Mapusaurus

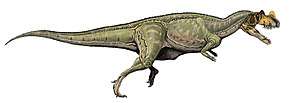

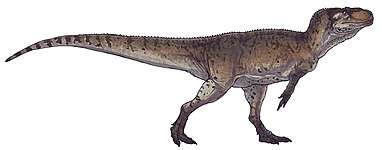

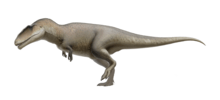

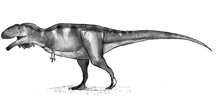

Mapusaurus ("Earth lizard") was a giant carnosaurian, carcharodontosaurid dinosaur from the early Late Cretaceous (late Cenomanian to early Turonian stage) of what is now Argentina and possibly Chile.

| Mapusaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeletons of an adult and a juvenile (left) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Carcharodontosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Carcharodontosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Giganotosaurini |

| Genus: | †Mapusaurus Coria & Currie, 2006 |

| Type species | |

| †Mapusaurus roseae Coria & Currie, 2006 | |

Discovery

Mapusaurus was excavated between 1997 and 2001, by the Argentinian-Canadian Dinosaur Project, from an exposure of the Huincul Formation (Rio Limay Subgroup, Cenomanian) at Cañadón del Gato. It was described and named by paleontologists Rodolfo Coria and Phil Currie in 2006.[1]

The name Mapusaurus is derived from the Mapuche word Mapu, meaning 'of the Land' or 'of the Earth' and the Greek sauros, meaning 'lizard'. The type species, Mapusaurus roseae, is named for both the rose-colored rocks, in which the fossils were found and for Rose Letwin, who sponsored the expeditions which recovered these fossils.

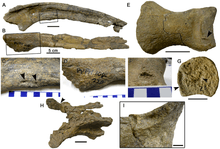

The designated holotype for the genus and type species, Mapusaurus roseae, is an isolated right nasal (MCF-PVPH-108.1, Museo Carmen Funes, Paleontología de Vertebrados, Plaza Huincul, Neuquén). Twelve paratypes have been designated, based on additional isolated skeletal elements. Taken together, the many individual elements recovered from the Mapusaurus bone bed represent most of the skeleton.[1]

Description

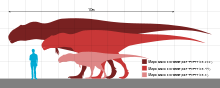

Mapusaurus was a large theropod and was roughly similar in size to its close relative Giganotosaurus, with the largest known individuals estimated as about 10.2 metres (33 ft) in length or more and weighing about 3 metric tons (3.3 short tons).[1] The longest individual for which Coria and Currie (2006) provided a concrete estimate in Table 1 (appendix lll) is the animal to which femur MCF-PVPH-208.203 belonged; this individual is estimated as 10.2 metres (33 ft) long.

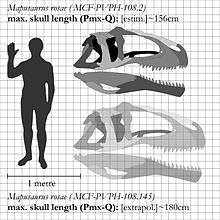

Coria and Currie note the presence of isolated bones from at least one longer individual, but do not provide a figure, instead finding the larger bones coherent with an individual of comparable size to Giganotosaurus holotype estimated at 12.2 metres (40 ft) in length,[1] although not with the same exact proportions, having taller and wider neural spines, a more elongate fibula (86 centimetres (34 in) compared to 83.5 centimetres (32.9 in)) but more slender (81-89% the width as in Giganotosaurus)[1] as well as a wider pubic shaft in minimal dimensions (10% wider as indicated by a 7.8 centimetres (3.1 in) long fragment catalogued as MCF-PVPH-108.145), and with a differently proportioned skull, shorter in length than Giganotosaurus because the maxilla is not elongated (12 teeth compared to 14 in Carcharodontosaurus), but deeper in proportion due to this, as well as narrower (due to the narrow nassals). Considering this, a fragmentary maxilla is coherent with the size of the Giganotosaurus-sized individual (MCF-PVPH-108.169). A neural arch from an axis (MCF-PVPH-108.83) and a scapular blade fragment are also the same exact size as the same elements in Giganotosaurus. The weight estimate of 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb) is from a 1,300 millimetres (51 in) long femur with a 455 millimetres (17.9 in) circumference (MCF-PVPH-208.234).[1]

Holtz estimated the maximum size of the animal at 12.6 metres (41 ft).[2] This estimate has been cited in Drew Eddy and Julia Clarke (2011),[3] and cited again in a phylogenetic table in a 2014 analysis by Canale et al.[4] Gregory Paul gave a lower estimation of 11.5 meters (37.7 ft) and 5 tonnes (5.5 short tons).[5] Other authors suggested that it measured 12.7 metres (42 ft) long and 7.6 metric tons (8.4 short tons) in weight.[6]

Coria and Currie diagnosed Mapusaurus as follows: "Mapusaurus n. gen. is a carcharodontosaurid theropod whose skull differs from Giganotosaurus in having thick, rugose unfused nasals that are narrower anterior to the nasal/maxilla/lacrimal junction; larger extension of the antorbital fossa onto maxilla; smaller maxillary fenestra; wider bar (interfenestral strut) between antorbital and maxillary fenestrae; lower, flatter lacrimal horn; transversely wider prefrontal in relation to lacrimal width; ventrolaterally curving lateral margin of the palpebral; shallow interdental plates; higher position of Meckelian canal; more posteriorly sloping anteroventral margin of dentary. Mapusaurus roseae is unique in that the upper quadratojugal process of jugal splits into two prongs; small anterior mylohyoid foramen positioned above dentary contact with splenial; second and third metacarpals fused; humerus with broad distal end and little separation between condyles; the brevis fossa of the ilium extends deeply into excavation dorsal to ischial peduncle. It also differs from Giganotosaurus in having conical, slightly curving cervical epipophyses that taper distally; axial posterior zygapohyses joined on midline; smaller and less elaborate prespinal lamina on midline of cervicals; remarkably sharp dorsal margin of cervical neural spines; tall, wider neural spines; curved ischiatic shaft; more slender fibula."[1]

Paleobiology

The fossil remains of Mapusaurus were discovered in a bone bed containing at least seven individuals of various growth stages.[4][3] Coria and Currie speculated that this may represent a long term, possibly coincidental accumulation of carcasses (some sort of predator trap) and may provide clues about Mapusaurus behavior.[1] Other known theropod bone beds include the Allosaurus-dominated Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry of Utah, an Albertosaurus bone bed from Alberta and a Daspletosaurus bone bed from Montana.

Paleontologist Rodolfo Coria, of the Museo Carmen Funes, contrary to his published article, repeated in a press-conference earlier suggestions that this congregation of fossil bones may indicate that Mapusaurus hunted in groups and worked together to take down large prey, such as the immense sauropod Argentinosaurus.[7] If so, this would be the first substantive evidence of gregarious behavior by large theropods other than Tyrannosaurus, although whether they might have hunted in organized packs (as wolves do) or simply attacked in a mob, is unknown. The authors interpreted the depositional environment of the Huincul Formation at the Cañadón del Gato locality as a freshwater paleochannel deposit, "laid down by an ephemeral or seasonal stream in a region with arid or semi-arid climate".[1] This bone bed is especially interesting, in light of the overall scarcity of fossilized bone within the Huincul Formation. An ontogenetic study by Canale et al (2014)[4] found that Mapusaurus displayed heterochrony, an evolutionary condition in which the animals may retain an ancestral characteristic during one stage of their life, but lose it as they develop. In Mapusaurus, the maxillary fenestrae are present in younger individuals, but gradually disappear as they mature.

Classification

Cladistic analysis carried out by Coria and Currie definitively showed that Mapusaurus is nested within the clade Carcharodontosauridae. The authors noted that the structure of the femur suggests a closer relationship with Giganotosaurus than either taxon shares with Carcharodontosaurus. They created a new monophyletic taxon based on this relationship, the subfamily Giganotosaurinae, defined as all carcharodontosaurids closer to Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus than to Carcharodontosaurus. They tentatively included the genus Tyrannotitan in this new subfamily, pending publication of more detailed descriptions of the known specimens of that form.[1]

The following cladogram after Novas et al., 2013, shows the placement of Mapusaurus within Carcharodontosauridae.[8]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

As previously mentioned, the Huincul Formation is thought to represent an arid environment with ephemeral or seasonal streams. The age of this formation is estimated at 97 to 93.5 Mya.[2] The dinosaur record is considered sparse here. Mapusaurus shared its environment with sauropods Argentinosaurus (one of the largest sauropods, if not the largest), and Cathartesaura. Abelisauroid theropods Skorpiovenator and Ilokelesia also lived in the region.[9]

References

- Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. ISSN 1280-9659. CiteSeerx: 10.1.1.624.2450 – via ResearchGate.

- Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF). Genus List.

- Eddy, Drew R.; Clarke, Julia A. (2011-03-21). "New Information on the Cranial Anatomy of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis and Its Implications for the Phylogeny of Allosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17932. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617932E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017932. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3061882. PMID 21445312.

- Canale, Juan Ignacio; Novas, Fernando Emilio; Salgado, Leonardo; Coria, Rodolfo Aníbal (2015-12-01). "Cranial ontogenetic variation in Mapusaurus roseae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the probable role of heterochrony in carcharodontosaurid evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 89 (4): 983–993. doi:10.1007/s12542-014-0251-3. ISSN 0031-0220.

- Paul, Gregory S (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 98.

- Molina-Pérez & Larramendi 2016. Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos, Larousse. Barcelona, Spain p. 262

- "Details Revealed About Huge Dinosaurs". ABC News US. Associated Press. 2006.

- Novas, Fernando E. (2013). "Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 45: 174–215. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.04.001.

- Sánchez, Maria Lidia; Heredia, Susana; Calvo, Jorge O. (2006). "Paleoambientes sedimentarios del Cretácico Superior de la Formación Plottier (Grupo Neuquén), Departamento Confluencia, Neuquén" [Sedimentary paleoenvironments in the Upper Cretaceous Plottier Formation (Neuquen Group), Confluencia, Neuquén]. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 61 (1): 3–18 – via ResearchGate.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Mapusaurus |

- Meat-Eating Dinosaur Was Bigger Than T. Rex. National Geographic News.

- "What were the longest/heaviest predatory dinosaurs?". Mike Taylor. The Dinosaur FAQ. August 27, 2002. (Named as Unnamed Argentinian Carcharodontosaurine)

- "[And the Largest Theropod is... http://dml.cmnh.org/2003Jul/msg00355.html]". The Dinosaur Mailing List Archives. Retrieved 21 March 2010 (Named as Undescribed Carcharodontosaurine)