in Copenhagen as a residence for Crown Prince Frederick (later Frederick V). It is now the National Museum.

Soon afterwards, he was given prestige assignments including the overall architectural design for the Frederiksstaden district of Copenhagen 1749, planned around the strictly octagonal square containing the four Amalienborg Palaces and considered to be one of Europe's most important Rococo complexes. Adam Gottlob Moltke who, as Frederick V's overhofmarskal or lord chamberlain, was in charge of the project gave Eigtved a free hand, not only to design the principal buildings but also to provide the area with straight broad streets and the mansions which lined them.[32] Frederick V had wanted to emulate the grand building achievements of the French monarchs. Not surprisingly, therefore, the palace square is inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris from the same period.[33] Although Eigtved died before the work was completed, other architects including Lauritz de Thurah faithfully continued to execute his plans. Perhaps the finest outcomes are the Amalienborg Palace complex, Frederik's Church in its immediate vicinity and Frederiks Hospital.

Philip de Lange, although influenced by Eigtved, developed his own rather strict style during this period. His ornamental facade can be seen on the Kunstforeningen building (1750) on Gammel Strand in Copenhagen. The top storey with a gable was added later.[34] De Lange also designed the small but well proportioned Damsholte Church on Møn, the only Rococo village church in Denmark.[35]

Brandenburger, Ernst (1694), Clausholm Castle, Randers

Brandenburger, Ernst (1694), Clausholm Castle, Randers Christensen, Christen (1681), Nyhavn 9–15 - Copenhagen

Christensen, Christen (1681), Nyhavn 9–15 - Copenhagen Eigtved, Nicolai (1760), Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen

Eigtved, Nicolai (1760), Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen

Neoclassical

Neoclassicism which relied on inspiration from ancient Greece and Rome, was brought to Denmark by the French architect Nicolas-Henri Jardin. His countryman, the sculptor Jacques Saly, who was already well established in Denmark, persuaded Frederick V that Jardin could complete Frederik's Church after Eigtved's death. Although Jardin did not succeed in this, he was successful in designing several prestige Neoclassical buildings such as Bernstorff Palace (1759–65) in Gentofte and Marienlyst Palace near Helsingør.

One of Jardin's pupils, Caspar Frederik Harsdorff, turned out to be Denmark's most prominent 18th-century architect and is known as the Father of Danish Classicism. He undertook a considerable amount of redesign work, both for interiors and exteriors, including work on the Royal Theatre (1774) where he introduced a classical temple style with a wide entrance and large hall. He also carried out work on the Amalienborg complex including the colonnade, with its eight Ionic wooden columns, linking the crown prince's residence (Schacks Palæ) with the king's (Moltkes Palæ).[36][37]

Another remarkable example of neoclassicism is Liselund on the island of Møn in south-eastern Denmark. This rather small country home built in the French Neoclassical style in the 1790s is exceptional in that it has a thatched roof. Like the surrounding Romantic park, the house was the work of Andreas Kirkerup, one of the foremost landscape architects of the times. It was designed as a summer retreat for Antoine de la Calmette, the island's governor, and his wife, Lise.[38] The building is T-shaped with the main rooms on the ground floor, the first floor consisting of nine bedrooms. The interior was probably decorated by the leading decorator of the day, Joseph Christian Lillie.

19th century

Classicism

After Hardorff's death, the main proponent of Classicism was Christian Frederik Hansen who developed a more severe style with clean, simple forms and large, unbroken surfaces. From 1800, he was in charge of all major building projects in Copenhagen where he designed the Copenhagen City Hall & Courthouse (1805–15) on Nytorv. He was also responsible for rebuilding Church of Our Lady (Vor Frue Kirke) and designing the surrounding square (1811–29).

In 1800, Hansen was also charged with rebuilding Christiansborg Palace which had burnt down in 1794. Unfortunately, it burnt down once again in 1884. All that remains is the magnificent chapel which, with its Ionic columns, conveys a sense of antiquity.[39]

Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll is remembered above all for designing Thorvaldsens Museum. In 1822, as a young man, he had experienced Karl Friedrich Schinkel's classicism in Germany and France and had met the German-born architect and archaeologist Franz Gau who introduced him to the colourful architecture of antiquity. His uncle, Jonas Collin, who was an active art and culture official under Frederick VI, awakened the King's interest in a museum for Bertel Thorvaldsen, the Danish-Icelandic sculptor, and asked Bindesbøll to make some sketches for the building. As Bindensbøll's designs stood out from those of other architects, he was given a commission to transform the Royal Carriage Depot and Theatre Scenery Painting Building into a museum. Emulating the construction of the Erechtheion and the Parthenon as freestanding buildings released from the traditional urban plan of closed streets, he completed the work in 1848.[40] He also incorporated aspects of ancient Egyptian architecture into his design, though "the plan as a whole... is neither Egyptian nor Greek, but Bindesbøll's own."[41]

Historicism

With the arrival of Historicism in the second half of the century, special importance was attached to high standards of craftsmanship and proper use of materials. This can be seen in Copenhagen's University Library (1861) designed by Johan Daniel Herholdt and inspired by St Fermo's Church in Verona.

Vilhelm Dahlerup was one of the most productive 19th-century architects. Perhaps more than anyone else, he contributed to the way Copenhagen appears today.[42] His most important buildings include Copenhagen's Hotel D’Angleterre (1875) and the Danish National Gallery (1891). With the support of the Carlsberg company, he designed the Ny Carlsberg Glyptoteque (1897) and a number of lavishly decorated buildings at the Carlsberg Brewery site, now under redevelopment as a new district in Copenhagen.[43]

Ferdinand Meldahl, also a proponent of Historicism, completed the reconstruction of Frederiksborg Palace after the fire in 1859 and designed the Parliament Building in Reykjavík, Iceland, at that time a Danish colony. His greatest achievement was, however, the completion of Frederik's Church in Copenhagen. The site had become a ruin after work was stopped on Jardin's original design in 1770. Meldahl's plans differed significantly from Jardin's in that the lateral towers were eliminated, the dome was lower and the columns were reduced from six to four before the main entrance. Nevertheless, the overall height almost matched Jardin's, thanks to the lantern and the taller spire. The building, commonly known as the Marble Church, was completed in 1894, more than 150 years after Eigtved had drawn up his original plans.[44]

National Romanticism

Martin Nyrop was one of the main proponents of the National Romantic style. The main aim was to use distinctive Nordic motifs from the distant past, as is clearly demonstrated in Copenhagen City Hall which was completed in 1905. The City Hall is certainly Copenhagen's most monumental and most original building from the last quarter of the 19th century with its impressive facade, the golden statue of Absalon just above the balcony and its tall, slim clock tower. It was inspired by the Siena City Hall.[45]

Another participant in the National Romanticism movement was Hack Kampmann who designed the Aarhus Theatre in the Art Nouveau style at the very end of the century.

Urban development

The harbour town of Svendborg in the south east of Funen dates back to the 13th century. Real prosperity emerged in the 19th century when shipbuilding and trade became important drivers. The town subsequently underwent a period of renovation with new brick and stone buildings lining its narrow streets. The old town has now become an important tourist attraction.[46]

The fine architectural style of Skagen on the northern tip of Jutland is quite distinctive. From the 19th century on, the houses were whitewashed and had red-tiled roofs. Yellow and red tones dominated, backed by white chimneys and roof decorations. These traditions are not only to be found in the town's old districts but are maintained in the newer residential areas. Several of the town's more imposing buildings from the beginning of the 20th century were designed by the Ulrik Plesner, others were designed by well-known architects such as Thorvald Bindesbøll.[47]

Gottlieb Bindesbøll, Michael (1838–48), Thorvaldsens Museum

Gottlieb Bindesbøll, Michael (1838–48), Thorvaldsens Museum

.jpg) Kampmann, Hack (1898–1900), Aarhus Theatre

Kampmann, Hack (1898–1900), Aarhus Theatre Nyrop, Martin (1905), Copenhagen City Hall

Nyrop, Martin (1905), Copenhagen City Hall

20th century

Nordic Classicism

Neoclassicism or increasingly Nordic Classicism continued to thrive at the beginning of the century until about 1930 as can be seen in Kay Fisker's Hornbækhus apartment buildings (1923) and Hack Kampmann's police headquarters (1924). Its development was no isolated phenomenon, drawing on existing classical traditions in the Nordic countries, and from new ideas being pursued in German-speaking cultures. It can thus be characterised as a combination of direct and indirect influences from vernacular architecture (Nordic, Italian and German) and Neoclassicism.[48]

While the movement had its greatest level of success in Sweden, there were a number of other important Danish proponents including Ivar Bentsen, Kaare Klint, Arne Jacobsen, Carl Petersen and Steen Eiler Rasmussen. Bentsen, with the assistance of Thorkild Henningsen, designed Denmark's first terraced houses in the Bellahøj district of Copenhagen. Very appropriately Klint, working with Bentsen, adapted the design of Frederiks Hospital to serve as the Danish Museum of Art & Design. Carl Petersen's main achievement was the Faaborg Museum built for collections of art from Funen. Steen Rasmussen is remembered above all for his town planning activities and for his contributions to the Dansk Byplanlaboratorium (Danish town planning laboratory).[49][50]

Expressionism

Grundtvig's Church in Bispebjerg, Copenhagen, is named after the Danish philosopher and pastor Nikolai Grundtvig, remembered by most Danes for his resounding hymns, now an integral part of the national culture. As a result of its unusual appearance, it is Denmark's most famous expressionist church. Designed by Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint, it relied heavily on Scandinavian brick gothic traditions, especially Danish village churches with stepped gables. Jensen-Klint combined the modern geometric forms of Brick Expressionism with the classical vertical of Gothic architecture. Construction began in 1921 but was only completed by his son Kaare Klint in 1940 after Jensen-Klint's death. The most striking feature of the building is its west facade, reminiscent of a westwork or of the exterior of a church organ.[51]

Functionalism

_01.jpg)

Functionalism, which began in the 1930s, relied on rational architecture making use of bricks, concrete, iron and glass, preferably to meet social needs. Its main proponents in Denmark were Frits Schlegel, Mogens Lassen, Vilhelm Lauritzen and, especially Arne Jacobsen with his Bellavista developments north of Copenhagen. Another of Jacobsen's masterpieces was the Aarhus City Hall which he designed together with Erik Møller in 1937 and completed in 1948. The tower is 60 meters tall and the tower clock face has a diameter of 7 meters. The building is made of concrete plated with marble from Porsgrunn in Norway.[52][53]

A more traditional approach was taken by Kay Fisker who, together with C. F. Møller, designed buildings for Aarhus University from 1931 onwards.[54]

Modernism

After World War II, Functionalism drew on trends in American Modernism with its irregular ground plans, flat roofs, open plan interiors and glass facades. Good examples are Jørn Utzon's own family house (1952) on the outskirts of Hellebæk near Helsingør where good use is made of reasonably cheap materials for post-war housing;[55] and the Kingo Houses (1956–58) in Helsingør which consist of 63 L-shaped houses based upon the design of traditional Danish farmhouses. Another project, noted for the synthesis it creates between architecture and landscape, was the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (1958) in Humlebæk, designed by Jørgen Bo and Vilhelm Wohlert.

During this period, Arne Jacobsen became the country's leading Modernist with the design of the SAS Hotel in Copenhagen (1960). Rødovre Town Hall, completed in 1956, shows how well Jacobsen combined the use of different materials: sandstone, two types of glass, painted metalwork and stainless steel.[56]

Following in Jacobsen's footsteps, Denmark had some outstanding successes in 20th-century architecture. Most notably, Jørn Utzon's iconic Sydney Opera House earned him the distinction of becoming only the second person to have his work recognized as a World Heritage Site while still alive.[57] His Bagsværd Church (1968–76) in Copenhagen has been considered an outstanding example of critical regionalism, for the synthesis created between universal civilisation and regional culture.[58]

Winning the international competition for the Grande Arche at La Défense in Puteaux, near Paris, with a design based on simple geometrical forms brought Johann Otto von Spreckelsen international fame. Prolific Henning Larsen designed the Foreign Ministry building in Riyadh, as well as a variety of prestige buildings throughout Scandinavia, including the Copenhagen Opera House.[59]

From the success of the Strøget's transformation into a pedestrian zone in Copenhagen in the 1960s and his influential book Life Between Buildings, Jan Gehl earned an international reputation in urban design. He has advised on numerous city planning developments including those for Melbourne, London and New York.[60] His work has often drawn on Copenhagen and its bicycle culture, to improve the quality of public space in city centres.[61]

Jacobsen, Arne (1933–34), Bellavista (apartments)

Jacobsen, Arne (1933–34), Bellavista (apartments) Fisker, Kay (1931), Århus University

Fisker, Kay (1931), Århus University

Postmodernism

Postmodernism and postmodern architecture have also had its imprint on Danish architecture, with large and notable projects such as Høje-Taastrup train station from 1986 by Jacob Blegvad, the multi-purpose venue of Scala in central Copenhagen, just across from Tivoli Gardens, redeveloped in 1989 from a design by architect and professor Mogens Breyen, but torn down in 2012, or Scandinavian Center in Aarhus by Friis & Moltke from 1995.[62][63][64] Several housing projects in Denmark, especially larger social housing projects, from the 80s and early 90s was also inspired by the postmodern movement of the time. Notable examples include the relatively small apartment complex Det Blå Hjørne (The Blue Corner) in Christianshavn, by Tegnestuen Vandkunsten or the larger and much more recent Bispebjerg Bakke, in Bispebjerg from 2006, designed in collaboration with artist Bjørn Nørgaard.[65]

Det Blå Hjørne (1983), Christianshavn

Det Blå Hjørne (1983), Christianshavn The Scala Building (1989)

The Scala Building (1989).jpg) Tycho Brahe Planetarium (1989, Knud Munk)

Tycho Brahe Planetarium (1989, Knud Munk) Scandinavian Center (1995), Aarhus

Scandinavian Center (1995), Aarhus_01.jpg) Glass and steel arcade (Scandinavian Center)

Glass and steel arcade (Scandinavian Center).jpg) Bispebjerg Bakke (2006)

Bispebjerg Bakke (2006)

Contemporary period

Since the turn of the millennium, Danish architecture has flourished both at home and abroad. Two important areas of Greater Copenhagen have provided substantial opportunities for architectural developments on the domestic front while a number of firms have gained international recognition, winning important commissions abroad. For some, overseas assignments have become as important as those in Denmark itself.

Recent years have also seen the emergence of several new architectural firms operating both in Denmark and internationally.

Recent urban developments

Ørestad is a contemporary urban development to the south-east of the Copenhagen's city centre. Its origin is connected with the building of the Øresund Bridge linking Copenhagen to Malmö in Sweden, completed in 2000. After initial planning stages in the 1990s, the first office building was realised in 2001. Today the constantly expanding area has more than 3,000 apartments and 192,100 m² of office space.[66][67]

Copenhagen itself has also been undergoing significant transformations in recent years with the encouragement of various projects along the waterfront. Based on initial planning work in the 1980s, the area has already seen the appearance of several prestige buildings including the Black Diamond national library extension (1999), the Opera House (2000) and the Royal Danish Playhouse (2004).[68]

International presence

Henning Larsen Architects, well established in the Nordic countries, are now active outside Denmark, particularly in the Middle East. They have a number of projects in Saudi Arabia and Syria, including the Massar Discovery Centre in Damascus.[69] Another interesting project is a new building for Der Spiegel on the waterfront in Hamburg.[70]

3XN have designed the award-winning Muziekgebouw Concert Hall in Amsterdam and the new Museum of Liverpool. In 2007, they won a competition for the design of a new headquarters for Deutsche Bahn in Berlin ahead of firms such as Foster + Partners of the UK and Dominique Perrault of France.[71]

Schmidt Hammer Lassen have opened offices in London and Oslo. In addition to numerous projects in the Nordic countries, their international work includes Westminster College in London and a new library for the University of Aberdeen.[72]

Among the most notable international projects of C. F. Møller Architects are extensions to the Natural History[73] and the National Maritime museums in London (2009–11).[74] They were also successful in being commissioned to build the Akershus University Hospital in Oslo.[75]

Dissing+Weitling are widely recognized as bridge architects after completing some 220 such projects worldwide. These include the Great Belt Bridge between Sealand and Funen, the Queensferry Crossing in Scotland, the Nelson Mandela Bridge in South Africa and the Stonecutters Bridge in Hong Kong. The Great Belt suspension bridge, completed in 1998, is the world's third largest. With a length of 6,790 metres (22,277 ft) and a free span of 1,624 metres (5,328 ft), the vertical clearance for ships is 65 metres (213 ft).[76]

Lundgaard & Tranberg are the designers of the Royal Danish Playhouse and the Tietgenkollegiet student housing complex, both considered to be among Copenhagen's most successful new buildings in recent years.[77]

Emerging practices

Another trend in contemporary Danish architecture is the emergence of a new generation of successful young practices, inspired more by international trends than by the modernist tradition in Scandinavia. The generation is spearheaded by Bjarke Ingels whose firm BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) founded in 2006 has made an unusually rapid transition into a well-established firm.

From the beginning, BIG received international recognition for a number of projects, including Mountain Dwellings in Ørestad.[78][79] Ideologically and conceptually, the practice is more closely related to Dutch firms such as OMA – where Ingels worked from 1998 to 2001 – and MVRDV than to the work of Danish architects. BIG's major international breakthrough came in 2009 when the firm won six international competitions and gained several large commissions. These include an art museum on a cliffside overlooking Mexico City,[80] a canalside neighbourhood in Hamburg,[81] a new city hall for Tallinn, Estonia,[82] a new national library for Kazakhstan,[83] a low-energy highrise project in Shenzhen, China,[84] and a World Village for Women's Sports in Malmö.[85]

Four young practices, CEBRA, Cobe, Transform and Effekt, contributed to the project CO-EVOLUTION: Danish/Chinese Collaboration on Sustainable Urban Development in China, which was awarded the Golden Lion at the 2006 Venice Biennale of Architecture. The project was commissioned by the Danish Architecture Centre and curated by the Danish architect-urbanist Henrik Valeur and UiD.[86][87] All four practices later went on to win high-profile competitions in Denmark and abroad. Effekt has won the competition for a new building for the Estonian Art Academy in Tallinn,[88] Transform has a project on the City Hall Square in Copenhagen[89] and Cobe has won first prize in a competition for Scandinavia's largest sustainable district in Nordhavnen, Copenhagen.[90]

Other notable emerging Danish architectural practices include Aart,[91] Dorthe Mandrup Architects and NORD Architects.[92]

Lassen, Schmidt Hammer (1999), The Black Diamond (National library)

Lassen, Schmidt Hammer (1999), The Black Diamond (National library) Larsen, Henning (2000–2004), Copenhagen Opera House

Larsen, Henning (2000–2004), Copenhagen Opera House Ingels, Bjarke (2008), Mountain Dwellings (Residential), Ørestad

Ingels, Bjarke (2008), Mountain Dwellings (Residential), Ørestad Tietgenkollegiet (Student housing), Ørestad: Lundgaard & Tranberg, 2005–2006

Tietgenkollegiet (Student housing), Ørestad: Lundgaard & Tranberg, 2005–2006 DOKK1 and Havnepladsen (Cultural center and public squares), Aarhus: Schmidt hammer lassen, 2011–2017

DOKK1 and Havnepladsen (Cultural center and public squares), Aarhus: Schmidt hammer lassen, 2011–2017

References

- "Viking Houses architecture: inside layout", Viking Denmark, retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Vikingeborgen Fyrkat (in Danish), DK: Sydhimmer landsmuseum, archived from the original on 4 August 2009, retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Introduction to the Restoration of Danish Wall Paintings, DK: The National Museum, archived from the original on 24 November 2009, retrieved 11 November 2009.

- "St Bendt's Ringsted", Visit Vordingborg, DK, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 11 November 2009.

- "Summary", Vor Frue Sogn, DK: Folke Kirken, archived from the original on 4 August 2009, retrieved 15 December 2009.

- "Østerlars Kirke", Home of our fathers, archived from the original on 3 January 2013, retrieved 15 November 2009.

- "Lund Cathedral", The Green Guide, UK: Via Michelin, retrieved 15 January 2009.

- Architecture, DK: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, archived from the original on 13 May 2009, retrieved 11 November 2009

- "Churches and cathedrals", Culture, Visit Denmark, archived from the original on 17 July 2011, retrieved 5 December 2009.

- "Glimmingehus", Skånska slott och herrestäten (in Swedish), SE: Algo net, retrieved 8 December 2009.

- Anne Hvides Gård i Fruestræde (in Danish), DK: Fynhistorie, retrieved 14 November 2009.

- A walk through the centuries, SE: Ystads kommun, archived from the original on 25 July 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Collections, DK: DenGamleBy, archived from the original on 19 May 2010, retrieved 22 November 2009

- "Kronborg", World Heritage Site, UNESCO, retrieved 11 November 2009.

- The History of Rosenborg Castle, DK: Rosenborg slot, archived from the original on 18 March 2007, retrieved 7 December 2009.

- "Copenhagen Remembers the Renaissance", Copenhagen specialities, Visit Copenhagen, archived from the original on 25 October 2008, retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Skovgaard, Joakim A (1973), A king's architecture: Christian IV and his buildings, London, ISBN 0-238-78979-9.

- Holbæks historie (in Danish), DK: Bibliotek Holbæk, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Kølstrup Vicarage (JPEG), DK: Wikipædia.

- "Trinitatis Kirke og Rundetårn". DK: Kloakviden. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Round Tower, Copenhagen, DK: Copenhagenet, retrieved 9 December 2009.

- "Nysø", The Astoft Collection of Buildings of Denmark, UK, archived from the original on 20 August 2010, retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Historie", Vor Frelsers Kirke (in Danish), DK, archived from the original on 26 August 2010, retrieved 12 November 2009.

- Renouf, Norman (2003), Copenhagen & the best of Denmark alive!, Edison, NJ: Hunter, bA3Y5761, 257 pp.

- "Historien om Nyhavn 9", Rikkitikki (in Danish), DK, retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Clausholm Slotskapel (in Danish), DK: Musik historisk museum, archived from the original on 28 September 2007, retrieved 12 November 2009.

- Christiansborgs Ridebane (in Danish), DK: Dansk Arkitektur Center, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Fredensborg Slot (in Danish), DK: Dansk Arkitektur Center, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "Slotshave restaureres for 44 millioner". DK: Jyllands Posten. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Kancellibygningen (Den røde bygning), Slotsholmsgade 4", København. Kulturhistorisk opslagsbog (in Danish), DK: Københavns historie, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Ledreborg slot [Ledreborg Palace], DK, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 7 December 2009.

- Frederiksstaden (in Danish), DK: Dansk Architectur Center, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 13 November 2009.

- TRH The Crown Prince and Crown Princess, DK, archived from the original on 20 February 2009, retrieved 22 November 2009

- Gammel Strand (in Danish), København, DK: ByMuseet, retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Damsholte Kirke (in Danish), DK, 7 December 2009.

- Klassicisme (in Danish), DK: Dansk Architectur Center, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 13 November 2009.

- "Amalienborg Palace", Copenhagenet, DK, archived from the original on 14 December 2009, retrieved 7 December 2009.

- Eskling, Ole; Büchert, Erik, Liselund park and manor house, Møns, DK: Turistbureau.

- "Christiansborg Palace Chapel", Guide to the Danish Golden Age, DK: Guld alder, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 7 December 2009.

- Lange, Bente; Lindhe, Jens (2002), Thorvaldsen's Museum: Architecture, Colours, Light, Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press.

- Laurin, Carl; Hannover, Emil; Thiis, Jens (1968), Scandinavian Art (hardback), New York: Benjamin Blom, p. 425.

- "Vilhelm Dahlerup". Det moderne gennembrud. DK: Golden Days in Copenhagen. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- "Carlsberg design develops in Copenhagen". World Architecture News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- Marble Church, Copenhagen, DK: Copenhagenet, archived from the original on 20 August 2009, retrieved 7 December 2009.

- "City Hall Tower Clock", Waymarks, Waymarking, retrieved 13 November 2009.

- "Svendborgs historie", Fyn historie (in Danish), DK, retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "Skagen's history", Skagen tourist, DK: Visit Denmark, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "First half of 20th century", Danish Architecture, DK: About Denmark, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 28 December 2009.

- Angeletti, Angelo; Remiddi, Gaia (1998). Alvar Aalto e il Classicismo Nordico (in Italian and English). Rome: F.lli Palombi. ISBN 88-7621-666-9.

- "Steen Rasmussen", EES (PDF) (CV), LANL, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010, retrieved 28 December 2009.

- Grundtvigs Kirke, DK, archived from the original on 1 February 2010, retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Functionalism and Tradition", Danish architecture: an overview, Visit Denmark, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 28 December 2009.

- The City Council Hall, Århus Kommune, 28 December 2009.

- "Danish Functionalism", World Architecture Images, Essential architecture, retrieved 28 December 2009.

- "Second half of the 20th Century", Danish architecture: an overview, DK: Visit Denmark, archived from the original on 19 July 2011, retrieved 15 January 2010.

- "Rødovre Kommune – Arne Jacobsen", Kulturarv og kulturfremme, DK: RK, archived from the original on 30 November 2009, retrieved 15 December 2009.

- Kathy Marks (27 June 2007). "World Heritage honour for 'daring' Sydney Opera House". The Independent. London: Independent News & Media. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Frampton, Kenneth, Scott Paterson: Critical Analysis of "Towards a Critical Regionalism", Earthlink, retrieved 13 December 2009.

- "Henning Larsen", Kunst og kultur: Arkitektur Danmark (in Danish), DK: Den Store Danske, retrieved 5 November 2009.

- "Jan Gehl" (PDF) (biography). JGA. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Gehl on Wheels". New York News & Features. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- "Høje taastrup Station". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Farvel til et festhus

- "Scandinavian Center". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Bispebjerg Bakke

- "Ørestad", Fakta (in Danish), DK, archived from the original on 14 February 2010, retrieved 8 December 2009.

- Ørestaden – et centrum i periferien (PDF) (in Danish), DK: Uni geo, retrieved 8 December 2009.

- "Waterfront", Town areas, Copenhagen: Visit Copenhagen, archived from the original on 14 December 2010, retrieved 8 December 2009.

- "Damascus flowers educational future". World Architecture News. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Architectural Design for Spiegel Group". Hamburg. HafenCity. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- "Competition win for 3XN". World Architecture News. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Library turns new leaf". World Architecture News. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- Morgan, James (2 September 2008). "Museum 'cocoon' prepares to open". BBC. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- "First sketches of Maritime Museum revealed". World Architecture News. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- "Top healthcare award for CF Møller". World Architecture News. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- "Fakta og historie". DK: A/S Storebælt. Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- "Her er opturens ti bedste byggerier". Børsen. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- "Urban Land Institute presents Award of Excellence to the Mountain". +MOOD. 2009. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- "MIPIM Awards Winners 2009 Announced". Bustler. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- New Tamayo Museum by Rojkind Arquitectos and BIG, Dezeen, retrieved 6 December 2009

- "Kaufhauskanal Metrozone / BIG + Topotek1". ARCHdaily. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Tallinn City Hall by Bjarke Ingels Group". Dezeen. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Astana National Library by BIG". Dezeen. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Shenzhen International Energy Mansion by BIG". Dezeen. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Taking on the women of the world". Dezeen. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "About the exhibition". Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Co-Evolution site". Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Young Danes seal Art Plaza bid". World Architecture News. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Københavns Rådhusplads får ansigtsløftning" (in Danish). DK: Berlingske. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "Vinder 1. præmie i international idékonkurrence om Nordhavnen i København" (in Danish). DK: Rambøll. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Årt, DK, archived from the original on 28 January 2010.

- Design Nord, DK, archived from the original on 30 September 2009, retrieved 16 December 2009.

Further reading

- A nation of architecture (PDF), DK: Ministry of Culture, 2007, 52 pp.

- Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Kim; Keiding, Martin; Amundsen, Marianne; Smidt, Claus M (2007), Danish architecture since 1754, Danish Architectural Press, 400 pp.

- Faber, Tobias (1978), A history of Danish architecture, Copenhagen: Det Danske Selskab, 316 pp.

- Gehl, Jan (c. 1987), Life between buildings: using public space, New York, Wokingham: Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0-442-23011-7, 202 pp.

- Lind, Olaf (2007), Architecture guide: Danish islands, Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press, 336 pp.

- Sestoft, Jørgen; Hegner, Christiansen Jørgen (1995), Guide to Danish architecture, Arkitektens Forlag, 2 vols, 272 pp.

- Ørum-Nielsen, Jørn (1966), Dwelling, Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press, 261 pp.

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: DK. Volvemos a Dinamarca, 2010, Barcelona, Grupo PAB. Departamento de Proyectos Arquitectónicos, ETSAB, UPC, 100 pages. ISBN 978-84-608-1059-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Denmark. |

- "Architecture in Denmark", The Astoft Collection of Buildings, UK, archived from the original on 16 May 2008, providing details of some 70 architecturally interesting buildings, mainly in Copenhagen, Sealand and Funen.

- Danmarks Kirker [Churches in Denmark] (in Danish), DK: The National Museum, the major basic reference series about Danish churches and their murals, furnishings and monuments.

- Copenhagen X, DK, archived from the original (official website) on 28 November 2009, retrieved 9 December 2009 on modern architecture and urban development in Copenhagen.