Spanish moss

Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) is an epiphytic flowering plant that often grows upon larger trees in tropical and subtropical climates, native to much of Mexico, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Central America, South America, the Southern United States, West Indies and is also naturalized in Queensland (Australia). It is known as "grandpas beard" in French Polynesia.[2] In the United States from where it is most known, it is commonly found on the southern live oak (Quercus virginiana) and bald-cypress (Taxodium distichum) in the lowlands, swamps, and marshes of the mid-atlantic and southeastern United States from central Delaware to southeastern Virginia to Florida and west to Texas and southern Arkansas.[3][4]

| Spanish moss | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Bromeliaceae |

| Genus: | Tillandsia |

| Subgenus: | Tillandsia subg. Diaphoranthema |

| Species: | T. usneoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Tillandsia usneoides | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

This plant's specific name usneoides means "resembling Usnea".[5] While it superficially resembles its namesake, Spanish moss is neither a moss nor a lichen like Usnea, and it is not native to Spain. Instead, it is a flowering plant (angiosperm) in the family Bromeliaceae (the bromeliads) which grows hanging from tree branches in full sun through partial shade. Formerly this plant has been placed in the genera Anoplophytum, Caraguata, and Renealmia.[6] The northern limit of its natural range is Northampton County,[7] Virginia, with colonial-era reports in southern Maryland[8][9][10][11] where no populations are now known to be extant.[11] The primary range is in the southeastern United States (including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands), through Argentina, growing where the climate is warm enough and has a relatively high average humidity. It has been introduced to similar locations around the world, including Hawaii and Australia.

Description

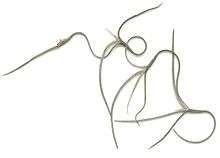

The plant consists of one or more slender stems bearing alternate thin, curved or curly, heavily scaled leaves 0.8–2.4 in (2.0–6.1 cm) long and 0.04 in (1 mm) broad, that grow vegetatively in chain-like fashion (pendant), forming hanging structures up to 240 in (6.1 m)[12] in length. The plant has no aerial roots[12] and its brown, green, yellow, or grey flowers are tiny and inconspicuous. It propagates both by seed and vegetatively by fragments that blow on the wind and stick to tree limbs or are carried by birds as nesting material.

Ecology

Spanish moss is an epiphyte which absorbs nutrients and water through its leaves from the air and rainfall.

While it rarely kills the tree upon which it grows, it can occasionally become so thick that it shades the tree's leaves and lowers its growth rate.[12]

In the southern U.S., the plant seems to show a preference for growth on southern live oak (Quercus virginiana) and bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) because of these trees' high rates of foliar mineral leaching (calcium, magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus) providing an abundant supply of nutrients to the plant,[13] but it can also colonize other tree species such as sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), crepe-myrtles (Lagerstroemia spp.), other oaks, and even pines.

Spanish moss shelters a number of creatures, including rat snakes and three species of bats. One species of jumping spider, Pelegrina tillandsiae, has been found only on Spanish moss.[14] Chiggers, though widely assumed to infest Spanish moss, were not present among thousands of other arthropods identified in one study.[15]

Culture and folklore

Due to its propensity for growing in subtropical humid southern locales like Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, east and south Texas, and extreme southern Virginia, the plant is often associated with Southern Gothic imagery and Deep South culture.

One story of the origin of Spanish moss is called "The Meanest Man Who Ever Lived". The man's white hair grew very long and got caught on trees.[16]

Spanish moss was introduced to Hawaii in the 19th century, and became a popular ornamental and lei plant.[17] On Hawai'i it is often called "Pele's hair" after Pele the Hawaiian goddess. The term "Pele's hair" is also used to refer to a type of filamentous volcanic glass.

Human uses

Spanish moss has been used for various purposes, including building insulation, mulch, packing material, mattress stuffing, and fiber. In the early 1900s it was used commercially in the padding of car seats.[18] In 1939 over 10,000 tons of processed Spanish-moss was produced.[19] It is still collected today in smaller quantities for use in arts and crafts, or for beddings for flower gardens, and as an ingredient in the traditional wall covering material bousillage. In some parts of Latin America and Louisiana Spanish moss is used in Nativity scenes.

In the desert regions of the southwestern United States, dried Spanish moss plants are sometimes used in the manufacture of evaporative coolers, colloquially known as swamp coolers (and in some areas as "desert coolers"). These are used to cool homes and offices much less expensively than using air conditioners. A pump squirts water onto a pad made of Spanish moss plants. A fan then pulls air through the pad and into the building. Evaporation of the water on the pads serves to reduce the air temperature, thus cooling the building.[20]

Cultivars

- Tillandsia 'Maurice's Robusta'[21]

- Tillandsia 'Munro's Filiformis'[22]

- Tillandsia 'Odin's Genuina'[23]

- Tillandsia 'Spanish Gold'[24]

- Tillandsia 'Tight and Curly'[25]

Hybrids

- Tillandsia 'Nezley' (Tillandsia usneoides × mallemontii)[26]

- Tillandsia 'Kimberly' (Tillandsia usneoides × recurvata)[27]

- Tillandsia 'Old Man's Gold' (Tillandsia crocata × usneoides)[28]

References

- "Tillandsia usneoides". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, Tillandsia usneoides

- Luther, Harry E.; Brown, Gregory K. (2000). "Tillandsia usneoides". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 22. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- "Tillandsia usneoides". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- Damrosch, B.; Neal, B. (2003). Gardener's Latin: A Lexicon. Chapel Hill, N.C: Algonquin Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-56512-743-2. OCLC 856021571. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Tillandsia". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

- Times-Dispatch, REX SPRINGSTON Richmond. "Virginia scientists search for northernmost realm of Spanish moss". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- John Ray 1688

- "Plants profile for Tillandsia usneoides". USDA.

- "Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Plants of Maryland" (PDF).

- Brown, M.L., and R.G. Brown (1984). Herbaceous plants of Maryland. Baltimore: Port City Press, Inc.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Tillandsia usneoides". Floridata Plant Encyclopedia.

- Schlesinger, William H.; Marks, P. L. (1977). "Mineral Cycling and the Niche of Spanish Moss, Tillandsia usneoides L.". American Journal of Botany. 64 (10): 1254–1262. doi:10.2307/2442489. JSTOR 2442489.

- Wildlife, State of Texas, Parks and. "Flora Fact:| Spanish Moss Serves as Nature's Draperies". www.tpwmagazine.com. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- Whitaker Jr., J; Ruckdeschel, C. (2010). "Spanish Moss, the Unfinished Chigger Story". Southeastern Naturalist. 9 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1656/058.009.0107.

- Friedman, Amy; Johnson, Meredith (May 28, 2017). "The Meanest Man Who Ever Lived (An American Folktale)". Uexpress. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- "Nā Lei o Hawai'i – Types of Lei". Archived from the original on 2013-01-03.

- "Hair From Trees....Spanish-moss is new upholstering material". Popular Science. June 1937.

- Adams, Dennis. Spanish Moss: Its Nature, History and Uses. Beaufort County Library, SC.

- Gutenberg, Arthur William (1955). The Economics of the Evaporative Cooler Industry in the Southwestern United States. Stanford University Graduate School of Business. p. 167.

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Maurice's Robusta'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Munro's Filiformis'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Odin's Genuina'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Spanish Gold'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Tight and Curly'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Nezley'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Kimberly'

- Bromeliad Cultivar Registry: Tillandsia 'Old Man's Gold'

- Mabberley, D.J. 1987. The Plant Book. A Portable Dictionary of the Higher Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-34060-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |