Etosha National Park

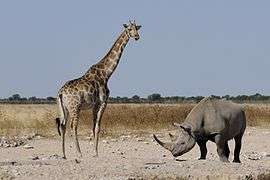

Etosha National Park is a national park in northwestern Namibia. It was proclaimed a game reserve in March 1907 in Ordinance 88 by the Governor of German South West Africa, Dr. Friedrich von Lindequist. It was designated as Wildschutzgebiet in 1958, and was elevated to the status of a national park in 1967 by an act of parliament of the Republic of South Africa.[1] It spans an area of 22,270 km2 (8,600 sq mi) and gets its name from the large Etosha pan which is almost entirely within the park. The Etosha pan (4,760 km2 (1,840 sq mi)) covers 23% of the total area of the National Park.[2] The park is home to hundreds of species of mammals, birds and reptiles, including several threatened and endangered species such as the black rhinoceros.

| Etosha National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

Animals at the Nebrownii waterhole | |

Map of show location in Namibia | |

| Location | Namibia |

| Coordinates | 18°56′43″S 15°53′52″E |

| Area | 22,270 km2 (8,600 sq mi) |

| Established | March 22, 1907 |

| Visitors | 200000 (in 2010) |

| Governing body | Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Namibia |

The park is located in the Kunene region and shares boundaries with the regions of Oshana, Oshikoto and Otjozondjupa.

History

Discovery by Europeans

Explorers Charles John Andersson and Francis Galton were the first Europeans to record the existence of the Etosha pan on 29 May 1851.[1] The explorers were traveling with Ovambo copper ore traders when they arrived at Omutjamatunda (now known as Namutoni). The Etosha pan was discovered when they traveled north upon leaving Namutoni. The name Etosha (spelled Etotha in early literature) comes from Oshindonga word meaning "Great White Place" referring to the Etosha pan. The Hai//om called the pan Khubus which means "totally bare, white place with lots of dust". The pan is also known as Chums, which refers to the noise made by a person's feet when walking on the clay of the pan.

People

Areas north of the Etosha pan were inhabited by Ovambo people, while various Otjiherero-speaking groups lived immediately outside the current park boundaries. The areas inside the park close to the Etosha pan had Khoisan-speaking Hai//om people.

When the Etosha pan was first discovered, the Hai//om people recognized the Ovambo chief at Ondonga but the Hereros did not.[3] The Hai||om were forcibly removed from the park in the 1954, ending their hunter-gatherer lifestyle to become landless farm laborers.[4] The Hai||om have had a recognized Traditional Authority since 2004 which helps facilitate communications between the community and the government. The government of Namibia acknowledges the park to be the home of Hai||om people and has plans to resettle displaced families on farms adjacent to the national park. Since 2007 the Government has acquired six farms directly south of the Gobaub depression in Etosha National Park. A number of families have settled on these farms under the leadership of Chief David Khamuxab, Paramount Chief of the Hai||om.

European settlers

In 1885, entrepreneur William Worthington Jordan bought a huge tract of land from Ovambo chief Kambonde. The land spanned nearly 170 kilometres (110 mi) from Okaukuejo in the west to Fischer's Pan in the east. The price for the land was £300 sterling, paid for by 25 firearms, one salted horse and a cask of brandy.[3] Dorstland Trekkers first traveled through the park between 1876 and 1879 on their way to Angola. The trekkers returned in 1885 and settled on 2,500-hectare (6,200-acre) farms given to them at no charge by Jordan. The trekkers named the area Upingtonia after the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. The settlement had to be abandoned in 1886 after clashes with the Hai||om[3] and defeat by Chief Nehale Mpingana.[5]

German South-West Africa

The German Reich ordered troops to occupy the Okaukuejo, Namutoni and Sesfontein in 1886 in order to kill migrating wildlife to stop spread of rinderpest to cattle. A fort was built by the German cavalry in 1889 at the site of the Namutoni spring. On 28 January 1904, 500 men under Nehale Mpingana attacked Imperial Germany's Schutztruppe at Fort Namutoni and completely destroyed it, driving out the colonial forces and taking over their horses and cattle.[5] The fort was rebuilt and troops stationed once again when the area was declared a game reserve in 1907; Lieutenant Adolf Fischer of Fort Namutoni then became its first "game warden".

Boundary

The present-day Etosha National Park has had many major and minor boundary changes since its inception in 1907. The major boundary changes since 1907 were because of Ordinance 18 of 1958 and Ordinance 21 of 1970.[1]

When the Etosha area was proclaimed as "Game Reserve 2" by Ordinance 88 of 1907, the park stretched from the mouths of the Kunene river and Hoarusib river on the Skeleton Coast to Namutoni in the east. The original area was estimated to be 99,526 square kilometres (38,427 sq mi), an estimate that has been corrected to about 80,000 square kilometres (31,000 sq mi).[1] Ordinance 18 of 1958 changed the western park boundaries to exclude the area between the Cunene river and the Hoarusib river and instead include the area between Hoanib river and Uchab river, thus reducing the park's area to 55,000 square kilometres (21,000 sq mi). The Odendaal Commission's (1963) decision resulted in the demarcation of the present-day park boundary in 1970.

Etosha Ecological Institute

The Etosha Ecological Institute was formally opened on 1 April 1974 by Adolf Brinkmann of the South-West African Administration.[1] The institute is responsible for all management-related research in the park. Classification of vegetation, population and ecological studies on wildebeest, elephants and lions, and studies on anthrax were among the first major topics to be investigated.[1] The EEI has collaborations with researchers from universities in Namibia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, South Africa, Australia, Norway and Israel.

Geography

Etosha Pan

The salt pans are the most noticeable geological features in the Etosha national park. The main depression covers an area of about 5,000 square kilometres (1,900 sq mi), and is roughly 130 km (81 mi) long and as wide as 50 km (31 mi) places. The hypersaline conditions of the pan limit the species that can permanently inhabit the pan itself; occurrences of extremophile micro-organisms are present, which species can tolerate the hypersaline conditions.[6] The salt pan is usually dry, but fills with water briefly in the summer, when it attracts pelicans and flamingos in particular. In the dry season, winds blowing across the salt pan pick up saline dust and carry it across the country and out over the southern Atlantic. This salt enrichment provides minerals to the soil downwind of the pan on which some wildlife depends, though the salinity also creates challenges to farming. The Etosha Pan was one of several sites throughout southern Africa in the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000). Using satellites, aircraft, and ground-based data from sites such as Etosha, partners in this program collected a wide variety of data on aerosols, land cover, and other characteristics of the land and atmosphere to study and understand the interactions between people and the natural environment.

Dolomite Hills

The dolomite hills on the southern border of the park near the Andersson entrance gate are called Ondundozonananandana, meaning the place where young boy herding cattle went to never return, probably implying a high density of predators like leopards in the hills, giving the mountains its English name of Leopard Hills.[1] The Halali area is also home to dolomite hills within the park, with one hill inside the camp and the nearby Twee Koppies. Western Etosha is also dominated by dolomite hills which is the only place in the park that has mountain zebra.

Climate

The national park of Etosha has a savanna desert climate. The annual mean average temperature is 24 °C (75 °F). In winter, the mean nighttime lows are around 10 °C (50 °F), while in summer temperatures often hover around 40 °C (104 °F). As it is a desert, there is a large variation between day and night. Rain almost never falls in the winter.

| Climate data for Etosha Safari Lodge, Namibia (2010–2017 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.2 (106.2) |

40.2 (104.4) |

38.3 (100.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

40.1 (104.2) |

41.2 (106.2) |

41.2 (106.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 34.3 (93.7) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

35.5 (95.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 129.5 (5.10) |

74.9 (2.95) |

78.2 (3.08) |

28.8 (1.13) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.01) |

2.1 (0.08) |

25.2 (0.99) |

79 (3.1) |

418 (16.5) |

| Source: [7] | |||||||||||||

Vegetation types

In most places in the park, the pans are devoid of vegetation with the exception of halophytic Sporobolus salsus, a protein-rich grass that is eaten by grazers like blue wildebeest and springbok. The areas around the Etosha pan also have other halophytic vegetation including grasses like Sporobolus spicatus and Odyssea paucinervis, as well as shrubs like Suaeda articulata. Most of the park is savanna woodlands except for areas close to the pan. Mopane is the most common tree, estimated to be around 80% of all trees in the park.[8] The sandveld of north-eastern corner of Etosha is dominated by acacia and Terminalia trees. Tamboti trees characterize the woodlands south of the sandveld. Dwarf shrub savanna occurs areas close to the pan and is home to several small shrubs including a halophytic succulent Salsola etoshensis. Thorn bush savanna occurs close to the pan on limestone and alkaline soils and is dominated by acacia species such as Acacia nebrownii, Acacia luederitzii, Acacia melliferra, Acacia hebeclada and Acacia tortilis. Grasslands in the park are mainly around the Etosha pan where the soil is sandy. Depending on the soil and the effects of the pan, grasslands could be dominated by one of the Eragrostis, Sporobolus, Monelytrum, Odyssea or Enneapogon species.

Fauna

The park has about 114 mammal species, 340 bird species, 110 reptile species, 16 amphibian species and 1 species of fish (up to 49 species of fish during floods).[9][10]

History

By 1881, large game mammals like elephants, rhinoceroses and lions had been nearly exterminated in the region.[1] The proclamation of the game reserve helped some of the animals recover, but some species like buffalo and wild dogs have been extinct since the middle of the 20th century. A writer from Otjiwarango was appointed game warden in 1951, and he considered the grasslands to be severely overgrazed. A bone meal plant was constructed near Rietfontein, and culling of zebras and wildebeests began in 1952. Official records indicate 293 zebras and 122 wildebeest were processed at the plant, but conservationists claimed thousands had been culled and successfully forced the plant's closure during the same year. The drought that began in the year 1980 resulted in the largest capture and culling operation in the history of the park.[1] 2235 mountain zebras and 450 plains zebras were captured, culled or sold. 525 elephants were culled and processed at a temporary abattoir near Olifantsrus.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered part of a Lion Conservation Unit.[11]

Mammals

Commonly seen mammals in the park, past and present, are listed in the table below

| Mammal | Status | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|

| African bush elephant | common | Etosha's elephants belong to the group of elephants in northwestern Namibia and southern Angola. They are the tallest elephants in Africa, but mineral deficiencies mean that they have very short tusks.[12] |

| Southern white rhinoceros | rare | Reintroduced recently after a long absence[13] |

| South-western black rhinoceros | not disclosed publicly | Odendaal Commission's plan in 1963 severely reduced the habitat of the rhinoceros as most of their preferred habitat fell outside the park.[14] Relocation programs have existed since then to increase the population of rhinos within the protected boundaries of the park. |

| Cape buffalo | extinct | The last known record of buffalo in the park is from an observation of a young bull killed by lions on the Andoni plains in the 1950s. |

| Angolan giraffe | common | A 2009 genetic study on this subspecies suggests that the northern Namib Desert and Etosha National Park populations form a separate subspecies.[15] |

| Lion | common | |

| Leopard | common | |

| Cheetah | uncommon | |

| Serval | rare | |

| Caracal | common | |

| Southern African wildcat | common | |

| Black-footed cat | very rare | |

| Black-backed jackal | very common | |

| Bat-eared fox | common | |

| Cape fox | common | |

| Cape wild dog | extinct | |

| Brown hyena | common | |

| Spotted hyena | common | |

| Aardwolf | common | |

| Meerkat | common | |

| Banded mongoose | common | |

| Yellow mongoose | common | |

| Slender mongoose | common | |

| Dwarf mongoose | uncommon | |

| Common genet | common | |

| Common warthog | common | |

| Scrub hare | common | |

| Springhare | common | |

| African ground squirrel | very common | |

| Honey badger | common | |

| Aardvark | common | |

| Crested porcupine | common | |

| Ground pangolin (Manis temminckii) | uncommon | |

| Plains zebra | very common | |

| Mountain zebra | locally common | Seen only in western Etosha |

| Springbok | very common | |

| Black-faced impala | common | |

| Gemsbok | common | |

| Common duiker | uncommon | |

| Damara dik-dik | common | |

| Steenbok | common | |

| Red hartebeest | common | |

| Blue wildebeest | common | |

| Common eland | uncommon | |

| Greater kudu | common |

.jpg)

Black rhinoceros with a giraffe

Black rhinoceros with a giraffe.jpg)

Greater kudu at Chudop waterhole

Greater kudu at Chudop waterhole Black-faced impala

Black-faced impala Lion at Gemsbokvlakte

Lion at Gemsbokvlakte African leopard near Okevi waterhole

African leopard near Okevi waterhole

Birds

This overview is only one indication of the diversity of birds in the park and is not a complete list.

|

Shrikes and Bushshrikes

Waxbills

|

Tourism

All lodging and camping accommodation inside the park is managed by Namibia Wildlife Resorts (NWR). There are five sites inside the park with lodges and four with facilities for camping. All sites have game-proof fences.[17]

Satellite picture of the park

Satellite picture of the park- Andersson Gate park entrance

Regulations in the park

Regulations in the park

Dolomite Camp

In the past, tourists were not allowed to go west of Ozonjuitji m'bari, and the only exception to that rule were registered Namibian tour operators and guests staying at Dolomite Camp. Dolomite Camp was built in 2010 and can be accessed from the Galton gate or through the park along the 19S latitude road (19e Breëdtegaard). Since 2015, the western part of Etosha is open to all tourists.

Halali

The Halali rest camp was opened in 1967 and is located about midway between Okaukuejo and Namutoni.

Namutoni

.jpg)

Namutoni is also a former police and military station in the eastern part of the park, 123 kilometres (76 mi) from Okaukuejo. Fort Namutoni was rebuilt in 1957 when it served as a rest camp for winter visitors to the park.

Okaukuejo

Okaukuejo was founded as a German South-West Africa military outpost in 1897 in an effort to control spread of foot-and-mouth disease. It later served as a police station and it was formally opened as a rest camp in 1955. The Okaukuejo tower was built in 1963 modeled after the old police station tower in the area. Okaukuejo has a restaurant, a post office, souvenir shops, two swimming pools and a tourist information center where visitors can record their daily observations. There is an observation deck at the Okaukuejo waterhole, which is floodlit at night for the benefit of tourists staying overnight, to observe nocturnal wildlife at the waterhole.

Onkoshi

Onkoshi is an exclusive property inside the park and is located near Stinkwater.

Olifantsrus

Olifantsrus Campsite is the newest camp to open inside the park. It is located between Okaukuejo and Dolomite. It does not have any accommodation in rooms or bungalows and offers a camping only experience. The main attraction here is glass fronted hide which overlooks a waterhole.

See also

References

- Berry, H. H. (1997). "Historical review of the Etosha Region and its subsequent administration as a National Park". Madoqua. 20 (1): 3–12. S2CID 131055181.

- Lindeque, M. and Archibald, T. J. (1991). "Seasonal wetlands in Owambo and the Etosha National Park". Madoqua. 17 (2): 129–133. S2CID 130968297.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Trümpelmann, G.P.J. 1948. Die Boer in Suid-wes Afrika.

- Born in Etosha. Ute Dieckmann (2009)

- "Namibia Heroes and Heroines". Namibia 1-on-1. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2010

- "Monthly reports / Etosha Safari (Reference period 2010−2018)". Etosha: Namibia Weather Network. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Trees and shrubs of the Etosha National Park and in northern and central Namibia; Cornelia Berry and Blythe Loutit

- Etosha Fact Sheet 2 Archived 2015-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Cunningham, P. L.; Jankowitz, W. "A Review of Fauna and Flora Associated with Coastal and Inland Saline Flats from Namibia with Special Reference to the Etosha Pan". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion Panthera leo in Eastern and Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: IUCN.

- Etosha Ecological Institute, Okaukuejo.

- Etosha Park Profile Archived January 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- On the clover trail. Eugène Joubert. 1996

- Brenneman, R. A.; Louis, E. E. Jr; Fennessy, J. (2009). "Genetic structure of two populations of the Namibian giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis". African Journal of Ecology. 47 (4): 720–28. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2009.01078.x.

- "The photographs of Etosha National Park, October 2017". Independent Travellers. independent-travellers.com. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Etosha National Park: Guidebook to the Waterholes and Animals. Timothy Osborne, Wilferd Versveld, Paul van Schalkwyk. 2003

- "Etosha National Park, Namibia". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 2003-12-05.

- C.Michael Hogan (2010), E. Monosson; C.Cleveland (eds.), Extremophile, Washington, D.C.: Encyclopedia of Earth, National Council for Science and the Environment, archived from the original on 2011-05-11

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Etosha National Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Etosha National Park. |