Tutsi

The Tutsi (/ˈtʊtsi/;[3] Rwanda-Rundi pronunciation: [ɑ.βɑ.tuː.t͡si]), or Abatutsi, are a social class or ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. Historically, they were often referred to as the Watutsi,[4] Watusi,[4] Wahuma, Wahima or the Wahinda. The Tutsi form a subgroup of the Banyarwanda and the Barundi people, who reside primarily in Rwanda and Burundi, but with significant populations also found in DR Congo, Tanzania and Uganda.[5]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| >4,200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| 1.5 million (14% of total population) | |

| 1.5 million (14% of total population) | |

| 1.2 million (2% of total population in 2007)[1] | |

| n/a | |

| n/a | |

| n/a | |

| n/a | |

| Languages | |

| Rwanda-Rundi, French, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hutu, Twa, Nilotic peoples (partially), Banyankole, Bahororo, Bakiga, Batooro and Banyoro. [2] | |

Tutsis are the second largest population division among the three largest groups in Rwanda and Burundi; the other two being the Hutu (largest) and the Twa (smallest). Small numbers of Hema and Kiga people also live near the Tutsi in Rwanda. The Northern Tutsi who reside in Rwanda are called Ruguru (Banyaruguru),[6] while southern Tutsi who live in Burundi are known as Hima, the Banyamulenge do not have a territory.[7]

Origins and classification

The definitions of "Hutu" and "Tutsi" people may have changed through time and location. Social structures were not stable throughout Rwanda, even during colonial times under the Belgian rule. The Tutsi aristocracy or elite was distinguished from Tutsi commoners, and wealthy Hutu were often indistinguishable from upper-class Tutsi.

When the Belgian colonists conducted censuses, they wanted to identify the people throughout Rwanda-Burundi according to a simple classification scheme. They defined "Tutsi" as anyone owning more than ten cows (a sign of wealth) or with the physical feature of a longer nose, or longer neck, commonly associated with the Tutsi.

Tutsis usually were said to have arrived in the Great Lakes region from the Horn of Africa.[8][9]

Tutsis are considered to be of Cushitic origin[10] by some researchers , although they do not speak a Cushitic language , and have lived in the areas where they are for at least 400 years, leading to considerable intermarriage with the Hutu in the area. Due to the history of intermingling and intermarrying of Hutus and Tutsis, ethnographers and historians have lately come to agree that Hutu and Tutsis cannot be properly called distinct ethnic groups.[11][12]

Many analysts and also inhabitants of the Great Lakes Region oppose the Tutsi – as "Cushitics" – to Bantu people like the Hutu and several ethnic groups in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and e.g. in Uganda. However, Bantu is a linguistic classification (see the Bantu lemma as well as the lemma on "Bantu people – the latter says: Bantu people are the speakers of Bantu languages"). As the Tutsi speak the same Bantu language as the Hutu, they are Bantu (speaking) people.

Genetics

.jpg)

Y-DNA (paternal lineages)

Modern-day genetic studies of the Y-chromosome generally indicate that the Tutsi, like the Hutu, are largely of Bantu extraction (60% E1b1a, 20% B, 4% E-P2(xE1b1a)). Paternal genetic influences associated with the Horn of Africa and North Africa are few (under 3% E1b1b-M35), and are ascribed to much earlier inhabitants who were assimilated. However, the Tutsi have considerably more haplogroup B paternal lineages (14.9% B) than do the Hutu (4.3% B).[13]

Trombetta et al. (2015) found 22.2% of E1b1b in a small sample of Tutsis from Burundi, but no bearers of the haplogroup among the local Hutu and Twa populations.[2] The subclade was of the 4,000-year-old migrant[14] M293 variety, which suggests that the ancestors of Tutsis in this area may have assimilated some Southern Cushitic-speaking pastoralists.[15] Its parental marker E-V1515 is thought to have originated in the northern part of the Horn of Africa around 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[2][16]

mtDNA (maternal lineages)

There are no peer-reviewed genetic studies of the Tutsi's mtDNA or maternal lineages. However, Fornarino et al. (2009) report that unpublished data indicates that one Tutsi individual from Rwanda carries the India-associated mtDNA haplogroup R7.[17]

Autosomal DNA (overall ancestry)

In general, the Tutsi appear to share a close genetic kinship with neighboring Bantu populations, particularly the Hutus. However, it is unclear whether this similarity is primarily due to extensive genetic exchanges between these communities through intermarriage or whether it ultimately stems from common origins:

[...]generations of gene flow obliterated whatever clear-cut physical distinctions may have once existed between these two Bantu peoples – renowned to be height, body build, and facial features. With a spectrum of physical variation in the peoples, Belgian authorities legally mandated ethnic affiliation in the 1920s, based on economic criteria. Formal and discrete social divisions were consequently imposed upon ambiguous biological distinctions. To some extent, the permeability of these categories in the intervening decades helped to reify the biological distinctions, generating a taller elite and a shorter underclass, but with little relation to the gene pools that had existed a few centuries ago. The social categories are thus real, but there is little if any detectable genetic differentiation between Hutu and Tutsi.[18]

Tishkoff et al. (2009) found their mixed Hutu and Tutsi samples from Rwanda to be predominantly of Bantu origin, with minor gene flow from Afro-Asiatic communities (17.7% Afro-Asiatic genes found in the mixed Hutu/Tutsi population).[19]

Height

Their average height is 5 feet 9 inches (175 cm), although individuals have been recorded as being taller than 7 feet (213 cm).[20]

History

.png)

Prior to the arrival of colonists, Rwanda had been ruled by a Tutsi-dominated monarchy after mid-1600. Beginning in about 1880, Roman Catholic missionaries arrived in the Great Lakes region. Later, when German forces occupied the area during World War I, the conflict and efforts for Catholic conversion became more pronounced. As the Tutsi resisted conversion, missionaries found success only among the Hutu. In an effort to reward conversion, the colonial government confiscated traditionally Tutsi land and reassigned it to Hutu tribes.[21]

In Burundi, meanwhile, Tutsi domination was even more entrenched. A ruling faction, the Ganwa, soon emerged from amongst the Tutsi and assumed effective control of the country's administration.

The area was ruled as a colony by Germany (prior to World War I) and Belgium. Both the Tutsi and Hutu had been the traditional governing elite, but both colonial powers allowed only the Tutsi to be educated and to participate in the colonial government. Such discriminatory policies engendered resentment.

When the Belgians took over, they believed it could be better governed if they continued to identify the different populations. In the 1920s, they required people to identify with a particular ethnic group and classified them accordingly in censuses.

In 1959, Belgium reversed its stance and allowed the majority Hutu to assume control of the government through universal elections after independence. This partly reflected internal Belgian domestic politics, in which the discrimination against the Hutu majority came to be regarded as similar to oppression within Belgium stemming from the Flemish-Walloon conflict, and the democratization and empowerment of the Hutu was seen as a just response to the Tutsi domination. Belgian policies wavered and flip-flopped considerably during this period leading up to independence of Burundi and Rwanda.

Independence of Rwanda and Burundi (1962)

The Hutu majority in Rwanda had revolted against the Tutsi and was able to take power. Tutsis fled and created exile communities outside Rwanda in Uganda and Tanzania. Since Burundi's independence, more extremist Tutsi came to power and oppressed the Hutus, especially those who were educated.[22][23][24][25][26] Their actions led to the deaths of up to 200,000 Hutus.[27] Overt discrimination from the colonial period was continued by different Rwandan and Burundian governments, including identity cards that distinguished Tutsi and Hutu.

Burundi genocide (1993)

In 1993, Burundi's first democratically elected president, Melchior Ndadaye, a Hutu, was assassinated by Tutsi officers, as was the person entitled to succeed him under the constitution.[28] This sparked a genocide in Burundi between Hutu political structures and the Tutsi military, in which "possibly as many as 25,000 Tutsi" were murdered by the former and "at least as many" were killed by the latter.[29] Since the 2000 Arusha Peace Process, today in Burundi the Tutsi minority shares power in a more or less equitable manner with the Hutu majority. Traditionally, the Tutsi had held more economic power and controlled the military.[30]

Genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi (1994)

A similar pattern of events took place in Rwanda, but there the Hutu came to power in 1962. They in turn often oppressed the Tutsi, who fled the country. After the anti-Tutsi violence around 1959–1961, Tutsis fled in large numbers.

These exile Tutsi communities gave rise to Tutsi rebel movements. The Rwandan Patriotic Front, mostly made up of exiled Tutsi living primarily in Uganda, attacked Rwanda in 1990 with the intention of liberating Rwanda. The RPF had experience in organized irregular warfare from the Ugandan Bush War, and got much support from the government of Uganda. The initial RPF advance was halted by the lift of French arms to the Rwandan government. Attempts at peace culminated in the Arusha Accords.

The agreement broke down after the assassination of the Rwandan and Burundian Presidents, triggering a resumption of hostilities and the start of the Genocide against the Tutsi of 1994, in which the Hutu then in power killed an estimated 800,000–1,000,000 people, largely of Tutsi origin. Victorious in the aftermath of the genocide, the Tutsi ruled RPF came to power in July 1994.

Language

Tutsis speak Rwanda-Rundi as their native language. Rwanda-Rundi is subdivided into the Kinyarwanda and Kirundi dialects, which have been standardized as official languages of Burundi and Rwanda.

Culture

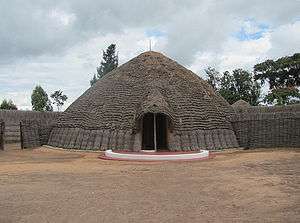

In the Rwanda territory, from the 15th century until 1961, the Tutsi were ruled by a king (the mwami). Belgium abolished the monarchy, following the national referendum that led to independence. By contrast, in the northwestern part of the country (predominantly Hutu), large regional landholders shared power, similar to Buganda society (in what is now Uganda).

Under their holy king, Tutsi culture traditionally revolved around administering justice and government. They were the only proprietors of cattle, and sustained themselves on their own products. Additionally, their lifestyle afforded them a lot of leisure time, which they spent cultivating the high arts of poetry, weaving and music. Due to the Tutsi's status as a dominant minority vis-a-vis the Hutu farmers and the other local inhabitants, this relationship has been likened to that between lords and serfs in feudal Europe.[31]

According to Fage (2013), the Tutsi are serologically related to Bantu and Nilotic populations. This in turn rules out a possible Cushitic origin for the founding Tutsi-Hima ruling class in the lacustrine kingdoms. However, the royal burial customs of the latter kingdoms are quite similar to those practiced by the former Cushitic Sidama states in the southern Gibe region of Ethiopia. By contrast, Bantu populations to the north of the Tutsi-Hima in Kenya were until modern times essentially without a king, while there were a number of Bantu kingdoms to the south of the Tutsi-Hima in Tanzania, all of which shared the Tutsi-Hima's chieftaincy pattern. Since the Cushitic Sidama kingdoms interacted with Nilotic groups, Fage thus proposes that the Tutsi may have descended from one such migrating Nilotic population. The Tutsis' Nilotic ancestors would thereby in earlier times have served as cultural intermediaries, adopting some monarchical traditions from adjacent Cushitic kingdoms and subsequently taking those borrowed customs south with them when they first settled amongst Bantu autochthones in the Great Lakes area.[31]

However, little difference can be ascertained between the cultures today of the Tutsi and Hutu; both groups speak the same Bantu language. The rate of intermarriage between the two groups was traditionally very high, and relations were amicable until the 20th century. Many scholars have concluded that the determination of Tutsi was and is mainly an expression of class or caste, rather than ethnicity.

As noted above, DNA studies show clearly that the peoples are more closely related to each other than to faraway groups.

Congolese Tutsi

There are essentially two groups of Tutsi in the Congo (DRC). There is the Banyamulenge, who live in the southern tip of South Kivu. They are descendants of migrating Rwandan, Burundian and Tanzanian pastoralists. And secondly there are Tutsi in North Kivu and Kalehe in South Kivu – being part of the Banyarwanda (Hutu and Tutsi) community. These are not Banyamulenge. Some of these Banyarwanda are descendants of people that lived long before colonial rule in Rutshuru – on what is currently Congolese territory. Others migrated or were "transplanted" by the Belgian colonists from Rutshuru or from Rwanda and mostly settled in Masisi in North Kivu and Kalehe in South Kivu.

Notable people

References

- https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/congolese-tutsi-troubled-drc-equation

- Trombetta, Beniamino; D’Atanasio, Eugenia; Massaia, Andrea; Ippoliti, Marco; Coppa, Alfredo; Candilio, Francesca; Coia, Valentina; Russo, Gianluca; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel (24 June 2015). "Phylogeographic Refinement and Large Scale Genotyping of Human Y Chromosome Haplogroup E Provide New Insights into the Dispersal of Early Pastoralists in the African Continent". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (7): 1940–1950. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv118. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 4524485. PMID 26108492.

- "Tutsi". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Watusi definition and meaning – Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- Gourevitch, Philip (2000). We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families (Reprint ed.). London; New York, N.Y.: Picador. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-330-37120-9.

- Leatherman, Janie (1999). Breaking Cycles of Violence: Conflict Prevention in Intrastate Crises. Kumarian. p. 142. ISBN 9781565490918.

- Jenkins, Dr. Orville Boyd. "Tutsi, Hutu and Hima – Cultural Background in Rwanda". orvillejenkins.com.

- International Institute of African Languages and Cultures, Africa, Volume 76, (Oxford University Press., 2006), pg 135.

- Josh Kron, "Shooting star of the continent", Haaretz, 14 September 2010, accessed 14 September 2010

- "Tutsi | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Philip Gourevitch,We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families. 1998.

- "'Indangamuntu 1994: Ten years ago in Rwanda this ID Card cost a woman her life' by Jim Fussell". www.preventgenocide.org.

- Luis, J. R.; et al. (2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (3): 532–544. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

- https://yfull.com/tree/E-M293/

- Henn, B; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of a pastoralist migration through Tanzania to southern Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (31): 10693–8. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510693H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801184105. PMC 2504844. PMID 18678889.

- "E-Y5861 YTree". yfull.com. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Fornarino, Simona; Pala, Maria; Battaglia, Vincenza; et al. (2009). "Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome diversity of the Tharus (Nepal): a reservoir of genetic variation". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009 (9): 154. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-154. PMC 2720951. PMID 19573232.

- Joseph C. Miller (ed.), New Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 2, Dakar-Hydrology, Charles Scribner's Sons (publisher).

- Michael C. Campbell, Sarah A. Tishkoff, African Genetic Diversity: Implications for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics Vol. 9 (Volume publication date September 2008)(doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164258)http://www.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2009/04/30/1172257.DC1/Tishkoff.SOM.pdf

- "The Rise and Fall Of the Watusi". 23 February 1964 – via NYTimes.com.

- Berg, Irwin M. "Jews in Central Africa". Kulanu Highlights. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- Michael Bowen, Passing by;: The United States and genocide in Burundi, 1972, (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1973), p. 49

- René Lemarchand, Selective genocide in Burundi (Report – Minority Rights Group; no. 20, 1974)

- Rene Lemarchand, Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide (New York: Woodrow Wilson Center and Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Edward L. Nyankanzi, Genocide: Rwanda and Burundi (Schenkman Books, 1998)

- Christian P. Scherrer, Genocide and crisis in Central Africa: conflict roots, mass violence, and regional war; foreword by Robert Melson. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2002

- Weissman, Stephen R."Preventing Genocide in Burundi Lessons from International Diplomacy Archived 11 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine", United States Institute of Peace

- "Google Sites" (PDF). allan.stam.googlepages.com.

- International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report, Part III: Investigation of the Assassination. Conclusions at USIP.org Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Totten, p. 331

- International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi (2002)

- Fage, John (23 October 2013). A History of Africa. Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 978-1317797272. Retrieved 8 January 2015.