Benue–Congo languages

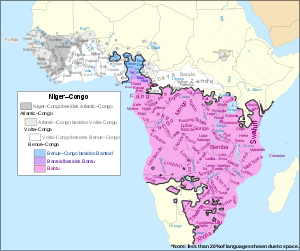

Benue–Congo (sometimes called East Benue–Congo) is a major subdivision of the Niger–Congo language family which covers most of Sub-Saharan Africa. It consists of two main branches:

- the Central Nigerian (or Platoid) languages, spoken mostly in Nigeria

- the Bantoid–Cross languages, spoken in Nigeria, Cameroon and most of Sub-Saharan Africa, since they contain the Bantu languages (through the Southern Bantoid branch).

| Benue–Congo | |

|---|---|

| East Benue–Congo | |

| Geographic distribution | Africa, from Nigeria eastwards and southwards |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | benu1247[1] |

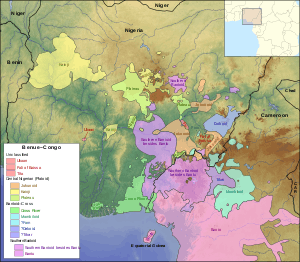

The Benue–Congo languages shown within the Niger–Congo language family. Non-Benue–Congo languages are greyscale. | |

Subdivisions

Central Nigerian (or Platoid) contains the Plateau, Jukunoid and Kainji families, and Bantoid–Cross combines the Bantoid and Cross River groups.

Bantoid is only a collective term for every subfamily of Bantoid–Cross except Cross River, and this is no longer seen as forming a valid branch, however one of the subfamilies, Southern Bantoid, is still considered valid. It is Southern Bantoid which contains the Bantu languages, which are spoken across most of Sub-Saharan Africa. This makes Benue–Congo one of the largest subdivisions of the Niger–Congo language family, both in number of languages, of which Ethnologue counts 976 (2017), and in speakers, numbering perhaps 350 million. Benue–Congo also includes a few minor isolates in the Nigeria–Cameroon region, but their exact relationship is uncertain.

The neighbouring Volta–Niger branch of Nigeria and Benin is sometimes called "West Benue–Congo", but it does not form a united branch with Benue–Congo. When Benue–Congo was first proposed by Joseph Greenberg (1963), it included Volta–Niger (as West Benue–Congo); the boundary between Volta–Niger and Kwa has been repeatedly debated. Blench (2012) states that if Benue–Congo is taken to be "the noun-class languages east and north of the Niger", it is likely to be a valid group, though no demonstration of this has been made in print.[2]

The branches of the Benue–Congo family are thought to be as follows:

- Bantoid–Cross languages

- Central Nigerian languages, also known as Platoid

Ukaan is also related to Benue–Congo; Roger Blench suspects it might be either the most divergent (East) Benue–Congo language or the closest relative to Benue–Congo.

Fali of Baissa and Tita are also Benue–Congo but are otherwise unclassified.

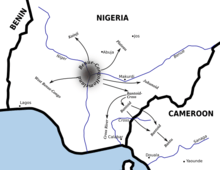

Branches and locations (Nigeria)

Below is a list of major Benue–Congo branches and their primary locations (centres of diversity) within Nigeria based on Blench (2019).[4]

| Branch | Primary locations |

|---|---|

| Cross River | Cross River, Akwa Ibom, and Rivers States |

| Bendi | Obudu and Ogoja LGAs, Cross River State |

| Mambiloid | Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Dakoid | Mayo Belwa LGA, Taraba State and adjacent areas |

| Jukunoid | Taraba State |

| Yukubenic | Takum LGA, Taraba State |

| Kainji | Kauru LGA, Kaduna State and Bassa LGA, Plateau State; Kainji Lake area |

| Plateau | Plateau, Kaduna, and Nasarawa States |

| Tivoid | Obudu LGA, Cross River State and Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Beboid | Takum LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Ekoid | Ikom and Ogoja LGAs, Cross River State; Cameroon |

| Grassfields | Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Jarawan | Bauchi, Plateau, Adamawa, and Taraba States |

Comparative vocabulary

Sample basic vocabulary for reconstructed proto-languages of different Benue-Congo branches:

| Branch | Language | eye | ear | nose | tooth | tongue | mouth | blood | bone | tree | water | eat | name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benue-Congo | Proto-Benue-Congo[5] | *-lito | *-tuŋi | *-zua | *-nini, *-nino; *-sana; *-gaŋgo | *-lemi; *-lake | *-zi; *-luŋ | *-kupe | *-titi; *-kwon | *-izi; *-ni | *-zina | ||

| Kainji | Proto-Northern Jos[6] | **iji (lì-/à-) | *toŋ (ù-/tì-) | *nyimu (bì-/ì-) | *ʔini (lì-/à-) | *lelem (lì-/à-) | *nua (ù-/tì-) | *nyì(aw) (mà-) | *ti (with reduplication) (ù-/tì-) | *nyi (mà-) | *lia | *ji(a) (lì-/sì-) | |

| Plateau | Proto-Jukunoid[7] | *giP (ri-/a-) | *tóŋ (ku-/a-) | *wíǹ (ri-/a-) | *baŋ (ku-/a-); *gyín (ri-/a-) | *déma (ri-/a-) | *ndut (u-/i-) | *yíŋ (ma-) | *kup (ku-/a-) | *kun (ku-/i-) | *mbyed | *dyi | *gyin (ri-/a-) |

| Plateau | Proto-Kagoro[8] | *-gi | *-two | *nii[ŋ] | *-dyam | *-nu[ŋ] | *-suok | *-kup | *-kwan | *-sii | |||

| Plateau | Proto-Jaba[8] | *gu-su | *gu-to[ŋ] | *-gi[ŋ] | *ga-lem | *ga-nyu | *ba-zi | *gu-kup | |||||

| Plateau | Proto-Beromic[8] | *-gis | *-toŋ | *-ɣiŋ | *-lyam | *-nu | *nì-ji | *-kup | *-kon | *-sii | |||

| Plateau | Proto-Ninzic[8] | *ki-sị́ | *ku-tóŋ | *ki-Nyin / *-Nyir | *ì-rem | *-nuŋ / *-n[y]uŋ | *ma-ɣì | *kù-kụp | *ù-kon | *a-ma-sit | |||

| Cross | Proto-Upper Cross[9] | *dyèná | *-ttóŋ(ì) | *dyòná | *-ttân | *-dák | *-mà | *-dè; *-yìŋ | *-kúpà | *-tté | *-nì | *dyá | *-dínà |

| Cross | Proto-Lower Cross[10] | *ɛ́-ɲɛ̀n / *a- | *ú-tɔ́ŋ / *a- | *í-búkó | *é-dɛ̀t / *a- | *ɛ́-lɛ́mɛ̀ / *a- | *í-núà | *-ɟìːp | *ɔ́-kpɔ́ | *é-tíé | *ˊ-mɔ́ːŋ | *líá | *ɛ́-ɟɛ́n |

| Cross | Proto-Ogoni[11] | *adɛ́ɛ̃ | *ɔ̀tɔ́̃ | *m̀ bĩɔ́̃ | *àdáNa | *àdídɛ́Nɛ́ | *m̀ miNi, *m̀ muNu | *ákpogó | *èté | m̀ mṹṹ | *dè | *àbée | |

| Bantoid | Proto-Grassfields[12] | *Ít` | *túŋ-li | *L(u)Í` | *sòŋ´ | *lím` | *cùl` | *lém`; *cÌ´ | *gÚp; *kúi(n)´ | *tí´ | *LÍb; *kÌ´; *mò´ | *lÍa | *lÍn`; *kúm |

| Bantoid | Proto-Ring[13] | *túɛ̀ | *túndé | *dúì, *tɔ́ŋ | *túŋɔ̀, *góìk | *dɔ́mì, *dídè | *dúɔ̀ | *dúŋá, *káŋù | *gúpɛ́ | *kák`, *tíɛ́ | *múɔ̀ | *dúɛ̀ | *dítɔ́, *gíd' |

| Bantu | Proto-Bantu[14] | *i=jíco | *kʊ=tʊ́i | *i=jʊ́lʊ | *i=jíno; *i=gego | *lʊ=lɪ́mi | *ka=nʊa; *mʊ=lomo | *ma=gilá; *=gil-a; *ma=gadí; *=gadí; *mʊ=lopa; *ma=ɲínga | *i=kúpa | *mʊ=tɪ́ | *ma=jíjɪ; *i=diba (HH?) | *=lɪ́ -a | *i=jína |

| Bantu | Swahili | jicho | sikio | pua | jino | ulimi | kinywa | damu (Ar.) | mfupa | mti | maji | la | jina |

See also

- List of Proto-Benue-Congo reconstructions (Wiktionary)

- Systematic graphic of the Niger–Congo languages with numbers of speakers

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Benue–Congo". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Roger Blench, Niger-Congo: an alternative view

- Watters JR (2018). Watters, John R (eds.). East Benue-Congo: Nouns, pronouns, and verbs (pdf). Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1314306. ISBN 978-3-96110-100-9.

- Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- de wolf, Paul. 1971. The Noun-Class System of Proto-Benue-Congo. Janua Linguarum. Series Practica 167. The Hague: Mouton.

- Shimizu, Kiyoshi, 1982. Die North-Jos Gruppe der Plateau=Spreachen Nigerias. Afrika und Übersee, vol. 65.2 (1982), 161-210.

- Shimizu, Kiyoshi. 1980. Comparative Jukunoid, 3 vols. (Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien 7–9. Beiträge zur Afrikanistik 5–7). Vienna: Afro-Pub.

- Gerhardt, Ludwig. 1983. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Sprachen des Nigerianischen Plateaus (Afrikanistische Forschungen 9). Glückstadt: J. J. Augustin.

- Dimmendaal, Gerrit J. 1978. The Consonants of Proto-Upper Cross and their Implications for the Classification of the Upper Cross Languages. Leiden: Leiden University.

- Connell, Bruce. n.d. Comparative Lower Cross wordlist. Unpublished manuscript.

- Blench, Roger and Kay Williamson. 2008. The Ogoni languages: comparative word list and historical reconstructions.

- Hyman, L.M. 1979. Index of Proto-Grassfields Bantu roots. Ms. U.S.C.; CBOLD; accessed from Comparalex.

- Paulin, Pascale. 1995. Etude comparative des langues du groupe Ring: langues Grassfields de l'ouest, Cameroun. MA thesis, Université Lumière Lyon 2.

- Schadeberg, Thilo C. 2003. Historical linguistics. In Derek Nurse and Gérard Philippson (eds.), The Bantu languages. (Routledge language family series 4. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-700-71134-5

- Wolf, Paul Polydoor de (1971) The Noun Class System of Proto-Benue–Congo (Thesis, Leiden University). The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

- Williamson, Kay (1989) 'Benue–Congo Overview', pp. 248–274 in Bendor-Samuel, John & Rhonda L. Hartell (eds.) The Niger–Congo Languages – A classification and description of Africa's largest language family. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

External links

- ComparaLex, database with Benue-Congo word lists

- Web resources for the Benue–Congo languages

- Journal of West African Languages: Benue-Congo

- Proto-Benue-Congo Swadesh list (de Wolf 1971)