Alvarezsauroidea

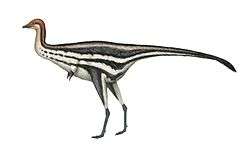

Alvarezsauroidea is a group of small maniraptoran dinosaurs. Alvarezsauroidea, Alvarezsauridae, and Alvarezsauria are named for the historian Gregorio Álvarez, not the more familiar physicist Luis Alvarez, who proposed that the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event was caused by an impact event. The group was first formally proposed by Choiniere and colleagues in 2010, to contain the family Alvarezsauridae and non-alvarezsaurid alvarezsauroids, such as Haplocheirus,[1] which is the basalmost of the Alvarezsauroidea (from the Late Jurassic, Asia). The discovery of Haplocheirus extended the stratigraphic evidence for the group Alvarezsauroidea about 63 million years further in the past. The division of Alvarezsauroidea into the Alvarezsauridae and the non-alvarezsaurid alvarezsauroids is based on differences in their morphology, especially in their hand morphology.

| Alvarezsauroidea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of a Mononykus olecranus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Maniraptora |

| Clade: | †Alvarezsauria Bonaparte, 1991 |

| Superfamily: | †Alvarezsauroidea Bonaparte, 1991 |

| Type species | |

| †Alvarezsaurus calvoi Bonaparte, 1991 | |

| Subgroups | |

Introduction

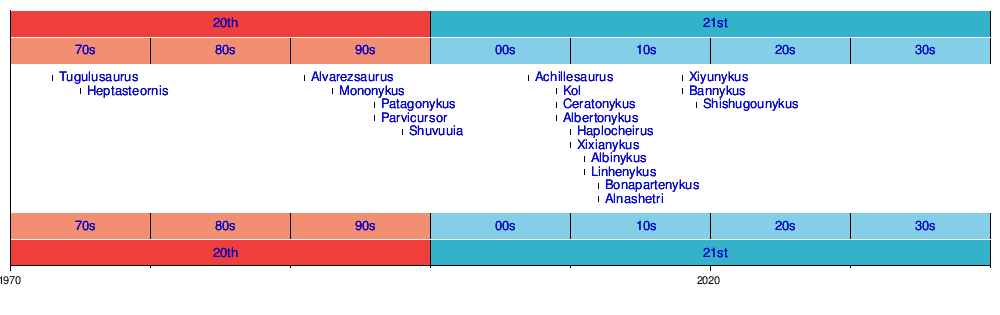

The first fossil alvarezsauroids were recognized in the 1990s. Since then, the number of specimens found has dramatically increased. Most of the recent alvarezsauroids are found in China, but they are also known from the Americas and Europe.[1] They existed from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous. The basalmost and oldest alvarezsauroid of the Chinese alvarezsaurs is from the Shishugou Formation in Xinjiang (earliest Late Jurassic). Additionally, two derived members of the derived alvarezsaur group Parvicursorinae are known from the Inner Mongolia and Henan (Late Cretaceous).

The size of the derived members of Alvarezsauroidea range between 0.5 and 2 m (1 ft 8 in and 6 ft 7 in), but some members may have been larger.[2] Haplocheirus, for example, was the largest member of the Alvarezsauroidea. Because of the size of Haplocheirus and its basal phylogenetic position, a pattern of miniaturization for the Alvarezsauroidea is suggested. Miniaturizations are very rare in dinosaurs, but convergently evolved in Paraves.[1]

Classification

The phylogenetic placement of Alvarezsauroidea is still unclear. At first, they were interpreted as a sister group of Avialae (birds) or nested within the group Avialae [1] and considered to be flightless birds,[3] because they share many morphological characteristics with them, such as a loosely sutured skull, a keeled sternum, fused wrist elements, and a posteriorly directed pubis.[1] But this association was reevaluated after the discovery of the primitive forms like Haplocheirus, Patagonykus and Alvarezsaurus, which do not show all bird-like features as the first discovered species Mononykus and Shuvuuia.[4] This shows that bird-like characteristics were developed multiple times within the Maniraptora. Furthermore, the Alvarezsauroidea had simplified homogenous dentition, convergent with that of some extant insectivorous mammals. More recently, they have been placed within the Coelurosauria basal to the Maniraptora or as a sister taxa of Ornithomimosauria within the Ornithomimiformes.

The cladogram below is based on Choniere et al. (2010).[1]

| Alvarezsauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Geographical distribution

At first, alvarezsauroids were thought to have been originated in South America. However, the discovery of Haplocheirus, and its basal phylogenetic position, as well as its early temporal position, suggests they derived in Asia rather than South America. Xu et al. (2011) suggested that at least three dispersal events of alvarezsauroids took place; one from Asia to Gondwana, one from Gondwana to Asia, and one from Asia to North America. This hypothesis is consistent with faunal interchanges.[3] On the other hand, some theropod groups are inconsistent with this hypothesis. Xu et al. (2013) used event−based tree−fitting to perform a quantitative analysis of alvarezsauroid biogeography.[5] Their results showed an absence of statistical support for previous biogeographic hypotheses that favour pure vicariance or pure dispersal scenarios as explanations for the distributions of alvarezsauroids across South America, North America and Asia. They instead found that statistically significant biogeographic reconstructions suggest a dominant role for sympatric events (“within area” ones), combined with a mix of vicariance, dispersal and regional extinction. The Asian origin of alvarezsauroids is also bolstered by the discovery of alvarezsaurid specimens from the Turonian-age Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan and Bannykus, Tugulusaurus, and Xiyunykus from the Early Cretaceous of China.[6][7]

Hand morphology

The differences in the morphology of the hand of basic Alvarezsauroidea and the derived members are characterized by digit reduction. In the evolution of theropod dinosaurs, modifications of the hand were typical. The digital reduction, for instance, is a striking evolutionary phenomenon that is clearly exemplified in theropod dinosaurs.[1] The enlargement of the manual digit II in alvarezsauroids and the concurrent reduction of the lateral digits, created one functional medial digit and two very small, and presumably vestigial, lateral digits. These morphological changes have been interpreted as adaptations for digging. One possible interpretation suggests that the alvarezsauroids feed on insects, using their hand to search beyond the tree bark. This interpretation is consistent with their long, elongate snout and small teeth. Another interpretation suggests that they used their claws to break into ant and termite colonies. But the arm anatomy of an alvarezsaurid would require the animal to lie on its chest against a termite nest.[4] In contrast to the digit reduction of the hand of derived alvarezsauroid to a claw used for digging, Haplocheirus was still able to grab things. However, Haplocheirus already shows the enlargement of the second manual digit. Important data on the evolution of the alvarezsauroid hand is also provided by the basal parvicursorine Linhenykus.[3] Another difference between Alvarezsauridae and Haplocheirus is the dentition. While alvarezsauroids show a simplified homogenous dentition, Haplocheirus on the other side possesses recurved serrated teeth. The dentition of Haplocheirus and their basal phylogenetic position, suggest that carnivory was the primitive condition for the clade.[1] Furthermore, Haplocheirus possesses more teeth on the maxilla than other alvarezsauroids.

References

- Choiniere, J.N., Xu, X., Clark, J.M., Forster, C.A., Guo, Y. and Han, F. (2010). "A basal alvarezsauroid theropod from the early Late Jurassic of Xinjiang, China." Science, 327: 571-574. doi:10.1126/science.1182143 PMID 20110503

- Hutchinson, Chiappe (1998). "The first known alvarezsaurid (Theropoda: Aves) from North America". "Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology". 18(3): 447-450.

- Xu, X., Sullivan, C., Pittman, M., Choniere, J.N., Hone, D., Upchurch, P., Tan, Q., Xiao, D., Tan, L. and Han, F. (2011). "A monodactyl nonavian dinosaur and the complex evolution of the alvarezsauroid hand." PNAS, 108: no.6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011052108

- Holtz, R.T. (2007). "Ornithomimosaurs and Alvarezsaurs". Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- Xu, X., Upchurch, P., Ma, Q., Pittman, M., Choiniere, J., Sullivan, C., Hone, D.W.E., Tan, Q., Tan, L., Xiao, D., and Han, F., 2013. Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarezsauroid biogeography. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58 (1): 25–46.

- Averianov A, Sues H-D (2017) The oldest record of Alvarezsauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the Northern Hemisphere. PLoS ONE12(10): e0186254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186254

- Xing Xu; Jonah Choiniere; Qingwei Tan; Roger B.J. Benson; James Clark; Corwin Sullivan; Qi Zhao; Fenglu Han; Qingyu Ma; Yiming He; Shuo Wang; Hai Xing; Lin Tan (2018). "Two Early Cretaceous fossils document transitional stages in alvarezsaurian dinosaur evolution". Current Biology. Online edition. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.057.

Sources

- Nesbitt, S.J., Clarke, J.A., Turner, A.H., Norell, M.A. (2011): "A small alvarezsauroid from eastern Gobi Desert offers insight into evolutionary patterns in the Alvarezsauroidea". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31:1. 144-153.

- Turner, A.H., Nesbit, S.J., Norell, M.A. (2009): "A Large Alvarezsaurid from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates. Number: 3648.

- Bonaparte, J.F. (1991). "Los vertebrados fosiles de la formacion Rio Colorado, de la ciudad de Neuquen y Cercanias, Creatcio Superior, Argentina" Rev. Mus. Agent. Cienc. "Bernardino Rivadavia", Paleontol. 4:16-123.

- Choiniere, J. (2010). Guest Post: Haplocheirus, the Skillful One Dave Hone's Archosaur Musings, April 23, 2011