Springbok

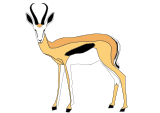

The springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in southern and southwestern Africa. The sole member of the genus Antidorcas, this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann in 1780. Three subspecies are identified. A slender, long-legged antelope, the springbok reaches 71 to 86 cm (28 to 34 in) at the shoulder and weighs between 27 and 42 kg (60 and 93 lb). Both sexes have a pair of black, 35-to-50 cm (14-to-20 in) long horns that curve backwards. The springbok is characterised by a white face, a dark stripe running from the eyes to the mouth, a light-brown coat marked by a reddish-brown stripe that runs from the upper fore leg to the buttocks across the flanks like the Thomson's gazelle, and a white rump flap.

| Springbok | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Male at Etosha National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Antilopinae |

| Tribe: | Antilopini |

| Genus: | Antidorcas Sundevall, 1847 |

| Species: | A. marsupialis |

| Binomial name | |

| Antidorcas marsupialis (Zimmermann, 1780) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

.png) | |

| Distribution map of springbok | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Active mainly at dawn and dusk, springbok form harems (mixed-sex herds). In earlier times, springbok of the Kalahari desert and Karoo migrated in large numbers across the countryside, a practice known as trekbokking. A feature, peculiar but not unique, to the springbok is pronking, in which the springbok performs multiple leaps into the air, up to 2 m (6.6 ft) above the ground, in a stiff-legged posture, with the back bowed and the white flap lifted. Primarily a browser, the springbok feeds on shrubs and succulents; this antelope can live without drinking water for years, meeting its requirements through eating succulent vegetation. Breeding takes place year-round, and peaks in the rainy season, when forage is most abundant. A single calf is born after a five- to six-month-long pregnancy; weaning occurs at nearly six months of age, and the calf leaves its mother a few months later.

Springbok inhabit the dry areas of south and southwestern Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the springbok as a least concern species. No major threats to the long-term survival of the species are known; the springbok, in fact, is one of the few antelope species considered to have an expanding population. They are popular game animals, and are valued for their meat and skin. The springbok is the national animal of South Africa.

Etymology

The common name "springbok" comes from the Afrikaans words spring ("jump") and bok ("antelope" or "goat");[2] the first recorded use of the name dates to 1775. The scientific name of the springbok is Antidorcas marsupialis; anti is Greek for "opposite", and dorcas for "gazelle" – identifying that the animal is not a gazelle. The specific epithet marsupialis comes from the Latin marsupium ("pocket"); it refers to a pocket-like skin flap which extends along the midline of the back from the tail.[3] In fact, this physical feature distinguishes the springbok from true gazelles.[4]

Taxonomy and evolution

The springbok is the sole member of the genus Antidorcas and is placed in the family Bovidae.[5] It was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann in 1780. Zimmermann assigned the genus Antilope (blackbuck) to the springbok.[6] In 1845, Swedish zoologist Carl Jakob Sundevall placed the springbok in Antidorcas, a genus of its own.[7]

In 2013, Eva Verena Bärmann (of the University of Cambridge) and colleagues undertook a revision of the phylogeny of the tribe Antilopini on the basis of nuclear and mitochondrial data. They showed that the springbok and the gerenuk (Litocranius walleri) form a clade with saiga (Saiga tatarica) as sister taxon.[8] The study pointed out that the saiga and the springbok could be considerably different from the rest of the antilopines; a 2007 phylogenetic study even suggested that the two form a clade sister to the gerenuk.[9] The cladogram below is based on the 2013 study.[8]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fossil springbok are known from the Pliocene; the antelope appears to have evolved about three million years ago from a gazelle-like ancestor. Three fossil species of Antidorcas have been identified, in addition to the extant form, and appear to have been widespread across Africa. Two of these, A. bondi and A. australis, became extinct around 7,000 years ago (early Holocene). The third species, A. recki, probably gave rise to the extant form A. marsupialis during the Pleistocene, about 100,000 years ago.[2][10] Fossils have been reported from Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene sites in northern, southern, and eastern Africa. Fossils dating back to 80 and 100 thousand years ago have been excavated at Herolds Bay Cave (Western Cape Province, South Africa) and Florisbad (Free State), respectively.[2]

Three subspecies are recognised:[2][11]

- A. m. angolensis (Blaine, 1922) – Occurs in Benguela and Moçâmedes (southwestern Angola).

- A. m. hofmeyri (Thomas, 1926) – Occurs in Berseba and Great Namaqualand (southwestern Africa). Its range lies north of the Orange River, stretching from Upington and Sandfontein through Botswana to Namibia.

- A. m. marsupialis (Zimmermann, 1780) – Its range lies south of the Orange River, extending from the northeastern Cape of Good Hope to the Free State and Kimberley.

Description

_juvenile_head_composite.jpg)

juvenile (left); sub-adult (right)

The springbok is a slender antelope with long legs and neck. Both sexes reach 71–86 cm (28–34 in) at the shoulder with a head-and-body length typically between 120 and 150 cm (47 and 59 in).[2] The weights for both sexes range between 27 and 42 kilograms (60 and 93 lb). The tail, 14 to 28 cm (5.5 to 11.0 in) long, ends in a short, black tuft.[2][12] Major differences in the size and weight of the subspecies are seen. A study tabulated average body measurements for the three subspecies. A. m. angolensis males stand 84 cm (33 in) tall at the shoulder, while females are 81 cm (32 in) tall. The males weigh around 31 kg (68 lb), while the females weigh 32 kg (71 lb). A. m. hofmeyri is the largest subspecies; males are nearly 86 cm (34 in) tall, and the notably shorter females are 71 cm (28 in) tall. The males, weighing 42 kg (93 lb), are heavier than females, that weigh 35 kg (77 lb). However, A. m. marsupialis is the smallest subspecies; males are 75 cm (30 in) tall and females 72 cm (28 in) tall. Average weight of males is 31 kg (68 lb), while for females it is 27 kg (60 lb).[2] Another study showed a strong correlation between the availability of winter dietary protein and the body mass.[13]

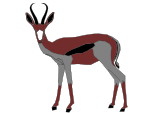

Dark stripes extend across the white face, from the corner of the eyes to the mouth. A dark patch marks the forehead. In juveniles, the stripes and the patch are light brown. The ears, narrow and pointed, measure 15–19 cm (5.9–7.5 in). Typically light brown, the springbok has a dark reddish-brown band running horizontally from the upper foreleg to the edge of the buttocks, separating the dark back from the white underbelly. The tail (except the terminal black tuft), buttocks, the insides of the legs and the rump are all white. Two other varieties – pure black and pure white forms – are artificially selected in some South African ranches.[14] Though born with a deep black sheen, adult black springbok are two shades of chocolate-brown and develop a white marking on the face as they mature. White springbok, as the name suggests, are predominantly white with a light tan stripe on the flanks.[2][14]

Typical springbok

Typical springbok Pure black springbok

Pure black springbok Pure white springbok

Pure white springbok

The three subspecies also differ in their colour. A. m. angolensis has a brown to tawny coat, with thick, dark brown stripes on the face extending two-thirds down to the snout. While the lateral stripe is nearly black, the stripe on the rump is dark brown. The medium brown forehead patch extends to eye level and is separated from the bright white face by a dark brown border. A brown spot is seen on the nose. A. m. hofmeyri is a light fawn, with thin, dark brown face stripes. The stripes on the flanks are dark brown to black, and the posterior stripes are moderately brown. The forehead patch, dark brown or fawn, extends beyond the level of the eyes and mixes with the white of the face without any clear barriers. The nose may have a pale smudge. A. m. marsupialis is a rich chestnut brown, with thin, light face stripes. The stripe near the rump is well-marked, and that on the flanks is deep brown. The forehead is brown, fawn, or white, the patch not extending beyond the eyes and having no sharp boundaries. The nose is white or marked with brown.[11]

The skin along the middle of the dorsal side is folded in, and covered with 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in) white hair erected by arrector pili muscles (located between hair follicles). This white hair is almost fully concealed by the surrounding brown hairs until the fold opens up, and this is a major feature distinguishing this antelope from gazelles.[2] Springbok differ from gazelles in several other ways; for instance, springbok have two premolars on both sides of either jaw, rather than the three observed in gazelles. This gives a total of 28 teeth in the springbok, rather than 32 of gazelles.[2] Other points of difference include a longer, broader, and rigid bridge to the nose and more muscular cheeks in springbok, and differences in the structure of the horns.[14]

Both sexes have black horns, about 35–50 cm (14–20 in) long, that are straight at the base and then curve backward. In A. m. marsupialis, females have thinner horns than males; the horns of females are only 60 to 70% as long as those of males. Horns have a girth of 71–83 mm (2.8–3.3 in) at the base; this thins to 56–65 mm (2.2–2.6 in) towards the tip. In the other two subspecies, horns of both sexes are nearly similar. The spoor, narrow and sharp, is 5.5 cm (2.2 in) long.[2]

Ecology and behaviour

_in_the_road.jpg)

Springbok are mainly active around dawn and dusk. Activity is influenced by weather; springbok can feed at night in hot weather, and at midday in colder months. They rest in the shade of trees or bushes, and often bed down in the open when weather is cooler.[15] The social structure of the springbok is similar to that of Thomson's gazelle. Mixed-sex herds or harems have a roughly 3:1 sex ratio; bachelor individuals are also observed.[16] In the mating season, males generally form herds and wander in search of mates. Females live with their offspring in herds, that very rarely include dominant males. Territorial males round up female herds that enter their territories and keep out the bachelors; mothers and juveniles may gather in nursery herds separate from harem and bachelor herds. After weaning, female juveniles stay with their mothers until the birth of their next calves, while males join bachelor groups.[14]

A study of vigilance behaviour of herds revealed that individuals on the borders of herds tend to be more cautious; vigilance decreases with group size. Group size and distance from roads and bushes were found to have major influence on vigilance, more among the grazing springbok than among their browsing counterparts. Adults were found to be more vigilant than juveniles, and males more vigilant than females. Springbok passing through bushes tend to be more vulnerable to predator attacks as they can not be easily alerted, and predators usually conceal themselves in bushes.[17] Another study calculated that the time spent in vigilance by springbok on the edges of herds is roughly double that spent by those in the centre and the open. Springbok were found to be more cautious in the late morning than at dawn or in the afternoon, and more at night than in the daytime. Rates and methods of vigilance were found to vary with the aim of lowering risk from predators.[18]

During the rut, males establish territories, ranging from 10 to 70 hectares (25 to 173 acres),[2] which they mark by urinating and depositing large piles of dung.[3] Males in neighbouring territories frequently fight for access to females, which they do by twisting and levering at each other with their horns, interspersed with stabbing attacks. Females roam the territories of different males. Outside of the rut, mixed-sex herds can range from as few as three to as many as 180 individuals, while all-male bachelor herds are of typically no more than 50 individuals. Harem and nursery herds are much smaller, typically including no more than 10 individuals.[2]

In earlier times, when large populations of springbok roamed the Kalahari desert and Karoo, millions of migrating springbok formed herds hundreds of kilometres long that could take several days to pass a town.[19] These mass treks, known as trekbokking in Afrikaans, took place during long periods of drought. Herds could efficiently retrace their paths to their territories after long migrations.[14] Trekbokking is still observed occasionally in Botswana, though on a much smaller scale than earlier.[20][21]

Springbok often go into bouts of repeated high leaps of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) into the air – a practice known as pronking (derived from the Afrikaans pronk, "to show off") or stotting.[2] In pronking, the springbok performs multiple leaps into the air in a stiff-legged posture, with the back bowed and the white flap lifted. When the male shows off his strength to attract a mate, or to ward off predators, he starts off in a stiff-legged trot, leaping into the air with an arched back every few paces and lifting the flap along his back. Lifting the flap causes the long white hairs under the tail to stand up in a conspicuous fan shape, which in turn emits a strong scent of sweat.[3] Although the exact cause of this behaviour is unknown, springbok exhibit this activity when they are nervous or otherwise excited. The most accepted theory for pronking is that it is a method to raise alarm against a potential predator or confuse it, or to get a better view of a concealed predator; it may also be used for display. Springbok are very fast antelopes, clocked at 88 km/h (55 mph). They generally tend to be ignored by carnivores unless they are breeding.[22] Caracals, cheetahs, leopards, spotted hyenas, lions and wild dogs are major predators of the springbok. Southern African wildcats, black-backed jackals, black eagles, martial eagles, and tawny eagles target juveniles.[2] Springbok are generally quiet animals, though they may make occasional low-pitched bellows as a greeting and high-pitched snorts when alarmed.[3]

Parasites

A 2012 study on the effects of rainfall patterns and parasite infections on the body of the springbok in Etosha National Park observed that males and juveniles were in better health toward the end of the rainy season. Health of females was more affected by parasites than by rainfall; parasite count in females peaked prior to and immediately after parturition.[23] Studies show that springbok host helminths (Haemonchus, Longistrongylus and Trichostrongylus), ixodid ticks (Rhipicephalus species), lice (Damalinia and Linognathus species).[24][25] Eimeria species mainly affect juveniles.[23]

Diet

Springbok are primarily browsers and may switch to grazing occasionally; they feed on shrubs and young succulents (such as Lampranthus species) before they lignify.[26] They prefer grasses such as Themeda triandra. Springbok can meet their water needs from the food they eat, and are able to survive without drinking water through dry season. In extreme cases, they do not drink any water over the course of their lives. Springbok may accomplish this by selecting flowers, seeds, and leaves of shrubs before dawn, when the food items are most succulent.[27] In places such as Etosha National Park, springbok seek out water bodies where they are available.[26] Springbok gather in the wet season and disperse during the dry season, unlike other African mammals.[26]

Reproduction

_suckling.jpg)

Springbok mate year-round, though females are more likely to enter oestrus during the rainy season, when food is more plentiful.[15] Females are able to conceive at as early as six to seven months, whereas males do not attain sexual maturity until two years;[4] rut lasts 5 to 21 days.[14] When a female approaches a rutting male, the male holds his head and tail at level with the ground, lowers his horns, and makes a loud grunting noise to attract her. The male then urinates and sniffs the female's perineum. If the female is receptive, she urinates, as well, and the male makes a flehmen gesture, and taps his leg till the female leaves or permits him to mate.[3][28] Copulation consists of a single pelvic thrust.[29]

Gestation lasts five to six months, after which a single calf (or rarely twins) is born.[15] Most births take place in the spring (October to November), prior to the onset of the rainy season.[14] The infant weighs 3.8 to 5 kg (8.4 to 11.0 lb); the female keeps her calf hidden in cover while she is away. Mother and calf rejoin the herd about three to four weeks after parturition; the young are weaned at five or six months. When the mother gives birth again, the previous offspring, now 6 to 12 months old, deserts her to join herds of adult springbok. Thus, a female can calve twice a year, and even thrice if one calf dies.[3][16] Springbok live for up to 10 years in the wild.[2]

Distribution and habitat

.jpg)

Springbok inhabit the dry areas of south and southwestern Africa. Their range extends from northwestern South Africa through the Kalahari desert into Namibia and Botswana. The Transvaal marks the eastern limit of the range, from where it extends westward to the Atlantic and northward to southern Angola and Botswana. In Botswana, they mostly occur in the Kalahari desert in the southwestern and central parts of the country. They are widespread across Namibia and the vast grasslands of the Free State and the shrublands of Karoo in South Africa; however, they are confined to the Namib Desert in Angola.[20]

The historic range of the springbok stretched across the dry grasslands, bushlands, and shrublands of south-western and southern Africa; springbok migrated sporadically in southern parts of the range. These migrations are rarely seen nowadays, but seasonal congregations can still be observed in preferred areas of short vegetation, such as the Kalahari desert.[26]

Threats and conservation

The springbok has been classified as least concern by the IUCN. No major threats to the long-term survival of the species are known. In fact, the springbok is one of the few antelope species with a positive population trend.[26][30]

Springbok occur in several protected areas across their range: Makgadikgadi and Nxai National Park (Botswana); Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park between Botswana and South Africa; Etosha National Park and Namib-Naukluft Park (Namibia); Mokala and Karoo National Parks and a number of provincial reserves in South Africa.[31] In 1999, Rod East of the IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group estimated the springbok population in South Africa at more than 670,000, noting that it might be an underestimate. However, estimates for Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Transvaal, Karoo, and the Free State (which gave a total population estimate of nearly 2,000,000 – 2,500,000 animals in southern Africa), were in complete disagreement with East's estimate. Springbok are under active management in several private lands. Small populations have been introduced into private lands and provincial areas of KwaZulu-Natal.[31][26]

Relationship with humans

Springbok are hunted as game throughout Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa because of their attractive coats; they are common hunting targets due to their large numbers and the ease with which they can be supported on farmlands. The export of springbok skins, mainly from Namibia and South Africa, is a booming industry; these skins serve as taxidermy models.[31] The meat is a prized fare, and is readily available in South African supermarkets.[32] As of 2011, the springbok, the gemsbok, and the greater kudu collectively account for around two-thirds of the game meat production from Namibian farmlands; nearly 90 tonnes (89 long tons; 99 short tons) of the springbok meat is exported as mechanically deboned meat to overseas markets.[33]

The latissimus dorsi muscle of the springbok comprises 1.1–1.3% ash, 1.3–3.5% fat, 72–75% moisture and 18–22% protein.[34] Stearic acid is the main fatty acid, accounting for 24–27% of the fatty acids. The cholesterol content varies from 54.5 to 59.0 milligrams (0.841 to 0.911 gr) per 100 grams (3.5 oz) of meat.[35] The pH of the meat increases if the springbok is under stress or cropping is done improperly; consequently, the quality deteriorates and the colour darkens.[36] The meat might be adversely affected if the animal is killed by shooting.[37] The meat may be consumed raw or used in prepared dishes. Biltong can be prepared by preserving the raw meat with vinegar, spices, and table salt, without fermentation, followed by drying. Springbok meat may also be used in preparing salami; a study found that the flavour of this salami is better than mutton salami, and feels oilier than salami of beef, horse meat, or mutton.[32]

The springbok has been a national symbol of South Africa since the white minority rule in the 20th century. It was adopted as a nickname or mascot by several South African sports teams, most famously by the national rugby union team. The springbok is the national animal of South Africa. Even after the decline of apartheid, Nelson Mandela intervened to keep the name of the animal for the reconciliation of rugby fans, the majority of whom were whites.[38][39] The springbok is featured on the reverse of the South African Krugerrand coin.[40][41]

The cap badge of The Royal Canadian Dragoons has featured a springbok since 1913, a reference to the unit's involvement in the Second Boer War.[42]

References

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2016). "Antidorcas marsupialis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T1676A115056763.

- Cain III, J.W.; Krausman, P.R.; Germaine, H.L. (2004). "Antidorcas marsupialis" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 753: 1–7. doi:10.1644/753. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2016.

- Bigalke, R.C. (1972). "Observations on the behaviour and feeding habits of the springbok Antidorcas marsupialis". Zoologica Africana. 7 (1): 333–59. doi:10.1080/00445096.1972.11447448.

- Rafferty, J.P. (2011). Grazers (1st ed.). New York, US: Britannica Educational Pub. pp. 103–4. ISBN 978-1-61530-465-3.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- von Zimmermann, E.A.W. (1780). Geographische Geschichte des Menschen, und der Allgemein Verbreiteten Vierfüssigen Thiere: Nebst Einer Hieher Gehörigen Zoologischen Weltcharte (in German). Leipzig, Germany: In der Weygandschen Buchhandlung. p. 427.

- Sundevall, C.J. (1844). "Melhodisk öfversigt af Idislande djuren, Linnés Pecora". Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar. 3 (in Swedish): 271.

- Bärmann, E.V.; Rössner, G.E.; Wörheide, G. (2013). "A revised phylogeny of Antilopini (Bovidae, Artiodactyla) using combined mitochondrial and nuclear genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 67 (2): 484–93. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.02.015. PMID 23485920.

- Marcot, J.D. (2007). "Molecular phylogeny of terrestrial artiodactyls". In Prothero, D.R.; Foss, S.E. (eds.). The Evolution of Artiodactyls (Illustrated ed.). Baltimore, US: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 4–18. ISBN 978-0-8018-8735-2.

- Vrba, E.S. (1973). "Two species of Antidorcas (Sundevall) at Swartkrans (Mammalia: Bovidae)". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 28 (15): 287–351.

- Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Baltimore, US: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 154–5. ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, US: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1202–3. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Robinson, T.J. (1979). "Influence of a nutritional parameter on the size differences of the three springbok subspecies". South African Journal of Zoology. 14 (1): 13–5. doi:10.1080/02541858.1979.11447642.

- Kingdon, J. (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (2nd ed.). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 571–2. ISBN 978-1-4729-1236-7.

- Skinner, J.D.; Louw, G.N. (1996). The Springbok Antidorcas marsupialis (Zimmerman 1780) (Transvaal Museum Monographs). 10. pp. 1–50. ISBN 978-0-907990-16-1.

- Bigalke, R.C. (1970). "Observations of springbok populations". Zoologica Africana. 5 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1080/00445096.1970.11447381.

- Burger, J.; Safina, C.; Gochfeld, M. (2000). "Factors affecting vigilance in springbok: importance of vegetative cover, location in herd, and herd size". Acta Ethologica. 2 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1007/s102119900013.

- Bednekoff, P.A.; Ritter, R. (1994). "Vigilance in Nxai Pan springbok, Antidorcas marsupialis". Behaviour. 129 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1163/156853994X00325.

- Haresnape, G. (1974). The Great Hunters. Purnell and Sons. ISBN 978-0-360-00232-6.

- Estes, R.D. (1999). The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals (Revised ed.). White River Junction, US: Chelsea Green Pub. Co. pp. 65–7. ISBN 978-0-907990-16-1.

- Child, G.; Le Riche, J.D. (1969). "Recent springbok treks (mass movements) in southwestern Botswana". Mammalia. 33 (3): 499–504. doi:10.1515/mamm.1969.33.3.499.

- Richard, W.; Milton, S.J.; Dean, J. (1999). The Karoo: Ecological Patterns and Processes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-521-12687-8.

- Turner, W.C.; Versfeld, W.D.; Kilian, J.W.; Getz, W.M. (2012). "Synergistic effects of seasonal rainfall, parasites, and demography on fluctuations in springbok body condition". Journal of Animal Ecology. 81 (1): 58–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01892.x. PMC 3217112. PMID 21831195.

- Horak, I.G.; Meltzer, D.G.A.; Vos, V.D. (1982). "Helminth and arthropod parasites of springbok, Antidorcas marsupialis, in the Transvaal and western Cape Province" (PDF). Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 49 (1): 7–10. PMID 7122069. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Horak, I.G.; Anthonissen, M.; Krecek, R.C.; Boomker, J. (1992). "Arthropod parasites of springbok, gemsbok, kudus, giraffes and Burchell's and Hartmann's zebras in the Etosha and Hardap Nature Reserves, Namibia" (PDF). Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 59 (4): 253–7. PMID 1297955.

- East, R.; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. Gland, Switzerland: The IUCN Species Survival Commission. pp. 263–4. ISBN 978-2-8317-0477-7.

- Nagy, K.A.; Knight, M.H. (1994). "Energy, water, and food use by springbok antelope (Antidorcas marsupialis) in the Kalahari Desert". Journal of Mammalogy. 75 (4): 860–72. doi:10.2307/1382468. JSTOR 1382468.

- David, J.H.M. (1978). "Observations on territorial behaviour of springbok, Antidorcas marsupialis, in the Bontebok National Park, Swellendam". Zoologica Africana. 13 (1): 123–41. doi:10.1080/00445096.1978.11447611. hdl:10499/AJ24053.

- Skinner, G. N. "The Springbok: Antidorcas marsupialis (Zimmermann, 1790). Ecology and physiology. Behaviour." Transvaal Museum Monographs 10.1 (1996).

- Doyle, A. (3 March 2009). "Quarter of antelopes under threat: report". Reuters. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). "Antidorcas marsupialis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Todorov, S.D.; Koep, K.S.C.; Van Reenen, C.A.; Hoffman, L.C.; Slinde, E.; Dicks, L.M.T. (2007). "Production of salami from beef, horse, mutton, Blesbok (Damaliscus dorcas phillipsi) and Springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) with bacteriocinogenic strains of Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus curvatus". Meat Science. 77 (3): 405–12. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.04.007. PMID 22061794.

- Magwedere, K.; Shilangale, R.; Mbulu, R.S.; Hemberger, Y.; Hoffman, L.C.; Dziva, F. (2013). "Microbiological quality and potential public health risks of export meat from springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) in Namibia". Meat Science. 93 (1): 73–8. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.08.007. PMID 22944735.

- Hoffman, L.C.; Kroucamp, M.; Manley, M. (2007). "Meat quality characteristics of springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis). 2: Chemical composition of springbok meat as influenced by age, gender and production region". Meat Science. 76 (4): 762–7. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.02.018. PMID 22061255.

- Hoffman, L.C.; Kroucamp, M.; Manley, M. (2007). "Meat quality characteristics of springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis). 3: Fatty acid composition as influenced by age, gender and production region". Meat Science. 76 (4): 768–73. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.02.019. PMID 22061256.

- Hoffman, LC.; Kroucamp, M.; Manley, M. (2007). "Meat quality characteristics of springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis). 1: Physical meat attributes as influenced by age, gender and production region". Meat Science. 76 (4): 755–61. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.02.017. PMID 22061254.

- von La Chevallerie, M.; van Zyl, J.H.M. (1971). "Some effects of shooting on losses of meat and meat quality in springbok and impala" (PDF). South African Journal of Animal Science. 1 (1): 113–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Ritter, C.R. (2012). South Africa. Minnesota, US: ABDO Publishing Company. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-61783-118-8.

- Evans, M.J. (2014). Broadcasting the End of Apartheid: Live Television and the Birth of the New South Africa. New York, US: I.B. Tauris. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-85773-583-6.

- Weston, R. (1983). Gold: A World Survey. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-203-09758-8.

- "New release silver and limited mintage gold coins from APMEX". CoinWeek. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Boer War". Dragoons.ca. The Royal Canadian Dragoons. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

External links

- . . 1914.

- "Springbuck". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Springbok". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Antidorcas marsupialis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 9 April 2016.