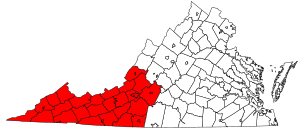

Southwest Virginia

Southwest Virginia, often abbreviated as SWVA, is a mountainous region of Virginia in the westernmost part of the commonwealth. Located within the broader region of western Virginia, Southwest Virginia has been defined alternatively as all Virginia counties on the Appalachian Plateau, all Virginia counties west of the Eastern Continental Divide, or at its greatest expanse, as far east as Blacksburg and Roanoke. Another geographic categorization of the region places it as those counties within the Tennessee River watershed. Regardless of how borders are drawn, Southwest Virginia differs from the rest of the commonwealth in that its culture is more closely associated with Appalachia than the other regions of Virginia. Historically, the region has been and remains a rural area, but in the 20th century, coal mining became an important part of its economy. With the decline in the number of coal jobs and the decline of tobacco as a cash crop, Southwest Virginia is increasingly turning to tourism as a source of economic development. Collectively, Southwest Virginia's craft, music, agritourism and outdoor recreation are referred to as the region's "creative economy."[1]

Counties that have been included in the definition of Southwest Virginia include: Alleghany County, Bedford County, Bland County, Botetourt County, Buchanan County, Carroll County, Craig County, Dickenson County, Floyd County, Franklin County, Giles County, Grayson County, Henry County, Lee County, Montgomery County, Patrick County, Pulaski County, Roanoke County, Rockbridge County, Russell County, Scott County, Smyth County, Tazewell County, Washington County, Wise County, and Wythe County.

Unlike other states in the U.S., Virginia draws a sharp distinction between cities and other incorporated communities, all of which are designated as towns. Under state law, all municipalities incorporated as cities are independent of any county. By contrast, places incorporated as towns are included within counties. Independent cities in Southwest Virginia include Bristol, Buena Vista, Covington, Galax, Lexington, Martinsville, Norton, Radford, Roanoke, and Salem.

Culture

The culture of Southwest Virginia is more consistent with the wider Appalachian region than with the rest of the state of Virginia. This is due in large part to the geographical diversity of the state, with the Appalachian and Blue Ridge mountains dominating the region. Recently, the region is becoming known for its music, craft and outdoor recreation opportunities.

The center of Southwest Virginia's creative economy movement is Heartwood, a regional visitors' center with a restaurant and craft galleries located off of Interstate 81 in the town of Abingdon. This $17 million facility, built through a collaborative state and regional partnership, opened in 2011 and serves as the hub of regional networks and driving trails that cater to visitors. Additionally, Round the Mountain has established 15 driving trails in different parts of the region that link artisan and agricultural destinations along with local lodging and dining experiences. Such destinations are being developed by an initiative called Appalachian Spring, which is working with communities in the region to link together recreation destinations.

Southwest Virginia boasts a robust musical heritage, particularly in blues, folk, and bluegrass, which has been promoted since 2002 through a driving trail called The Crooked Road. The east-west driving route of more than 300 miles links together a variety of music performance venues and destinations in the region.

History

Southwest Virginia was among the last parts of the state to be settled by Europeans, in a flow of migrations that consisted mainly of English, German, and Scots-Irish and Irish immigrants. A major route of migration to the region was the Great Wagon Road through the Great Appalachian Valley. At present-day Roanoke there was an important fork in the wagon road, with one branch passing through the Blue Ridge and into the Piedmont region, and the other branch, called the Wilderness Road, continuing southwest to Tennessee and Kentucky. Much of the area was protected by a series of forts constructed around the time of Lord Dunmore's War, some of which later became the seats of future counties.

The first major industry in Southwest Virginia — which laid the foundation for the regionally important town of Abingdon — was salt. In Saltville (a small town now located on the Smyth-Washington county line), salt was (and still is) produced by using water to extract salt from the ground. The salt marshes in this unique area are also known for woolly mammoth finds, and as a result the town has adopted the woolly mammoth as its official mascot; two mammoth replicas appear regularly at town events and are reputed to have weather forecasting abilities.

Many of the present day counties were formed from larger counties which were broken up as the populations in the region continued to grow. Southwest Virginia is also the result of parts of Virginia which broke off or revolted, such as Kentucky and West Virginia. During the American Revolution, residents from southwest Virginia were among those who participated in the Battle of King's Mountain. As the story goes, when a British major threatened to lay waste to the mountain region, the men decided they'd take the battle to him instead. They marched over the mountains to confront him at what became a decisive battle in the Revolutionary War—a victory that remains important in the psyche of many residents of the region, who are still proud of their ancestors' contribution.

In the Civil War, Southwest Virginia was deeply divided between sentiment for the Union and the Confederacy and was subject to guerilla warfare. The only major battle to occur in the area was the Battle of Saltville, while many skirmishes occurred throughout much of the region. In 1864, Union General George Stoneman led a devastating raid into Southwest Virginia, destroying the saltworks in Saltville and burning all that he thought useful to the Confederates. At the time, the saltworks were considered a very important strategic target.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, extractive industries became important in the region, especially the cutting of timber and coal mining. In recent years, historians have worked to document life in the coal camps as it was in the early 20th century because many of these communities have since been abandoned or demolished. As the coal industry became more mechanized, the number of jobs has decreased but mining has become very high-tech. The coalfield region has experienced a significant loss of population over the last generation, resulting in shrinking political representation and a variety of local issues, including the need to consolidate schools.

Manufacturing, which did well during part of the 20th century, has also declined in Southwest Virginia despite local officials' efforts to recruit new industry. Tobacco has declined since the buyout of the federal quota program, but Virginia has made wise use of its money from the health-related tobacco settlements, devoting much of it to economic development in the state's tobacco-growing regions, which include part of Southwest Virginia. Since the early 2000s, natural gas extraction has grown into an important industry, particularly in the coalfield region. Throughout Southwest Virginia, tourism has begun to take off as an important industry.

Geography

The Appalachian Mountains have the most direct impact upon the geography of Southwest Virginia and are often credited for isolating its residents from the rest of the commonwealth. Southwest Virginia falls into the ridge and valley and the Blue Ridge portions of the range. Within the mountains, coal fields have been one of the sources of the significant economic booms in the region. The major river of the region is the New River, credited as the oldest river in North America.

Flooding has been epidemic in the more mountainous areas, with major floods occurring about once every other decade with great loss of life and property. Such disasters have encouraged local precautions to prevent future problems, such as the Grundy Flood Control and Redevelopment Project, in Grundy, Virginia, a multimillion-dollar effort to protect the town from future flooding.[2] This federally funded project moved an entire town up off of the river bank and, on a site blasted out of a mountainside, replaced its flood-razed shopping district with a new shopping center anchored by Walmart.

Southwest Virginia also has a lot of public land, which provides opportunities to experience the region's natural environment. Hiking, biking, backpacking and kayaking are all popular in the region. Examples of Southwest Virginia recreation destinations include the Virginia Creeper Trail, where visitors can ride a shuttle van to the top of the mountain and ride down on their bicycles, and the New River, where visitors can paddle down the river with a guide.

Cities and towns

- Abingdon - town

- Blacksburg – largest town

- Bland – unincorporated census-designated place, but a county seat nonetheless

- Bristol

- Buena Vista

- Bluefield - town

- Christiansburg – town

- Clintwood - town

- Covington

- Galax

- Gate City – town

- Grundy

- Lexington

- Marion - town

- Martinsville

- Norton – smallest city

- Radford

- Roanoke – largest city, and largest municipality of any type

- Salem

- Wytheville – town

Political representation

Like the rest of the commonwealth, Southwest Virginia is represented by Senators Mark Warner and Tim Kaine in the United States Senate. In the House of Representatives, by the narrowest and almost to the largest definition of Southwest Virginia, representation falls largely under Representative Morgan Griffith of the 9th Congressional District. In 2010, Griffith defeated long-time representative Rick Boucher. Boucher had previously been a long term representative of the region in Congress, spending more than twenty-four years in office as a Democrat. His predecessor was William C. Wampler, a Republican, who had served a nearly equally long term of over eighteen years prior to his political defeat by Boucher. Republican Ben Cline of Rockbridge County represents the 6th Congressional District which also covers Lynchburg and much of the Shenandoah Valley. Republican Bob Goodlatte represented the 6th district for 26 years before retiring in 2019. Since most of Southwest Virginia has experienced little to no population growth in recent decades, the 9th district has begun to encroach into areas previously in the 5th and 6th districts.

Southwest Virginia's delegation to the Virginia General Assembly is known for sticking together, regardless of party. Democrats and Republicans from Southwest Virginia have a reputation for putting region above party, presenting a united front to ensure that money and resources make it to their end of the state. It's often remarked that the region is closer to several other states' capitals than it is to the Virginia state capital of Richmond—and thus, they need to work together if they hope to be heard. As a largely rural and relatively poor area of the state, Southwest Virginia is often at odds politically with wealthier, more urban parts of Virginia, which naturally have different priorities. Even so, several leaders from the region have gone on to have significant statewide or national influence.

Southwest Virginia's current state senators include -Bill Carrico (R-Independence) -Ben Chafin (R-Lebanon) -John Edwards (D-Roanoke) Its current state delegates include -Terry Kilgore (R-Gate City) -Israel O'Quinn (R-Bristol) -Will Morefield (R-Tazewell) -Todd Pillion (R-Abingdon) -Chris Hurst (D-Blacksburg)

Education

Southwest Virginia is home to several institutions of higher education, the largest of which is Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (better known as "Virginia Tech"), in Blacksburg. Virginia Tech is the largest research university in the state as well as the largest employer in Montgomery County.

Emory and Henry College is a highly respected private college near Abingdon and is recognized for its strong element of community service.

There are two medical schools in Blacksburg, and efforts are underway to develop a third in Abingdon. Professional schools—including schools of law and pharmacy—have been developed in recent years in Buchanan County, which is located in Southwest Virginia's coalfield region. There is also an effort within the region to help make higher education more accessible to students graduating from high school, particularly through partnerships between community colleges and other educational institutions.

List of colleges and universities

- Appalachian College of Pharmacy

- Appalachian School of Law

- Bluefield College

- Emory and Henry College

- Ferrum College

- Hollins University

- Jefferson College of Health Sciences

- Mountain Empire Community College

- New River Community College

- Patrick Henry Community College

- Radford University

- Roanoke College

- Southwest Virginia Community College

- Southern Virginia University

- University of Virginia's College at Wise

- Virginia College of Osteopathic Medicine

- Virginia Highlands Community College

- Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine

- Virginia Military Institute

- Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

- Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute

- Virginia Western Community College

- Washington and Lee University

- Wytheville Community College

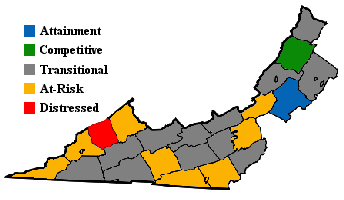

Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission was formed in 1965 to aid economic development in the Appalachian region, which was lagging far behind the rest of the nation on most economic indicators. The Appalachian region currently defined by the Commission includes 420 counties in 13 states, including the westernmost counties and cities in Virginia. The Commission gives each county one of five possible economic designations— distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, or attainment— with "distressed" counties being the most economically endangered and "attainment" counties being the most economically prosperous. These designations are based primarily on three indicators— three-year average unemployment rate, market income per capita, and poverty rate. For data collection purposes, independent cities within the designated region are grouped with an adjacent county.[3]

In 2003, Appalachian Virginia— which included most of Southwestern Virginia— had a three-year average unemployment rate of 5.7%, compared with 3.8% statewide and 5.5% nationwide. In 2002, Appalachian Virginia had a per capita market income of $16,901, compared with $29,279 statewide and $26,420 nationwide. In 2000, Appalachian Virginia had a poverty rate of 15.7%, compared to 9.6% statewide and 12.4% nationwide. Only one Virginia county— Dickenson— was designated "Distressed," while eight— Buchanan, Carroll (includes Galax), Craig, Grayson, Lee, Montgomery (includes Radford), Smyth, and Wise (includes Norton)— were designated "at-risk." Botetourt County was the only county given the "attainment" designation, and Bath was the only county designated "competitive." Most Appalachian Virginia counties were designated "transitional," meaning they lagged behind the national average on one of the three key indicators. Montgomery County had Appalachian Virginia's highest poverty rating, with 24.5% of its residents living below the poverty line. Botetourt had Appalachian Virginia's highest per capita income ($27,835) and lowest unemployment rate (2.7%).[3]

See also

References

- Mayer, Holzheimer. "Virginia's Creative Economy" (PDF). Virginia Tech.

- Article on Representative Rich Boucher's website on Grundy flood control

- Appalachian Regional Commission Online Resource Center Archived 2010-01-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved: 15 May 2009.