One-China policy

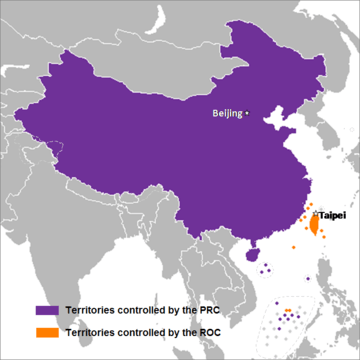

The "One-China policy" is a policy asserting that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, as opposed to the idea that there are two states, the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC), whose official names incorporate "China". Many states follow a one China policy, but the meanings are not the same. The PRC exclusively uses the term "One China Principle" in its official communications.[1][2]

| One-China policy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

One-China policy in practice

Countries recognizing PRC only

Countries recognizing PRC with informal ROC relations

Countries recognizing ROC only

| |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 一個中國政策 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 一个中国政策 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| One China principle | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 一個中國原則 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 一个中国原则 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Republic of China |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics |

|

|

The One China concept is different from the "One China principle", which is the principle that insists both Taiwan and mainland China are inalienable parts of a single "China".[3] A modified form of the "One China" principle known as the "1992 Consensus" is the current policy of the PRC government. Under this "consensus", both governments "agree" that there is only one sovereign state encompassing both mainland China and Taiwan, but disagree about which of the two governments is the legitimate government of this state. An analogous situation existed with West and East Germany in 1950–1970, North and South Korea, and more recently, the Syrian government and Syrian opposition.

The One-China principle faces opposition from supporters of the Taiwan independence movement, which pushes to establish the "Republic of Taiwan" and cultivate a separate identity apart from China called "Taiwanization". Taiwanization's influence on the government of the ROC implies the change of self-identity among Taiwan citizens: after the Communist Party of China expelled the ROC in the Chinese Civil War from most of Chinese territory in 1949 and founded the PRC, the ROC's Chinese Nationalist government, which still held Taiwan, continued to claim legitimacy as the government of all of China. Under former President Lee Teng-hui, additional articles were appended to the ROC constitution in 1991 so that it applied effectively only to the Taiwan Area prior to national unification.[4] However, former ROC president Ma Ying-jeou re-asserted claims on mainland China as late as 2008.[5]

Background

Before the early 1600s, Taiwan was inhabited mainly by Taiwanese aborigines, but the demographics began to change with successive waves of Han Chinese migration. Taiwan was first brought under the control of Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), a Ming-loyalist, in 1662 as the Kingdom of Tungning, before being incorporated by the Qing dynasty in 1683.

It was also ruled by the Dutch (1624–1662) and the Spanish (1626–1642, northern Taiwan only). The Japanese ruled Taiwan for half a century (1895–1945), while France briefly held sway over northern Taiwan in 1884–85.[6]

It was an outlying prefecture of Fujian Province under the Manchu Qing government of China from 1683 until 1887, when it was officially made a separate Fujian-Taiwan Province. Taiwan remained a province for eight years until it was ceded to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895.[7][8]

While Taiwan remained under Japanese control, the Qing dynasty was ousted and the First and Second Republic of China (ROC) were established from the Beiyang regime to the Kuomintang (KMT) from 1928.

Following the October 1945 Japanese surrender ceremonies in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan Province, Taiwan once again became the governing polity of China during the period of military occupation.[9][10][11][12] In 1949, after losing control of most of mainland China following the Chinese Civil War, and before the post-war peace treaties had come into effect, the ROC government under the KMT withdrew to occupied Taiwan. Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law. An argument has been made that Japan formally renounced all territorial rights to Taiwan in 1952 in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, but neither in that treaty nor in the peace treaty signed between Japan and China was the territorial sovereignty of Taiwan awarded to the Republic of China.[13][14] The treaties left the status of Taiwan—as ruled by the ROC or PRC—deliberately vague, and the question of legitimate sovereignty over China is why China was not included in the San Francisco Peace Treaty.[13][14] This argument is not accepted by those who view the sovereignty of Taiwan as having been legitimately returned to the Republic of China at the end of the war.[15] Some argue that the ROC is a government in exile,[16][17][18][19] while others maintain it is a rump state.[20]

The ROC government still governs Taiwan, but it transformed itself into a free and democratic state in the 1990s following decades of martial law.[21] During this period, the legal and political status of Taiwan has become more controversial, with more public expressions of Taiwan independence sentiments, which were formerly outlawed.

Viewpoints within Taiwan

Within Taiwan, there is a distinction between the positions of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

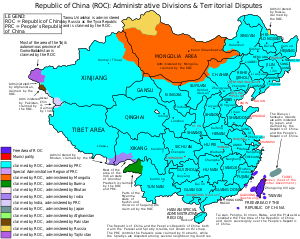

The Kuomintang holds the "One China Principle" and maintains its claim that under the ROC Constitution (passed by the Kuomintang government in 1947 in Nanjing) the ROC has sovereignty over most of China, including, by their interpretation, both mainland China and Taiwan. After the Communist Party of China expelled the ROC in the Chinese Civil War from most of Chinese territory in 1949 and founded the PRC, the ROC's Chinese Nationalist government, which still held Taiwan, continued to claim legitimacy as the government of all of China. Under former President Lee Teng-hui, additional articles were appended to the ROC constitution in 1991 so that it applied effectively only to the Taiwan Area.[22] The Kuomintang proclaims a modified form of the "One China" principle known as the "1992 Consensus". Under this "consensus", both governments "agree" that there is only one single sovereign state encompassing both mainland China and Taiwan, but disagree about which of the two governments is the legitimate government of this state. Former ROC President Ma Ying-jeou had re-asserted claims on mainland China as late as October 8, 2008.[23]

The Democratic Progressive Party does not agree with the "One China principle" as defined by the KMT or Two Chinas. Instead, it has a different interpretation, and believes "China" refers only to People's Republic of China and states that Taiwan and China are two separate countries, therefore there is One Country on Each Side and "one China, one Taiwan". The DPP's position is that the people of Taiwan have the right to self-determination without outside coercion.[24] Current president Tsai Ing-wen refuses to affirm the 1992 consensus.

The PRC's One-China principle faces opposition from supporters of the Taiwan independence movement, which pushes to establish the "Republic of Taiwan" and cultivate a separate identity apart from China called "Taiwanization".

Legal positions

Neither the ROC nor the PRC government recognizes the other as a legitimate national ruler.

People's Republic of China (PRC)

- Preamble of the Constitution:

Taiwan is part of the sacred territory of the People's Republic of China. It is the lofty duty of the entire Chinese people, including our compatriots in Taiwan, to accomplish the great task of reunifying the motherland.[25]

- Anti-Secession Law:

Article 2:

Article 5:

Republic of China (ROC)

- Article 4 of the Constitution (Effective 1948 to 2000):

"The territory of the Republic of China according to its existing national boundaries shall not be altered except by resolution of the National Assembly."

- Article 4 of the 6th Additional Articles of the Constitution (Effective 2000 to 2005):

"The territory of the Republic of China, defined by its existing national boundaries, shall not be altered unless initiated upon the proposal of one-fourth of all members of the Legislative Yuan, passed by three-fourths of the members of the Legislative Yuan present at a meeting requiring a quorum of three-fourths of all the members, and approved by three-fourths of the delegates to the National Assembly present at a meeting requiring a quorum of two-thirds of all the delegates."

- Article 4 of the 7th Additional Articles of the Constitution (Effective 2005 to present):

"The territory of the Republic of China, defined by its existing national boundaries, shall not be altered unless initiated upon the proposal of one-fourth of the total members of the Legislative Yuan, passed by at least three-fourths of the members present at a meeting attended by at least three-fourths of the total members of the Legislative Yuan, and sanctioned by electors in the free area of the Republic of China at a referendum held upon expiration of a six-month period of public announcement of the proposal, wherein the number of valid votes in favor exceeds one-half of the total number of electors."

In accordance with this legal position, legislation passed by the Legislative Yuan is signed by the President of the Republic of China. Only voters residing in the free area are eligible to vote and be elected in ROC elections.

Evolution of the policy

One interpretation, which was adopted during the Cold War, is that either the PRC or the ROC is the sole rightful government of all China and that the other government is illegitimate. While much of the western bloc maintained relations with the ROC until the 1970s under this policy, much of the eastern bloc maintained relations with the PRC. While the government of the ROC considered itself the remaining holdout of the legitimate government of a country overrun by what it thought of as Communist rebels, the PRC claimed to have succeeded the ROC in the Chinese Civil War. Though the ROC no longer portrays itself as the sole legitimate government of China, the position of the PRC remained unchanged until the early 2000s, when the PRC began to soften its position on this issue to promote Chinese reunification.

The revised position of the PRC was made clear in the Anti-Secession Law of 2005, which although stating that there is one China whose sovereignty is indivisible, does not explicitly identify this China with the PRC. Almost all PRC laws have a suffix "of the People's Republic of China" (prefix in Chinese grammar) in their official names, but the Anti-Secession Law is an exception. Beijing has made no major statements after 2004 which identify one China with the PRC and has shifted its definition of one China slightly to encompass a concept called the '1992 Consensus': both sides of the Taiwan strait recognize there is only one China—both mainland China and Taiwan belong to the same China but agree to differ on the definition of which China.

One interpretation of one China is that only one geographical region of China exists, which was split between two Chinese governments during the Chinese Civil War. This is largely the position of current supporters of Chinese reunification in Mainland China, who believe that "one China" should eventually reunite under a single government. Starting in 2005, this position has become close enough to the position of the PRC, allowing high-level dialogue between the Communist Party of China and the Pan-Blue Coalition of the ROC.

Policy position in the PRC

.jpg)

In practice, official sources and state-owned media never refer to the "ROC government", and seldom to the "government of Taiwan". Instead, the government in Taiwan is referred to as the "Taiwan authorities". The PRC does not accept or stamp Republic of China passports. Instead, a Taiwan resident visiting Mainland China must use a Taiwan Compatriot Entry Permit. Hong Kong grants visa free entry to holders of a Permit; while holders of a ROC passport must apply for a Pre-arrival Registration. Macau grants visa free entry to holders of both the permit and the passport.

Policy position in the ROC

.jpg)

The only official statement of the ROC on its interpretation of the One-China Principle dates back to 1 August 1992. At that time, the National Unification Council of the ROC expressed the ROC's interpretation of the principle as:[27]

- The two sides of the Strait have different opinions as to the meaning of "one China." To Beijing, "one China" means "the People's Republic of China (PRC)," with Taiwan to become a "Special Administrative Region" after unification. Taipei, on the other hand, considers "one China" to mean the Republic of China (ROC), founded in 1912 and with de jure sovereignty over all of China. The modern-day ROC, however, has jurisdiction only over Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu. Taiwan is part of China, and the Chinese mainland is part of China as well.

- Since 1949, China has been temporarily divided, and each side of the Taiwan Strait is administered by a separate political entity. This is an objective reality that no proposal for China's unification can overlook.

- In February 1991, the government of the Republic of China, resolutely seeking to establish consensus and start the process of unification, adopted the "Guidelines for National Unification". This was done to enhance the progress and well-being of the people, and the prosperity of the nation. The ROC government sincerely hopes that the mainland authorities will adopt a pragmatic attitude, set aside prejudices, and cooperate in contributing its wisdom and energies toward the building of a free, democratic and prosperous China.

However, political consensus and public opinion in Taiwan has evolved since 1992. There is significant difference between each faction's recognition for and understanding of the One China principle. The Pan-Blue Coalition parties, consisting of the Kuomintang, the People First Party, and the New Party, accept the One China principle. In particular, former President of the Republic of China, Ma Ying-jeou, stated in 2006 when he was the Kuomintang chairman that "One China is the Republic of China". Until the 1990s, the government actively stated that the ROC is the only legitimate "One China" while the PRC is illegitimate.

The Pan-Green Coalition parties, consisting of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Taiwan Solidarity Union, are more hostile to the policy, as they view Taiwan as a country separate from China. The former ROC President, Chen Shui-bian of the DPP, regards acceptance of the "One China" principle as capitulation to the PRC, and prefers to view it as nothing more than a topic for discussion, in opposition to the PRC's insistence that the "One China" principle is a prerequisite for any negotiation.

When the Republic of China established diplomatic relations with Kiribati in 2003 the ROC officially declared that Kiribati could continue to have diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. Despite the declaration, however, all countries maintaining official ties with Taipei continue to recognize the ROC as the sole legitimate government of China.[28]

The ROC does not recognize or stamp PRC passports. Instead, Chinese residents visiting Taiwan and other territory under ROC jurisdiction must use an Exit and Entry Permit issued by the ROC authorities.

Diplomatic relations

The One-China Principle is also a requirement for any political entity to establish diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. The PRC has traditionally attempted to get nations to recognize that "the Government of the People's Republic of China is the sole legal government of China ... and Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the People's Republic of China." However, many nations are unwilling to make this particular statement and there was often a protracted effort to find language regarding one China that is acceptable to both sides. Some countries use terms such as "respects", "acknowledge", "understand", "take note of", while others explicitly use the term "support" or "recognize" for Beijing's position on the status of Taiwan. This strategic ambiguity in the language used provides the basis for countries to have formal ties with People's Republic China and maintain unofficial ties to the Republic of China.

PRC government policy mandates that any country that wishes to establish diplomatic relationship with the PRC must first discontinue any formal relationship with the ROC. According to The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, "non-recognition of the Taiwanese government is a prerequisite for conducting formal diplomatic relations with the PRC —in effect forcing other governments to choose between Beijing and Taipei."[29][30] In order to compete for other countries' recognition, each Chinese government has given money to a certain few small countries. Both the PRC and ROC governments have accused each other of monetary diplomacy. Several small African and Caribbean countries have established and discontinued diplomatic relationships with both sides several times in exchange for huge financial support from each side.[31]

The name "Chinese Taipei" is used in some international arenas since "Taiwan" suggests that Taiwan is a separate country and "Republic of China" suggests that there are two Chinas, and thus both violate the One-China Principle. Taiwan could also be used as shorthand for the Customs Union between Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu. For example, in Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) Declaration on the March 2007 elections, issued on behalf of the European Union and with support of 37 countries, express mention is made of "Taiwan."

Most countries that recognize Beijing circumvent the diplomatic language by establishing "Trade Offices" that represent their interests on Taiwanese soil, while the ROC government represents its interests abroad with TECRO, Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office. The United States (and any other nation having diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China) does not have formal diplomatic relations with the ROC. Instead, external relations are handled via nominally private organizations such as the American Institute in Taiwan or the Canadian Trade Office in Taipei.

As for the Philippines, the unofficial Embassy is called the Manila Economic and Cultural Office. Though it is a cultural and economic office, the website explicitly says that it is the Philippine Representative Office in Taiwan. It also offers various consular services, such as granting visa and processing passport.

U.S. policy

In the case of the United States, the One-China Policy was first stated in the Shanghai Communiqué of 1972: "the United States acknowledges that Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States does not challenge that position." The United States has not expressed an explicitly immutable statement regarding whether it believes Taiwan is independent or not. Instead, Washington simply states that they understand the PRC's claims on Taiwan as its own. In fact, many scholars agree that U.S. One-China Policy was not intended to please the PRC government, but as a way for Washington to conduct international relations in the region, which Beijing fails to state. A more recent study suggests that this wording reflected the Nixon administration's desire to shift responsibility for resolving the dispute to the "people most directly involved" - that is, China and Taiwan. At the same time, the United States would avoid "prejudic[ing] the ultimate outcome" by refusing to explicitly support the claims of one side or the other.[32]

At the height of the Sino-Soviet split and Sino-Vietnamese conflict, and at the start of the reform and opening of the PRC, the United States strategically switched diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (ROC) to the People's Republic of China (PRC) on January 1, 1979.

When President Jimmy Carter in 1979 broke off relations with the ROC in order to establish relations with the PRC, Congress responded by passing the Taiwan Relations Act that maintained relations, but stopped short of full recognition of the ROC. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan also saw that the Six Assurances were adopted, the fifth being that the United States would not formally recognize Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan. Still, United States policy has remained ambiguous. In the House International Relations Committee on April 21, 2004, the Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, James A. Kelly, was asked by Rep. Grace Napolitano (D-CA) whether the United States government's commitment to Taiwan's democracy conflicted with the so-called One-China Policy. He admitted the difficulty of defining the U.S.'s position: "I didn’t really define it, and I’m not sure I very easily could define it." He added, "I can tell you what it is not. It is not the One-China principle that Beijing suggests."[33]

The position of the United States, as clarified in the China/Taiwan: Evolution of the "One China" Policy report of the Congressional Research Service (date: July 9, 2007) is summed up in five points:

- The United States did not explicitly state the sovereign status of Taiwan in the three US-PRC Joint Communiques of 1972, 1979, and 1982.

- The United States "acknowledged" the "One China" position of both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

- U.S. policy has not recognized the PRC's sovereignty over Taiwan;

- U.S. policy has not recognized Taiwan as a sovereign country; and

- U.S. policy has considered Taiwan's status as unsettled.

These positions remained unchanged in a 2013 report of the Congressional Research Service.[35]

On December 2, 2016, US President-elect Donald Trump and ROC President Tsai Ing-wen conducted a short phone call regarding "the close economic, political and security ties between Taiwan and the US".[36] On December 6, a few days after the call, Trump said that the US is not necessarily bound by its "one China" policy.[37][38][39]

On February 9, 2017, in a lengthy phone call, US President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping discussed numerous topics and President Trump agreed, at the request of President Xi, to honor the "one China" policy.[40]

U.S. public opinion on the One-China Policy

U.S. public opinion on the One-China Policy is much more ambiguous than the opinions of the American political elites and policy experts. A Pew Research poll from 2012 found that 84% of policy experts believed it to be very important to for the U.S. to build a strong relationship with China, whereas only 55% of the general public agreed with that statement.[41] This vast difference of agreement between policy experts and the American public is illustrated by Donald Trump's phone call 25 days after his inauguration to the President of Taiwan, breaking a decades-old policy that could be an expression of negative attitudes towards the People's Republic of China.[42]

Furthermore, U.S. populist attitudes towards the People's Republic of China are negative, where China is viewed as an economic adversary rather than a friendly rival. A 2015 Pew Research poll found that 60% of Americans view the loss of jobs to China as very serious, compared to only 21% who view the tensions between China and Taiwan as very serious.[43] Historical trends conducted by Gallup demonstrate an increase in perception among Americans that China is the leading economic power in the world today, with polls in 2000 showing only 10% agreeing with that statement and in 2016, 50% concurring with the statement.[44]

Cross-strait relations

The acknowledgment of the One China Principle is also a prerequisite by the People's Republic of China government for any cross-strait dialogue be held with groups from Taiwan. The PRC's One-China policy rejects formulas which call for "two Chinas" or "one China, one Taiwan"[45] and has stated that efforts to divide the sovereignty of China could be met with military force.

The PRC has explicitly stated that it is flexible about the meaning "one China", and that "one China" may not necessarily be synonymous with the PRC, and has offered to talk with parties on Taiwan and the government on Taiwan on the basis of the Consensus of 1992 which states that there is one China, but that there are different interpretations of that one China. For example, in Premier Zhu Rongji's statements prior to the 2000 Presidential Election in Taiwan, he stated that as long as any ruling power in Taiwan accepts the One China Principle, they can negotiate and discuss anything freely.

However, the One-China Principle would apparently require that Taiwan formally give up any possibility of Taiwanese independence, and would preclude any "one nation, two states" formula similar to ones used in German Ostpolitik or in Korean reunification. Chen Shui-bian, president of the Republic of China between 2000 and 2008 repeatedly rejected the demands to accept the One China Principle and instead called for talks to discuss One China itself. With the January and March 2008 elections in Taiwan, and the election of Ma Ying-jeou as the President of the ROC, who was inaugurated on May 20, a new era of better relations between both sides of the Taiwan Strait was established.[46] KMT officials visited Mainland China, and the Chinese ARATS met in Beijing with its Taiwanese counterpart, the Straits Exchange Foundation. Direct charter flights were therefore established.

One China was the formulation held by the ROC government before the 1990s, but it was asserted that the one China was the Republic of China rather than PRC. However, in 1991, President Lee Teng-hui indicated that he would not challenge the Communist authorities to rule mainland China. This is a significant point in the history of Cross-Strait relations in that a president of the ROC no longer claims administrative authority over mainland China. Henceforth, the Taiwan independence movement gained a political boost, and under Lee's administration the issue is no longer who rules mainland China, but who claims legitimacy over Taiwan and the surrounding islands. Over the course of the 1990s, President Lee appeared to drift away from the One-China formulation, leading many to believe that he was actually sympathetic to Taiwan independence. In 1999, Lee proposed a special state-to-state relations for mainland China–Taiwan relations which was received angrily by Beijing, which ended semi-official dialogue until June 2008, when ARATS and SEF met, and in which President Ma Ying-jeou reiterated the 1992 Consensus and the different interpretation on "One China".

After the election of Chen Shui-bian in 2000, the policy of the ROC government was to propose negotiations without preconditions. While Chen did not explicitly reject Lee's two states theory, he did not explicitly endorse it either. Throughout 2001, there were unsuccessful attempts to find an acceptable formula for both sides, such as agreeing to "abide by the 1992 consensus". Chen, after assuming the Democratic Progressive Party chairmanship in July 2002, moved to a somewhat less ambiguous policy, and stated in early August 2002 that "it is clear that both sides of the straits are separate countries". This statement was strongly criticized by opposition Pan-Blue Coalition parties on Taiwan, which support a One-China Principle, but oppose defining this "One China" as the PRC.

The One China policy became an issue during the 2004 ROC Presidential election. Chen Shui-bian abandoned his earlier ambiguity and publicly rejected the One-China Principle claiming it would imply that Taiwan is part of the PRC. His opponent Lien Chan publicly supported a policy of "one China, different interpretations", as done in 1992. At the end of the 2004 election, Lien Chan and his running mate, James Soong, later announced that they would not put ultimate unification as the goal for their cross-strait policy and would not exclude the possibility of an independent Taiwan in the future. In an interview with Time Asia bureau prior to the 2004 presidential elections, Chen used the model of Germany and the European Union as examples of how countries may come together, and the Soviet Union as illustrating how a country may fragment.

In March 2005, the PRC passed an Anti-Secession Law which authorized the use of force to prevent a "serious incident" that breaks the One China policy, but which at the same time did not identify one China with the People's Republic and offered to pursue political solutions. At the same session of the PRC Congress, a large increase in military spending was also passed, leading blue team members to interpret those measures as forcing the ROC to adhere to the One China Policy or else the PRC would attack.

In April and May 2005, Lien Chan and James Soong made separate trips to Mainland China,[47] during which both explicitly supported the Consensus of 1992 and the concept of one China and in which both explicitly stated their parties' opposition to Taiwan independence. Although President Chen at one point supported the trips of Lien and Soong for defusing cross-strait tensions,[48] he also attacked them for working with the "enemy" PRC. On April 28, 2008, Honorary Chairman Lien Chan of the then opposition Kuomintang visited Beijing and met with Hu Jintao for the fourth time since their historic encounter on April 29, 2005 in their respective capacity as party leaders of both the Chinese Communist Party and the KMT. Lien also met Chen Yunlin, director of the PRC's Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council.[49]

On May 28, 2008, Kuomintang Chairman Wu Po-hsiung made a landmark visit to Beijing,[50] and met and shook hands with the Communist General Secretary Hu Jintao, at the Great Hall of the People. He also visited the mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen. Hu Jintao called for resuming exchanges and talks, based on the 1992 Consensus, between mainland China's Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) and Taiwan's Strait Exchange Foundation (SEF), as early as possible, and practically solving problems concerning the two sides through talks on equal footing. Once the ARATS-SEF dialogue is resumed, priority should be given to issues including cross-Strait weekend chartered flights and approval for mainland China residents traveling to Taiwan, which are of the biggest concern to people on both sides of the Strait. "The KMT has won two important elections in Taiwan recently," Wu said, "which showed that the mainstream opinion of the Taiwan people identified with what the KMT stood for, and most of the Taiwan people agree that the two sides on the strait can achieve peaceful development and a win-win situation".[51] Wu also told reporters that he had stressed to Hu that Taiwan needed an international presence. "The Taiwanese people need a sense of security, respect and a place in the international community", Wu said. Hu was also quoted as having promised to discuss feasible measures for Taiwan to take part in international activities, particularly its participation in World Health Organization activities.[52]

See also

References

- "What is the 'One China' policy?". BBC News. 2017-02-10. Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- "The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2019-02-27. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- Assistant Secretary James Kelly, "The Taiwan Relations Act: The Next Twenty-Five Years," testimony before the Committee on International Relations, U.S. House of Representatives, April 21, 2004, p. 32, at http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/intlrel/hfa93229.000/hfa93229_0f.htm Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Lee Teng-hui 1999 interview with Deutsche Welle: https://fas.org/news/taiwan/1999/0709.htm Archived 2015-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ma refers to China as ROC territory in magazine interview". Taipei Times. 2008-10-08. Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan & co. OL 6931635M. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- Richard Bush: At Cross Purposes, US-Taiwan Relations since 1942. Published by M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, New York, 2004

- Alan M. Wachman: Why Taiwan? Geostrategic rationales for China's territorial integrity. Published by Stanford University Press Stanford, California 2007.

- UK Parliament, May 4, 1955, archived from the original on 2011-07-21, retrieved 2011-08-23

- Sino-Japanese Relations: Issues for U.S. Policy, Congressional Research Service, December 19, 2008, archived from the original on 2012-03-22, retrieved 2011-08-23

- Resolving Cross-Strait Relations Between China and Taiwan, American Journal of International Law, July 2000, archived from the original on 2011-07-21, retrieved 2011-08-23

- Foreign Relations of the United States, US Dept. of State, May 3, 1951, archived from the original on 2012-03-22, retrieved 2011-08-23

- Starr Memorandum of the Dept. of State, July 13, 1971, archived from the original on 2011-07-21, retrieved 2011-08-23

-

Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1963). Mandate for Change 1953–1956. Doubleday & Co., New York. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

The Japanese peace treaty of 1951 ended Japanese sovereignty over the islands but did not formally cede them to "China," either Communist or Nationalist.

- Tzu-Chin Huang. "Disputes over Taiwan Sovereignty and the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty Since World War II" (PDF). Institute of Modern History, Academia sinica. Central Academic Advisory Committee and Academic Affairs Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

Charles Holcombe (2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-521-51595-5. Archived from the original on 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

Richard J. Samuels (21 December 2005). Encyclopedia of United States National Security. SAGE Publications. p. 705. ISBN 978-1-4522-6535-3. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2020. - One-China Policy and Taiwan, Fordham International Law Journal, December 2004, archived from the original on 2012-03-22, retrieved 2011-08-23

-

Kerry Dumbaugh (Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division) (23 February 2006). "Taiwan's Political Status: Historical Background and Ongoing Implications" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2011-08-23.

While on October 1, 1949, in Beijing a victorious Mao proclaimed the creation of the People's Republic of China (PRC), Chiang Kai-shek re-established a temporary capital for his government in Taipei, Taiwan, declaring the ROC still to be the legitimate Chinese government-in-exile and vowing that he would "retake the mainland" and drive out communist forces.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

"Introduction to Sovereignty: A Case Study of Taiwan". Stanford University. 2004. Archived from the original on 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2011-08-23.

Enmeshed in a civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists for control of China, Chiang's government mostly ignored Taiwan until 1949, when the Communists won control of the mainland. That year, Chiang's Nationalists fled to Taiwan and established a government-in-exile.

- Republic of China government in exile, archived from the original on 2011-07-21, retrieved 2011-08-23

- Krasner, Stephen D. (2001). Problematic Sovereignty: Contested Rules and Political Possibilities. Columbia University Press. pp. 148.

For some time the Truman administration had been hoping to distance itself from the rump state on Taiwan and to establish at least a minimal relationship with the newly founded PRC.

- "Taiwan". 2019-01-30. Archived from the original on 2020-01-23. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- Lee Teng-hui 1999 interview with Deutsche Welle: https://fas.org/news/taiwan/1999/0709.htm Archived 2015-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ma refers to China as ROC territory in magazine interview". Taipei Times. 2008-10-08. Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- "DPP Party Convention". taiwandc.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "CONSTITUTION OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA". The People's Daily — Read 3rd paragraph, 10th line-. 1982-12-04. Archived from the original on 2010-08-12. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- "Anti-Secession Law". The People's Daily. 2005-03-14. Archived from the original on 2009-08-02. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- National Unification Council, Resolution of August 1, 1992 on the meaning of "one China" Archived 2009-03-01 at the Wayback Machine, 1 August 1992.

- "Exploring Chinese History :: Politics :: International Relations :: Nationalist Era Policy". ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- Erikson, Daniel P.; Chen, Janice (2007). "China, Taiwan, and the Battle for Latin America". The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs. 31 (2): 71.

- "The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue". China Internet Information Center. Archived from the original on 2019-02-27. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- "China and Taiwan in Africa". HiiDunia. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- Hilton, Brian (September 2018). "'Taiwan Expendable?' Reconsidered". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 25:3 (3): 296–322. doi:10.1163/18765610-02503004.

- "Secretary Powell Must Not Change U.S. Policy on Taiwan". heritage.org. Archived from the original on 2004-12-15. Retrieved 2005-01-16.

- "White House: no change to 'one China' policy after Trump call with Taiwan Archived 2017-06-02 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. 2 December 2016.

- Shirley A. Kan; Wayne M. Morrison (January 4, 2013). "U.S.-Taiwan Relationship: Overview of Policy Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-31. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- Metzler, John J. (7 December 2016). "Trump's Taiwan call: Tempest in a teapot?". www.atimes.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-13. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Trump says U.S. not necessarily bound by 'one China' policy". Reuters. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- "Donald Trump questions 'one China' policy". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-12. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "China official says Trump's Taiwan comments cause 'serious concern'". foxnews.com. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-12. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "Readout of the President's Call with President Xi Jinping of China". The White House. 9 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- "U.S. Public, Experts Differ on China Policies". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 2012-09-18. Archived from the original on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Bush, Richard (March 2017). "A One-China Policy Primer" (PDF). East Asia Policy Paper. 10: 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- "6 facts about how Americans and Chinese see each other". Pew Research Center. 2016-03-30. Archived from the original on 2017-11-06. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Inc., Gallup. "China". Gallup.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-03. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- "White Paper--The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue". Embassy of the PRC in the USA. 1993-08-06. Archived from the original on 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "Taiwan's new president makes immediate overtures to China". WSWS. 2008-06-04. Archived from the original on 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "People First Party leader visits China after KMT head's return". Taiwan Journal. 2005-05-13. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- Markus, Francis (2005-04-27). "Lien's China trip highlights tensions". BBC. Archived from the original on 2006-03-14. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "KMT's Lien to meet China's President Hu for fourth time". The China Post. 2008-04-27. Archived from the original on 2008-05-03. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "Kuomintang Chairman Wu Poh-hsiung arrives in Beijing". China Daily. 2008-05-27. Archived from the original on 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "KMT Returns to China". Lc Backer Blog. 2008-05-31. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- "China promises to resume cross-strait dialogue: KMT chief". Global Security. 2008-05-28. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

.svg.png)