Human mouth

In human anatomy, the mouth is the first portion of the alimentary canal that receives food and produces saliva.[1] The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane epithelium lining the inside of the mouth.

| Mouth | |

|---|---|

Head and neck | |

Photograph of the inside of an open human mouth. One palatine tonsil is also visible (white). | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os, cavitas oralis |

| MeSH | D009055 |

| TA | A01.1.00.010 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

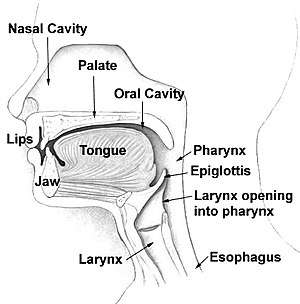

In addition to its primary role as the beginning of the digestive system, in humans the mouth also plays a significant role in communication. While primary aspects of the voice are produced in the throat, the tongue, lips, and jaw are also needed to produce the range of sounds included in human language.

The mouth consists of two regions, the vestibule and the oral cavity proper. The mouth, normally moist, is lined with a mucous membrane, and contains the teeth. The lips mark the transition from mucous membrane to skin, which covers most of the body.

Structure

Oral cavity

The mouth consists of 2 regions: the vestibule and the oral cavity proper. The vestibule is the area between the teeth, lips and cheeks.[2] The oral cavity is bounded at the sides and in front by the alveolar process (containing the teeth) and at the back by the isthmus of the fauces. Its roof is formed by hard palate at the front, and a soft palate at the back. The uvula projects downwards from the middle of the soft palate at its back. The floor is formed by the mylohyoid muscles and is occupied mainly by the tongue. A mucous membrane – the oral mucosa, lines the sides and under surface of the tongue to the gums, lining the inner aspect of the jaw (mandible). It receives the secretions from the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

Orifice

While shut, the orifice of the mouth forms a line between the upper and lower lip. In facial expression, this mouth line is iconically shaped like an up-open parabola in a smile, and like a down-open parabola in a frown. A down-turned mouth means a mouth line forming a down-turned parabola, and when permanent can be normal. Also, a down-turned mouth can be part of the presentation of Prader-Willi syndrome.[3]

Nerve supply

The teeth and the periodontium (i.e. the tissues that support the teeth) are innervated by the maxillary and mandibular divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Maxillary (upper) teeth and their associated periodontal ligament are innervated by the superior alveolar nerves, branches of the maxillary division, termed the posterior superior alveolar nerve, anterior superior alveolar nerve, and the variably present middle superior alveolar nerve. These nerves form the superior dental plexus above the maxillary teeth. The mandibular (lower) teeth and their associated periodontal ligament are innervated by the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular division. This nerve runs inside the mandible, within the inferior alveolar canal below the mandibular teeth, giving off branches to all the lower teeth (inferior dental plexus).[4][5] The oral mucosa of the gingiva (gums) on the facial (labial) aspect of the maxillary incisors, canines and premolar teeth is innervated by the superior labial branches of the infraorbital nerve. The posterior superior alveolar nerve supplies the gingiva on the facial aspect of the maxillary molar teeth. The gingiva on the palatal aspect of the maxillary teeth is innervated by the greater palatine nerve apart from in the incisor region, where it is the nasopalatine nerve (long sphenopalatine nerve). The gingiva of the lingual aspect of the mandibular teeth is innervated by the sublingual nerve, a branch of the lingual nerve. The gingiva on the facial aspect of the mandibular incisors and canines is innervated by the mental nerve, the continuation of the inferior alveolar nerve emerging from the mental foramen. The gingiva of the buccal (cheek) aspect of the mandibular molar teeth is innervated by the buccal nerve (long buccal nerve).[6]

Development

The philtrum is the vertical groves in the upper lip, formed where the nasomedial and maxillary processes meet during embryo development. When these processes fail to fuse fully, either a hare lip or cleft palate, (or both) can result.

The nasolabial folds are the deep creases of tissue that extend from the nose to the sides of the mouth. One of the first signs of age on the human face is the increase in prominence of the nasolabial folds.

Function

The mouth plays an important role in eating, drinking, and speaking. Mouth breathing refers to the act of breathing through the mouth (as a temporary backup system) if there is an obstruction to breathing through the nose, which is the designated breathing organ for the human body.[7]

Infants are born with a sucking reflex, by which they instinctively know to suck for nourishment using their lips and jaw. The mouth also helps in chewing and biting food.

For some disabled people, especially many disabled artists, who through illness, accident or congenital disability have lost dexterity, their mouths take the place of their hands, when typing, texting, writing, making drawings, paintings and other works of art by maneuvering brushes and other tools, in addition to the basic oral functions. Mouth painters hold the brush in their mouth or between their teeth and maneuver it with their tongue and cheek muscles, but mouth painting can be strenuous for neck and jaw muscles since the head has to perform the same back and forth movement as a hand does when painting.[8][9]

A male mouth can hold, on average, 71.2 ml, while a female mouth holds 55.4 ml.[10]

See also

- Head and neck anatomy

- Mouth breathing

- Index of oral health and dental articles

- List of basic dentistry topics

Further reading

- Nestor, James (2020). Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. Riverhead Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-0735213616.

References

- Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- Pocock, Gillian (2006). Human Physiology (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- Cassidy, Suzanne B.; Dykens, Elisabeth; Williams, Charles A. (2000). "Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: Sister imprinted disorders". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 97 (2): 136–46. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(200022)97:2<136::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 11180221.

- Susan Standring (editor in chief) (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). [Edinburgh]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0443066849.

- Lindhe, Jan; Lang, Niklaus P; Karring, Thorkild, eds. (2008) [2003]. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry 5th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard. p. 48. ISBN 9781405160995.

- Lindhe, Jan; Lang, Niklaus P; Karring, Thorkild, eds. (2008) [2003]. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry 5th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard. ISBN 9781405160995.

- Turowski, Jason (2016-04-29). "Should You Breathe Through Your Mouth or Your Nose?". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- "Squeezable Paint Brushes (Howard University)". www.aac-rerc.psu.edu. Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America. 31 May 2014.

- Winchester, Levi (10 July 2014). "Watch: Woman born without fully-formed limbs creates stunning artwork using her mouth". www.express.co.uk. Daily Express.

- Nascimento WV1, Cassiani RA, Dantas RO., 2012, "Gender effect on oral volume capacity", Dysphagia, 27(3):384-9.

External links