Helsinki Metro

The Helsinki Metro (Finnish: Helsingin metro, Swedish: Helsingfors metro) is a rapid transit system serving Greater Helsinki, Finland. It is the world's northernmost metro system. The Helsinki Metro was opened to the general public on 2 August 1982[4] after 27 years of planning. It is operated by Helsinki City Transport for HSL and carries 63 million passengers per year.[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

M300 train | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

M100, the oldest class still in use, en route to Vuosaari | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native name | Helsingin metro Helsingfors metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Greater Helsinki, Finland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of lines | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 25[1] 5 under construction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 304,000 (2017)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual ridership | 62,884,000 (2015)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | HKL Metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Began operation | 2 August 1982[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Helsinki City Transport | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System length | 35 km (21.7 mi)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,524 mm (5 ft) Broad gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 750 V DC[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The metro system consists of 2 lines, which serve a total of 25 stations. It has a total length of 35 kilometres (22 mi).[8] The metro serves as the predominant rail link between the suburbs of East Helsinki and the western suburbs in the city of Espoo and downtown Helsinki.

The line passes under the Helsinki Central Station allowing passengers to transfer to and from the Helsinki commuter rail network, including trains on the Ring Rail Line to Helsinki Airport.

History

1955–67: Light rail plan

The initial motion for building a metropolitan railway system in Helsinki was made in September 1955, though during the five decades beforehand, the idea of a tunneled urban railway for Helsinki had surfaced several times. A suburban traffic committee (esikaupunkiliikennekomitea) was formed under the leadership of Reino Castrén, and in late 1955, the committee set to work on the issue of whether or not there was truly a need for a tunneled public transport system in Helsinki. After nearly four years of work, the committee presented its findings to the city council. The findings of the committee were clear: Helsinki needed a metro system built on separate right-of-way. This was the first time the term "metro" was used to describe the planned system. At the time the committee did not yet elaborate on what kind of vehicles should be used on the metro: trams, heavier rail vehicles, buses or trolleybuses were all alternatives. The city council's reaction to the committee's presentation was largely apathetic, with several council members stating to the press that they did not understand anything about Castrén's presentation.[9]

Despite the lacklustre reception, Castrén's committee was asked to continue its work, now as the metro committee,[10] although very little funding was provided. In spring 1963 the committee presented its proposal for the Helsinki Metro system. On a technical level this proposal was very different from the system that was finally realised. In the 1963 proposal the metro was planned as a light rail system, running in tunnels a maximum of 14 metres below the surface (compared to 30 metres in the finalized system), and with stations placed at shorter intervals (for instance, the committee's presentation shows ten stations between Sörnäinen and Ruoholahti, compared to the six in the realized system).[11] The Castrén Committee proposed for the system to be built in five phases, with the first complete by 1969 and the final by 2000, by which time the system would have a total length of 86.5 kilometres (53.7 mi) with 108 stations.[10][11] This was rejected after lengthy discussions as too extensive. In 1964 the city commissioned experts from Hamburg, Stockholm and Copenhagen to evaluate the metro proposal. Their opinions were unanimous: a metro was needed and the first sections should be built by 1970.[12]

Although no official decision to build a system along the lines proposed by Castrén was ever made, several provisions for a light rail metro system were made during the 1950s–1960s, including separate lanes on the Kulosaari and Naurissaari bridges,[10] and space for a metro station in the 1964 extension of Munkkivuori shopping center.[11] The RM 1, HM V and RM 3 trams built for the Helsinki tram system in the late 1950s were also equipped to be usable on the possible light rail metro lines.[13]

1967–69: Heavy rail plan

In late 1967 Reino Castrén departed Helsinki for Calcutta, where he had been invited as an expert in public transport. Prior to his departure Castrén indicated he planned to return to Helsinki in six months and continue his work as leader of the metro committee. For the duration of Castrén absence Unto Valtanen was appointed as the leader of the committee. However, by the time Castrén returned, Valtanen's position had been made permanent. Following his appointment Valtanen informed the other members of the committee that the plans made under Castrén leadership were outdated, and now the metro would be planned as a heavy rail system in deep tunnels mined into bedrock.[11] Following two more years of planning, the Valtanen-led committee's proposal for an initial metro line from Kamppi to Puotila in the east of the city was approved after hours of debate in the city council on the early morning hours of 8 May 1969.[14] The initial section was to be opened for service in 1977.

1969–82: Construction

Construction of a 2.8-kilometre (1.7 mi) testing track from the depot in Roihupelto to Herttoniemi was begun in 1969 and finished in 1971.[15] The first prototype train, units M1 and M2, arrived from the Valmet factory in Tampere on 10 November 1971, with further four units (M3–M6) arriving the following year.[16] Car M1 burned in the metro depot in 1973.[17]

Excavating the metro tunnels under central Helsinki had begun in June 1971. Most of the tunneling work had been completed by 1976, excluding the Kluuvi bruise (Finnish: Kluuvin ruhje), a wedge of clay and pieces of rock in the bedrock, discovered during the excavation process. To build a tunnel through the bruise an unusual solution was developed: the bruise was turned into a giant freezer, with pipes filled with Freon 22 pushed through the clay. The frozen clay was then carefully blasted away, with cast iron tubes installed to create a durable tunnel.[18] Construction of the first stations, Kulosaari and Hakaniemi begun in 1974. The Kulosaari station was the first to be completed, in 1976, but construction of the other stations took longer.[19] As the case with many underground structures in Helsinki, the underground metro stations were designed to also serve as bomb shelters.[20]

In summer 1976 Teuvo Aura, the city director of Helsinki, signed an agreement with Valmet and Strömberg to purchase the trains required for the metro from them. In doing so Aura bypassed the city council completely, reportedly because he feared the council would decide to buy the rolling stock from manufacturers in the Soviet Union instead.[21] By this time the direct current–based technology of the M1 series trains had become outdated. In 1977 prototypes for the M100 train series (referred to as "nokkajuna", English: "beak train", to differentiate from the M1 prototypes) were delivered. In these units the direct current from the power rail was converted to alternating current powering induction motors. The M100 trains were the first metro trains in the world to be equipped with such technology.[22]

Aura's bypassing the city council in acquiring the rolling stock was not the only questionable part of the construction process of the Metro. On 3 June 1982, two days after the Metro had been opened for provisional traffic, Unto Valtanen came under investigation for taking bribes. Subsequently, several members of the metro committee and Helsinki municipal executive committee in addition to Valtanen were charged with taking bribes. In the end it was found that charges against all the accused except Valtanen had expired. Valtanen was convicted for having taken bribes from Siemens.[21]

1982 onwards: In service

On 1 June 1982, the test drives were opened to the general public. Trains ran with passengers during the morning and afternoon rush hours between Itäkeskus and Hakaniemi (the Sörnäinen station was not yet opened at this time). On 1 July the provisional service was extended to Rautatientori.[15][23] President of the Republic of Finland Mauno Koivisto officially opened the Metro for traffic on 2 August 1982 – 27 years after the initial motion to the city assembly had been made.[23]

The Metro did not immediately win the approval from inhabitants of eastern Helsinki, whose direct bus links to the city centre had now been turned into feeder lines for the Metro. Within six months of the Metro's official opening, a petition signed by 11,000 people demanded the restoration of direct bus links. Subsequently, the timetables of the feeder services were adjusted and opposition to the Metro mostly died down.[24]

On 1 March 1983 the Metro was extended in the west to Kamppi. The Sörnäinen station, between Hakaniemi and Kulosaari, was opened on 1 September 1984.[15]

The Metro was extended eastwards in the late 1980s, with the Kontula and Myllypuro stations opened in 1986, and the Mellunmäki station following in 1989.[24] The construction of a westwards expansion begun in 1987 with tunneling works from Kamppi towards Ruoholahti. The Ruoholahti metro station was opened on 16 August 1993.

Another new station followed: the Kaisaniemi station, between Rautatientori and Hakaniemi, was opened on 1 March 1995. It had in fact been decided on already in 1971, and the station cavern had been carved out of the rock during the original tunneling works, but a lack of funds had pushed back the station's completion.

On 31 August 1998, after four years of construction, the final section of the original plan was completed, with the opening of a three-station fork from Itäkeskus to Vuosaari.[25]

The second generation of Metro trains to be used in passenger service (the M200 class) were delivered in 2000 and 2001 by Bombardier.[26] These trains are based on Deutsche Bahn's Class 481 EMUs used on the Berlin S-Bahn network.[27]

On 25 September 2006, the city council of Espoo approved, after decades of debate, planning, and controversy, the construction of a western extension of the Metro. Under the plan, Metro trains will run to Matinkylä by the end of 2017.[28][29] (See section The future below.)

On 1 January 2007, Kalasatama station, between the Sörnäinen and Kulosaari stations, was opened. It serves the new "Sörnäistenranta-Hermanninranta" (Eastern Harbour) area, a former port facility that will be redeveloped as its functions are moved to the new Port of Vuosaari in the east of the city.

After 8 November 2009, the Rautatientori station, under the Central Railway Station, was closed to the public because a burst water pipe flooded it.[30] After renovations, the station reopened for public use on 15 February 2010.[31] The lifts were still under renovation, but they also reopened for service on 21 June 2010.[32] On 23rd August 2019 heavy rain caused again water damage on the Rautatientori station[33]. The station was opened in a few days but the lifts remained closed until 17th March 2020[34].

2006 onwards: The western extension

The construction of the Western extension from Ruoholahti to Matinkylä in Espoo was approved by the Espoo city council in 2006. Construction began in 2009[35] and the extension was opened in 18 November 2017. This first stage of the extension was 14 km (8.7 mi) long, with eight new stations, two in Helsinki and six in Espoo[36][37] and was built entirely in a tunnel excavated in bedrock.

After first stage of the Western extension opened the bus lines in Southern Espoo were reconfigured as feeder lines to either Matinkylä or Tapiola metro stations instead of terminating at Kamppi in the centre of Helsinki.

Before the extension of the metro, trains could be a maximum length of three units (each unit being two cars) but the new stations west of Ruoholahti were built shorter than the existing stations because it was originally planned to introduce driverless operation. The driverless project was cancelled in 2015 but the shorter new stations mean that the maximum train length is reduced to two units which is actually shorter than before. To increase capacity the automatic train protection system theoretically permits headway as short as 90 seconds, if needed in the future.[38]

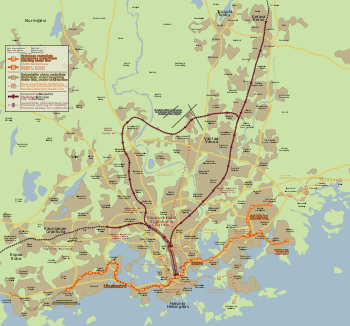

Network

The Helsinki metro system consists of 25 stations. The stations are located along a Y shape, where the main part runs from the Matinkylä through the center of the city towards the eastern suburbs. The line forks at the Itäkeskus metro station. 16 of the network's stations are located below ground; all eight of those stations located above ground are in Helsinki.

Trains are generally operated as Matinkylä–Vuosaari or Tapiola–Mellunmäki with some services running Matinkylä–Mellunmäki depending on the time of day. There is a rush-hour interval of 2 1⁄2 minutes in the central section of Tapiola–Itäkeskus. The metro trains stop at every station, and the names of the stations are announced in both Finnish and Swedish (with the exceptions of Central Railway Station, University of Helsinki and Aalto University, which are also announced in English).

The metro is designed as a core transport facility, which means that extensive feeder bus transport links are provided between the stations and the surrounding districts. Taking a feeder bus to the metro is often the only option to get to the city centre from some districts. For example, since the construction of the metro, all daytime bus routes from the islands of Laajasalo terminate at the Herttoniemi metro station with no through routes from Laajasalo to the centre of Helsinki.

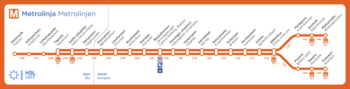

Lines

The Helsinki Metro is operated as three lines notionally called M1, M2 and M2M although these designations only appear on some trains and not at all on platform displays.[39]

| Line | Stretch | Stations | Travel time |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | |||

| M2 | |||

| M2M |

List of stations

- Matinkylä (Mattby), below surface

- Niittykumpu (Ängskulla), below surface

- Urheilupuisto (Idrottsparken), below surface

- Tapiola (Hagalund), below surface

- Aalto University (Aalto-yliopisto / Aalto-universitetet), below surface

- Keilaniemi (Kägeludden), below surface

- Koivusaari (Björkholmen), below surface

- Lauttasaari (Drumsö), below surface

- Ruoholahti (Gräsviken), below surface

- Kamppi (Kampen), below surface

- Central Railway Station (Rautatientori / Järnvägstorget), below surface

- University of Helsinki (Helsingin yliopisto / Helsingfors universitet), formerly Kaisaniemi (Kajsaniemi), below surface

- Hakaniemi (Hagnäs), below surface

- Sörnäinen (Sörnäs), below surface

- Kalasatama (Fiskehamnen), above surface

- Kulosaari (Brändö), above surface

- Herttoniemi (Hertonäs), below surface

- Siilitie (Igelkottsvägen), above surface

- Itäkeskus (Östra centrum), below surface

- Myllypuro (Kvarnbäcken), above surface

- Kontula (Gårdsbacka), above surface

- Mellunmäki (Mellungsbacka), above surface

- Puotila (Botby gård), below surface

- Rastila (Rastböle), above surface

- Vuosaari (Nordsjö), above surface

Accessibility

Some stations are located above ground level, making the metro system more friendly to passengers with mobility problems. Most sub-surface stations have no stairs, and one can access them from the street level via escalators or lifts.

The trains themselves have no steps, and the platforms are always at the same level as the train floor.

Ticketing

The ticketing scheme on the Metro is consistent with other forms of transport inside the city of Helsinki, managed by the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority (HSL) agency. The HSL travel card (matkakortti) is the most commonly used ticket, which can be paid either per journey or for a period of two weeks to one year. The metro stations between Koivusaari and Kulosaari lie within the A-zone while rest lie within the B-zone so an AB-ticket covers the whole Metro. Single tickets can be bought from ticket machines at the stations or via mobile app.[40] A single ticket can be used to change for any other form of transport inside Helsinki city with the validity time based on the number of zones purchased. There are no gates to the platforms; a proof-of-payment system is used instead.

Safety

Passenger safety instructions are inside train carriages above the doors and stations at ticket hall and platforms. These instructions direct passengers to use emergency phones and also include an emergency phone number to traffic center. There is emergency-stop handles at platforms, which are used to stop the train either arriving or departing in cases such as person trapped between doors, or person fallen onto track. There are emergency brake handles inside the carriage next to the door and at both ends of carriage.

Especially for people with visual impairments, all platforms have a yellow line marking the safe area on platform. Additionally, there are fire extinguishers on trains and in stations.

Helsinki metro has been nominated as the safest metro in the world

Rolling stock

The trains on the Helsinki Metro are technologically quite similar to trains on the VR commuter rail network, which serves the northern and western suburbs of Helsinki. The track gauge is 1,524 mm (5 ft) (broad gauge), as in all Finnish railway traffic. The electricity used by the metro trains is a 750-volt direct current drawn from an electricity track (also known as third rail) on the side of the metro tracks. Trains can be formed into 4- or 6-car sets (from 2-car twin sets).

There are three different types of train in service on the system as of 2016. The first trains adopted on the system consisted of the M100 series that was built by Strömberg in the late 1970s to the early 1980s. The newer M200 series was built by Bombardier and has been in service since 2000; each set is composed of two cars connected by an open gangway. The latest version, the M300 series, entered service in 2016 and will be completed by CAF before 2020; unlike the first two series, the M300 trains operate as 4-car sets with open gangways and were designed to run without drivers. Even though the system was built in the 1970s and 1980s, it is still modern compared to most other metros in the world.

The normal speed of the metro trains is 70 kilometres per hour (43 mph) inside the tunnels and 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph) on the open portion of the network. The points have a maximum structural speed of either 35 kilometres per hour (22 mph) or 60 kilometres per hour (37 mph). Technically the M200 and M100 series would be capable of doing 120 km/h (75 mph) and 100 km/h (62 mph), respectively, but they have been restricted to 80 km/h (50 mph).

The depot

The maintenance and storage depot for the metro system is at Roihupelto, between the stations of Siilitie and Itäkeskus. The depot is connected to the metro line from both the east and western directions, with a third platform at Itäkeskus used for alighting passengers before returning to the depot. Both heated and unheated undercover storage areas are provided so that trains are ready for use without a lengthy heating period.

Behind the Roihupelto depot is the metro test track, allowing testing at speeds of up to 100 km/h; the far end of this test-track was connected via a non-electrified 5 km long railway route to the VR main line at Oulunkylä railway station. Both the metro and mainline share a 1,524 mm (5 ft) track gauge. The old access line was mostly along the first half of the old Herttoniemi Harbour railway. Through the area of Viikki, this single line had street running. The Jokeri bus-line makes use of the depot line's railway bridges to cross Vantaa river and Finnish national road 4.

In 2012 the old depot link was closed and partially removed when a new 2 km metro link line was built from the then present end at Vuosaari metro station, to the VR harbour railway in the new Vuosaari harbour. The old link line will be rebuilt for the light rail-based Jokeri line upgrade, scheduled for 2016 onwards.

Future

The second phase of the Western extension

The decision to fund the construction of the second stage, from Matinkylä to Kivenlahti, was taken by the Espoo city council and the state of Finland in 2014. Construction began in late 2014. This stage of extension is 7 km (4.3 mi) long and includes five new stations and a new depot in Sammalvuori. All of the track, including the depot, will be built in tunnels. The line is projected to open for passenger traffic in 2022.[41]

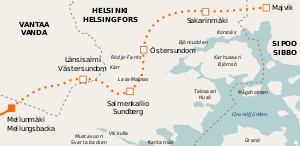

Eastern extension

In 2018, a new zoning plan for the Östersundom area east of Helsinki, was confirmed. New homes are due to be built on the condition that the metro is extended eastwards to serve this area.[42]

Other

A second Metro line from Laajasalo via Kamppi to Pasila north of the city centre, and possibly onwards to Helsinki-Vantaa Airport, is also in the planning stages. This is being taken into consideration in city plans and has been discussed by the city assembly, but does not look likely to be seriously planned before the mid-2030s at the earliest. To prepare for this eventuality, a platform level for a crossing line was already excavated during the original construction of the Kamppi station.

The Ring Rail Line, which connects the airport to the rail network, began service in 2015. The current plans commissioned by the city recommend the extension of the tram network, instead of the metro, to Laajasalo. Thus construction of a second metro line along the Laajasalo–Kamppi–Airport route appears unlikely.

On 17 May 2006 the Helsinki city council decided that the current, manually driven metro trains would be replaced by automatic ones, operated without drivers.[43] This project was cancelled in 2015 but the western extension was planned with this driverless operation in mind and the stations were built shorter than the existing ones which meant that the maximum train length for the whole system had to be reduced in 2017 when the western extension opened.

The system is planned to be automated as the old m100 trains come to the end of their lifespan.

There is a plan to extend the Vuosaari section of the line to the new Vuosaari harbour (see section The depot above).

A new station is being planned in Roihupelto, between Siilitie and Itäkeskus, to serve a possible future suburb.[44]

Unused stations

In addition to the metro stations already in operation, forward-looking design has led to extra facilities being constructed in case they are needed in the future.

- Kamppi

- The current metro station lies in an east-west direction. A second metro station was excavated at the same time of construction in 1981. This station is perpendicular (north-south) to the first one and has platforms 100 m in length, slightly shorter than those above.[45] Tunnels designed to eventually connect the two sets of lines curve off from the west-end of Kamppi. See also: Helsingin Sanomat published side elevation plan and photograph of second level.

- Hakaniemi

- Two station boxes were constructed in Hakaniemi. Intended for future expansion, the second is now unused.[46] The unused area was subsequently designated for use as part of the mainline Helsinki City Rail Loop.

- Kaisaniemi (Helsingin Yliopisto)

- A second area exists below the current platforms, with the intention to allow for future expansion.[46]

- Munkkivuori

- The designers of Finland's first shopping centre were very enthusiastic about the rumoured plans for a metro system all over Helsinki – something that would not appear for another 20 years. Built in 1964, the station does not fit into any plans of future metro lines and is unlikely to be ever used. The platform area is partially littered with building-rubble from more recent construction works in the area and the only visible evidence of the ahead-of-its-time station are a pair of large escalators. The escalators lead down from the main part of the shopping mall to the below-ground area where the ticket office would have been. The entrance to the lower level is behind the strange-shaped photographic shop.[47]

- Pasila

- A metro station was excavated under the Mall of Tripla shopping center. It is not known whether the station will ever be actually used as a metro station. The rationale behind constructing it was that it was cheaper and easier to do it while the mall was being constructed on top of it than to build it under an existing shopping center in the future. The possibility of a Pasila metro line will be considered some time after the year 2036. Meanwhile the metro station will be used for activities such as beach volley and indoor surfing.[48]

Statistics

According to the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority (HSL) yearly report for 2017, the metro system had a total of 65.5 million passengers.[49] According to the yearly report for 2003, the total turnover for the metro division of Helsinki City Transport (HKL) was €16.9 million and it made a profit of €3.8 million.

The Metro is by far the cheapest form of transport in Helsinki to operate, with a cost of only €0.032 per passenger kilometre. The same figure for the second cheapest form – trams – was €0.211.

In 2002, the Metro used 39.8 GWh of electricity, though the figure was rising (from 32.2 GWh in 2001). This equals 0.10 kWh per passenger kilometre, and compares favourably with Helsinki's trams (which used 0.19 kWh per passenger kilometre in 2002).[50]

See also

- Geography of Helsinki

- Helsinki Metropolitan Area

- List of Helsinki metro stations

- List of metro systems

- Public transport in Helsinki

References

- "By metro". City of Helsinki, Helsinki City Transport. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- "Metron käyttäjämäärät kasvussa – alkuhuuma kuitenkin hiipui nopeasti". www.tekniikkatalous.fi. 23 November 2017.

- "Metroasemien käyttäjämäärät". hel.fi. 20 October 2018.

- "Helsinki City Transport - About HKL - History - A brief history of the metro". Helsinki City Transport. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "By metro >> Track and depot". City of Helsinki, Helsinki City Transport. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "Helsinki metro cars". SRS. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- "Metroliikenne". Helsingin kaupunki (in Finnish). 18 July 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Helsinki City Transport - HKL Metro". Helsinki City Transport. 28 August 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Tolmunen, Tapio (2007). Tunnelijunasta suosikiksi - Helsingin metro 25 vuotta (in Finnish). Helsinki: Helsingin kaupungin liikennelaitos. pp. 7, 11. ISBN 978-952-5640-05-2.

- Alku, Antero (2002). Raitiovaunu tulee taas (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustantaja Laaksonen. pp. 24–26. ISBN 951-98475-3-7.

- Tolmunen. p. 19, 22–23.

- Tolmunen. p. 16.

- Alku. p. 37.

- Tolmunen. p. 26.

- "Metro Helsinki, historic survey". Finnish Tramway Society. 3 May 2010. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- "HKL Metro Transport: Metro EMU's M1 - M6". Finnish Tramway Society. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Tolmunen. p. 46.

- Tolmunen. p. 29, 33, 37.

- Tolmunen. p. 40.

- Grove, Thomas (14 July 2017). "Beneath Helsinki, Finns Prepare for Russian Threat". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Tolmunen. p. 54, 67.

- Tolmunen. p. 43.

- Tolmunen. p. 61–63.

- Tolmunen. p. 67.

- Tolmunen. p. 77–79, 82–83.

- "HKL Metro Transport: Metro EMU's M200". Finnish Tramway Society. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Alku. p. 31.

- Tolmunen. p. 87.

- länsimetro.fi FAQ Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- "Ruoholahden ja Kampin asemille pääsee taas metrolla". Helsinki Sanomat (in Finnish). 2009-11-11. Archived from the original on 2009-11-12. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- "Helsinki's Busiest Underground Station Reopens After Flood". Helsinki Times. 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- "Rautatientorin metroaseman hissit käyttöön". Helsingin Sanomat. 2010-06-21. Archived from the original on 2010-06-24. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- https://www.iltalehti.fi/kotimaa/a/67c63dc4-a464-416c-a217-2101453006b5

- https://www.hsl.fi/uutiset/2020/rautatientorin-metroaseman-laituritason-hissit-otetaan-kayttoon-173-19391

- "The construction work begins". lansimetro.fi. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- "Metro upgrades". Helsingin kaupunki.

- "Metroliikenne 18.11.2017 alkaen" (in Finnish). Helsinki Regional Transport Authority. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "Metro laajeni Matinkylään 18.11.2017".

- "Uudessa metrossa 90 metriä avointa tilaa – liikenne alkaa linjoilla M1 ja M2". Yle Uutiset.

- "Tickets and fares". HSL. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- "Länsimetro (English)". Lansimetro.fi. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- "Helsinki expanding eastwards". YLE. 25 October 2018.

- Helsingin Sanomat. "Helsingin valtuusto päätti metron automatisoinnista - HS.fi - Kaupunki". HS.fi. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- "Helsingin kaupunki". Hel.fi. Archived from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- Salonen, Juha (2005-02-05). "Seed of new subway line sprouting in basement of Kamppi complex". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08.

- Salonen, Juha (2005-02-13). "From the westbound line to the airport". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08.

- Hannula, Tommi (2007-09-17). "Juna ei saavu koskaan ensimmäiselle metroasemalle (First Metro station will never be used)". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- Minja Rantavaara (2019-04-29). "Helsingin uusimman ostoskeskuksen kellariin rakennetaan metroasemaa, jota ei ehkä koskaan tulla käyttämään". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 2019-04-29. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- "HSL Annual Report 2017". Helsinki Region Transport (HSL). sec. 4. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "Helsinki City Transport – a key player in a sustainable city" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Helsinki Metro. |

- HKL Metro - Official Site (in English)

- Helsinki City Transport (in Finnish)

- Metro website of the Finnish Tramway Society

- Helsinki at UrbanRail.net

- Photos of the Metro of Helsinki

- Pictures of Helsinki Metro

- Helsinki Metro Map