Vindobona

Vindobona (from Gaulish windo- "white" and bona "base/bottom") was a Roman military camp on the site of the modern city of Vienna in Austria. The settlement area took on a new name in the 13th century, being changed to Berghof, or now simply known as Alter Berghof (the Old Berghof).[1]

Around 15 BC, the kingdom of Noricum was included in the Roman Empire. Henceforth, the Danube marked the border of the empire, and the Romans built fortifications and settlements on the banks of the Danube, including Vindobona with an estimated population of 15,000 to 20,000.[2][3]

History

Early references to Vindobona are made by the geographer Ptolemy in his Geographica and the historian Aurelius Victor, who recounts that emperor Marcus Aurelius died in Vindobona on 17 March 180 from an unknown illness while on a military campaign against invading Germanic tribes. Today, there is a Marc-Aurelstraße (English: Marcus Aurelius street) near the Hoher Markt in Vienna.

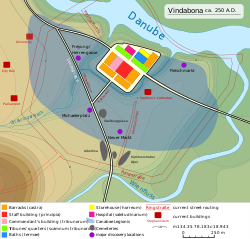

Vindobona was part of the Roman province Pannonia, of which the regional administrative centre was Carnuntum. Vindobona was a military camp with an attached civilian city (Canabae). The military complex covered an area of some 20 hectares, housing about 6000 men where Vienna’s first district now stands. The Danube marked the border of the Roman Empire, and Vindobona was part of a defensive network including the camps of Carnuntum, Brigetio and Aquincum. By the time of Emperor Commodus, four legions (X Gemina, XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, I Adiutrix and II Adiutrix) were stationed in Pannonia.[4]

Vindobona was provisioned by the surrounding Roman country estates (Villae rusticae). A centre of trade with a developed infrastructure as well as agriculture and forestry developed around Vindobona. Civic communities developed outside the fortifications (canabae legionis), as well another community that was independent of the military authorities in today's third district. It has also been proven that a Germanic settlement with a large marketplace existed on the far side of the Danube from the second century onwards.

The asymmetrical layout of the military camp, which was unusual for the otherwise standardised Roman encampments, is still recognisable in Vienna’s street plan: Graben, Naglergasse, Tiefer Graben, Salzgries, Rabensteig, Rotenturmstraße. The oblique camp border along today's street Salzgries was probably caused by a tremendous flood of the River Danube that occurred during the 3rd century and eroded a considerable part of the camp.[5] The name “Graben” (English: ditch) is believed to hark back to the defensive ditches of the military camp. It is thought that at least parts of the walls still stood in the Middle Ages, when these streets were laid out, and thus determined their routes. The Berghof was later erected in one corner of the camp.

Rebuilt after Germanic invasions in the second century, the town remained a seat of Roman government through the third and fourth centuries.[6][7] The population fled after the Huns invaded Pannonia in the 430s and the settlement was abandoned for several centuries.[8][9]

Evidence for the Roman presence in Vindobona

Archaeological remains

.jpg)

Remains of the Roman military camp have been found at many sites in the centre of Vienna. The centre of the Michaelerplatz has been widely investigated by archaeologists. Here, traces of a Roman legionary outpost (canabae legionis) and of a crossroad have been found.[10] The centrepiece of the current design of the square is a rectangular opening that evokes the archaeological excavations at the site and shows wall remains that have been preserved from different epochs.

Part of a Roman canal system is underneath the fire station am Hof.[11]

Directly under the Hoher Markt are the remains of two buildings unearthed during the canalisation works of 1948/49 and made accessible to the public. After further excavation, a showroom was opened in 1961. For this purpose some of the original walls had to be removed; white marks on the floor show the spots where. The buildings, which are separated from one another by a road, housed an officer and his family. In 2008 this Roman ruins exhibit was expanded into the Museum of the Romans.[12] Only a small portion can today be seen, for the majority of the remains are still located underneath the square and south of it.

The remains of the walls date from different phases from the 1st to the 5th century AD. The houses were typical Roman villas, with living quarters and space for working set around a middle courtyard with columned halls.[13]

Evidence for the Roman military presence

Over 3,000 stamped bricks, several stone monuments and written sources prove that several legions, cavalry units and marines were stationed in Vindobona. Around 97 AD, Legio XIII Gemina was responsible for construction of the legionary camps. Because of the wars in Dacia, they were pulled out and redeployed in 101 AD. A decade later, Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix followed. Legio X Gemina from Aquincum arrived in 114 AD and remained in Vindobona until the 5th century.

About 6,000 soldiers were stationed in the Roman camp. Many of them were free from active duty during peaceful times and had other jobs. These so-called immunes were needed for the supply of goods and for the production and maintenance of weapons and commodities. They also extracted stone from quarries and wood from forests, produced bricks, and maintained the streets, bridges and the water system. Administrating the camp and ensuring its security required additional manpower.

Roman canals

The Romans provided their cities, including Vindobona, with clean potable water through an elaborate systems of Roman aqueducts, canals, and large subterranean pipes. Excavations have revealed that Vindobona received its supply through a 17 km long water pipeline. The source is in the Vienna Woods around today's Kalksburg. Wells, latrines and the thermae were supplied with water. Central buildings such as the commander's office and the hospital had their own supplies, as did the settlement outside the camp, where households had their own groundwater wells.

Archaeological excavations done over the last 100 years have discovered the following Roman water supply fragment locations:

- In the Zemlinskygasse: at numbers 2-4 - (23rd district, found in 1924)

- In the Breitenfurter Straße: at number 422 - (23rd district, in 1959)

- In the Rudolf Zeller-Gasse/Anton-Krieger-Gasse - (23rd district, 1992)

- In Atzgersdorf - (23rd district, 1902–1907)

- In the Tullnertalgasse: at number 76 - (23rd district, 1973)

- In the Lainergasse: at number 1 - (23rd district, 1958)

- In the Wundtgasse - (12th district, 1951)

- In the Rosenhügelstraße: at number 88 - (12th district, 1926)

- In the Fasangartenstraße: at number 49 - (12th district, 1916)

- In the Pacassistraße - (13th district, 1928)

- In the Sechshauserstraße: at number 7 - (15th district, 1879 - leading towards the first district)

Waste from the Roman camp was transported through an elaborate subterranean sewerage system that was planned from the beginning. The sewers were lined with brick walls and plates and ran beneath the main roads. Gradients were used in such a way that the waste water descended through the canals into the River Danube. Since the canals were up to two meters deep, they could be cleaned out regularly. Large waste was probably deposed at the slope of the river. In the civilian settlement, waste was deposed in former water wells and dumps.

Legacies in today's streets

The layout of a Roman camp (castra) was normally standardised. This has helped archaeologists to reconstruct what the camp must have looked like, despite the heavy rebuilding that has taken place in Vienna throughout the centuries. The basic contours of the camp, which was surrounded by a mighty wall with towers and three moats (today the Tiefer Graben, Naglergasse, Graben, and Rotenturmstraße) are identifiable. Along these axes, main roads connected the gates with one other. The main buildings were the commander's headquarters, the Palace of the Legate, the houses of the staff officers, and the thermae. At right angles to these, the soldiers' accommodation, a hospital, workshops, and mews (stables) were constructed.

Popular culture

- In the American film Gladiator (2000), Maximus (Russell Crowe) fights in the battle of Vindobona under the order of Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris).[14][15] There are also two lines that make reference to Vindobona. In one, the lead character's servant, Cicero, trying to get the attention of Lucilla, states, "I served your father at Vindobona!"[16] In the other, the lead character asks if anyone in his group of gladiators has served in the army, to which an anonymous fighter responds, "I served with you at Vindobona."

- The historical novel Votan by Welsh writer John James begins in "Vindabonum" and imagines 2nd century C.E. life there.

References

- The Older Berghof in Vienna (German). Today, the site is more commonly associated with Hoher Markt and Wiener Neustädter Hof, a building in today's Sterngasse 3. Berghof was the name of the mansion, which had evolved from the initial settlement with the walls of the Roman baths. It was originally the only building in Vienna to be built by a certain pagan, presumably an Avaricum dignitary, eventually becoming a fortified town. The place is mentioned in Jans Enikel's "Fürstenbuch" (around 1270) (vide: Jeff Bernhard / Dieter Bietak: The Wiener Neustädter Hof alias Berghof - a probe into the Year Zero, Frankfurt am Main/Berlin/Bern 1997, p. 247).

- Bowman, Alan; Wilson, Andrew (2011-12-22). Settlement, Urbanization, and Population. ISBN 9780199602353.

- Ziak, Karl (1964). "Unvergängliches Wien: Ein Gang durch die Geschichte von der Urzeit bis zur Gegenwart".

- Stephen Dando-Collins (2012). Legions of Rome: The definitive history of every Roman legion. Quercus Publishing. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

'...at the start of AD 193...On 13 April, the legions of Pannonia - the 10th Gemina and 14th Gemina Martia Victrix in his own province, and the 1st and 2nd Adiutrix legions from neighbouring Lower Pannonia...'

- Reconstruction of the ancient relief of downtown Vienna (in German)

- Southern Germany and Austria, Including the Eastern Alps: Handbook for Travellers. Karl Baedeker. 1873. p. 177. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

'By the end of the third century Vindobona had become a municipal town, and being the seat of the Roman civil and military government, continued to flourish until the invasion of the Huns in the 5th century.'

- J. Sydney Jones (2014). Viennawalks: Four Intimate Walking Tours of Vienna's Most Historic and Enchanting Neighborhoods. Henry Holt and Company. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

'Vindobona was destroyed suring the Germanic invasions of the latter part of the second century and was rebuilt after those invasions were finally repelled, but the Roman era had had its peak....by 180...Roman order was restored to Pannonia. But it was a tenuous order, holding doggedly on for another two centuries until the final withdrawal of the Roman troops and destruction of Vindobona in the early fifth century.'

- Southern Germany and Austria, Including the Eastern Alps: Handbook for Travellers. Karl Baedeker. 1873. p. 177. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

'Vindobona ... continued to flourish until the invasion of the Huns in the 5th century. From that date the Roman Vindobona disappears from the history until the year 791.'

- Rob Collins, Matt Symonds, Meike Weber (2015). Roman Military Architecture on the Frontiers: Armies and Their Architecture in Late Antiquity. Oxbow Books. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

'...Consequently, Vindobona became increasingly depopulated over the course of the first half of the 5th century. The present state of research indicated that the definite end of the settlement within the old fortress occurred during the 430s AD, when the Huns finally seized control of the province of Pannonia...The intramural area of Vindobona has provided no evidence of settlement activity from the mid 5th century through until at least the 9th century.'

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wien Museum | Archäologisches Grabungsfeld Michaelerplatz(in German)

- Wien Museum | Römische Baureste Am Hof, Vienna Museum (in German)

- "Die Römer kommen nach Wien", ORF 10 May 2008 (in German)

- Wien Museum | Römische Ruinen Hoher Markt(in German)

- Villapalos Salas, Gustavo; San Miguel Pérez, Enrique (September 1, 2014). Lecciones de Historia del Derecho Español. Editorial Universitaria Ramon Areces. p. 38. ISBN 9788499611785.

- Gilliland, Charles (November 14, 2016). The Gospel of Matthew Through the Eyes of a Cop: A Devotional for Law Enforcement Officers. WestBow Press. p. 162. ISBN 9781490898377.

- Cyrino, Monica Silveira (February 9, 2009). Big Screen Rome. John Wiley & Sons. p. 209. ISBN 9781405150323.

Further reading

- Michaela Kronberger: Siedlungschronologische Forschungen zu den canabae legionis von Vindobona. Die Gräberfelder (Monographien der Stadtarchäologie Wien Band 1). Phoibos Verlag, Wien 2005. (in German)

- Christine Ranseder e.a., Michaelerplatz. Die archäologischen Ausgrabungen. Wien Archäologisch 1, Wien 2006. ISBN 3-901232-72-9. (in German)

- Vindobona. Die Reise in das antike Wien. DVD-Rom, 2004. (in German)

- Vindobona II. Wassertechnik des antiken Wiens. DVD-Rom, 2005. (in German)

External links

![]()

- Wien Museum | Ausgrabungsstätten (in German)

- Forschungsgesellschaft Wiener Stadtarchäologie | Legionslager Vindobona (in German)

- Animationsfilme zu vindobona (in German)

- Seite mit sehenswerter Rekonstruktion des Lagertores (in German)

- Livius.org: Vindobona (Vienna)

- Austrian Mint Coin Features Vindobona

- Bursche, A., L. Pitts, P. Kaczanowski, E. Krekovič, R. Madyda‑Legutko, R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. "Places: 128537 (Vindobona)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)