Torvosaurus

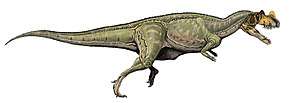

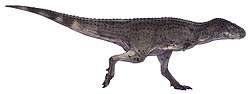

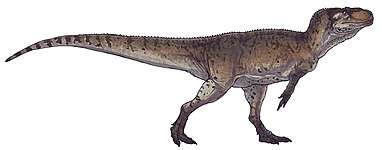

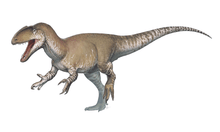

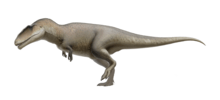

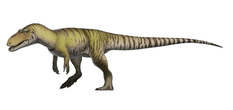

Torvosaurus (/ˌtɔːrvoʊˈsɔːrəs/) is a genus of carnivorous megalosauroid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 153 to 148 million years ago during the Late Jurassic Period (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) in what is now Colorado and Portugal. It contains two currently recognized species, Torvosaurus tanneri and Torvosaurus gurneyi.

| Torvosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted T. tanneri skeletal reconstruction, Museum of Ancient Life | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Megalosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Megalosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Torvosaurus Galton & Jensen, 1979 |

| Type species | |

| †Torvosaurus tanneri Galton & Jensen, 1979 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

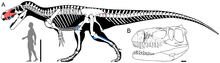

In 1979 the type species Torvosaurus tanneri was named: it was a large, heavily built, bipedal carnivore, that could grow to a length of about 10 m (33 ft). T. tanneri was among the largest carnivores of its time, together with Epanterias and Saurophaganax (which could be both synonyms of Allosaurus). Specimens referred to Torvosaurus gurneyi were initially claimed to be up to twelve metres long, but later shown to be smaller.[1] Based on bone morphology Torvosaurus is thought to have had short but very powerful arms.

Discovery

Fossilized remains of Torvosaurus have been found in North America and Portugal. In 1971, Vivian Jones, of Delta, Colorado (USA), in the Calico Gulch Quarry in Moffat County, discovered a single gigantic thumb claw of a theropod. This was shown to James Alvin Jensen, a collector working for Brigham Young University. In an effort to discover comparable fossils, Vivian's husband Daniel Eddie Jones directed Jensen to the Dry Mesa Quarry, where abundant gigantic theropod bones, together with Supersaurus remains, proved present in rocks of the Morrison Formation. From 1972 onwards the site was excavated by Jensen and Kenneth Stadtman. The type species Torvosaurus tanneri was named and described in 1979 by Peter Malcolm Galton and Jensen.[2] The genus name Torvosaurus derives from the Latin word torvus, meaning "savage", and the Greek word sauros (σαυρος), meaning "lizard".[3] The specific name tanneri, is named after first counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Nathan Eldon Tanner.

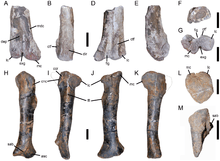

In 1985, Jensen could report a considerable amount of additional material, among it the first skull elements.[4] The fossils from Colorado were further described by Brooks Britt in 1991.[5] The holotype BYU 2002 originally consisted of upper arm bones (humeri) and lower arm bones (radii and ulnae). The paratypes included some back bones, hip bones, and hand bones.[2] When the material described in 1985 is added, the main missing elements are the shoulder girdle and the thighbone.[5] The original thumb claw, specimen BYUVP 2020, was only provisionally referred as it had been found in a site 195 kilometres away from the Dry Mesa Quarry.[2] The holotype and paratypes represented at least three individuals: two adults and a juvenile.[5] In 1991 Britt concluded that there was no proof that the front limbs of the holotype were associated and chose the left humerus as the lectotype.[5] Several single bones and teeth found in other American sites have been referred to Torvosaurus.[5]

In 1992, fossils of a large theropod found at Como Bluff in Wyoming, containing skull, shoulder girdle, pelvis and rib elements, were named by Robert T. Bakker et al. as the species Edmarka rex. Bakker et al were impressed with the size of Edmarka, noting that it "would rival T. rex in total length," and viewing this approximate size as "a natural ceiling for dinosaurian meat-eaters."[6] This was often considered a junior synonym of Torvosaurus.[7] The same site has rendered comparable remains for which the nomen nudum Brontoraptor has been used.[8][9] Most researchers now regard both specimens as belonging to Torvosaurus tanneri.[1]

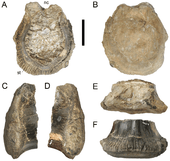

In 2000, material from Portugal was referred to a Torvosaurus sp. by Octávio Mateus and Miguel Telles Antunes.[10] In 2006 fossils from the Portuguese Lourinhã Formation were referred to Torvosaurus tanneri.[11] In 2012, however, Matthew Carrano e.a. concluded that this material could not be more precisely determined than a Torvosaurus sp.[7] In 2013 eggs and embryos were reported from Portugal, referred to Torvosaurus.[12] The species from Portugal was named T. gurneyi in honor of James Gurney in 2014, the creator of the Dinotopia series of books. It is the largest theropod known from Europe.[1] It was the morphological distinctiveness of the holotype maxilla ML1100 that led to the naming of the Portuguese species.[1]

Description

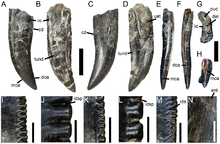

Torvosaurus was a very large predator, with an estimated maximum body length of 10 m (33 ft) and mass of 3.6–4.5 tonnes (4–5 short tons) for both T. tanneri and T. gurneyi,[1][2][13] making Torvosaurus among the largest land carnivores of the Jurassic. Thomas Holtz estimated it at 12 meters (39 feet).[14] Claims have been made indicating even larger sizes. The synonymous Edmarka rex was named thus because it was assumed to rival Tyrannosaurus rex in length. Likewise "Brontoraptor" was supposed to be a torvosaur of gigantic size.[15] The T. gurneyi specimens from Portugal initially prompted larger size estimates to be made. In 2006 a lower end of a thighbone, specimen ML 632, was referred to Torvosaurus sp. and later to T. gurneyi. This specimen was initially stated to indicate a length of 11 m (36 ft). Applying the extrapolation method of J.F. Anderson, correlating mammal weights to their femur circumference, resulted in a weight of 1930 kilogrammes. However, revised estimates performed in 2014 suggested a slightly smaller total body size for this specimen, of about 10 m (33 ft).[1] Among the differentiating features between T. gurneyi and T. tanneri are the number of teeth and the size and shape of the mouth. While the upper jaw of T. tanneri has more than 11 teeth, that of T. gurneyi has less.[1]

Torvosaurus had an elongated, narrow snout, with a kink in its profile just above the large nostrils. The frontmost snout bone, the praemaxilla, bore three rather flat teeth oriented somewhat outwards with the front edge of the teeth crown overlapping the outer side of the rear edge of the preceding crown. The maxilla was tall and bore at least eleven rather long teeth. The antorbital fenestra was relatively short. The lacrimal bone had a distinctive lacrimal horn on top; its lower end was broad in side view. The eye socket was tall with a pointed lower end. The jugal was long and transversely thin. The lower front side of the quadrate bone was hollowed out by a tear-shaped depression, the contact surface with the quadratojugal. Both the neck vertebrae and the front dorsal vertebrae had relatively flexible ball-in-socket joints. The balls, on the front side of the vertebral centra, had a wide rim, a condition by Britt likened to a Derby hat. The tail base was stiffened in the vertical plane by high and in side view wide neural spines. The upper arm was robust; the lower arm robust but short. Whether the thumb claw was especially enlarged, is uncertain. In the pelvis, the ilium resembled that of Megalosaurus and had a tall, short, front blade and a longer pointed rear blade. The pelvis as a whole was massively built, with the bone skirts between the pubic bones and the ischia contacting each other and forming a vaulted closed underside.[5]

Systematics and classification

When first described in 1979 by Galton and Jensen,[2] Torvosaurus was classified as a megalosaurid, which is the current consensus.[7] It was later assigned to Carnosauria by Ralph Molnar et al. in 1990,[16] and to a basal position in Spinosauroidea by Oliver Walter Mischa Rauhut in 2003[17] and to a very basal position in the Tetanurae by Thomas Holtz in 1994;[18] all these assignments are not supported by present phylogenetic analysis.[7] In 1985, Jensen assigned Torvosaurus a family of its own, the Torvosauridae.[4] Despite support for this concept by Paul Sereno[19] and Mateus,[11] it seems redundant as Torvosaurus is closely related to, and perhaps the sister species of, the earlier Megalosaurus within a Megalosaurinae.[7] However, Torvosauridae may be used as an alternative name for Megalosauridae if Megalosaurus is considered an indeterminable nomen dubium.[20] Though a close relative of Megalosaurus, Torvosaurus is seemingly more advanced or apomorphic. Torvosaurus's larger clade, the Megalosauridae, is most commonly held as a basal branch of the Tetanurae, and considered less derived than carnosaurs or coelurosaurs, and likely related to the spinosaurids.[7]

The following is a cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Carrano, Benson & Sampson (2012), showing the relationships of Torvosaurus:[7]

| Megalosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distinguishing anatomical features

According to Carrano et al. (2012), Torvosaurus can be distinguished based on the following characteristics:[21]

- the presence of a very shallow maxillary fossa (it lacks a fenestra maxillaris piercing the bone wall)

- the presence of fused interdental plates

- the pneumatic fossae in the posterior dorsal and the anterior caudal vertebrae centra are expanded, forming enlarged, deep openings

- the puboischiadic plate is highly ossified (the paired bony plates, of both sides, connect and close off the entire underside of the pelvis, a very basal trait that Galton & Jensen saw as an indication that Theropoda was polyphyletic, the Carnosauria having independently evolved from carnivorous Prosauropoda)[2]

- a distal expansion of the ischium shaft with a prominent lateral midline crest and an oval outline when examined in lateral view

- the cervical vertebrae are opisthocoelous with a pronounced flat rim around the, anterior, ball (according to Rauhut, 2000)

- a (transverse) fenestra is situated in the neural arch of the dorsal vertebrae in front of the hyposphene (according to Rauhut, 2000)[22]

Paleobiology

Eggs and ovipary

The careful study of fossil dinosaur embryos provides researchers with information about the transformation of the embryo over time, the different developmental pathways present in dinosaur lineages, dinosaur reproductive behavior, and dinosaur parental care.[23][24][25]

In 2013, Araújo et al. announced the discovery of specimen ML1188, a clutch of crushed dinosaur eggs and embryonic material attributed to Torvosaurus. This discovery further supports the hypothesis that large theropod dinosaurs were oviparous, meaning that they laid eggs and hence that embryonic development occurred outside the body of female dinosaurs. This discovery was made in 2005 by the Dutch amateur fossil-hunter Aart Walen at the Lourinhã Formation in Western Portugal, in fluvial overbank sediments that are considered to be from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic Period, approximately 152 to 145 million years ago. This discovery is significant paleontologically for a number of reasons: (a) these are the most primitive dinosaur embryos known; (b) these are the only basal theropod embryos known; (c) fossilized eggs and embryos are rarely found together; (d) it represents the first evidence of a one-layered eggshell for theropod dinosaurs; and (e) it allows researchers to link a new eggshell morphology to the osteology of a particular group of theropod dinosaurs.[12] The specimen is housed at the Museu da Lourinhã, in Portugal. As the eggs were abandoned due to unknown circumstances, it is not known if Torvosaurus provided parental care to its eggs and young or abandoned them shortly after laying.[26]

Paleoecology

Provenance and occurrence

The type specimen of Torvosaurus tanneri BYU 2002 was recovered in the Dry Mesa Quarry of the Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation, in Montrose County, Colorado. The specimen was collected by James A. Jensen and Kenneth Stadtman in 1972 in medium-grained, coarse sandstone that was deposited during the Tithonian and Kimmeridgian stages of the Jurassic period, approximately 153 to 148 million years ago.[27] This specimen is housed in the collection of Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

Fauna and habitat in North America

Studies suggest that the paleoenvironment of this section of the Morrison Formation included rivers that flowed from the west into a basin that contained a giant, saline alkaline lake and there were extensive wetlands in the vicinity. The Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry of western Colorado yields one of the most diverse Upper Jurassic vertebrate assemblages in the world.[28] The Dry Mesa Quarry has produced the remains of the sauropods Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Barosaurus, Supersaurus, Dystylosaurus and Camarasaurus, the iguanodonts Camptosaurus and Dryosaurus, and the theropods Allosaurus, Tanycolagreus, Koparion, Stokesosaurus, Ceratosaurus and Ornitholestes, as well as Othnielosaurus, Gargoyleosaurus and Stegosaurus.[29]

The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Animal fossils discovered include bivalves, snails, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, amphibians, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial (like Hoplosuchus) and aquatic crocodylomorphans, cotylosaurs, several species of pterosaurs like Harpactognathus, and early mammals, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts.[29]

Fauna and habitat in Europe

The Lourinhã Formation is also Kimmeridgian-Tithonian in age. The environment is coastal, and therefore has a strong marine influence. Its flora and fauna are very similar to the Morrison. Torvosaurus appears to be the top predator here. It lived alongside European species of Allosaurus (A. europaeus), Ceratosaurus, Stegosaurus and presumably Camptosaurus. Theropod Lourinhanosaurus also stalked the area. Lusotitan was the largest sauropod in the region, while the diplodocids Dinheirosaurus and Lourinhasaurus were also present. Dacentrurus and Miragaia were both stegosaurs, while Dracopelta was an ankylosaurian. Draconyx was an iguanodontid related to Camptosaurus. Due to the marine nature of the Lourinhã Formation, sharks, plesiochelyid turtles, and teleosaurid crocodyliforms are also present.[30]

Coexistence with other large carnivores

Torvosaurus coexisted with other large theropods such as Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Saurophaganax in the United States, and Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Lourinhanosaurus in Portugal. The three appear to have had different ecological niches, based on anatomy and the location of fossils. Torvosaurus and Ceratosaurus may have preferred to be active around waterways, and had lower, more sinuous, bodies that would have given them an advantage in forest and underbrush terrains, whereas Allosaurus had shorter bodies, longer legs, were faster but less maneuverable, and seem to have preferred dry floodplains.[31] Allosaurus was itself a potential food item to other carnivores, as illustrated by an Allosaurus pubic foot marked by the teeth of another theropod, probably Ceratosaurus or Torvosaurus. The location of the bone in the body (along the bottom margin of the torso and partially shielded by the legs), and the fact that it was among the most massive in the skeleton, indicates that the Allosaurus was being scavenged.[32]

References

- Hendrickx, C.; Mateus, O. (2014). Evans, Alistair Robert (ed.). "Torvosaurus gurneyi n. sp., the Largest Terrestrial Predator from Europe, and a Proposed Terminology of the Maxilla Anatomy in Nonavian Theropods". PLoS ONE. 9 (3): e88905. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988905H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088905. PMC 3943790. PMID 24598585.

- P. M. Galton and J. A. Jensen. 1979. A new large theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Colorado. Brigham Young University Geology Studies 26(1):1-12

- Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Jensen, J.A., 1985, "Uncompahgre dinosaur fauna: A preliminary report", Great Basin Naturalist, 45: 710-720

- Britt, B., 1991, "Theropods of Dry Mesa Quarry (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic), Colorado, with emphasis on the osteology of Torvosaurus tanneri", Brigham Young University Geology Studies 37: 1-72

- Bakker, R.T., Siegwarth, J., Kralis, D. & Filla, J., 1992, "Edmarka rex, a new, gigantic theropod dinosaur from the middle Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic of the Como Bluff outcrop region", Hunteria, 2(9): 1–24

- Carrano, M. T.; Benson, R. B. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927

- Redman, P.D., 1995, Paleo Horizons, Winter Issue

- Siegwarth, J., Linbeck, R., Bakker, R. and Southwell, B. (1996). Giant carnivorous dinosaurs of the family Megalosauridae. Hunteria 3:1-77.

- Mateus, O., & Antunes, M. T. (2000). Torvosaurus sp.(Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the late Jurassic of Portugal. In I Congresso Ibérico de Paleontologia/XVI Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Paleontología (pp. 115-117)

- Mateus, O., Walen, A., and Antunes, M.T. (2006). "The large theropod fauna of the Lourinha Formation (Portugal) and its similarity to that of the Morrison Formation, with a description of a new species of Allosaurus." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36.

- Ricardo Araújo, Rui Castanhinha, Rui M. S. Martins, Octávio Mateus, Christophe Hendrickx, F. Beckmann, N. Schell & L. C. Alves (2013) Filling the gaps of dinosaur eggshell phylogeny: Late Jurassic Theropod clutch with embryos from Portugal. Scientific Reports 3 : Article number: 1924 doi:10.1038/srep01924

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster. p. 282. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.

- Holtz, Thomas R. (2012). "Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages" (PDF).

- Siegwarth, J., Linbeck, R., Bakker, R. and Southwell, B., 1996, "Giant carnivorous dinosaurs of the family Megalosauridae", Hunteria 3: 1-77

- R. E. Molnar, S. M. Kurzanov, and Z. Dong. 1990. "Carnosauria". In: D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmólska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley

- O. W. M. Rauhut. 2003. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 69:1-213

- T.R. Holtz, 1994, "The phylogenetic position of the Tyrannosauridae: implications for theropod systematics", Journal of Paleontology 68(5): 1100-1117

- P.C. Sereno, J.A. Wilson, H.C.E. Larsson, D.B. Dutheil, and H.-D. Sues, 1994, "Early Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Sahara", Science 266(5183): 267-271

- P.C. Sereno, 1998, "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 210(1): 41-83

- Carrano, Benson and Sampson, 2012. The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10(2), 211-300

- Rauhut, 2000. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropods (Dinosauria, Saurischia). Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. Bristol [U.K.], 1-440.

- Long, J. A. & McNamara, K. J. Heterochrony: The key to dinosaur evolution. in The Dinofest International (Wolberg, D.L., Stump, E. & Rosenberg, G. D., eds.) 113–123 ( Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil. , 1997).

- Balanoff, A. M., Norell, M. A., Grellet-Tinner, G. & Lewin, M. R. Digital preparation of a probable neoceratopsian preserved within an egg, with comments on microstructural anatomy of ornithischian eggshells. Naturwissenschaften 95 , 493–500 (2008).

- Varricchio, D. J. et al., 2008. Avian paternal care had dinosaur origin. Science 322 , 1826– 1828.

- "A rare find: Abandoned dinosaur nests with eggshells".

- J. A. Jensen and J. H. Ostrom. 1977. A second Jurassic pterosaur from North America. Journal of Paleontology 51(4):867-870

- Richmond, D.R. and Morris, T.H., 1999, Stratigraphy and cataclysmic deposition of the Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry, Mesa County, Colorado, in Carpenter, K., Kirkland, J., and Chure, D., eds., The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study, Modern Geology v. 22, no. 1-4, pp. 121–143.

- Chure, Daniel J.; Litwin, Ron; Hasiotis, Stephen T.; Evanoff, Emmett; Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- OCTÁVIO MATEUS LATE JURASSIC DINOSAURS FROM THE MORRISON FORMATION (USA), THE LOURINHÃ AND ALCOBAÇA FORMATIONS (PORTUGAL), AND THE TENDAGURU BEDS (TANZANIA): A COMPARISON Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S. G. R.M., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36.

- Bakker, Robert T.; Bir, Gary (2004). "Dinosaur crime scene investigations: theropod behavior at Como Bluff, Wyoming, and the evolution of birdness". In Currie, Philip J.; Koppelhus, Eva B.; Shugar, Martin A.; Wright, Joanna L. (eds.). Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 301–342. ISBN 978-0-253-34373-4.

- Chure, Daniel J. (2000). "Prey bone utilization by predatory dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of North America, with comments on prey bone use by dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 227–232. ISSN 0871-5424.