Will Durant

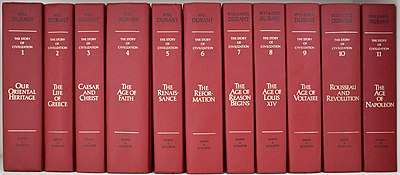

William James Durant (/dəˈrænt/; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work The Story of Civilization, 11 volumes written in collaboration with his wife, Ariel Durant, and published between 1935 and 1975. He was earlier noted for The Story of Philosophy (1926), described as "a groundbreaking work that helped to popularize philosophy".[1]

William Durant | |

|---|---|

William and Ariel Durant (1930) | |

| Born | William James Durant November 5, 1885 North Adams, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 7, 1981 (aged 96) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Historian, writer, philosopher, teacher |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Saint Peter's College (B.A., 1907) Columbia University (PhD, philosophy, 1917) |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Subject | History, philosophy, religion |

| Literary movement | Philosophy, etc. |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

He conceived of philosophy as total perspective or seeing things sub specie totius (i.e. “from the perspective of the whole”)—a phrase inspired by Spinoza's sub specie aeternitatis, roughly meaning "from the perspective of the eternal".[2] He sought to unify and humanize the great body of historical knowledge, which had grown voluminous and become fragmented into esoteric specialties, and to vitalize it for contemporary application.[3]

The Durants were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1968 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977.

Early life

Durant was born in North Adams, Massachusetts, to French-Canadian Catholic parents Joseph Durant and Mary Allard, who had been part of the Quebec emigration to the United States.[4][5]

After graduating from St. Peter's Preparatory School in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1903, Durant enrolled at Saint Peter's College (now University) also in Jersey City.[6] Historian Joan Rubin writes of that period, "Despite some adolescent flirtations, he began preparing for the vocation that promised to realize his mother's fondest hopes for him: the priesthood. In that way, one might argue, he embarked on a course that, while distant from Yale's or Columbia's apprenticeships in gentility, offered equivalent cultural authority within his own milieu."[7]

In 1905, he began experimenting with socialist philosophy, but, after World War I, he began recognizing that a "lust for power" underlay all forms of political behavior.[7] However, even before the war, "other aspects of his sensibility had competed with his radical leanings," notes Rubin. She adds that "the most concrete of those was a persistent penchant for philosophy. With his energy invested in Baruch Spinoza, he made little room for the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. From then on, writes Rubin, "his retention of a model of selfhood predicated on discipline made him unsympathetic to anarchist injunctions to 'be yourself.'... To be one's 'deliberate self,' he explained, meant to 'rise above' the impulse to 'become the slaves of our passions' and instead to act with 'courageous devotion' to a moral cause."[7] Durant graduated from Saint Peter's College in 1907.[6]

Teaching career

From 1907 to 1911, Durant taught Latin and French at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey.[5]

After leaving Seton Hall, Durant was a teacher at Ferrer Modern School from 1911 to 1913.[5] Ferrer was "an experiment in libertarian education," according to Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners.[5] Alden Freeman, a supporter of the Ferrer Modern School, sponsored him for a tour of Europe.[8] At the Modern School, he fell in love with and married a 15-year-old pupil, Chaya (Ida) Kaufman, whom he later nicknamed "Ariel". The Durants had one daughter, Ethel, and a "foster" son, Louis, whose mother was Flora -- Ariel's sister.

By 1914, he began to reject "intimations of human evil", notes Rubin, and to "retreat from radical social change." She summarizes the changes in his overall philosophy:

Instead of tying human progress to the rise of the proletariat, he made it the inevitable outcome of the laughter of young children or the endurance of his parents' marriage. As Ariel later summarized it, he had concocted, by his mid-30s, "that sentimental, idealizing blend of love, philosophy, Christianity, and socialism which dominated his spiritual chemistry" the rest of his life. The attributes ultimately propelled him away from radicalism as a substitute faith and from teaching young anarchists as an alternative vocation. Instead, late in 1913 he embarked on a different pursuit: the dissemination of culture.[7]

In 1913, he resigned his post as teacher and married Ariel Kaufman; they would have two children, Ethel and Louis.[5] To support themselves, he began lecturing in a Presbyterian church for $5 and $10; the material for the lectures became the starting point for The Story of Civilization.

Durant was director and lecturer at the Labor Temple School in New York City from 1914 to 1927 while pursuing a Ph.D. at Columbia University that he completed in 1917, the year he also served as an instructor in philosophy.[5]

Writing career

In 1908, Durant worked as a reporter for Arthur Brisbane's New York Evening Journal.[5] At the Evening Journal, he wrote several articles on sexual criminals.

In 1917, while working on a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia University, he wrote his first book, Philosophy and the Social Problem. He discussed the idea that philosophy had not grown because it avoided the actual problems of society. He received his doctorate that same year from Columbia.[9] He was also an instructor at the university.

The Story of Philosophy

The Story of Philosophy originated as a series of Little Blue Books (educational pamphlets aimed at workers) and was so popular it was republished in 1926 by Simon & Schuster as a hardcover book[10] and became a bestseller, giving the Durants the financial independence that would allow them to travel the world several times and spend four decades writing The Story of Civilization. Will left teaching and began work on the 11-volume Story of Civilization.

The Story of Civilization

The Durants strove throughout The Story of Civilization to create what they called "integral history." They opposed it to the "specialization" of history, an anticipatory rejection of what some have called the "cult of the expert." Their goal was to write a "biography" of a civilization, in this case, the West, including not just the usual wars, politics and biography of greatness and villainy but also the culture, art, philosophy, religion, and the rise of mass communication. Much of The Story considers the living conditions of everyday people throughout the 2500 year period that their "story" of the West covers. They also bring an unabashedly moral framework to their accounts, constantly stressing the "dominance of strong over the weak, the clever over the simple." The Story of Civilization is the most successful historiographical series in history. It has been said that the series "put Simon & Schuster on the map" as a publishing house. In the 1990s, an unabridged audiobook production of all 11 volumes was produced by Books On Tape read by Alexander Adams (Grover Gardner).

For Rousseau and Revolution (1967), the 10th volume of The Story of Civilization, the Durants were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for literature. In 1977, it was followed by one of the two highest awards granted by the United States government to civilians, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded by Gerald Ford.

The first volume of The Story of Civilization series, called Our Oriental Heritage (1935), is divided into an introduction and three books. The introduction takes the reader through the different aspects of civilization (economical, political, moral and mental). Book One is dedicated to the civilizations of the Near East (Sumeria, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Judea and Persia). Book two is "India and Her Neighbors." Book three moves deeper into the east, where the Chinese Civilization flourishes and Japan starts to find its place in the world's political map.

Other works

On April 8, 1944, Durant was approached by two leaders of the Jewish and Christian faiths, Meyer David and Christian Richard about starting "a movement, to raise moral standards." He suggested instead that they start a movement against racial intolerance and outlined his ideas for a "Declaration of Interdependence". The movement for the declaration, Declaration of INTERdependence, Inc., was launched at a gala dinner at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on March 22, 1945, attended by over 400 people including Thomas Mann and Bette Davis.[11] The Declaration was read into the Congressional Record on October 1, 1945, by Ellis E. Patterson.[12][lower-alpha 1]

Throughout his career, Durant made several speeches, including "Persia in the History of Civilization", which was presented as an address before the Iran-America Society in Tehran, Iran, on April 21, 1948 and had been intended for inclusion in the Bulletin of the Asia Institute (formerly, Bulletin of the American Institute for Persian, then Iranian, Art and Archaeology), Vol. VII, no. 2, which never saw publication.[13]

Rousseau and Revolution was followed by a slender volume of observations called The Lessons of History, which was both a synopsis of the series as well as analysis.

Though Ariel and Will had intended to carry the work on The Story of Civilisation into the 20th century, at their now very advanced age they expected the 10th volume to be their last. However, they went on to publish a final volume, their 11th, The Age of Napoleon in 1975. They also left behind notes for a 12th volume, The Age of Darwin, and an outline for a 13th, The Age of Einstein, which would have taken The Story of Civilization to 1945.

Three posthumous works by Durant have been published in recent years, The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time (2002), Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age (2001), and Fallen Leaves (2014).

Final years

The Durants also shared an intense love for one another as explained in their Dual Autobiography. After Will entered the hospital, Ariel stopped eating, and died on October 25, 1981. Though their daughter, Ethel, and grandchildren strove to keep Ariel's death from the ailing Will, he learned of it on the evening news, and died two weeks later, at the age of 96, on November 7, 1981. Will was buried beside Ariel in Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, in Los Angeles.

Writing about Russia

In 1933, he published Tragedy of Russia: Impressions from a Brief Visit and soon afterward The Lesson of Russia. A few years after the books were published, social commentator Will Rogers had read them and described a symposium he had attended that included Durant as one of the contributors. He later wrote of Durant, "He is just about our best writer on Russia. He is the most fearless writer that has been there. He tells you just what it's like. He makes a mighty fine talk. One of the most interesting lecturers we have, and a fine fellow."[1]

Writing about India

In 1930, he published The Case for India while he was on a visit to India as part of collecting data for The Story of Civilization. He was so taken aback by the devastating poverty and starvation he saw as result of British imperial policy in India that he took time off from his stated goal and instead concentrated on his polemic fiercely advocating Indian independence. He wrote about medieval India, "The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within."[14]

Legacy

Durant fought for equal wages, women's suffrage and fairer working conditions for the American labor force. Durant not only wrote on many topics but also put his ideas into effect. Durant, it has been said widely, attempted to bring philosophy to the common man.

He was trying to improve understanding of viewpoints of human beings and to have others forgive foibles and human waywardness. He chided the comfortable insularity of what is now known as Eurocentrism by pointing out in Our Oriental Heritage that Europe was only "a jagged promontory of Asia". He complained of "the provincialism of our traditional histories which began with Greece and summed up Asia in a line" and said they showed "a possibly fatal error of perspective and intelligence".

On decline and rebuilding of civilizations

Much like Oswald Spengler, he saw the decline of a civilization as a culmination of strife between religion and secular intellectualism, thus toppling the precarious institutions of convention and morality:

Hence a certain tension between religion and society marks the higher stages of every civilization. Religion begins by offering magical aid to harassed and bewildered men; it culminates by giving to a people that unity of morals and belief which seems so favorable to statesmanship and art; it ends by fighting suicidally in the lost cause of the past. For as knowledge grows or alters continually, it clashes with mythology and theology, which change with geological leisureliness. Priestly control of arts and letters is then felt as a galling shackle or hateful barrier, and intellectual history takes on the character of a "conflict between science and religion." Institutions which were at first in the hands of the clergy, like law and punishment, education and morals, marriage and divorce, tend to escape from ecclesiastical control, and become secular, perhaps profane. The intellectual classes abandon the ancient theology and—after some hesitation—the moral code allied with it; literature and philosophy become anticlerical. The movement of liberation rises to an exuberant worship of reason, and falls to a paralyzing disillusionment with every dogma and every idea. Conduct, deprived of its religious supports, deteriorates into epicurean chaos; and life itself, shorn of consoling faith, becomes a burden alike to conscious poverty and to weary wealth. In the end a society and its religion tend to fall together, like body and soul, in a harmonious death. Meanwhile among the oppressed another myth arises, gives new form to human hope, new courage to human effort, and after centuries of chaos builds another civilization.[15]

More than twenty years after his death, a quote from Durant, "A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself within"[16] appeared as the opening graphic of Mel Gibson's 2006 film Apocalypto. Durant also served as the history consultant for Anthony Mann's 1964 film The Fall of the Roman Empire. The narration at the beginning and the end of the film is taken almost directly from Durant's work Caesar and Christ.[17]

On religion and evolution

In an article in 1927, he wrote his thoughts about reconciling religion and Darwinism:

As to harmonizing the theory of evolution with the Biblical account of creation, I do not believe it can be done, and I do not see why it should be. The story of Genesis is beautiful, and profoundly significant as symbolism: there is no good reason to torture it into conformity with modern theory.[18]

In 1967 Durant wrote:

You will not need to be told, now, that I am a theological skeptic, believing in neither the warlike God of the Hebrews, nor the punishing and rewarding God of the Christians. I see many evidences of order in the universe, but also many conditions that seem to be disorderly, as in the reckless whimsies of meteors, or the arrogant deviations of planetary orbits from the paths that our geometry would have required.[19]

On history and Bible

In Our Oriental Heritage, Durant wrote:

The discoveries here summarized have restored considerable credit to those chapters of Genesis that record the early traditions of the Jews. In its outlines, and barring supernatural incidents, the story of the Jews as unfolded in the Old Testament has stood the test of criticism and archeology; every year adds corroboration from documents, monuments, or excavations.... We must accept the Biblical account provisionally until it is disproved.[20]

Selected books

See a full bibliography at Will Durant Online[21]

- 1917: Philosophy and the Social Problem New York: Macmillan.

- 1924: A Guide to Spinoza [Little Blue Book, No. 520]. Girard, KA: Haldeman-Julius Company.

- 1926: The Story of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1927: Transition. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1929: The Mansions of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster. Later with slight revisions re-published as The Pleasures of Philosophy

- 1930: The Case for India. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1931: A Program for America: New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1931: Adventures in Genius. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1931: Great Men of Literature, taken from Adventures in Genius. New York: Garden City Publishing Co.

- 1933: The Tragedy of Russia: Impressions From a Brief Visit. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1936: The Foundations of Civilisation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1953: The Pleasures of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1968: (with Ariel Durant) The Lessons of History. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1970: (with Ariel Durant) Interpretations of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1977: (with Ariel Durant) A Dual Autobiography. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 2001: Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age. New York: Simon & Schuster. Actually copyrighted by John Little and the Estate of Will Durant.

- 2002: The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 2003: An Invitation to Philosophy: Essays and Talks on the Love of Wisdom. Promethean Press.

- 2008: Adventures in Philosophy. Promethean Press.

- 2014: Fallen Leaves. Simon & Schuster.

The Story of Civilization

- 1935: Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1939: The Life of Greece. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1944: Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1950: The Age of Faith. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1953: The Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1957: The Reformation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1961: (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Reason Begins. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1963: (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Louis XIV. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1965: (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Voltaire. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1967: (with Ariel Durant) Rousseau and Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 1975: (with Ariel Durant) The Age of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Notes

- Other sources say it was in 1949.[11]

References

- Rogers, Will (1966). Gragert, Steven K. (ed.). The Papers of Will Rogers. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 393. The details of this book appear to be wrong – see talk page

- Durant, Will. "What is Philosophy?". Archived from the original on December 28, 2010.

- Durant, Will (1935). Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster. p. vii.

- "Will Durant". Freedom From Religion Foundation. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. (1999). Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Phoenix: Oryx Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-57356-111-8. OCLC 750569323 – via Google Books.

- "The will to capture history". Hudson Reporter. November 4, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Rubin, Joan Shelley. The Making of Middlebrow Culture, University of North Carolina Press (1992).

- Durant, Will (1935). Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster. p. 1051.

- Norton, Dan (Spring 2011), "A Symphony of History: Will Durant's The Story of Civilization", The Objective Standard, 6 (1), 3rd paragraph, retrieved May 29, 2012.

- WUACC, archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- Interdependence, Will Durant Foundation, archived from the original on March 10, 2012.

- Declaration (PDF), Will Durant foundation, archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2011.

- Durant, Will. "Persia in the History of Civilization" (PDF). Addressing Iran-America Society. Mazda Publishers. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011.

- Will Durant. The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage. p. 459.

- The Story of Civilization, Vol. 1, p. 71. See also this article's Discussion page.

- "Epilogue—Why Rome fell", The Story of Civilization, 3 Caesar And Christ,

A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself within. The essential causes of Rome's decline lay in her people, her morals, her class struggle, her failing trade, her bureaucratic despotism, her stifling taxes, her consuming wars.

- Ward, Allen M. (2009). Winkler, Martin M. (ed.). History, Ancient and Modern, in The Fall of the Roman Empire. The Fall of the Roman Empire: Film and History. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 57.

- Durant, Will. Popular Science, October 1927.

- Durant, Will. "Fallen Leaves", Simon and Schuster, December 2014.

- Durant, Will. Our Oriental Heritage, 1963, MJF Books; p. 300 (footnote).

- "Bibliography". Archived from the original on February 10, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Will Durant. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Will Durant |

- The Will Durant Timeline Project

- The Pulitzer Prizes: 1968

- "Durant, Will and Durant, Ariel." Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service (Accessed May 14, 2005)

- Works by Will Durant at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Will Durant at Internet Archive

- Articles, Will Durant Foundation, archived from the original on May 17, 2011, preserved at the Internet Archive

- Will Durant's list of One Hundred Best Books for an Education

- Will Durant on IMDb

- Will Durant at Find a Grave