Spider

Spiders (order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom,[2] and spinnerets that extrude silk.[3] They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species diversity among all orders of organisms.[4] Spiders are found worldwide on every continent except for Antarctica, and have become established in nearly every habitat with the exceptions of air and sea colonization. As of July 2019, at least 48,200 spider species, and 120 families have been recorded by taxonomists.[1] However, there has been dissension within the scientific community as to how all these families should be classified, as evidenced by the over 20 different classifications that have been proposed since 1900.[5]

| Spiders | |

|---|---|

| |

| An assortment of different spiders. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Araneae Clerck, 1757 |

| Suborders | |

| Diversity[1] | |

| 120 families, c. 48,000 species | |

Anatomically, spiders (as with all arachnids) differ from other arthropods in that the usual body segments are fused into two tagmata, the prosoma, or cephalothorax, and opisthosoma, or abdomen, and joined by a small, cylindrical pedicel (however, as there is currently neither paleontological nor embryological evidence that spiders ever had a separate thorax-like division, there exists an argument against the validity of the term cephalothorax, which means fused cephalon (head) and the thorax. Similarly, arguments can be formed against use of the term abdomen, as the opisthosoma of all spiders contains a heart and respiratory organs, organs atypical of an abdomen[6]). Unlike insects, spiders do not have antennae. In all except the most primitive group, the Mesothelae, spiders have the most centralized nervous systems of all arthropods, as all their ganglia are fused into one mass in the cephalothorax. Unlike most arthropods, spiders have no extensor muscles in their limbs and instead extend them by hydraulic pressure.

Their abdomens bear appendages that have been modified into spinnerets that extrude silk from up to six types of glands. Spider webs vary widely in size, shape and the amount of sticky thread used. It now appears that the spiral orb web may be one of the earliest forms, and spiders that produce tangled cobwebs are more abundant and diverse than orb-web spiders. Spider-like arachnids with silk-producing spigots appeared in the Devonian period about 386 million years ago, but these animals apparently lacked spinnerets. True spiders have been found in Carboniferous rocks from 318 to 299 million years ago, and are very similar to the most primitive surviving suborder, the Mesothelae. The main groups of modern spiders, Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae, first appeared in the Triassic period, before 200 million years ago.

The species Bagheera kiplingi was described as herbivorous in 2008,[7] but all other known species are predators, mostly preying on insects and on other spiders, although a few large species also take birds and lizards. It is estimated that the world's 25 million tons of spiders kill 400–800 million tons of prey per year.[8] Spiders use a wide range of strategies to capture prey: trapping it in sticky webs, lassoing it with sticky bolas, mimicking the prey to avoid detection, or running it down. Most detect prey mainly by sensing vibrations, but the active hunters have acute vision, and hunters of the genus Portia show signs of intelligence in their choice of tactics and ability to develop new ones. Spiders' guts are too narrow to take solids, so they liquefy their food by flooding it with digestive enzymes. They also grind food with the bases of their pedipalps, as arachnids do not have the mandibles that crustaceans and insects have.

To avoid being eaten by the females, which are typically much larger, male spiders identify themselves to potential mates by a variety of complex courtship rituals. Males of most species survive a few matings, limited mainly by their short life spans. Females weave silk egg-cases, each of which may contain hundreds of eggs. Females of many species care for their young, for example by carrying them around or by sharing food with them. A minority of species are social, building communal webs that may house anywhere from a few to 50,000 individuals. Social behavior ranges from precarious toleration, as in the widow spiders, to co-operative hunting and food-sharing. Although most spiders live for at most two years, tarantulas and other mygalomorph spiders can live up to 25 years in captivity.

While the venom of a few species is dangerous to humans, scientists are now researching the use of spider venom in medicine and as non-polluting pesticides. Spider silk provides a combination of lightness, strength and elasticity that is superior to that of synthetic materials, and spider silk genes have been inserted into mammals and plants to see if these can be used as silk factories. As a result of their wide range of behaviors, spiders have become common symbols in art and mythology symbolizing various combinations of patience, cruelty and creative powers. An abnormal fear of spiders is called arachnophobia.

Description

Body plan

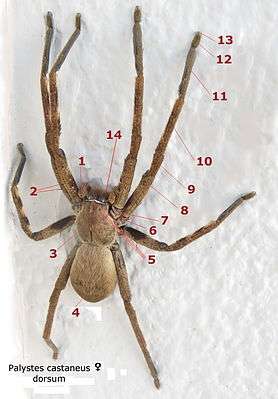

dorsal aspect

1: pedipalp

2: trichobothria

3: carapace of prosoma (cephalothorax)

4: opisthosoma (abdomen)

5: eyes – AL (anterior lateral)

AM (anterior median)

PL (posterior lateral)

PM (posterior median)

Leg segments:

6: costa

7: trochanter

8: patella

9: tibia

10: metatarsus

11: tarsus

13: claw

14: chelicera

15: sternum of prosoma

16: pedicel (also called pedicle)

17: book lung sac

18: book lung stigma

19: epigastric fold

20: epigyne

21: anterior spinneret

22: posterior spinneret

Spiders are chelicerates and therefore arthropods.[9] As arthropods they have: segmented bodies with jointed limbs, all covered in a cuticle made of chitin and proteins; heads that are composed of several segments that fuse during the development of the embryo.[10] Being chelicerates, their bodies consist of two tagmata, sets of segments that serve similar functions: the foremost one, called the cephalothorax or prosoma, is a complete fusion of the segments that in an insect would form two separate tagmata, the head and thorax; the rear tagma is called the abdomen or opisthosoma.[9] In spiders, the cephalothorax and abdomen are connected by a small cylindrical section, the pedicel.[11] The pattern of segment fusion that forms chelicerates' heads is unique among arthropods, and what would normally be the first head segment disappears at an early stage of development, so that chelicerates lack the antennae typical of most arthropods. In fact, chelicerates' only appendages ahead of the mouth are a pair of chelicerae, and they lack anything that would function directly as "jaws".[10][12] The first appendages behind the mouth are called pedipalps, and serve different functions within different groups of chelicerates.[9]

Spiders and scorpions are members of one chelicerate group, the arachnids.[12] Scorpions' chelicerae have three sections and are used in feeding.[13] Spiders' chelicerae have two sections and terminate in fangs that are generally venomous, and fold away behind the upper sections while not in use. The upper sections generally have thick "beards" that filter solid lumps out of their food, as spiders can take only liquid food.[11] Scorpions' pedipalps generally form large claws for capturing prey,[13] while those of spiders are fairly small appendages whose bases also act as an extension of the mouth; in addition, those of male spiders have enlarged last sections used for sperm transfer.[11]

In spiders, the cephalothorax and abdomen are joined by a small, cylindrical pedicel, which enables the abdomen to move independently when producing silk. The upper surface of the cephalothorax is covered by a single, convex carapace, while the underside is covered by two rather flat plates. The abdomen is soft and egg-shaped. It shows no sign of segmentation, except that the primitive Mesothelae, whose living members are the Liphistiidae, have segmented plates on the upper surface.[11]

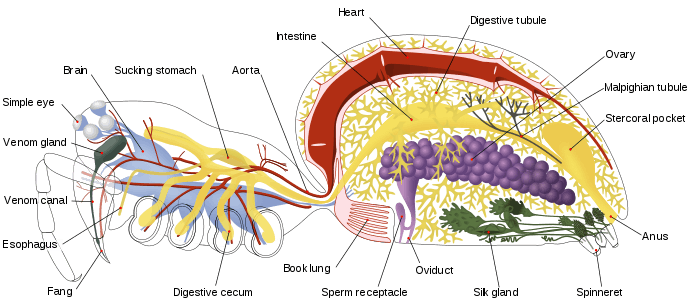

Circulation and respiration

Like other arthropods, spiders are coelomates in which the coelom is reduced to small areas round the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood flows. The heart is a tube in the upper part of the body, with a few ostia that act as non-return valves allowing blood to enter the heart from the hemocoel but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front end.[14] However, in spiders, it occupies only the upper part of the abdomen, and blood is discharged into the hemocoel by one artery that opens at the rear end of the abdomen and by branching arteries that pass through the pedicle and open into several parts of the cephalothorax. Hence spiders have open circulatory systems.[11] The blood of many spiders that have book lungs contains the respiratory pigment hemocyanin to make oxygen transport more efficient.[12]

Spiders have developed several different respiratory anatomies, based on book lungs, a tracheal system, or both. Mygalomorph and Mesothelae spiders have two pairs of book lungs filled with haemolymph, where openings on the ventral surface of the abdomen allow air to enter and diffuse oxygen. This is also the case for some basal araneomorph spiders, like the family Hypochilidae, but the remaining members of this group have just the anterior pair of book lungs intact while the posterior pair of breathing organs are partly or fully modified into tracheae, through which oxygen is diffused into the haemolymph or directly to the tissue and organs.[11] The tracheal system has most likely evolved in small ancestors to help resist desiccation.[12] The trachea were originally connected to the surroundings through a pair of openings called spiracles, but in the majority of spiders this pair of spiracles has fused into a single one in the middle, and moved backwards close to the spinnerets.[11] Spiders that have tracheae generally have higher metabolic rates and better water conservation.[15] Spiders are ectotherms, so environmental temperatures affect their activity.[16]

Feeding, digestion and excretion

Uniquely among chelicerates, the final sections of spiders' chelicerae are fangs, and the great majority of spiders can use them to inject venom into prey from venom glands in the roots of the chelicerae.[11] The families Uloboridae and Holarchaeidae, and some Liphistiidae spiders, have lost their venom glands, and kill their prey with silk instead.[17] Like most arachnids, including scorpions,[12] spiders have a narrow gut that can only cope with liquid food and two sets of filters to keep solids out.[11] They use one of two different systems of external digestion. Some pump digestive enzymes from the midgut into the prey and then suck the liquified tissues of the prey into the gut, eventually leaving behind the empty husk of the prey. Others grind the prey to pulp using the chelicerae and the bases of the pedipalps, while flooding it with enzymes; in these species, the chelicerae and the bases of the pedipalps form a preoral cavity that holds the food they are processing.[11]

The stomach in the cephalothorax acts as a pump that sends the food deeper into the digestive system. The midgut bears many digestive ceca, compartments with no other exit, that extract nutrients from the food; most are in the abdomen, which is dominated by the digestive system, but a few are found in the cephalothorax.[11]

Most spiders convert nitrogenous waste products into uric acid, which can be excreted as a dry material. Malphigian tubules ("little tubes") extract these wastes from the blood in the hemocoel and dump them into the cloacal chamber, from which they are expelled through the anus.[11] Production of uric acid and its removal via Malphigian tubules are a water-conserving feature that has evolved independently in several arthropod lineages that can live far away from water,[18] for example the tubules of insects and arachnids develop from completely different parts of the embryo.[12] However, a few primitive spiders, the suborder Mesothelae and infraorder Mygalomorphae, retain the ancestral arthropod nephridia ("little kidneys"),[11] which use large amounts of water to excrete nitrogenous waste products as ammonia.[18]

Central nervous system

The basic arthropod central nervous system consists of a pair of nerve cords running below the gut, with paired ganglia as local control centers in all segments; a brain formed by fusion of the ganglia for the head segments ahead of and behind the mouth, so that the esophagus is encircled by this conglomeration of ganglia.[19] Except for the primitive Mesothelae, of which the Liphistiidae are the sole surviving family, spiders have the much more centralized nervous system that is typical of arachnids: all the ganglia of all segments behind the esophagus are fused, so that the cephalothorax is largely filled with nervous tissue and there are no ganglia in the abdomen;[11][12][19] in the Mesothelae, the ganglia of the abdomen and the rear part of the cephalothorax remain unfused.[15]

Despite the relatively small central nervous system, some spiders (like Portia) exhibit complex behaviour, including the ability to use a trial-and-error approach.[20][21]

Sense organs

Eyes

Spiders have primarily four pairs of eyes on the top-front area of the cephalothorax, arranged in patterns that vary from one family to another.[11] The principal pair at the front are of the type called pigment-cup ocelli ("little eyes"), which in most arthropods are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, in spiders these eyes are capable of forming images.[22][23] The other pairs, called secondary eyes, are thought to be derived from the compound eyes of the ancestral chelicerates, but no longer have the separate facets typical of compound eyes. Unlike the principal eyes, in many spiders these secondary eyes detect light reflected from a reflective tapetum lucidum, and wolf spiders can be spotted by torchlight reflected from the tapeta. On the other hand, jumping spiders' secondary eyes have no tapeta.[11]

Other differences between the principal and secondary eyes are that the latter have rhabdomeres that point away from incoming light, just like in vertebrates, while the arrangement is the opposite in the former. The principal eyes are also the only ones with eye muscles, allowing them to move the retina. Having no muscles, the secondary eyes are immobile.[24]

Some jumping spiders' visual acuity exceeds by a factor of ten that of dragonflies, which have by far the best vision among insects; in fact the human eye is only about five times sharper than a jumping spider's. They achieve this by a telephotographic series of lenses, a four-layer retina and the ability to swivel their eyes and integrate images from different stages in the scan. The downside is that the scanning and integrating processes are relatively slow.[20]

There are spiders with a reduced number of eyes. Of these, those with six eyes (such as Periegops suterii) are the most numerous and are missing a pair of eyes on the anterior median line;[25] other species have four eyes and some just two. Cave dwelling species have no eyes, or possess vestigial eyes incapable of sight.

Other senses

As with other arthropods, spiders' cuticles would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, spiders and other arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly bristles called setae, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste and smell, often by means of setae.[22] An adult Araneus may have up to 1,000 such chemosensitive setae, most on the tarsi of the first pair of legs. Males have more chemosensitive bristles on their pedipalps than females. They have been shown to be responsive to sex pheromones produced by females, both contact and air-borne.[26] The jumping spider Evarcha culicivora uses the scent of blood from mammals and other vertebrates, which is obtained by capturing blood-filled mosquitoes, to attract the opposite sex. Because they are able to tell the sexes apart, it is assumed the blood scent is mixed with pheromones.[27] Spiders also have in the joints of their limbs slit sensillae that detect force and vibrations. In web-building spiders, all these mechanical and chemical sensors are more important than the eyes, while the eyes are most important to spiders that hunt actively.[11]

Like most arthropods, spiders lack balance and acceleration sensors and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. Arthropods' proprioceptors, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well-understood. On the other hand, little is known about what other internal sensors spiders or other arthropods may have.[22]

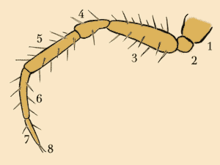

Locomotion

Each of the eight legs of a spider consists of seven distinct parts. The part closest to and attaching the leg to the cephalothorax is the coxa; the next segment is the short trochanter that works as a hinge for the following long segment, the femur; next is the spider's knee, the patella, which acts as the hinge for the tibia; the metatarsus is next, and it connects the tibia to the tarsus (which may be thought of as a foot of sorts); the tarsus ends in a claw made up of either two or three points, depending on the family to which the spider belongs. Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, spiders and a few other groups still use hydraulic pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors.[28] The only extensor muscles in spider legs are located in the three hip joints (bordering the coxa and the trochanter).[29] As a result, a spider with a punctured cephalothorax cannot extend its legs, and the legs of dead spiders curl up.[11] Spiders can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level to extend their legs,[30] and jumping spiders can jump up to 50 times their own length by suddenly increasing the blood pressure in the third or fourth pair of legs.[11] Although larger spiders use hydraulics to straighten their legs, unlike smaller jumping spiders they depend on their flexor muscles to generate the propulsive force for their jumps.[29]

Most spiders that hunt actively, rather than relying on webs, have dense tufts of fine bristles between the paired claws at the tips of their legs. These tufts, known as scopulae, consist of bristles whose ends are split into as many as 1,000 branches, and enable spiders with scopulae to walk up vertical glass and upside down on ceilings. It appears that scopulae get their grip from contact with extremely thin layers of water on surfaces.[11] Spiders, like most other arachnids, keep at least four legs on the surface while walking or running.[31]

Silk production

The abdomen has no appendages except those that have been modified to form one to four (usually three) pairs of short, movable spinnerets, which emit silk. Each spinneret has many spigots, each of which is connected to one silk gland. There are at least six types of silk gland, each producing a different type of silk.[11]

Silk is mainly composed of a protein very similar to that used in insect silk. It is initially a liquid, and hardens not by exposure to air but as a result of being drawn out, which changes the internal structure of the protein.[32] It is similar in tensile strength to nylon and biological materials such as chitin, collagen and cellulose, but is much more elastic. In other words, it can stretch much further before breaking or losing shape.[11]

Some spiders have a cribellum, a modified spinneret with up to 40,000 spigots, each of which produces a single very fine fiber. The fibers are pulled out by the calamistrum, a comblike set of bristles on the jointed tip of the cribellum, and combined into a composite woolly thread that is very effective in snagging the bristles of insects. The earliest spiders had cribella, which produced the first silk capable of capturing insects, before spiders developed silk coated with sticky droplets. However, most modern groups of spiders have lost the cribellum.[11]

Even species that do not build webs to catch prey use silk in several ways: as wrappers for sperm and for fertilized eggs; as a "safety rope"; for nest-building; and as "parachutes" by the young of some species.[11]

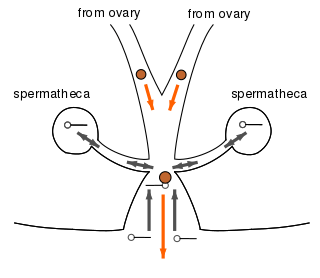

Reproduction and life cycle

Spiders reproduce sexually and fertilization is internal but indirect, in other words the sperm is not inserted into the female's body by the male's genitals but by an intermediate stage. Unlike many land-living arthropods,[33] male spiders do not produce ready-made spermatophores (packages of sperm), but spin small sperm webs onto which they ejaculate and then transfer the sperm to special syringe-styled structures, palpal bulbs or palpal organs, borne on the tips of the pedipalps of mature males. When a male detects signs of a female nearby he checks whether she is of the same species and whether she is ready to mate; for example in species that produce webs or "safety ropes", the male can identify the species and sex of these objects by "smell".[11]

Spiders generally use elaborate courtship rituals to prevent the large females from eating the small males before fertilization, except where the male is so much smaller that he is not worth eating. In web-weaving species, precise patterns of vibrations in the web are a major part of the rituals, while patterns of touches on the female's body are important in many spiders that hunt actively, and may "hypnotize" the female. Gestures and dances by the male are important for jumping spiders, which have excellent eyesight. If courtship is successful, the male injects his sperm from the palpal bulbs into the female via one or two openings on the underside of her abdomen.[11]

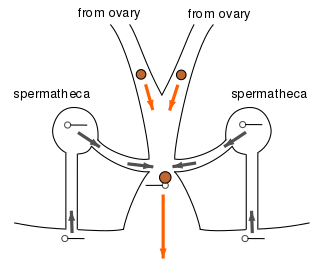

Female spiders' reproductive tracts are arranged in one of two ways. The ancestral arrangement ("haplogyne" or "non-entelegyne") consists of a single genital opening, leading to two seminal receptacles (spermathecae) in which females store sperm. In the more advanced arrangement ("entelegyne" ), there are two further openings leading directly to the spermathecae, creating a "flow through" system rather than a "first-in first-out" one. Eggs are as a general rule only fertilized during oviposition when the stored sperm is released from its chamber, rather than in the ovarian cavity.[34] A few exceptions exist, such as Parasteatoda tepidariorum. In these species the female appears to be able to activate the dormant sperm before oviposition, allowing them to migrate to the ovarian cavity where fertilization occurs.[35][36][37] The only known example of direct fertilization between male and female is an Israeli spider, Harpactea sadistica, which has evolved traumatic insemination. In this species the male will penetrate its pedipalps through the female's body wall and inject his sperm directly into her ovaries, where the embryos inside the fertilized eggs will start to develop before being laid.[38]

Males of the genus Tidarren amputate one of their palps before maturation and enter adult life with one palp only. The palps are 20% of the male's body mass in this species, and detaching one of the two improves mobility. In the Yemeni species Tidarren argo, the remaining palp is then torn off by the female. The separated palp remains attached to the female's epigynum for about four hours and apparently continues to function independently. In the meantime, the female feeds on the palpless male.[39] In over 60% of cases, the female of the Australian redback spider kills and eats the male after it inserts its second palp into the female's genital opening; in fact, the males co-operate by trying to impale themselves on the females' fangs. Observation shows that most male redbacks never get an opportunity to mate, and the "lucky" ones increase the likely number of offspring by ensuring that the females are well-fed.[40] However, males of most species survive a few matings, limited mainly by their short life spans. Some even live for a while in their mates' webs.[41]

The tiny male of the Golden orb weaver (Trichonephila clavipes) (near the top of the leaf) is protected from the female by producing the right vibrations in the web, and may be too small to be worth eating.

The tiny male of the Golden orb weaver (Trichonephila clavipes) (near the top of the leaf) is protected from the female by producing the right vibrations in the web, and may be too small to be worth eating. Orange spider egg sac hanging from ceiling

Orange spider egg sac hanging from ceiling Gasteracantha mammosa spiderlings next to their eggs capsule

Gasteracantha mammosa spiderlings next to their eggs capsule Wolf spider carrying its young on its abdomen

Wolf spider carrying its young on its abdomen

Females lay up to 3,000 eggs in one or more silk egg sacs,[11] which maintain a fairly constant humidity level.[41] In some species, the females die afterwards, but females of other species protect the sacs by attaching them to their webs, hiding them in nests, carrying them in the chelicerae or attaching them to the spinnerets and dragging them along.[11]

Baby spiders pass all their larval stages inside the egg and hatch as spiderlings, very small and sexually immature but similar in shape to adults. Some spiders care for their young, for example a wolf spider's brood clings to rough bristles on the mother's back,[11] and females of some species respond to the "begging" behaviour of their young by giving them their prey, provided it is no longer struggling, or even regurgitate food.[41]

Like other arthropods, spiders have to molt to grow as their cuticle ("skin") cannot stretch.[42] In some species males mate with newly-molted females, which are too weak to be dangerous to the males.[41] Most spiders live for only one to two years, although some tarantulas can live in captivity for over 20 years,[11][43] and an Australian female trapdoor spider was documented to have lived in the wild for 43 years, dying of a parasitic wasp attack.[44]

Size

Spiders occur in a large range of sizes. The smallest, Patu digua from Colombia, are less than 0.37 mm (0.015 in) in body length. The largest and heaviest spiders occur among tarantulas, which can have body lengths up to 90 mm (3.5 in) and leg spans up to 250 mm (9.8 in).[45]

Coloration

Only three classes of pigment (ommochromes, bilins and guanine) have been identified in spiders, although other pigments have been detected but not yet characterized. Melanins, carotenoids and pterins, very common in other animals, are apparently absent. In some species, the exocuticle of the legs and prosoma is modified by a tanning process, resulting in a brown coloration.[46] Bilins are found, for example, in Micrommata virescens, resulting in its green color. Guanine is responsible for the white markings of the European garden spider Araneus diadematus. It is in many species accumulated in specialized cells called guanocytes. In genera such as Tetragnatha, Leucauge, Argyrodes or Theridiosoma, guanine creates their silvery appearance. While guanine is originally an end-product of protein metabolism, its excretion can be blocked in spiders, leading to an increase in its storage.[46] Structural colors occur in some species, which are the result of the diffraction, scattering or interference of light, for example by modified setae or scales. The white prosoma of Argiope results from bristles reflecting the light, Lycosa and Josa both have areas of modified cuticle that act as light reflectors.[46]

While in many spiders color is fixed throughout their lifespan, in some groups, color may be variable in response to environmental and internal conditions.[46] Choice of prey may be able to alter the color of spiders. For example, the abdomen of Theridion grallator will become orange if the spider ingests certain species of Diptera and adult Lepidoptera, but if it consumes Homoptera or larval Lepidoptera, then the abdomen becomes green.[47] Environmentally induced color changes may be morphological (occurring over several days) or physiological (occurring near instantly). Morphological changes require pigment synthesis and degradation. In contrast to this, physiological changes occur by changing the position of pigment-containing cells.[46] An example of morphological color changes is background matching. Misumena vatia for instance can change its body color to match the substrate it lives on which makes it more difficult to be detected by prey.[48] An example of physiological color change is observed in Cyrtophora cicatrosa, which can change its body color from white to brown near instantly.[46]

Ecology and behavior

Non-predatory feeding

Although spiders are generally regarded as predatory, the jumping spider Bagheera kiplingi gets over 90% of its food from fairly solid plant material produced by acacias as part of a mutually beneficial relationship with a species of ant.[49]

Juveniles of some spiders in the families Anyphaenidae, Corinnidae, Clubionidae, Thomisidae and Salticidae feed on plant nectar. Laboratory studies show that they do so deliberately and over extended periods, and periodically clean themselves while feeding. These spiders also prefer sugar solutions to plain water, which indicates that they are seeking nutrients. Since many spiders are nocturnal, the extent of nectar consumption by spiders may have been underestimated. Nectar contains amino acids, lipids, vitamins and minerals in addition to sugars, and studies have shown that other spider species live longer when nectar is available. Feeding on nectar avoids the risks of struggles with prey, and the costs of producing venom and digestive enzymes.[50]

Various species are known to feed on dead arthropods (scavenging), web silk, and their own shed exoskeletons. Pollen caught in webs may also be eaten, and studies have shown that young spiders have a better chance of survival if they have the opportunity to eat pollen. In captivity, several spider species are also known to feed on bananas, marmalade, milk, egg yolk and sausages.[50]

Capturing prey

The best-known method of prey capture is by means of sticky webs. Varying placement of webs allows different species of spider to trap different insects in the same area, for example flat horizontal webs trap insects that fly up from vegetation underneath while flat vertical webs trap insects in horizontal flight. Web-building spiders have poor vision, but are extremely sensitive to vibrations.[11]

Females of the water spider Argyroneta aquatica build underwater "diving bell" webs that they fill with air and use for digesting prey, molting, mating and raising offspring. They live almost entirely within the bells, darting out to catch prey animals that touch the bell or the threads that anchor it.[51] A few spiders use the surfaces of lakes and ponds as "webs", detecting trapped insects by the vibrations that these cause while struggling.[11]

Net-casting spiders weave only small webs, but then manipulate them to trap prey. Those of the genus Hyptiotes and the family Theridiosomatidae stretch their webs and then release them when prey strike them, but do not actively move their webs. Those of the family Deinopidae weave even smaller webs, hold them outstretched between their first two pairs of legs, and lunge and push the webs as much as twice their own body length to trap prey, and this move may increase the webs' area by a factor of up to ten. Experiments have shown that Deinopis spinosus has two different techniques for trapping prey: backwards strikes to catch flying insects, whose vibrations it detects; and forward strikes to catch ground-walking prey that it sees. These two techniques have also been observed in other deinopids. Walking insects form most of the prey of most deinopids, but one population of Deinopis subrufa appears to live mainly on tipulid flies that they catch with the backwards strike.[52]

Mature female bolas spiders of the genus Mastophora build "webs" that consist of only a single "trapeze line", which they patrol. They also construct a bolas made of a single thread, tipped with a large ball of very wet sticky silk. They emit chemicals that resemble the pheromones of moths, and then swing the bolas at the moths. Although they miss on about 50% of strikes, they catch about the same weight of insects per night as web-weaving spiders of similar size. The spiders eat the bolas if they have not made a kill in about 30 minutes, rest for a while, and then make new bolas.[53][54] Juveniles and adult males are much smaller and do not make bolas. Instead they release different pheromones that attract moth flies, and catch them with their front pairs of legs.[55]

.jpg)

The primitive Liphistiidae, the "trapdoor spiders" of the family Ctenizidae and many tarantulas are ambush predators that lurk in burrows, often closed by trapdoors and often surrounded by networks of silk threads that alert these spiders to the presence of prey.[15] Other ambush predators do without such aids, including many crab spiders,[11] and a few species that prey on bees, which see ultraviolet, can adjust their ultraviolet reflectance to match the flowers in which they are lurking.[46] Wolf spiders, jumping spiders, fishing spiders and some crab spiders capture prey by chasing it, and rely mainly on vision to locate prey.[11]

Some jumping spiders of the genus Portia hunt other spiders in ways that seem intelligent,[20] outflanking their victims or luring them from their webs. Laboratory studies show that Portia's instinctive tactics are only starting points for a trial-and-error approach from which these spiders learn very quickly how to overcome new prey species.[56] However, they seem to be relatively slow "thinkers", which is not surprising, as their brains are vastly smaller than those of mammalian predators.[20]

Ant-mimicking spiders face several challenges: they generally develop slimmer abdomens and false "waists" in the cephalothorax to mimic the three distinct regions (tagmata) of an ant's body; they wave the first pair of legs in front of their heads to mimic antennae, which spiders lack, and to conceal the fact that they have eight legs rather than six; they develop large color patches round one pair of eyes to disguise the fact that they generally have eight simple eyes, while ants have two compound eyes; they cover their bodies with reflective bristles to resemble the shiny bodies of ants. In some spider species, males and females mimic different ant species, as female spiders are usually much larger than males. Ant-mimicking spiders also modify their behavior to resemble that of the target species of ant; for example, many adopt a zig-zag pattern of movement, ant-mimicking jumping spiders avoid jumping, and spiders of the genus Synemosyna walk on the outer edges of leaves in the same way as Pseudomyrmex. Ant mimicry in many spiders and other arthropods may be for protection from predators that hunt by sight, including birds, lizards and spiders. However, several ant-mimicking spiders prey either on ants or on the ants' "livestock", such as aphids. When at rest, the ant-mimicking crab spider Amyciaea does not closely resemble Oecophylla, but while hunting it imitates the behavior of a dying ant to attract worker ants. After a kill, some ant-mimicking spiders hold their victims between themselves and large groups of ants to avoid being attacked.[57]

Defense

There is strong evidence that spiders' coloration is camouflage that helps them to evade their major predators, birds and parasitic wasps, both of which have good color vision. Many spider species are colored so as to merge with their most common backgrounds, and some have disruptive coloration, stripes and blotches that break up their outlines. In a few species, such as the Hawaiian happy-face spider, Theridion grallator, several coloration schemes are present in a ratio that appears to remain constant, and this may make it more difficult for predators to recognize the species. Most spiders are insufficiently dangerous or unpleasant-tasting for warning coloration to offer much benefit. However, a few species with powerful venom, large jaws or irritant bristles have patches of warning colors, and some actively display these colors when threatened.[46][58]

Many of the family Theraphosidae, which includes tarantulas and baboon spiders, have urticating hairs on their abdomens and use their legs to flick them at attackers. These bristles are fine setae (bristles) with fragile bases and a row of barbs on the tip. The barbs cause intense irritation but there is no evidence that they carry any kind of venom.[59] A few defend themselves against wasps by including networks of very robust threads in their webs, giving the spider time to flee while the wasps are struggling with the obstacles.[60] The golden wheeling spider, Carparachne aureoflava, of the Namibian desert escapes parasitic wasps by flipping onto its side and cartwheeling down sand dunes.[61]

Socialization

A few spider species that build webs live together in large colonies and show social behavior, although not as complex as in social insects. Anelosimus eximius (in the family Theridiidae) can form colonies of up to 50,000 individuals.[62] The genus Anelosimus has a strong tendency towards sociality: all known American species are social, and species in Madagascar are at least somewhat social.[63] Members of other species in the same family but several different genera have independently developed social behavior. For example, although Theridion nigroannulatum belongs to a genus with no other social species, T. nigroannulatum build colonies that may contain several thousand individuals that co-operate in prey capture and share food.[64] Other communal spiders include several Philoponella species (family Uloboridae), Agelena consociata (family Agelenidae) and Mallos gregalis (family Dictynidae).[65] Social predatory spiders need to defend their prey against kleptoparasites ("thieves"), and larger colonies are more successful in this.[66] The herbivorous spider Bagheera kiplingi lives in small colonies which help to protect eggs and spiderlings.[49] Even widow spiders (genus Latrodectus), which are notoriously cannibalistic, have formed small colonies in captivity, sharing webs and feeding together.[67]

Web types

There is no consistent relationship between the classification of spiders and the types of web they build: species in the same genus may build very similar or significantly different webs. Nor is there much correspondence between spiders' classification and the chemical composition of their silks. Convergent evolution in web construction, in other words use of similar techniques by remotely related species, is rampant. Orb web designs and the spinning behaviors that produce them are the best understood. The basic radial-then-spiral sequence visible in orb webs and the sense of direction required to build them may have been inherited from the common ancestors of most spider groups.[68] However, the majority of spiders build non-orb webs. It used to be thought that the sticky orb web was an evolutionary innovation resulting in the diversification of the Orbiculariae. Now, however, it appears that non-orb spiders are a subgroup that evolved from orb-web spiders, and non-orb spiders have over 40% more species and are four times as abundant as orb-web spiders. Their greater success may be because sphecid wasps, which are often the dominant predators of spiders, much prefer to attack spiders that have flat webs.[69]

Orb

About half the potential prey that hit orb webs escape. A web has to perform three functions: intercepting the prey (intersection), absorbing its momentum without breaking (stopping), and trapping the prey by entangling it or sticking to it (retention). No single design is best for all prey. For example: wider spacing of lines will increase the web's area and hence its ability to intercept prey, but reduce its stopping power and retention; closer spacing, larger sticky droplets and thicker lines would improve retention, but would make it easier for potential prey to see and avoid the web, at least during the day. However, there are no consistent differences between orb webs built for use during the day and those built for use at night. In fact, there is no simple relationship between orb web design features and the prey they capture, as each orb-weaving species takes a wide range of prey.[68]

The hubs of orb webs, where the spiders lurk, are usually above the center, as the spiders can move downwards faster than upwards. If there is an obvious direction in which the spider can retreat to avoid its own predators, the hub is usually offset towards that direction.[68]

Horizontal orb webs are fairly common, despite being less effective at intercepting and retaining prey and more vulnerable to damage by rain and falling debris. Various researchers have suggested that horizontal webs offer compensating advantages, such as reduced vulnerability to wind damage; reduced visibility to prey flying upwards, because of the backlighting from the sky; enabling oscillations to catch insects in slow horizontal flight. However, there is no single explanation for the common use of horizontal orb webs.[68]

Spiders often attach highly visible silk bands, called decorations or stabilimenta, to their webs. Field research suggests that webs with more decorative bands captured more prey per hour.[70] However, a laboratory study showed that spiders reduce the building of these decorations if they sense the presence of predators.[71]

There are several unusual variants of orb web, many of them convergently evolved, including: attachment of lines to the surface of water, possibly to trap insects in or on the surface; webs with twigs through their centers, possibly to hide the spiders from predators; "ladderlike" webs that appear most effective in catching moths. However, the significance of many variations is unclear.[68]

In 1973, Skylab 3 took two orb-web spiders into space to test their web-spinning capabilities in zero gravity. At first, both produced rather sloppy webs, but they adapted quickly.[72]

Cobweb

Members of the family Theridiidae weave irregular, tangled, three-dimensional webs, popularly known as cobwebs. There seems to be an evolutionary trend towards a reduction in the amount of sticky silk used, leading to its total absence in some species. The construction of cobwebs is less stereotyped than that of orb-webs, and may take several days.[69]

Other

The Linyphiidae generally make horizontal but uneven sheets, with tangles of stopping threads above. Insects that hit the stopping threads fall onto the sheet or are shaken onto it by the spider, and are held by sticky threads on the sheet until the spider can attack from below.[73]

Evolution

Fossil record

.jpg)

Although the fossil record of spiders is considered poor,[74] almost 1000 species have been described from fossils.[75] Because spiders' bodies are quite soft, the vast majority of fossil spiders have been found preserved in amber.[75] The oldest known amber that contains fossil arthropods dates from 130 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous period. In addition to preserving spiders' anatomy in very fine detail, pieces of amber show spiders mating, killing prey, producing silk and possibly caring for their young. In a few cases, amber has preserved spiders' egg sacs and webs, occasionally with prey attached;[76] the oldest fossil web found so far is 100 million years old.[77] Earlier spider fossils come from a few lagerstätten, places where conditions were exceptionally suited to preserving fairly soft tissues.[76]

The oldest known exclusively terrestrial arachnid is the trigonotarbid Palaeotarbus jerami, from about 420 million years ago in the Silurian period, and had a triangular cephalothorax and segmented abdomen, as well as eight legs and a pair of pedipalps.[78] Attercopus fimbriunguis, from 386 million years ago in the Devonian period, bears the earliest known silk-producing spigots, and was therefore hailed as a spider at the time of its discovery.[79] However, these spigots may have been mounted on the underside of the abdomen rather than on spinnerets, which are modified appendages and whose mobility is important in the building of webs. Hence Attercopus and the similar Permian arachnid Permarachne may not have been true spiders, and probably used silk for lining nests or producing egg cases rather than for building webs.[3] The largest known fossil spider as of 2011 is the araneid Nephila jurassica, from about 165 million years ago, recorded from Daohuogo, Inner Mongolia in China.[80] Its body length is almost 25 mm, (i.e., almost one inch).

Several Carboniferous spiders were members of the Mesothelae, a primitive group now represented only by the Liphistiidae.[79] The mesothelid Paleothele montceauensis, from the Late Carboniferous over 299 million years ago, had five spinnerets.[81] Although the Permian period 299 to 251 million years ago saw rapid diversification of flying insects, there are very few fossil spiders from this period.[79]

The main groups of modern spiders, Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae, first appear in the Triassic well before 200 million years ago. Some Triassic mygalomorphs appear to be members of the family Hexathelidae, whose modern members include the notorious Sydney funnel-web spider, and their spinnerets appear adapted for building funnel-shaped webs to catch jumping insects. Araneomorphae account for the great majority of modern spiders, including those that weave the familiar orb-shaped webs. The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods provide a large number of fossil spiders, including representatives of many modern families.[79]

Family tree

| Chelicerata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is now agreed that spiders (Araneae) are monophyletic (i.e., members of a group of organisms that form a clade, consisting of a last common ancestor and all of its descendants).[83] There has been debate about what their closest evolutionary relatives are, and how all of these evolved from the ancestral chelicerates, which were marine animals. The cladogram on the right is based on J. W. Shultz' analysis (2007). Other views include proposals that: scorpions are more closely related to the extinct marine scorpioid eurypterids than to spiders; spiders and Amblypygi are a monophyletic group. The appearance of several multi-way branchings in the tree on the right shows that there are still uncertainties about relationships between the groups involved.[83]

Arachnids lack some features of other chelicerates, including backward-pointing mouths and gnathobases ("jaw bases") at the bases of their legs;[83] both of these features are part of the ancestral arthropod feeding system.[84] Instead, they have mouths that point forwards and downwards, and all have some means of breathing air.[83] Spiders (Araneae) are distinguished from other arachnid groups by several characteristics, including spinnerets and, in males, pedipalps that are specially adapted for sperm transfer.[85]

Taxonomy

Spiders are divided into two suborders, Mesothelae and Opisthothelae, of which the latter contains two infraorders, Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae. Over 48,000 living species of spiders (order Araneae) have been identified and as of 2019 grouped into 120 families and about 4,100 genera by arachnologists.[1]

| Spider diversity[1][85] (numbers are approximate) | Features | ||||||

| Suborder/Infraorder | Families | Genera | Species | Segmented plates on top of abdomen[86] | Ganglia in abdomen | Spinnerets[86] | Striking direction of fangs[11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesothelae | 1 | 8 | 116 | Yes | Yes | Four pairs, in some species one pair fused, under middle of abdomen | Downwards and forwards |

| Opisthothelae: Mygalomorphae | 20 | 350 | 2,900 | Only in some fossils | No | One, two or three pairs under rear of abdomen | |

| Opisthothelae: Araneomorphae | 96 | 3,700 | 44,000 | From sides to center, like pincers | |||

Mesothelae

The only living members of the primitive Mesothelae are the family Liphistiidae, found only in Southeast Asia, China, and Japan.[85] Most of the Liphistiidae construct silk-lined burrows with thin trapdoors, although some species of the genus Liphistius build camouflaged silk tubes with a second trapdoor as an emergency exit. Members of the genus Liphistius run silk "tripwires" outwards from their tunnels to help them detect approaching prey, while those of the genus Heptathela do not and instead rely on their built-in vibration sensors.[88] Spiders of the genus Heptathela have no venom glands, although they do have venom gland outlets on the fang tip.[89]

The extinct families Arthrolycosidae, found in Carboniferous and Permian rocks, and Arthromygalidae, so far found only in Carboniferous rocks, have been classified as members of the Mesothelae.[90]

Mygalomorphae

The Mygalomorphae, which first appeared in the Triassic period,[79] are generally heavily built and ″hairy″, with large, robust chelicerae and fangs (technically, spiders do not have true hairs, but rather setae).[91][85] Well-known examples include tarantulas, ctenizid trapdoor spiders and the Australasian funnel-web spiders.[11] Most spend the majority of their time in burrows, and some run silk tripwires out from these, but a few build webs to capture prey. However, mygalomorphs cannot produce the pirifom silk that the Araneomorphae use as an instant adhesive to glue silk to surfaces or to other strands of silk, and this makes web construction more difficult for mygalomorphs. Since mygalomorphs rarely "balloon" by using air currents for transport, their populations often form clumps.[85] In addition to arthropods, some mygalomorphs are known to prey on frogs, small mammals, lizards, snakes, snails, and small birds.[92][93]

Araneomorphae

In addition to accounting for over 90% of spider species, the Araneomorphae, also known as the "true spiders", include orb-web spiders, the cursorial wolf spiders, and jumping spiders,[85] as well as the only known herbivorous spider, Bagheera kiplingi.[49] They are distinguished by having fangs that oppose each other and cross in a pinching action, in contrast to the Mygalomorphae, which have fangs that are nearly parallel in alignment.[94]

Human interaction

Bites

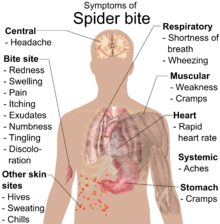

Although spiders are widely feared, only a few species are dangerous to people.[96] Spiders will only bite humans in self-defense, and few produce worse effects than a mosquito bite or bee sting.[97] Most of those with medically serious bites, such as recluse spiders (genus Loxosceles) and widow spiders (genus Latrodectus), would rather flee and bite only when trapped, although this can easily arise by accident.[98][99] The defensive tactics of Australian funnel-web spiders (family Atracidae) include fang display. Their venom, although they rarely inject much, has resulted in 13 attributed human deaths over 50 years.[100] They have been deemed to be the world's most dangerous spiders on clinical and venom toxicity grounds,[96] though this claim has also been attributed to the Brazilian wandering spider (genus Phoneutria).[101]

There were about 100 reliably reported deaths from spider bites in the 20th century,[102] compared to about 1,500 from jellyfish stings.[103] Many alleged cases of spider bites may represent incorrect diagnoses,[104] which would make it more difficult to check the effectiveness of treatments for genuine bites.[105] A review published in 2016 agreed with this conclusion, showing that 78% of 134 published medical case studies of supposed spider bites did not meet the necessary criteria for a spider bite to be verified. In the case of the two genera with the highest reported number of bites, Loxosceles and Latrodectus, spider bites were not verified in over 90% of the reports. Even when verification had occurred, details of the treatment and its effects were often lacking.[106]

Chemical benefits

Spider venoms may be a less polluting alternative to conventional pesticides, as they are deadly to insects but the great majority are harmless to vertebrates. Australian funnel web spiders are a promising source, as most of the world's insect pests have had no opportunity to develop any immunity to their venom, and funnel web spiders thrive in captivity and are easy to "milk". It may be possible to target specific pests by engineering genes for the production of spider toxins into viruses that infect species such as cotton bollworms.[107]

The Ch'ol Maya use a beverage created from the tarantula species Brachypelma vagans for the treatment of a condition they term 'tarantula wind', the symptoms of which include chest pain, asthma and coughing.[108]

Possible medical uses for spider venoms are being investigated, for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmia,[109] Alzheimer's disease,[110] strokes,[111] and erectile dysfunction.[112] The peptide GsMtx-4, found in the venom of Brachypelma vagans, is being researched to determine whether or not it could effectively be used for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmia, muscular dystrophy or glioma.[108] Because spider silk is both light and very strong, attempts are being made to produce it in goats' milk and in the leaves of plants, by means of genetic engineering.[113][114]

Spiders can also be used as food. Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia,[115] and by the Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela – provided the highly irritant bristles, the spiders' main defense system, are removed first.[116]

Arachnophobia

Arachnophobia is a specific phobia—it is the abnormal fear of spiders or anything reminiscent of spiders, such as webs or spiderlike shapes. It is one of the most common specific phobias,[117][118] and some statistics show that 50% of women and 10% of men show symptoms.[119] It may be an exaggerated form of an instinctive response that helped early humans to survive,[120] or a cultural phenomenon that is most common in predominantly European societies.[121]

Spiders in culture

Spiders have been the focus of stories and mythologies of various cultures for centuries.[122] Uttu, the ancient Sumerian goddess of weaving, was envisioned as a spider spinning her web.[123][124] According to her main myth, she resisted her father Enki's sexual advances by ensconcing herself in her web,[124] but let him in after he promised her fresh produce as a marriage gift,[124] thereby allowing him to intoxicate her with beer and rape her.[124] Enki's wife Ninhursag heard Uttu's screams and rescued her,[124] removing Enki's semen from her vagina and planting it in the ground to produce eight previously-nonexistent plants.[124] In a story told by the Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Arachne was a Lydian girl who challenged the goddess Athena to a weaving contest.[125][126] Arachne won, but Athena destroyed her tapestry out of jealousy,[126][127] causing Arachne to hang herself.[126][127] In an act of mercy, Athena brought Arachne back to life as the first spider.[126][127] Stories about the trickster-spider Anansi are prominent in the folktales of West Africa and the Caribbean.[128]

In some cultures, spiders have symbolized patience due to their hunting technique of setting webs and waiting for prey, as well as mischief and malice due to their venomous bites.[129] The Italian tarantella is a dance to rid the young woman of the lustful effects of a spider bite. Web-spinning also caused the association of the spider with creation myths, as they seem to have the ability to produce their own worlds.[130] Dreamcatchers are depictions of spiderwebs. The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature.[131] They placed emphasis on animals and often depicted spiders in their art.[132]

See also

Footnotes

- "Currently valid spider genera and species". World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- Cushing P.E. (2008) Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae). In: Capinera J.L. (eds) Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer, p. 3496. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6359-6_4320.

- Selden, P.A. & Shear, W.A. (December 2008). "Fossil evidence for the origin of spider spinnerets". PNAS. 105 (52): 20781–85. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520781S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809174106. PMC 2634869. PMID 19104044.

- Sebastin, P.A. & Peter, K.V. (eds.) (2009). Spiders of India. Universities Press/Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-7371-641-6

- Foelix, Rainer F. (1996). Biology of Spiders. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-509593-7.

- Shultz, Stanley; Shultz, Marguerite (2009). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- Meehan, Christopher J.; Olson, Eric J.; Reudink, Matthew W.; Kyser, T. Kurt; Curry, Robert L. (2009). "Herbivory in a spider through exploitation of an ant–plant mutualism". Current Biology. 19 (19): R892–93. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.049. PMID 19825348.

- Nyffeler, Martin; Birkhofer, Klaus (14 March 2017). "An estimated 400–800 million tons of prey are annually killed by the global spider community". The Science of Nature. 104 (30): 30. Bibcode:2017SciNa.104...30N. doi:10.1007/s00114-017-1440-1. PMC 5348567. PMID 28289774.

- Ruppert, 554–55

- Ruppert, 518–22

- Ruppert, 571–84

- Ruppert, 559–64

- Ruppert, 565–69

- Ruppert, 527–28

- Coddington, J.A. & Levi, H.W. (1991). "Systematics and Evolution of Spiders (Araneae)". Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 22: 565–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.003025.

- Barghusen, L.E.; Claussen, D.L.; Anderson, M.S.; Bailer, A.J. (1 February 1997). "The effects of temperature on the web-building behaviour of the common house spider, Achaearanea tepidariorum". Functional Ecology. 11 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1997.00040.x.

- "Spiders-Arañas – Dr. Sam Thelin". Drsamchapala.com. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Ruppert, 529–30

- Ruppert, 531–32

- Harland, D.P. & Jackson, R.R. (2000). ""Eight-legged cats" and how they see – a review of recent research on jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae)" (PDF). Cimbebasia. 16: 231–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Wilcox, R. Stimson; Jackson, Robert R. (1998). "Cognitive Abilities of Araneophagic Jumping Spiders". In Balda, Russell P.; Pepperberg, Irene M.; Kamil, Alan C. (eds.). Animal cognition in nature: the convergence of psychology and biology in laboratory and field. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-077030-4. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- Ruppert, 532–37

- Ruppert, 578–80

- Barth, Friedrich G. (2013). A Spider's World: Senses and Behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783662048993. Retrieved 31 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- Deeleman-Reinhold (2001), p. 27.

- Foelix, Rainer F. (2011). Biology of Spiders (3rd p/b ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 100–01. ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5.

- 'Vampire' spiders use blood as perfume | CBC News - CBC.ca

- Barnes, R.S.K.; Calow, P.; Olive, P.; Golding, D.; Spicer, J. (2001). "Invertebrates with Legs: the Arthropods and Similar Groups". The Invertebrates: A Synthesis. Blackwell Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1.

- Weihmann, Tom; Günther, Michael; Blickhan, Reinhard (2012-02-15). "Hydraulic Leg Extension Is Not Necessarily the Main Drive in Large Spiders". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (4): 578–83. doi:10.1242/jeb.054585. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 22279064.

- Parry, D.A. & Brown, R.H.J. (1959). "The Hydraulic Mechanism of the Spider Leg" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 36 (2): 423–33. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- Ruppert, 325–49

- Vollrath, F. & Knight, D.P. (2001). "Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk". Nature. 410 (6828): 541–48. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..541V. doi:10.1038/35069000. PMID 11279484.

- Ruppert, 537–39

- Foelix, Rainer F. (2011). Biology of Spiders (3rd p/b ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5.

- Fertilization occurs internally in the spider Achaearanea tepidariorum (C. Koch)

- Complex Genital System of a Haplogyne Spider (Arachnida, Araneae, Tetrablemmidae) Indicates Internal Fertilization and Full Female Control Over Transferred Sperm

- Structure and function of the female reproductive system in three species of goblin spiders (Arachnida: Araneae: Oonopidae)

- Rezác M (August 2009). "The spider Harpactea sadistica: co-evolution of traumatic insemination and complex female genital morphology in spiders". Proc. Biol. Sci. 276 (1668): 2697–701. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0104. PMC 2839943. PMID 19403531.

- Knoflach, B. & van Harten, A. (2001). "Tidarren argo sp. nov (Araneae: Theridiidae) and its exceptional copulatory behaviour: emasculation, male palpal organ as a mating plug and sexual cannibalism". Journal of Zoology. 254 (4): 449–59. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000954.

- Andrade, Maydianne C.B. (2003). "Risky mate search and male self-sacrifice in redback spiders". Behavioral Ecology. 14 (4): 531–38. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg015.

- Foelix, Rainer F. (1996). "Reproduction". Biology of Spiders (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press US. pp. 176–212. ISBN 978-0-19-509594-4.

- Ruppert, 523–24

- Foelix, Rainer F. (1996). Biology of Spiders. Oxford University Press. pp. 232–33. ISBN 978-0-674-07431-6.

- "World's oldest known spider dies at 43 after a quiet life underground". The Guardian. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Levi, Herbert W. and Levi, Lorna R. (2001) Spiders and their Kin, Golden Press, pp. 20, 44. ISBN 1582381569

- Oxford, G.S.; Gillespie, R.G. (1998). "Evolution and Ecology of Spider Coloration". Annual Review of Entomology. 43: 619–43. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.619. PMID 15012400.

- Gillespie, Rosemary G. (1989). "Diet-Induced Color Change in the Hawaiian Happy-Face Spider Theridion grallator, (Araneae, Theridiidae)". The Journal of Arachnology. 17 (2): 171–177. ISSN 0161-8202. JSTOR 3705625.

- Defrize, J.; Thery, M.; Casas, J. (2010-05-01). "Background colour matching by a crab spider in the field: a community sensory ecology perspective". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (9): 1425–1435. doi:10.1242/jeb.039743. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 20400626.

- Meehan, C.J.; Olson, E.J.; Curry, R.L. (21 August 2008). Exploitation of the Pseudomyrmex–Acacia mutualism by a predominantly vegetarian jumping spider (Bagheera kiplingi). 93rd ESA Annual Meeting. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Jackson, R.R.; Pollard, Simon D.; Nelson, Ximena J.; Edwards, G.B.; Barrion, Alberto T. (2001). "Jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) that feed on nectar" (PDF). J. Zool. Lond. 255: 25–29. doi:10.1017/S095283690100108X.

- Schütz, D. & Taborsky, M. (2003). "Adaptations to an aquatic life may be responsible for the reversed sexual size dimorphism in the water spider, Argyroneta aquatica" (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology Research. 5 (1): 105–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Coddington, J. & Sobrevila, C. (1987). "Web manipulation and two stereotyped attack behaviors in the ogre-faced spider Deinopis spinosus Marx (Araneae, Deinopidae)" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 15: 213–25. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Eberhard, W.G. (1977). "Aggressive Chemical Mimicry by a Bolas Spider" (PDF). Science. 198 (4322): 1173–75. Bibcode:1977Sci...198.1173E. doi:10.1126/science.198.4322.1173. PMID 17818935. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Eberhard, W.G. (1980). "The Natural History and Behavior of the Bolas Spider, Mastophora dizzydeani sp. n. (Araneae)". Psyche. 87 (3–4): 143–70. doi:10.1155/1980/81062. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Yeargan, K.V. & Quate, L.W. (1997). "Adult male bolas spiders retain juvenile hunting tactics". Oecologia. 112 (4): 572–76. Bibcode:1997Oecol.112..572Y. doi:10.1007/s004420050347. PMID 28307636.

- Wilcox, S. & Jackson, R. (2002). "Jumping Spider Tricksters" (PDF). In Bekoff, M.; Allen, C. & Burghardt, G.M. (eds.). The Cognitive Animal: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition. MIT Press. pp. 27–34. ISBN 978-0-262-52322-6. Retrieved 25 Mar 2011.

- Mclver, J.D. & Stonedahl, G. (1993). "Myrmecomorphy: Morphological and Behavioral Mimicry of Ants". Annual Review of Entomology. 38: 351–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.38.010193.002031.

- "Different smiles, single species". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Cooke, J.A.L.; Roth, V.D.; Miller, F.H. "The urticating hairs of theraphosid spiders". American Museum Novitates (2498). hdl:2246/2705.

- Blackledge, T.A. & Wenzel, J.W. (2001). "Silk Mediated Defense by an Orb Web Spider against Predatory Mud-dauber Wasps". Behaviour. 138 (2): 155–71. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.512.3868. doi:10.1163/15685390151074357.

- Armstrong, S. (14 July 1990). "Fog, wind and heat – life in the Namib desert". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Vollrath, F. (1986). "Eusociality and extraordinary sex ratios in the spider Anelosimus eximius (Araneae: Theridiidae)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 18 (4): 283–87. doi:10.1007/BF00300005.

- Agnarsson, I. & Kuntner, M. (2005). "Madagascar: an unexpected hotspot of social Anelosimus spider diversity (Araneae: Theridiidae)". Systematic Entomology. 30 (4): 575–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2005.00289.x.

- Avilés, L.; Maddison, W.P.; Agnarsson, I. (2006). "A New Independently Derived Social Spider with Explosive Colony Proliferation and a Female Size Dimorphism". Biotropica. 38 (6): 743–53. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00202.x.

- Matsumoto, T. (1998). "Cooperative prey capture in the communal web spider, Philoponella raffray (Araneae, Uloboridae)" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 26: 392–96. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Cangialosi, K.R. (1990). "Social spider defense against kleptoparasitism". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 27 (1). doi:10.1007/BF00183313.

- Bertani, R.; Fukushima, C. S.; Martins, R. (2008). "Sociable widow spiders? Evidence of subsociality in LatrodectusWalckenaer, 1805 (Araneae, Theridiidae)". Journal of Ethology. 26 (2): 299–302. doi:10.1007/s10164-007-0082-8.

- Eberhard, W.G. (1990). "Function and Phylogeny of Spider Webs" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 21: 341–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.002013. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- Agnarsson, I. (2004). "Morphological phylogeny of cobweb spiders and their relatives (Araneae, Araneoidea, Theridiidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 141 (4): 447–626. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00120.x.

- Herberstein, M.E. (2000). "Foraging behaviour in orb-web spiders (Araneidae): Do web decorations increase prey capture success in Argiope keyserlingi Karsch, 1878?". Australian Journal of Zoology. 48 (2): 217–23. doi:10.1071/ZO00007.

- Li, D. & Lee, W.S. (2004). "Predator-induced plasticity in web-building behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 67 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.011.

- Thomson, Peggy & Park, Edwards. "Odd Tales from the Smithsonian". Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- Schütt, K. (1995). "Drapetisca socialis (Araneae: Linyphiidae): Web reduction – ethological and morphological adaptations" (PDF). European Journal of Entomology. 92: 553–63. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Selden, P.A.; Anderson, H.M.; Anderson, J.M. (2009). "A review of the fossil record of spiders (Araneae) with special reference to Africa, and description of a new specimen from the Triassic Molteno Formation of South Africa". African Invertebrates. 50 (1): 105–16. doi:10.5733/afin.050.0103. Abstract Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine PDF

- Dunlop, Jason A.; David Penney; O. Erik Tetlie; Lyall I. Anderson (2008). "How many species of fossil arachnids are there?". The Journal of Arachnology. 36 (2): 267–72. doi:10.1636/CH07-89.1.

- Penney, D. & Selden, P.A. (2007). "Spinning with the dinosaurs: the fossil record of spiders". Geology Today. 23 (6): 231–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.2007.00641.x.

- Hecht, H. "Oldest spider web found in amber". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- Dunlop, J.A. (1996). "A trigonotarbid arachnid from the Upper Silurian of Shropshire" (PDF). Palaeontology. 39 (3): 605–14. Retrieved 2008-10-12. The fossil was originally named Eotarbus but was renamed when it was realized that a Carboniferous arachnid had already been named Eotarbus: Dunlop, J.A. (1999). "A replacement name for the trigonotarbid arachnid Eotarbus Dunlop". Palaeontology. 42 (1): 191. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00068.

- Vollrath, F. & Selden, P.A. (2007). "The Role of Behavior in the Evolution of Spiders, Silks, and Webs" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 38: 819–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110221. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- Selden, P.A.; ChungKun Shih; Dong Ren (2011). "A golden orb-weaver spider(Araneae: Nephilidae: Nephila) from the Middle Jurassic of China". Biology Letters. 7 (5): 775–78. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0228. PMC 3169061. PMID 21508021.

- Selden, P.A. (1996). "Fossil mesothele spiders". Nature. 379 (6565): 498–99. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..498S. doi:10.1038/379498b0.

- J. W. Shultz (2007). "A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 150: 221–265. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00284.x.

- Shultz, J.W. (2007). "A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 150 (2): 221–65. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00284.x.

- Gould, S.J. (1990). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Hutchinson Radius. pp. 102–06 [105]. Bibcode:1989wlbs.book.....G. ISBN 978-0-09-174271-3.

- Coddington, J.A. (2005). "Phylogeny and Classification of Spiders" (PDF). In Ubick, D.; Paquin, P.; Cushing, P.E.; Roth, V. (eds.). Spiders of North America: an identification manual. American Arachnological Society. pp. 18–24. ISBN 978-0-9771439-0-0. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- Leroy, J & Leroy, A. (2003). "How spiders function". Spiders of Southern Africa. Struik. pp. 15–21. ISBN 978-1-86872-944-9.

- Ono, H. (2002). "New and Remarkable Spiders of the Families Liphistiidae, Argyronetidae, Pisauridae, Theridiidae and Araneidae (Arachnida) from Japan". Bulletin of the National Science Museum (Of Japan), Series A. 28 (1): 51–60.

- Coyle, F.A. (1986). "The Role of Silk in Prey Capture". In Shear, W.A. (ed.). Spiders – webs, behavior, and evolution. Stanford University Press. pp. 272–73. ISBN 978-0-8047-1203-3.

- Forster, R.R. & Platnick, N.I. (1984). "A review of the archaeid spiders and their relatives, with notes on the limits of the superfamily Palpimanoidea (Arachnida, Araneae)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 178: 1–106. hdl:2246/991. Full text at "A review of the archaeid spiders and their relatives" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- Penney, D. & Selden, P.A. Deltshev, C. & Stoev, P. (eds.). "European Arachnology 2005" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. Supplement No. 1: 25–39. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

Assembling the Tree of Life –Phylogeny of Spiders: a review of the strictly fossil spider families

- Schultz, Stanley; Schultz, Marguerite (2009). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- Schultz, Stanley; Schultz, Margeurite (2009). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- "Natural history of Mygalomorphae". Agricultural Research Council of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- Foelix, Rainer F. (2011-05-05). Biology of Spiders (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5.

- Spider Bite Symptoms and First Aid By Rod Brouhard, About.com. Updated: October 19, 2008

- Vetter, Richard S.; Isbister, Geoffrey K. (2008). "Medical Aspects of Spider Bites". Annual Review of Entomology. 53: 409–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093503. PMID 17877450.

- "Spiders". Illinois Department of Public Health. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Vetter RS, Barger DK (2002). "An infestation of 2,055 brown recluse spiders (Araneae: Sicariidae) and no envenomations in a Kansas home: implications for bite diagnoses in nonendemic areas". Journal of Medical Entomology. 39 (6): 948–51. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-39.6.948. PMID 12495200.

- Hannum, C. & Miller, D.M. "Widow Spiders". Department of Entomology, Virginia Tech. Archived from the original on 2008-10-18. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- "Funnel web spiders". Australian Venom Research Unit. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- "Pub chef bitten by deadly spider". BBC. 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Diaz, J.H. (August 1, 2004). "The Global Epidemiology, Syndromic Classification, Management, and Prevention of Spider Bites". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 71 (2): 239–50. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2004.71.2.0700239. PMID 15306718.

- Williamson, J.A.; Fenner, P.J.; Burnett, J.W.; Rifkin, J. (1996). Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals: A Medical and Biological Handbook. UNSW Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-86840-279-6.

- Nishioka, S. de A. (2001). "Misdiagnosis of brown recluse spider bite". Western Journal of Medicine. 174 (4): 240. doi:10.1136/ewjm.174.4.240. PMC 1071344. PMID 11290673.

- Isbister, G.K. (2001). "Spider mythology across the world". Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (4): 86–87. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.2.86. PMC 1071491. PMID 11483545.

- Stuber, Marielle & Nentwig, Wolfgang (2016). "How informative are case studies of spider bites in the medical literature?". Toxicon. 114: 40–44. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.02.023. PMID 26923161.

- "Spider Venom Could Yield Eco-Friendly Insecticides". National Science Foundation (US). Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Salima Machkour M'Rabet; Yann Hénaut; Peter Winterton; Roberto Rojo (2011). "A case of zootherapy with the tarantula Brachypelma vagans Ausserer, 1875 in traditional medicine of the Chol Mayan ethnic group in Mexico". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 7: 12. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-7-12. PMC 3072308. PMID 21450096.

- Novak, K. (2001). "Spider venom helps hearts keep their rhythm". Nature Medicine. 7 (155): 155. doi:10.1038/84588. PMID 11175840.

- Lewis, R.J. & Garcia, M.L. (2003). "Therapeutic potential of venom peptides" (PDF). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2 (10): 790–802. doi:10.1038/nrd1197. PMID 14526382. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Bogin, O. (Spring 2005). "Venom Peptides and their Mimetics as Potential Drugs" (PDF). Modulator (19). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- Andrade, E.; Villanova, F.; Borra, P.; Leite, Katia; Troncone, Lanfranco; Cortez, Italo; Messina, Leonardo; Paranhos, Mario; et al. (2008). "Penile erection induced in vivo by a purified toxin from the Brazilian spider Phoneutria nigriventer". British Journal of Urology International. 102 (7): 835–37. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07762.x. PMID 18537953.

- Hinman, M.B.; Jones J.A.; Lewis, R. W. (2000). "Synthetic spider silk: a modular fiber" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. 18 (9): 374–79. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.682.313. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01481-5. PMID 10942961. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Menassa, R.; Zhu, H.; Karatzas, C.N.; Lazaris, A.; Richman, A.; Brandle, J. (2004). "Spider dragline silk proteins in transgenic tobacco leaves: accumulation and field production". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2 (5): 431–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00087.x. PMID 17168889.

- Ray, N. (2002). Lonely Planet Cambodia. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-74059-111-9.

- Weil, C. (2006). Fierce Food. Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-28700-6.

- "A Common Phobia". phobias-help.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

There are many common phobias, but surprisingly, the most common phobia is arachnophobia.

- Fritscher, Lisa (2009-06-03). "Spider Fears or Arachnophobia". Phobias. About.com. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

Arachnophobia, or fear of spiders, is one of the most common specific phobias.

- "The 10 Most Common Phobias – Did You Know?". 10 Most Common Phobias. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

Probably the most recognized of the 10 most common phobias, arachnophobia is the fear of spiders. The statistics clearly show that more than 50% of women and 10% of men show signs of this leader on the 10 most common phobias list.

- Friedenberg, J. & Silverman, G. (2005). Cognitive Science: An Introduction to the Study of Mind. SAGE. pp. 244–45. ISBN 978-1-4129-2568-6.

- Davey, G.C.L. (1994). "The "Disgusting" Spider: The Role of Disease and Illness in the Perpetuation of Fear of Spiders". Society and Animals. 2 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1163/156853094X00045.

- De Vos, Gail (1996). Tales, Rumors, and Gossip: Exploring Contemporary Folk Literature in Grades 7–12. Libraries Unlimited. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-56308-190-3.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. London, England: The British Museum Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1987). The Harps that Once: Sumerian Poetry in Translation. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norton, Elizabeth (2013). Aspects of Ecphrastic Technique in Ovid's Metamorphoses. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4438-4271-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harries, Byron (1990). "The spinner and the poet: Arachne in Ovid's Metamorphoses". The Cambridge Classical Journal. 36: 64–82. doi:10.1017/S006867350000523X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)