Middlesex County, Virginia

Middlesex County is a county located on the Middle Peninsula in the U.S. state of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 10,959.[2] Its county seat is Saluda.[3]

Middlesex County | |

|---|---|

Middlesex County Courthouse in Saluda | |

Seal | |

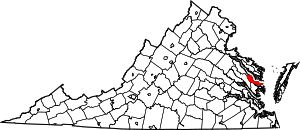

Location within the U.S. state of Virginia | |

Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 37°37′N 76°31′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1673 |

| Seat | Saluda |

| Largest town | Urbanna |

| Area | |

| • Total | 211 sq mi (550 km2) |

| • Land | 130 sq mi (300 km2) |

| • Water | 80 sq mi (200 km2) 38.2% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 10,959 |

| • Estimate (2018)[1] | 10,769 |

| • Density | 52/sq mi (20/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

History

This area was long settled by indigenous peoples; those encountered by Europeans were of the Algonquian-speaking peoples, part of loose alliance of tribes known as the Powhatan Confederacy. The Nimcock had a village on the river where Urbanna was later developed. English settlement of the area began around 1640, with the county being officially formed in 1669 from a part of Lancaster County. This settlement pushed the Nimcock upriver. The county's only incorporated town, Urbanna, was established by the colonial Assembly in 1680 as one of 20 50-acre port towns designated for trade. It served initially as a port on the Rappahannock River for shipping agricultural products, especially the tobacco commodity crop. As the county developed, it became its commercial and governmental center.

The Rosegill Estate was developed as a plantation by Ralph Wormeley beginning in 1649, with construction of its major buildings through the 17th century. It served as the temporary seat of the colony under two royal Governors of Virginia, (Sir Henry Chicheley, who served under Thomas Culpeper, 2nd Baron Culpeper of Thoresway,[4] and Lord Francis Howard, 5th Baron Howard of Effingham). This and other plantations in the county were developed for the commodity crop of tobacco through the 18th century, which was highly dependent on the skilled labor of enslaved African Americans.

In the 19th century, many planters from the Upper South sold slaves to the Deep South after switching from tobacco to mixed crops, which required less labor. Others migrated to the Deep South to develop new land and plantations, taking slaves with them, as did Thomas Wingfield, who moved to Wilkes County, Georgia in 1783, accompanied by 23 slaves.[5] Following the American Civil War and emancipation, numerous freedmen stayed in the rural area of Middlesex County, working on the land for pay or a share of crops. Others moved to towns or cities as artisans, seeking more opportunities.

The Rosegill mansion continues to be used as a private residence to this day. Most of the land of the estate was purchased in the 21st century by a Northern Virginia development firm, which plans to develop it as a 700-home subdivision. An archaeological survey of the property included in the first phase of the planned development has revealed what appear to be parts of the Nimcock village. It also has uncovered evidence of the Rosegill slave community of African Americans.[6] The developer intends to proceed with building houses over a portion of the artifacts, which will render excavation and study of them impossible.

During the American Civil War, Urbanna was planned as the point of landing for General George B. McClellan's 1862 Peninsula Campaign of 1862 to take Richmond. McClellan shifted to use Fort Monroe as the starting point, almost doubling the distance by land that troops had to travel to the Confederate citadel. Delays in reaching the gates of Richmond allowed the Confederates ample time to erect substantial defensive batteries, contributing to the Union failure in this campaign.

The Historic Middlesex County Courthouse was built in 1850–1874 by architects William R. Jones and John P. Hill. It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[7] Construction of a new 21st-century county courthouse[8] began in 2003 and was completed in 2004. It was not occupied until September 2007, however, due to a legal dispute between the county and the architect. The Historic Courthouse has been remodeled and now serves as the Board of Supervisors meeting room and the Registrar's Office.[9]

Urbanna was incorporated on April 2, 1902, comprising an area of 0.49 square miles (1.27 km2). The Town of Urbanna remains the county's largest commercial center and its only incorporated area. The county seat was moved to the Village of Saluda on U.S. Route 17. To the east, almost to Stingray Point, the Village of Deltaville is situated on State Route 33 between the mouths of the Rappahannock and Piankatank rivers. Once a major center for wooden boat building, the village has become known as a commercial and recreational center. Its waterfront and east to Stingray Point how has many marinas, with a concentration on Broad Creek.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 211 square miles (550 km2), of which 130 square miles (340 km2) is land and 80 square miles (210 km2) (38.2%) is water.[10]

Middlesex County is located at the eastern end of Virginia's Middle Peninsula region. The County is bounded by the Rappahannock River to the north, by the Chesapeake Bay to the east, by the Piankatank River and Dragon Run Swamp to the southwest, and by Essex County to the northwest. The County has a land area of 132 square miles (342 km2) and 135 miles (217 km) of shoreline.

Adjacent counties

- Lancaster County – North

- Mathews County – South

- Gloucester County – Southwest

- King and Queen County – West

- Essex County – Northwest

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 4,140 | — | |

| 1800 | 4,203 | 1.5% | |

| 1810 | 4,414 | 5.0% | |

| 1820 | 4,057 | −8.1% | |

| 1830 | 4,122 | 1.6% | |

| 1840 | 4,392 | 6.6% | |

| 1850 | 4,394 | 0.0% | |

| 1860 | 4,364 | −0.7% | |

| 1870 | 4,981 | 14.1% | |

| 1880 | 6,252 | 25.5% | |

| 1890 | 7,458 | 19.3% | |

| 1900 | 8,220 | 10.2% | |

| 1910 | 8,852 | 7.7% | |

| 1920 | 8,157 | −7.9% | |

| 1930 | 7,273 | −10.8% | |

| 1940 | 6,673 | −8.2% | |

| 1950 | 6,715 | 0.6% | |

| 1960 | 6,319 | −5.9% | |

| 1970 | 6,295 | −0.4% | |

| 1980 | 7,719 | 22.6% | |

| 1990 | 8,653 | 12.1% | |

| 2000 | 9,932 | 14.8% | |

| 2010 | 10,959 | 10.3% | |

| Est. 2018 | 10,769 | [1] | −1.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] 1790–1960[12] 1900–1990[13] 1990–2000[14] 2010–2013[2] | |||

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 9,932 people, 4,253 households, and 2,913 families residing in the county. The population density was 76 people per square mile (29/km²). There were 6,362 housing units at an average density of 49 per square mile (19/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 78.50% White, 20.13% Black or African American, 0.25% Native American, 0.12% Asian, 0.41% from other races, and 0.58% from two or more races. 0.55% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 4,253 households out of which 32.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.10% were married couples living together, 9.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.50% were non-families. 27.10% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.73.

In the county, the population was spread out with 19.20% under the age of 18, 5.10% from 18 to 24, 22.90% from 25 to 44, 30.30% from 45 to 64, and 22.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females there were 92.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.50 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $36,875, and the median income for a family was $43,440. Males had a median income of $30,842 versus $23,659 for females. The per capita income for the county was $22,708. About 9.70% of families and 13.00% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.70% of those under age 18 and 10.70% of those age 65 or over.

Ethnicity

As of 2016 the largest self-identified ethnic groups/ancestries in Middlesex County are:

- English - 29.9%

- Irish - 14.1%

- German - 11.5%

- American - 10.8%

- French - 3.7%[16]

Communities

Town

Census-designated places

Other unincorporated communities

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 61.0% 3,670 | 35.0% 2,108 | 4.0% 239 |

| 2012 | 59.5% 3,619 | 39.0% 2,370 | 1.5% 91 |

| 2008 | 59.0% 3,545 | 39.8% 2,391 | 1.2% 70 |

| 2004 | 62.0% 3,336 | 35.6% 1,914 | 2.4% 127 |

| 2000 | 60.7% 2,844 | 35.6% 1,671 | 3.7% 174 |

| 1996 | 49.8% 2,141 | 39.7% 1,704 | 10.5% 452 |

| 1992 | 47.5% 2,224 | 34.1% 1,597 | 18.4% 864 |

| 1988 | 64.0% 2,571 | 33.9% 1,361 | 2.1% 86 |

| 1984 | 67.2% 2,612 | 31.0% 1,206 | 1.7% 67 |

| 1980 | 54.1% 1,810 | 41.7% 1,395 | 4.2% 139 |

| 1976 | 52.9% 1,608 | 43.2% 1,312 | 3.9% 119 |

| 1972 | 69.3% 1,697 | 29.6% 724 | 1.1% 28 |

| 1968 | 39.6% 809 | 28.2% 575 | 32.2% 658 |

| 1964 | 51.1% 1,019 | 48.8% 973 | 0.2% 3 |

| 1960 | 58.7% 823 | 40.9% 574 | 0.4% 5 |

| 1956 | 58.0% 721 | 27.2% 338 | 14.8% 184 |

| 1952 | 57.7% 705 | 41.5% 507 | 0.7% 9 |

| 1948 | 30.8% 271 | 52.0% 457 | 17.2% 151 |

| 1944 | 22.8% 186 | 76.8% 627 | 0.4% 3 |

| 1940 | 17.5% 125 | 82.2% 586 | 0.3% 2 |

| 1936 | 15.8% 123 | 83.6% 653 | 0.6% 5 |

| 1932 | 17.1% 127 | 80.2% 595 | 2.7% 20 |

| 1928 | 44.5% 318 | 55.5% 397 | |

| 1924 | 14.9% 78 | 83.8% 438 | 1.3% 7 |

| 1920 | 27.9% 170 | 71.9% 438 | 0.2% 1 |

| 1916 | 29.4% 155 | 70.6% 373 | |

| 1912 | 24.4% 128 | 71.4% 374 | 4.2% 22 |

References

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Billings, Warren M. "Sir Henry Chicheley (1614 or 1615–1683)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "Our Georgia Roots" website, accessed 9 November 2014

- Daily Press, Jan. 1, 2008

- "National Register of Historical Places - VIRGINIA (VA), Middlesex County". www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com.

- "Middlesex Courthouse Complex". middlesex.va.us.

- "Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes". Middlesex County, Virginia. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

Further reading

- Gray, Louise E., et al. Historic Buildings in Middlesex County, Virginia: 1650–1875. (Delmar Publishing, Charlotte, NC, 1976.)

- Rutman, Darrett Bruce; Rutman, Anita H. A Place in Time: Middlesex County, Virginia 1650–1750. (W.W. Norton & Co, 1986).

- Lewis, Troy "Gas Money" (Middletown, DE, 2015)

- Chowning, Larry " Signatures In Time: A Living History of Middlesex County, Virginia (Carter Printing Co., Richmond, VA 2012)

External links

- official website

- Middlesex County Public Schools

- Southside Sentinel (county newspaper)

- 1755 map of Middlesex County, Rappahannock River, Piankatank River and Chesapeake Bay (excerpted from A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. at the Library of Congress)