Indian rhinoceros

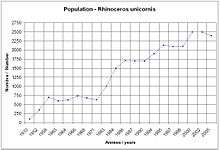

The Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), also called the greater one-horned rhinoceros and great Indian rhinoceros, is a rhinoceros species native to the Indian subcontinent. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, as populations are fragmented and restricted to less than 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi). Moreover, the extent and quality of the rhino's most important habitat, the alluvial Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands and riverine forest, is considered to be in decline due to human and livestock encroachment. As of 2008, a total of 2,575 mature individuals were estimated to live in the wild.[1]

| Indian rhinoceros | |

|---|---|

_4.jpg) | |

| An Indian rhinoceros near Narayani River in Nepal | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Rhinoceros |

| Species: | R. unicornis |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhinoceros unicornis | |

| |

| Indian rhinoceros range | |

The Indian rhinoceros once ranged throughout the entire stretch of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, but excessive hunting and agricultural development reduced its range drastically to 11 sites in northern India and southern Nepal. In the early 1990s, between 1,870 and 1,895 rhinos were estimated to have been alive.[2]

Taxonomy

Rhinoceros unicornis was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 who described a rhinoceros with one horn. As type locality, he indicated Africa and India.[3]

The one-horned rhinoceros is monotypic. Several specimens were described since the end of the 18th century under different scientific names, which are all considered synonyms of Rhinoceros unicornis today:[4]

- R. indicus by Cuvier, 1817

- R. asiaticus by Blumenbach, 1830

- R. stenocephalus by Gray, 1867

- R. jamrachi by Sclatter, 1876

- R. bengalensis by Kourist, 1970[5]

Etymology

The genus name Rhinoceros is a combination of the ancient Greek words ῥίς (ris) meaning 'nose' and κέρας (keras) meaning 'horn of an animal'.[6][7] The Latin word ūnicornis means one-horned.[8]

Evolution

Ancestral rhinoceroses first diverged from other perissodactyls in the Early Eocene. Mitochondrial DNA comparison suggests the ancestors of modern rhinos split from the ancestors of Equidae around 50 million years ago.[9] The extant family, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia, and the ancestors of the extant rhino species dispersed from Asia beginning in the Miocene.[10]

Fossils of R. unicornis appear in the Middle Pleistocene. In the Pleistocene, the genus Rhinoceros ranged throughout South and Southeast Asia, with specimens located on Sri Lanka. Into the Holocene, some rhinoceros lived as far west as Gujarat and Pakistan until as recently as 3,200 years ago.[11]

The Indian and Javan rhinoceroses, the only members of the genus Rhinoceros, first appear in the fossil record in Asia during the Early Pleistocene. The Indian Rhinoceros is known from Early Pleistocene localities in Java, South China, India and Pakistan.[12] Molecular estimates suggest the species may have diverged much earlier, around 11.7 million years ago.[9][13] Although belonging to the type genus, the Indian and Javan rhinoceroses are not believed to be closely related to other rhino species. Different studies have hypothesised that they may be closely related to the extinct Gaindatherium or Punjabitherium. A detailed cladistic analysis of the Rhinocerotidae placed Rhinoceros and the extinct Punjabitherium in a clade with Dicerorhinus, the Sumatran rhinoceros. Other studies have suggested the Sumatran rhinoceros is more closely related to the two African species.[14] The Sumatran rhino may have diverged from the other Asian rhinos as long as 15 million years ago.[10][15]

Characteristics

.jpg)

The Indian rhinoceros has a thick grey-brown skin with pinkish skin folds and one horn on its snout. Its upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps. It has very little body hair, aside from eyelashes, ear fringes and tail brush. Males have huge neck folds. Its skull is heavy with a basal length above 60 cm (24 in) and an occiput above 19 cm (7.5 in). Its nasal horn is slightly back-curved with a base of about 18.5 cm (7.3 in) by 12 cm (4.7 in) that rapidly narrows until a smooth, even stem part begins about 55 mm (2.2 in) above base. In captive animals, the horn is frequently worn down to a thick knob.[11]

The rhino's single horn is present in both males and females, but not on newborn calves. The horn is pure keratin, like human fingernails, and starts to show after about six years. In most adults, the horn reaches a length of about 25 cm (9.8 in), but has been recorded up to 36 cm (14 in) in length and weight 3.051 kg (6.73 lb).[15]

Among terrestrial land mammals native to Asia, the Indian rhinoceros is second in size only to the Asian elephant. It is also the second-largest living rhinoceros, behind only the white rhinoceros. Males have a head and body length of 368–380 cm (12.07–12.47 ft) with a shoulder height of 170–186 cm (5.58–6.10 ft), while females have a head and body length of 310–340 cm (10.2–11.2 ft) and a shoulder height of 148–173 cm (4.86–5.68 ft).[16] The male, averaging about 2,200 kg (4,850 lb) is heavier than the female, at an average of about 1,600 kg (3,530 lb).[16]

The rich presence of blood vessels underneath the tissues in folds gives it the pinkish colour. The folds in the skin increase the surface area and help in regulating the body temperature.[17] The thick skin does not protect against bloodsucking Tabanus flies, leeches and ticks.[11]

The largest sized specimens range up to 4,000 kg (8,820 lb).[18]

Distribution and habitat

The Indian rhinoceros once ranged across the entire northern part of the Indian Subcontinent, along the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra River basins, from Pakistan to the Indian-Myanmar border, including Bangladesh and the southern parts of Nepal and Bhutan. It may have also occurred in Myanmar, southern China and Indochina. It inhabits the alluvial grasslands of the Terai and the Brahmaputra basin.[2] As a result of habitat destruction and climatic changes its range has gradually been reduced so that by the 19th century, it only survived in the Terai grasslands of southern Nepal, northern Uttar Pradesh, northern Bihar, northern West Bengal, and in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam.[19]

The species was present in northern Bihar and Oudh at least until 1770 as indicated in maps produced by Colonel Gentil.[20] On the former abundance of the species, Thomas C. Jerdon wrote in 1867:[21]

This huge rhinoceros is found in the Terai at the foot of the Himalayas, from Bhutan to Nepal. It is more common in the eastern portion of the Terai than the west, and is most abundant in Assam and the Bhutan Dooars. I have heard from sportsmen of its occurrence as far west as Rohilcund, but it is certainly rare there now, and indeed along the greater part of the Nepal Terai; ... Jelpigoree, a small military station near the Teesta River, was a favourite locality whence to hunt the Rhinoceros and it was from that station Captain Fortescue ... got his skulls, which were ... the first that Mr. Blyth had seen of this species, ...

Today, its range has further shrunk to a few pockets in southern Nepal, northern West Bengal, and the Brahmaputra Valley. In the 1980s, rhinos were frequently seen in the narrow plain area of Royal Manas National Park in Bhutan. Today, they are restricted to habitats surrounded by human-dominated landscapes, so that they often occur in adjacent cultivated areas, pastures, and secondary forests.[19]

The Indian rhinoceros is regionally extinct in Pakistan.[22]

Populations

In 2006, the total population was estimated to be 2,575 individuals, of which 2,200 lived in Indian protected areas:[23]

- in Kaziranga National Park: 1,855 — increased from 366 in 1966; 2,048 rhinos were estimated in 2009.[24]

- in Jaldapara National Park: 108 — increased from 84 in 2002

- in Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary: 81 — increased from 54 in 1987

- in Orang National Park: 68 — increased from 35 in 1972

- in Gorumara: 27 — increased from 22 in 2002

- in Dudhwa National Park: 21

- in Manas National Park: 19

- in Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary: 2

In 2000, about 2,000 rhinos were estimated in Assam. Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary shelters the highest density of Indian rhinos in the world — with 84 individuals in 2009 in an area of 38.80 km2 (14.98 sq mi).[25] By 2014, the population in Assam increased to 2,544 rhinos, an increase by 27% since 2006, although more than 150 individuals were killed by poachers during these years.[26]

The population in Nepal increased by 111 individuals from 2011 to 2015, increasing by 21%. The latest rhino count was conducted from 11 April to 2 May 2015 and revealed 645 individuals living in Parsa National Park, Chitwan National Park, Bardia National Park, Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve and respective buffer zones in the Terai Arc Landscape.[27]

In Pakistan's Lal Suhanra National Park, two rhinos from Nepal were introduced in 1983 but have not bred so far.[1]

Ecology and behaviour

Adult males are usually solitary. Groups consist of females with calves, or of up to six subadults. Such groups congregate at wallows and grazing areas. They are foremost active in early mornings, late afternoons and at night, but rest during hot days.[11] They bathe regularly. The folds in their skin trap water and hold it even when they exit wallows.[17]

They are excellent swimmers and can run at speeds of up to 55 km/h (34 mph) for short periods. They have excellent senses of hearing and smell, but relatively poor eyesight. Over 10 distinct vocalisations have been recorded. Males have home ranges of around 2 to 8 km2 (0.77 to 3.09 sq mi) that overlap each other. Dominant males tolerate other males passing through their territories except when they are in mating season, when dangerous fights break out. Indian rhinos have few natural enemies, except for tigers, which sometimes kill unguarded calves, but adult rhinos are less vulnerable due to their size. Mynahs and egrets both eat invertebrates from the rhino's skin and around its feet. Tabanus flies, a type of horse-fly, are known to bite rhinos. The rhinos are also vulnerable to diseases spread by parasites such as leeches, ticks, and nematodes. Anthrax and the blood-disease sepsis are known to occur.[11] In March 2017, of a group of four tigers consisting of an adult male, tigress and two cubs killed a 20-year-old male Indian rhinoceros in Dudhwa Tiger Reserve.[28]

Diet

Indian rhinoceros are grazers. Their diet consists almost entirely of grasses, but they also eat leaves, branches of shrubs and trees, fruits, and submerged and floating aquatic plants. They feed in the mornings and evenings. They use their semi-prehensile lips to grasp grass stems, bend the stem down, bite off the top, and then eat the grass. They tackle very tall grasses or saplings by walking over the plant, with legs on both sides and using the weight of their bodies to push the end of the plant down to the level of the mouth. Mothers also use this technique to make food edible for their calves. They drink for a minute or two at a time, often imbibing water filled with rhinoceros urine.[11]

Social life

The Indian rhinoceros forms a variety of social groupings. Males are generally solitary, except for mating and fighting. Females are largely solitary when they are without calves. Mothers will stay close to their calves for up to four years after their birth, sometimes allowing an older calf to continue to accompany her once a newborn calf arrives. Subadult males and females form consistent groupings, as well. Groups of two or three young males will often form on the edge of the home ranges of dominant males, presumably for protection in numbers. Young females are slightly less social than the males. Indian rhinos also form short-term groupings, particularly at forest wallows during the monsoon season and in grasslands during March and April. Groups of up to 10 rhinos may gather in wallows—typically a dominant male with females and calves, but no subadult males.[15]

The Indian rhinoceros makes a wide variety of vocalisations. At least 10 distinct vocalisations have been identified: snorting, honking, bleating, roaring, squeak-panting, moo-grunting, shrieking, groaning, rumbling and humphing. In addition to noises, the rhino uses olfactory communication. Adult males urinate backwards, as far as 3–4 m behind them, often in response to being disturbed by observers. Like all rhinos, the Indian rhinoceros often defecates near other large dung piles. The Indian rhino has pedal scent glands which are used to mark their presence at these rhino latrines. Males have been observed walking with their heads to the ground as if sniffing, presumably following the scent of females.[15] In aggregations, Indian rhinos are often friendly. They will often greet each other by waving or bobbing their heads, mounting flanks, nuzzling noses, or licking. Rhinos will playfully spar, run around, and play with twigs in their mouths. Adult males are the primary instigators in fights. Fights between dominant males are the most common cause of rhino mortality, and males are also very aggressive toward females during courtship. Males will chase females over long distances and even attack them face-to-face. Unlike African rhinos, the Indian rhino fights with its incisors, rather than its horns.[15]

Reproduction

Captive males breed at five years of age, but wild males attain dominance much later when they are larger. In one five-year field study, only one rhino estimated to be younger than 15 years mated successfully. Captive females breed as young as four years of age, but in the wild, they usually start breeding only when six years old, which likely indicates they need to be large enough to avoid being killed by aggressive males. Their gestation period is around 15.7 months, and birth interval ranges from 34–51 months.[15]

In captivity, four rhinos are known to have lived over 40 years, the oldest living to be 47.[11]

Threats

Sport hunting became common in the late 1800s and early 1900s.[1] Indian rhinos were hunted relentlessly and persistently. Reports from the middle of the 19th century claim that some British military officers in Assam individually shot more than 200 rhinos. By 1908, the population in Kaziranga had decreased to around 12 individuals.[11] In the early 1900s, the species had declined to near extinction.[1]

Poaching for rhinoceros horn became the single most important reason for the decline of the Indian rhino after conservation measures were put in place from the beginning of the 20th century, when legal hunting ended. From 1980 to 1993, 692 rhinos were poached in India. In India's Laokhowa Wildlife Sanctuary, 41 rhinos were killed in 1983, virtually the entire population of the sanctuary.[29] By the mid-1990s, poaching had rendered the species extinct there.[2]

In 1950, Chitwan’s forest and grasslands extended over more than 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi) and were home to about 800 rhinos. When poor farmers from the mid-hills moved to the Chitwan Valley in search of arable land, the area was subsequently opened for settlement, and poaching of wildlife became rampant. The Chitwan population has repeatedly been jeopardised by poaching; in 2002 alone, poachers killed 37 animals to saw off and sell their valuable horns.[30]

Six methods of killing rhinos have been recorded:[29]

- Shooting is by far the most common method used; rhino horn traders hire sharpshooters and often supply them with rifles and ammunition.

- Trapping in a pit depends largely on the terrain and availability of grass to cover it; pits are dug out in such a way that a fallen animal has little room to manoeuvre with its head slightly above the pit, so that it is easy to saw off the horn.

- Electrocution is used where high voltage powerlines pass through or near a protected area, to which poachers hook a long, insulated rod connected to a wire, which is suspended above a rhino path.

- Poisoning by smearing zinc phosphide rat poison or pesticides on salt licks frequently used by rhinos is sometimes used.

- Spearing has only been recorded in Chitwan National Park.

- A noose, which cuts through the rhino's skin, kills it by strangulation.

Poaching, mainly for the use of the horn in traditional Chinese medicine, has remained a constant and has led to decreases in several important populations. Apart from this, serious declines in quality of habitat have occurred in some areas, due to:

- severe invasion by alien plants into grasslands affecting some populations;

- demonstrated reductions in the extent of grasslands and wetland habitats due to woodland encroachment and silting up of beels;

- grazing by domestic livestock.[1]

The species is inherently at risk because over 70% of its population occurs at a single site, Kaziranga National Park. Any catastrophic event such as disease, civil disorder, poaching, or habitat loss would have a devastating impact on the Indian rhino's status. However, small population of rhinos may be prone to inbreeding depression.[1]

Conservation

Rhinoceros unicornis has been listed in CITES Appendix I since 1975. The Indian and Nepalese governments have taken major steps towards Indian rhinoceros conservation, especially with the help of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and other non-governmental organisations.[1] In the early 1980s, a rhino translocation scheme was initiated. The first pair of rhinos was reintroduced from Nepal's Terai to Pakistan's Lal Suhanra National Park in Punjab in 1982.[19]

In India

In 1910, all rhino hunting in India became prohibited.[11] In 1984, five rhinos were relocated to Dudhwa National Park — four from the fields outside the Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary and one from Goalpara.[19]

In Nepal

In 1957, the country's first conservation law ensured the protection of rhinos and their habitat. In 1959, Edward Pritchard Gee undertook a survey of the Chitwan Valley, and recommended the creation of a protected area north of the Rapti River and of a wildlife sanctuary south of the river for a trial period of 10 years.[31] After his subsequent survey of Chitwan in 1963, he recommended extension of the sanctuary to the south.[32] By the end of the 1960s, only 95 rhinos remained in the Chitwan Valley. The dramatic decline of the rhino population and the extent of poaching prompted the government to institute the Gaida Gasti – a rhino reconnaissance patrol of 130 armed men and a network of guard posts all over Chitwan. To prevent the extinction of rhinos, the Chitwan National Park was gazetted in December 1970, with borders delineated the following year and established in 1973, initially encompassing an area of 544 km2 (210 sq mi). To ensure the survival of rhinos in case of epidemics, animals were translocated annually from Chitwan to Bardia National Park and Shuklaphanta National Park since 1986.[30] The Indian rhinoceros population living in Chitwan and Parsa National Parks was estimated at 608 mature individuals in 2015.[33]

In captivity

The Indian rhinoceros was initially difficult to breed in captivity. The first recorded captive birth of a rhinoceros was in Kathmandu in 1826, but another successful birth did not occur for nearly 100 years. In 1925, a rhino was born in Kolkata. No rhinoceros was successfully bred in Europe until 1956. On September 14, 1956, Rudra was born in Zoo Basel, Switzerland. In the second half of the 20th century, zoos became adept at breeding Indian rhinoceros. By 1983, nearly 40 babies had been born in captivity.[11] As of 2012, 33 Indian rhinos were born at Zoo Basel alone,[34] meaning that most captive animals are related to the Basel population. Due to the success of Zoo Basel's breeding program, the International Studbook for the species has been kept there since 1972. Since 1990, the Indian rhino European Endangered Species Programme is also being coordinated there, with the goal of maintaining genetic diversity in the global captive Indian rhinoceros population.[35] As of 2010, 174 rhinos are kept in zoos worldwide.

In June 2009, an Indian rhino was artificially inseminated using sperm collected four years previously and cryopreserved at the Cincinnati Zoo’s CryoBioBank before being thawed and used. She gave birth to a male calf in October 2010.[36] The calf died 12 hours after birth.

In June 2014, the first "successful" live-birth from an artificially inseminated rhino took place at the Buffalo Zoo in New York. As in Cincinnati, cryopreserved sperm was used to produce the female calf, Monica.[37]

In culture

The Rhinoceros Sutra is an early text in the Buddhist tradition, found in the Gandhāran Buddhist texts and the Pali Canon, as well as a version incorporated into the Sanskrit Mahavastu.[38] It praises the solitary lifestyle and stoicism of the Indian rhinoceros and is associated with the eremetic lifestyle symbolized by the Pratyekabuddha.[39]

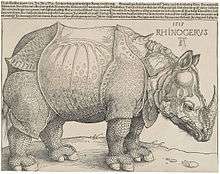

In the 3rd century, Philip the Arab exhibited an Indian rhinoceros in Rome. In 1515, Manuel I of Portugal obtained an Indian rhinoceros as a gift, which he passed on to Pope Leo X, but which died on the way from Lisboa to Rome. Three artistic representations were prepared of this rhinoceros: a woodcut by Hans Burgkmair dated to 1515, a drawing and a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer, also dated 1515. Latter is known as 'Dürer's Rhinoceros'. In about 1684, the first presumably Indian rhinoceros arrived in England.[40] George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys spread the rumour that his chief rival Francis North, 1st Baron Guilford had been seen riding on it.[41] In 1739, a rhinoceros exhibited in London was drawn and engraved by two English artists. It was then brought to Amsterdam, where Jan Wandelaar made two engravings that were published in 1747. In the subsequent years, the rhinoceros was exhibited in several European cities. In 1748, Johann Elias Ridinger made an etching of it in Augsburg, and Petrus Camper modelled it in clay in Leiden. In 1749, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon drew it in Paris. In 1751, Pietro Longhi painted it in Venice.[40]

A steatite seal, popularly known as Pashupati Seal (around 2350–2000 BC) was discovered at the Mohenjo-daro archaeological site in 1928–1929 of the Indus Valley Civilisation. It has a human figure at the centre seated on a platform and the human figure is surrounded by four wild animals: an elephant and a tiger to its one side, and a water buffalo and a rhinoceros on the other. Rhinoceros is Vahana of the Hindu goddess Dhavdi. There is a temple dedicated to Maa (Mother) Dhavdi in Dhrangadhra, Gujarat.

In China's classic novel Journey to the West, three Indian Rhinoceros demons, King of Cold Protection (辟寒大王), King of Heat Protection (辟暑大王) and King of Dust Protection (辟塵大王) were based in Xuanying Cave (玄英洞), Azure Dragon Mountain (青龍山) in Jinping Prefecture (金平府). They disguise themselves as Taoist deities and steal aromatic oil from lamps in a temple, tricking worshippers into believing that the "deities" have accepted the oil offered to them.

Many the mythological stories e.g. a boy named Rishyasringa with the horns of a deer, Karkadann, unicorn may be inspired by Indian rhinoceros.

See also

References

- Ellis, S. & Talukdar, B. (2019). "Rhinoceros unicornis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T19496A18494149. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Foose, T. & van Strien, N. (1997). Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- Linnæus, C. (1758). "Rhinoceros unicornis". Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Holmiae: Salvius. p. 56.

- Srinivasulu, C., Srinivasulu, B. (2012). Chapter 3: Checklist of South Asian Mammals in: South Asian Mammals: Their Diversity, Distribution, and Status. Springer, New York, Heidelberg, London.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "ῥίς". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "κέρᾳ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Partridge, E. (1983). "ūnicornis". Origins: a Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Greenwich House. p. 296. ISBN 0-517-41425-2.

- Xu, X.; Janke, A. & Arnason, U. (1996). "The Complete Mitochondrial DNA Sequence of the Greater Indian Rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis, and the Phylogenetic Relationship Among Carnivora, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla (+ Cetacea)". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 13 (9): 1167–1173. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025681. PMID 8896369.

- Lacombat, F. (2005). "The evolution of the rhinoceros" (PDF). In Fulconis, R. (ed.). Save the Rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. pp. 46–49.

- Laurie, W. A.; Lang, E. M.; Groves, C. P. (1983). "Rhinoceros unicornis" (PDF). Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists (211): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504002. JSTOR 3504002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-29.

- Antoine, P.-O. (2012). "Pleistocene and Holocene rhinocerotids (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Indochinese Peninsula". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (2–3): 159–168. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.03.002.

- Tougard, C.; Delefosse, T.; Hoenni, C. & Montgelard, C. (2001). "Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 19 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0903. PMID 11286489.

- Cerdeño, E. (1995). "Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)" (PDF). Novitates. American Museum of Natural History (3143): 1–25. ISSN 0003-0082.

- Dinerstein, E. (2003). The Return of the Unicorns: The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0198508239.

- Attenborough, D. (2014). Attenborough's Natural Curiosities 2. Armoured Animals. UKTV.

- Boitani, L. (1984). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster, Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1.

- Choudhury, A. U. (1985). "Distribution of Indian one-horned rhinoceros". Tiger Paper. 12 (2): 25–30.

- Rookmaaker, K. (2014). "Three rhinos on maps of India drawn in Faizabad in the 18th century". Pachyderm (55): 95–96.

- Jerdon, T. C. (1867). The Mammals of India: a Natural History of all the animals known to inhabit Continental India. Roorkee: Thomason College Press.

- Sheikh, K. M., Molur, S. (2004). Status and Red List of Pakistan's Mammals. Based on the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (PDF). IUCN Pakistan.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Syangden, B.; Sectionov; Ellis, S.; Williams, A.C.; Strien, N.J. van; Talukdar, B.K. (2008). Report on the regional meeting for India and Nepal IUCN/SSC Asian Rhino Species Group (AsRSG); March 5–7, 2007 Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India. Kaziranga, Asian Rhino Specialist Group.

- Medhi, A., Saha, A. K. (2014). Land Cover Change and Rhino Habitat Mapping of Kaziranga National Park, Assam. In: Singh, M. Singh, R. B., Hassan, M. I. (eds.) Climate Change and Biodiversity. Proceedings of IGU Rohtak Conference, Vol. 1, Part II. Springer Japan.Pp. 125–138.

- Sarma, P. K., Talukdar, B. K., Sarma, K., Barua, M. (2009). Assessment of habitat change and threats to the greater one-horned rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Pabitora Wildlife Sanctuary, Assam, using multi-temporal satellite data. Pachyderm No. 46 July–December 2009: 18–24.

- Hance, J. (June 2014). "Despite poaching, Indian rhino population jumps by 27 percent in eight years". Mongabay.com.

- WWF Nepal (2015-05-05). Nepal achieves 21% increase in rhino numbers.

- Tigers kill rhino in Dudhwa Tiger Reserve. Tribune India (4 March 2017)

- Menon, V. (1996) Under siege: Poaching and protection of Greater One-horned Rhinoceroses in India. TRAFFIC India

- Adhikari, T. R. (2002) The curse of success. Habitat Himalaya – A Resources Himalaya Factfile, Volume IX, Number 3

- Gee, E. P. (1959). "Report on a survey of the rhinoceros area of Nepal". Oryx. 5 (2): 67–76. doi:10.1017/S0030605300000326.

- Gee, E. P. (1963). "Report on a brief survey of the wildlife resources of Nepal, including rhinoceros". Oryx. 7 (2–3): 67–76. doi:10.1017/S0030605300002416.

- Pant, G.; Maraseni, T.; Apan, A. & Allen, B.L. (2020). "Climate change vulnerability of Asia's most iconic megaherbivore: greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis)". Global Ecology and Conservation. 23: e01180. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01180.

- (in German) Es ist ein Junge!. Zoo Basel, retrieved 2013-02-25

- Panzernashorngeburt im Zoo Basel. Zoo Basel. 27 July 2010

- Patton, F. (2011) The Artificial Way. Swara, (April–June 2011): 58–61.

- Miller, M. (2014) Baby Rhinoceros Makes Her Public Debut at Buffalo Zoo. The Buffalo News, (7 July 2014)

- Salomon, R. (1997). "A Preliminary Survey of Some Early Buddhist Manuscripts Recently Acquired by the British Library". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 117 (2): 353–358. doi:10.2307/605500. JSTOR 605500.

- Von Hinuber, O. (2003). "Review: A Gandhari Version of the Rhinoceros Sutra". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (1): 221–224. JSTOR 3217869.

- Rookmaaker, L. C. (1973). "Captive rhinoceroses in Europe from 1500 until 1810" (PDF). Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 43 (1): 39–63. doi:10.1163/26660644-04301002.

- Society for Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1841). "Rhinoceros". The Penny Cyclopaedia. Volume 19. London: Charles Knight & Co. pp. 463–475.

Further reading

Martin, E. B. (2010). From the jungle to Kathmandu : horn and tusk trade. Kathmandu: Wildlife Watch Group. ISBN 978-99946-820-9-6.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Rhinoceros unicornis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhinoceros unicornis. |

- "Rhino Resource Center".

- {{cite web |title=Greater One-Horned Rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) |website=International Rhino Foundation

- "Great Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis)". ECOS Environmental Conservation Online System.

- Nepal Rhino Conservation

- TheBigZoo.com: Greater Indian Rhinoceros

- Indian Rhino page at AnimalInfo.org

- Indian Rhinoceros page at nature.ca

- Indian Rhinoceros page at UltimateUngulate.com

- "Rhino census in India's Kaziranga park counts 12 more". BBC News. 2018.

- "Indian Rhinoceros". Arkive. Archived from the original on 2007-12-17.