Condorraptor

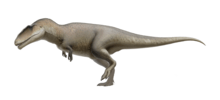

Condorraptor is a genus of megalosauroid theropod dinosaur. Its genus name means 'robber from Cerro Condor', referencing a nearby village, while its species name, currumili, is named after Hipolito Currumil, the landowner and discoverer of the locality. It was among the earliest large South American theropods, having been found in Middle Jurassic strata of the Cañadón Asfalto Formation in the Cañadón Asfalto Basin of Argentina. The type species, described in 2005, is Condorraptor currumili. It is based on a tibia, with an associated partial skeleton that may belong to the same individual. Initially described as a basal tetanuran,[1] Benson (2010) found it to be a piatnitzkysaurid megalosauroid and the sister taxon of Piatnitzkysaurus,[2] a finding supported by later studies.[3]

| Condorraptor | |

|---|---|

| |

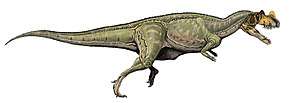

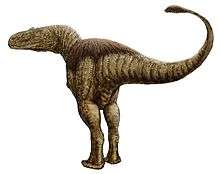

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Piatnitzkysauridae |

| Genus: | †Condorraptor Rauhut 2005 |

| Species: | †C. currumili |

| Binomial name | |

| †Condorraptor currumili Rauhut 2005 | |

Description

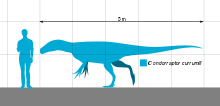

The holotype of Condorraptor is MPEF-PV 1672, a left tibia. Additional remains (MPEF-PV 1673 through 1697 and MPEF-PV 1700 through 1705) have also been referred to the species, including vertebrae, teeth, rib and chevron fragments, partial hip bones, femurs, a metatarsal IV, and a pedal phalanx. All of these remains were from the same locality of the holotype and likely represent the same individual. In 2007, various media outlets reported that an articulated skeleton of this species was discovered by a team led by Oliver Rauhut, but this find has not been described or referenced in literature.[4] Also in 2007, Rauhut described a fragmentary partial skull, MPEF 1717, from the Canadon Asfalto Formation. Due the skull's size, locality, tetanuran characteristics, and differences from the cranial material of Piatnitzkysaurus, it is possible that it belongs to Condorraptor.[5] The type specimen was a juvenile that was about 4.5 metres long and it weighted about 200 kg.[6] In 2016 Molina-Pérez and Larramendi estimated the probable adult specimen (MPEF 1717) at 8.5 meters and 1.65 tonnes.[7]

Condorraptor is notably similar to another theropod from the same formation, Piatnitzkysaurus. Unique among tetanurans, these two share a flat anterior surface of the anterior presacral centra.[2] However, it can be distinguished from Piatnitzkysaurus and other megalosauroids by several diagnostic features. Although some features considered diagnostic by the original description were later shown to be present in other megalosauroids, several features are still only known in Condorraptor. These include:[3]

- A pleurocoel in the anterior cervical vertebrae located immediately posterodorsal to the parapophysis.

- A shallow depression on the lateral surface of the tibia at the base of the cnemial crest.

- A metatarsal IV with a distinct dorsal step between the shaft and the distal articular facet.

In addition, Condorraptor differs from Piatnitzkysaurus by the shape of the underside of its sacral centra. In Condorraptor, the second centra has a broad and flat base while the third is gently concave. In Piatnitzkysaurus, the second centra's base is smoothly rounded while the third's is flat along its midline.[3]

Classification

The most basal clade within Megalosauroidea contains Condorraptor, Marshosaurus, Piatnitzkysaurus and Xuanhanosaurus. The next most basal clade comprises Chuandongocoelurus and Monolophosaurus. However, the affiliation of these clades with Megalosauroidea is poorly supported by tree support metrics, and it is possible that they will be classified outside of Megalosauroidea by future analyses.[2]

| Megalosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Rauhut, 2005. Osteology and relationships of a new theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Patagonia. Palaeontology. 48(1), 87-110.

- Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (4): 882–935. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00569.x.

- Carrano, Matthew T.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Sampson, Scott D. (2012-06-01). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. ISSN 1477-2019.

- Ryan, Michael J. 2007. New Condorraptor Unearthed. Palaeoblog. (reposting of news article)

- "A fragmentary theropod skull from the Middle Jurassic of Patagonia (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- Paul, G. S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, p. 89.

- Molina-Pérez and Larramendi (2016). "Molina-Pérez & Larramendi Appendix List" (PDF).