Megaron

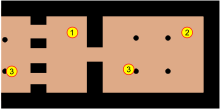

The megaron (/ˈmɛɡəˌrɒn/; Ancient Greek: μέγαρον, [mégaron]), plural megara /ˈmɛɡərə/, was the great hall in ancient Greek palace complexes. It was a rectangular hall, surrounded by four columns, that was fronted by an open, two-columned portico, and had a central, open hearth that vented though an oculus in the roof. It is believed that the ruler of the area, called an anax, had his throne placed in the room containing the hearth. Because of this, the main room is sometimes referred to as the "throne room".[1] Similar architecture is found in the Ancient Near East, though the presence of the open portico, generally supported by columns, is particular to the Aegean.[2] Megara are sometimes referred to as 'long-rooms', as defined by their rectangular (non-square) shape and the position of their entrances, which are always along the shorter wall so that the depth of the space is larger than the width.[3] There were often many rooms around the central megaron, such as archive rooms, offices, oil-press rooms, workshops, potteries, shrines, corridors, armories, and storerooms for such goods as wine, oil and wheat.[4]

Structure

The structure of the megaron foreshadowed an image for the eventual layout of Greek temples. This includes a columned entrance, a pronaos, and a central naos (cella). An early megaron has a pitched roof, and there were other roof types as well such as the flat roof and barrel roof.[3] These are always destroyed in the remnants of the early megaron, so the definite roof type is not known (see List of ancient Greek and Roman roofs for examples). In the history of architecture, the megaron is considered to be the earliest architectural act.

The floor was of patterned concrete, covered in carpet.[5] On the walls there were frescoes, often of Phoenician style.[6] Originally it was very colorful, the insides made of fired brick and a wooden roof supported on beams. The rooftop was tiled with ceramic and terra cotta tiles.[7] There were wood ornamented metal doors often two leaved, and foot-baths were also used in the megaron.[8] The proportions of a larger length than width is a similar structure to early Doric temples.[9]

Purpose

The megaron's functions were many, including feasts and worship. It was used for royal functions and court meetings as well.[2] Its religious functions included the practice of animal sacrifices, often to Chthonic deities.

Examples

A famous megaron is in the large reception hall of the king in the palace of Tiryns, the main room of which had a raised throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four Minoan-style wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. This was from a Cretan influence,[10] and evolved into the palace type from Minoan architecture. After that the Mycenaeans took over this design, making it characteristically Greek. Frescoes from Pylos show figures eating and drinking, which were important activities in Greek culture.[11] Bulls were also a theme in many Greek frescoes.[12] Other famous central megaron units are at Tiryns, Thebes, Mycenae, and Pylos. The decoration unifies each megaron suite decoratively. This also distinguishes famous megara, making them unique. Different Greek cultures had their own unique megara; for example, the people of the Mainland tended to separate their central megaron from the other rooms whereas the Cretans did not do this.[13]

References

- T., Neer, Richard (2012). Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500–c. 150 BCE. New York. ISBN 978-0500288771. OCLC 745332893.

- "Megaron". Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- Muller, Valentine (Oct–Dec 1944). "Development of the "Megaron" in Prehistoric Greece". Archaeological Institute of America. 48 (4): 342–348. JSTOR 499900.

- Pentreath, Guy. "A Greek Architecture Primer". Fodors LLC. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- Diehl, Charles (1893). Excursions in Greece: Recently explored sites of Classical interest. London: H. Grevel and Co. pp. 38–436 [53].

- Rider, Bertha C. (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to Hellenistic Age. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 60, 94–266.

- Rider, Bertha C. (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to Hellenistic Age. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–266 [180].

- Rider, Bertha C. (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to Hellenistic Age. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–266 [182].

- Rider, Bertha C. (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to the Hellenistic age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–266 [140].

- Muller, Valentin (Oct–Dec 1944). "Development of the "Megaron" in Prehistoric Greece". American Journal of Archaeology. 48 (4): 342–348 [347]. doi:10.2307/499900. JSTOR 499900.

- Wright, J.C. (2004). "A survey of evidence for feasting in Mycenaean society". Hesperia. 73 (2): 133–178 [161]. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.675.9036. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.133. ProQuest 216525567.

- Wright, J.C. (2004). "A survey of evidence for feasting in Mycenaean society". Hesperia. 73 (2): 133–178 [167]. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.675.9036. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.133. ProQuest 216525567.

- Rider, Bertha C. (1916). The Greek House: Its History and Development from the Neolithic Period to the Hellenistic age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–266 [127].

Further reading

- The megaron of Odysseus is well described in the Odyssey.

- Biers, William R. 1987. The Archaeology of Greece: An Introduction. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press)

- Klein, Christopher P. (Editor in Chief) Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Tenth edition. Harcourt Brace (1996). ISBN 0-15-501141-3

- Vermeule, Emily, 1972. Greece in the Bronze Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).